• Parasomnias are defined as “undesirable physical events or experiences that occur during entry to sleep, within sleep, or during arousals from sleep.” • The indications for evaluation of patients with a suspected parasomnia with PSG include (1) potentially violent or injurious behavior, (2) behavior that is extremely disruptive to household members, (3) the parasomnia results in a complaint of excessive sleepiness, and (4) the parasomnia is associated with medical, psychiatric, or neurologic symptoms or findings. • If a PSG is indicated for evaluation of a patient for a suspected parasomnia, then use of video PSG (synchronized video and audio) with additional EEG electrodes is recommended. • The NREM parasomnias include confusional arousals (awakening with confusion), sleepwalking (ambulation during sleep), and sleep terrors (awakening with loud scream and intense fear). In children, NREM parasomnias occur out of stage N3 (first part of the night) but in adults can occur out of stages N1 or N2 during any part of the night. Approximately 60–70% of adults with a NREM parasomnia experienced one or more NREM parasomnias in childhood. • The REM parasomnias include the RBD, nightmare disorder, and recurrent sleep paralysis. • Diagnostic criteria for RBD include • REM sleep without atonia: the EMG finding of excessive amounts of sustained or intermittent elevation (transient muscle activity) of submental EMG tone or excessive phasic submental or (upper or lower) limb EMG twitching. • At least one of the following is present: • Sleep-related injurious, potentially injurious, or disruptive behavior by history. • Abnormal REM sleep behavior documented during PSG monitoring. • Absence of EEG epileptiform activity during REM sleep (unless RBD can be clearly distinguished from any concurrent REM sleep-related seizure disorder). • The sleep disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurologic disorder, mental disorder, or substance use disorder. • Treatments for RBD include environmental precautions, clonazepam, and/or melatonin (often in high doses). • The overlap parasomnia consists of manifestations of both an NREM parasomnia and RBD. • RBD has been associated with narcolepsy, Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy, multiple sclerosis, and certain medications. A significant proportion of patients with “idiopathic RBD” later develop Parkinson’s disease. • Nocturnal seizures may mimic parasomnias—especially frontal lobe epilepsy. Features favoring epilepsy over a parasomnia include stereotypical behavior (same manifestations each time) and more than one episode per night. • The sleep-related eating disorder is manifested by eating and drinking during the main sleep period and is associated with a variable degree of alertness and recall for the eating behavior. The behavior must be associated with one or more of several manifestations including eating peculiar food items, associated with insomnia due to sleep disturbance from the eating episodes, sleep-related injury, dangerous behaviors in pursuit of food, morning anorexia, or adverse consequences of binge eating. • Catathrenia is characterized by a deep inspiration and long expiratory groan, most commonly during REM sleep. • Secondary enuresis is defined as the onset of enuresis in a patient who has previously been dry for at least 6 months. The diagnosis of OSA should be considered in all children who snore and have secondary enuresis. • The exploding head syndrome is characterized by a sudden loud imagined noise or sense of violent explosion in the head occurring as the patient is falling asleep on waking during the night. The event is painless but patients usually awaken with fright. Determining a cause for abnormal movements or behavior during sleep is often a challenging problem for sleep physicians. A parasomnia is a motor, verbal, or experiential phenomenon that occurs in association with sleep (at sleep onset, during sleep, or after arousal from sleep) and is often undesirable. The term parasomnia comes from a combination of para from the Greek prefix meaning “alongside of” with the Latin word somnus meaning “sleep.” In the usual clinical setting, the term refers to undesirable events. In the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd edition (ICSD-2),1 parasomnias are defined as “undesirable physical events or experiences that occur during entry to sleep, within sleep, or during arousals from sleep.” Evaluation of nocturnal “spells or unusual behavior” begins with a detailed history of the nature, age of onset, and time of night of the episodes. Factors (sleep deprivation and medications) that may have affected the behaviors should be explored. A neurologic examination should be performed to rule out associated neurologic disorders. Not all parasomnias require evaluation by polysomnography (PSG). The indications for evaluation with PSG include2–4: (1) potentially violent or injurious behavior, (2) the behavior is extremely disruptive to household members, (3) the parasomnia results in a complaint of excessive sleepiness, and (4) the parasomnia is associated with medical, psychiatric, or neurologic symptoms or findings. The ICSD-2 lists a number of parasomnias (Box 28–1).1 Some parasomnias are associated with non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, some with REM sleep, and some are classified as “other parasomnias” because they can occur during either NREM or REM sleep or during wakefulness soon after arousal from sleep. The NREM parasomnias include (1) confusional arousals, (2) sleepwalking, and (3) sleep terrors.5–8 There is some overlap in these parasomnias and individual patients may manifest behavior consistent with all three types of NREM parasomnias on different nights. Although not listed in the major ICSD-2 diagnostic categories, sleep-related sexual behavior and sleep-related violence are considered variants of the confusional arousal–sleepwalking–sleep terrors spectrum. Confusional arousals usually occur from stage N3 in the first part of the night but can occur after an arousal from NREM sleep at any hour. In children, confusional arousals usually occur out of stage N3. In adults, confusional arousals may also occur out of stage N1 or stage N2.1,5 Amnesia for the event is common. Confusional arousal events are brief and, because of amnesia, often go unnoticed unless reported by the bed partner. During awakening, behavior may be inappropriate (especially forced awakening) and even violent. Although behaviors are usually simple (movements in bed, thrashing about, vocalization, or inconsolable crying), they can be more complex. There is frequently an overlap between confusional arousals and sleepwalking. In contrast to sleep terrors, patients with confusional arousals do NOT exhibit autonomic hyperactivity or signs of fear or emit a blood-curdling scream. The ICSD-2 lists two variants of confusional arousals1: 1. Severe morning sleep inertia (sleep drunkenness): This is a variant of confusional arousal in adults and arousal is often out of stage N2 or stage N1 sleep. 2. Sleep-related sexual behaviors: These include masturbation or sexual assault on adults or minors (sleep sex). This entity is described in more detail later in the “Sleepwalking (Somnambulism)” section. The EEG during arousal may show persistent delta activity, theta activity, or diffuse poorly reactive alpha activity. Increased chin EMG activity is typical and EMG artifact in the EEG derivations is common (Fig. 28–1). At event onset, the heart rate increases. The ICSD-2 diagnostic criteria for confusional arousals are listed in Box 28–2. Note that PSG findings are not part of the criteria. Most patients with confusional arousals will not require PSG unless the parasomnia has resulted in injury, the potential for injury, or if treatment is being considered. Sleepwalking is defined as a series of complex behaviors that are initiated during sleep (usually stage N3) and result in ambulation (Boxes 28–3 to 28–5). Activity can vary from simply sitting up in bed to walking. Patients usually are difficult to awaken during these episodes and, if awakened, are confused. Of interest, the eyes are usually open (wide open and “glassy-eyed”) during sleepwalking,1,3 but patients may be clumsy in their movements. Talking during sleep (somniloquy) can occur simultaneously. In children, sleepwalking usually occurs during the first third of the night, when stage N3 is present. However, studies in adults have recorded episodes beginning in stage N1 or N2 sleep and frequently in the second half of the night.5–8 Episodes of sleepwalking in children are rarely violent, and movements often are slow. In adults, sleepwalking episodes can be more complex, frenzied, violent, and longer in duration. Episodes of sleepwalking may be terminated by the patient returning to bed or simply lying down and continuing sleep out of bed. Patients are difficult to arouse during sleepwalking episodes. When aroused during sleepwalking, patients are typically very confused. In addition, there is total amnesia for the sleepwalking episodes (see Box 28–4). Sleepwalking can occur as soon as children can walk but peaks between the ages of 4 and 8 occurring in between 10% and 20% of children. The onset of sleepwalking can also occur in adulthood. However, most adult sleepwalkers had episodes during childhood (60–70% of adults with sleepwalking exhibited this parasomnia during childhood). Sleepwalking usually disappears in adolescence. One study of 100 patients with sleep-related injury found that 33% with sleepwalking had an age of onset after age 16, and 70% had episodes arising from both stages N1 and N2 as well as stage N3. The sleepwalking behaviors were variable in duration and intensity.6 A number of predisposing and precipitating factors for NREM parasomnias (including sleepwalking) have been identified in children and adults.1,8,9 There is a definite familial role in the development of sleepwalking (see Box 28–4). If one or both parents have a history of sleepwalking, the risk of a child developing sleepwalking episodes is greatly increased. Fever, sleep deprivation, and certain medications (e.g., zolpidem and other BZRAs, phenothiazines, TCAs, lithium) can precipitate the events. Sleepwalking during slow wave sleep rebound has been reported in a patient with OSA treated with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).10 Untreated sleep apnea can also be a predisposing factor, given the frequent arousals associated with respiratory events in this disorder. Effective treatment of sleep apnea can reduce the frequency of sleepwalking in some patients.11 The relationship between mental illness and adult NREM parasomnias is a topic of controversy.6,12 Some have suggested that persistence of sleepwalking into adulthood is a manifestation of underlying psychopathology. However, Schenck and coworkers6 found evidence of prior or current psychopathology in only about 48% of adults with sleepwalking/sleep terrors who underwent PSG monitoring for sleep-related injury. Therefore, the adult sleepwalking patients were equally as likely not to have psychopathology as to have this problem. In addition, there was typically no association between sleepwalking/sleep terrors and any concurrent psychopathology with respect to onset, clinical course, or treatment response.12 However, because mental illness and medication used to treat mental illness can disturb sleep, sleepwalking could well occur or re-emerge in patients with active mental illness. Although PSG is rarely performed to evaluate cases of sleepwalking, the classic finding is a sudden arousal occurring in stage N3 sleep (Fig. 28–2). During the prolonged arousal, there usually is tachycardia and often persistence of slow wave EEG activity—despite the presence of high-frequency EEG activity and an increase in EMG amplitude. Analysis of a large group of patients with sleepwalking and sleep terrors found that there was no prearousal buildup of delta activity, increase in heart rate, or prearousal increase in chin EMG. Postarousal, the EEG showed three patterns: (1) diffuse rhythmic (synchronized) delta activity, (2) diffuse delta and theta activity, and (3) prominent alpha and beta activity.13 The heart rate is often noted to increase at the onset of the event. Diagnostic criteria for sleepwalking are listed in Box 28–3 and do not require PSG findings. The ICSD-2 major criteria for a diagnosis of sleepwalking1 include (A) ambulation during sleep and (B) evidence of persistent sleep, altered consciousness, or impaired judgment during ambulation. Evidence for an altered state of consciousness includes difficulty in arousing the person, mental confusion when awakened from an episode, amnesia (complete or partial) for the episode, and abnormal behaviors. Abnormal behaviors include routine behaviors that occur at inappropriate times, inappropriate or nonsensical behaviors, and dangerous or potentially dangerous behaviors. The main complications of sleepwalking are social embarrassment and danger of self-injury or injury to others. Violent behavior (self-mutilation or homicide) and sexual assault (sleep sex) have been reported in association with sleepwalking episodes. Sleep-related sexual behavior or sex-somnia14,15 is a parasomnia in which sexual behavior occurs with limited awareness during the act, relative unresponsiveness to the external environment, and amnesia for the event. The behaviors range from sexual vocalizations to intercourse. These actions may include behaviors very atypical for the individual (e.g., anal intercourse). In contrast to typical sleepwalking, these events can exceed 30 minutes. Sleep-related violence occurs in a state consistent with sleepwalking/sleep terrors and is associated with an emotion of fear or anger. The violent behavior may be directed at individuals in close proximity or those who confront the individual during the parasomnia.16,17 The patient may either awaken or go back to sleep but typically has amnesia for the event. The violence is often atypical for the individual. Most cases of sleep-related violence occur in middle-aged men with a history of prior sleepwalking. Automatisms are defined as involuntary behavior over which an individual has no control. The behavior may be out of character and the individual may have no recall for the events. The sleep automatisms likely to result in injurious behavior include NREM parasomnias, sleep-related dissociative disorders (SRDDs; discussed in a later section), and sleep-related epilepsy. An important legal question for consideration is the presence or absence of criminal intent. When criminal action is taken against the violent sleepwalker, sleep medicine physicians may be called as expert witnesses.16,17 There are guidelines for expert witness qualifications and testimony.17 In addition, criteria have been proposed to assist in determination of the putative role of an underlying sleep disorder17 (Box 28–6). The treatment of sleepwalking includes environmental precautions (e.g., closed doors and windows, sleeping on the first level) and avoidance of precipitating causes such as sleep deprivation as well as reassurance. If the episodes are determined to require medication, benzodiazepines, TCAs, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may be tried. Clonazepam 0.5 to 2.0 mg qhs or temazepam 30 mg qhs are commonly prescribed. Medications should be given early enough before bedtime so that sleepwalking in the first slow wave cycle is prevented. In one study of patients with self-injurious behavior, bedtime clonazepam was successful in controlling sleep terrors/sleepwalking in greater than 80% of cases.6 However, not all studies have found clonazepam to be this effective. Another study of treatment of patients with sleepwalking found that those with any degree of sleep apnea had fewer sleepwalking episodes if sleep apnea was effectively treated.11 Conversely, treatment with benzodiazepines was NOT effective in those without sleep-related breathing problems.11 A recent systematic review of sleepwalking treatments found that no large controlled studies of treatment for sleepwalking have been reported.18 Sleep terrors, also called night terrors or pavor nocturnus, consist of sudden arousal, usually from stage N3 sleep, accompanied by a blood-curdling scream or cry and manifestations of severe fear (behavioral and autonomic) (Boxes 28–7 and 28–8). The affected individual typically is confused, diaphoretic, and tachycardic, and he or she frequently sits up in bed. It is difficult or impossible to communicate with a person having a sleep terror, and total amnesia for the event is usual. Patients may sleepwalk during episodes of sleep terrors. Thus, many consider sleepwalking and sleep terrors to be one syndrome with a spectrum of manifestations. Sleep terrors typically occur in prepubertal children (≤3%) and subside by adolescence; they are uncommon in adults. Sleep terrors rarely begin in adulthood. As noted previously, one study of patients with sleep terrors/sleepwalking evaluated for sleep-related injury found that 48% had evidence of current or prior psychopathology.6 However, adults with sleep terrors are just as likely not to have related psychopathology as to have this problem. In addition, sleep terrors/sleepwalking and any concurrent psychopathology are often not closely associated with respect to their onset, clinical course, or treatment response.12 Stress, febrile illness, sleep deprivation, and heavy caffeine intake have been identified as inciting agents for sleep terrors. Stressful events and sleep deprivation can sometimes precipitate re-emergence of problems that were present in childhood. Slow wave sleep rebound, such as occurs with nasal CPAP treatment of OSA, has also been associated with episodes of sleep terrors.19 The ICSD-2 criteria are listed in Box 28–7. The diagnostic criteria include an episode of terror usually initiated by a loud scream that is accompanied by autonomic nervous system activation and behavioral manifestations of intense fear. In addition, evidence of an altered state of consciousness including difficulty in arousing the person, mental confusion after awakening, and partial or complete amnesia for the event is required. The treatment of sleep terrors is similar to that for confusional arousal and sleepwalking. If the episodes of sleep terrors are infrequent, treatment beyond simple environmental precautions is unnecessary. The medications used for sleepwalking have also been used for sleep terrors. Benzodiazepines, TCAs, and SSRIs have been used with some success. No controlled study has evaluated treatments for sleep terrors.18 Avoidance of inciting agents is recommended (see Box 28–4). Comparison of characteristics of confusional arousal, sleep terrors, and sleepwalking are listed in Table 28–1. The differential diagnosis of these NREM parasomnias includes the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD), nightmare disorder, nocturnal seizure activity, the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and nocturnal panic attacks. Nightmare disorders (also called dream anxiety attacks) and RBD occur during REM sleep and are more common in the second part of the night. Body movements during RBD can result in patients leaving the bed but rarely the bedroom. RBD usually does not begin until after age 40 and has a strong male predominance. When patients are awakened from RBD episodes they are less confused than in NREM parasomnias. Differentiation of NREM parasomnias from partial complex seizures is difficult without complete EEG monitoring. Seizures tend to be more stereotypical and may occur during the day. Patients with nightmares, the PTSD, and RBD typically can relate complex dream mentation that promoted the event. In sleep-related panic attacks,20 the patient can awaken from NREM sleep following arousals and develop autonomic activation and fear. However, in contrast to the NREM parasomnias, patients with panic attacks do not have confusion, nonresponsiveness, amnesia, or dramatic motor activity. Panic attacks occur during wakefulness and tend to build in intensity over several minutes. TABLE 28–1 Comparison of the Characteristics of Non–Rapid Eye Movement Parasomnias Parasomnias usually associated with REM sleep (stage R) include RBD, recurrent isolated sleep paralysis, and nightmare disorders (see Box 28–1). RBD has two variants: overlap parasomnia and status dissociatus (SD). RBD is characterized by a loss of the normal muscle atonia associated with REM sleep with dream-enactment behavior (oneirism) that is often violent in nature (Box 28–9).6,21–24 Dreams are “acted out.” Limb and body movements often are violent (e.g., hitting a wall, kicking) and may be associated with emotionally charged utterances. The movements can be related to dream content (“kicking an attacker”), but the patient may or may not remember associated dream material when awakened during an episode. Serious injury to the patient or the bed partner can result from these episodes, which typically occur one to four times a week. Because the episodes occur during REM sleep, they are most common during the early morning hours (the second half of the night). There is a strong male predominance and most cases occur after age 50. The median age of onset is about 50 years, and a milder prodrome of sleep talking, simple limb-jerking, or vividly violent dreams may precede the full-blown syndrome. RBD can be idiopathic or associated with a number of neurodegenerative disorders and medications25–28 (Box 28–10). In animal experiments, lesions in areas of the pons (subcoeruleus in cat, sublateral dorsal nucleus in the rat) can result in body movements during REM sleep.25 As discussed in Chapter 24, descending pathways from atonia regions of the pons result in hyperpolarization and inhibition of spinal motor neurons (mediated by gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA] and glycine) during REM sleep. Damage to the atonia regions or the descending pathways can result in REM sleep without atonia. However, the precise anatomic changes and pathophysiology associated with REM without atonia in humans remain controversial. Furthermore, REM sleep without atonia is only one of the manifestations of RBD. Areas of the brain such as the limbic system are likely involved in the generation of violent dreams and the associated emotions. Either a disorder or release from inhibition of locomotor pattern generators must also be involved in RBD pathophysiology. The fact that RBD may be a harbinger of future development of disorders such as Parkinson’s disease24,25,27 has led some to hypothesize that dysfunction of areas of the brain such as the striatum may be associated with RBD. One study found reduced striatal dopamine transporters in patients with idiopathic RBD compared with normal controls.28 Of interest, Parkinson’s disease patients had the most severe reduction in striatal dopamine receptors consistent with the idea that RBD may represent an early manifestation of Parkinson’s disease in a significant number of patients. An acute form of RBD can occur after withdrawal from REM suppressants, such as ethanol. Even after extensive evaluation, about 60% of cases of chronic RBD are idiopathic (see Box 28–10). Causes of chronic RBD include multiple sclerosis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, dementia, ischemic cerebrovascular disease, and brainstem neoplasms.24–26 RBD can be associated with a number of neurologic disorders including narcolepsy and alpha synucleopathies including Parkinson’s disorder, Lewy body dementia, and multiple system atrophy.24,25 In one study, almost 40% of patients with idiopathic RBD later developed Parkinson’s syndrome, although the mean time from onset of RBD to onset of Parkinson’s disease was approximately 12 years.27 There is a strong male predominance in RBD. The acute onset of RBD in a middle-aged woman with other neurologic complaints should raise the possibility of multiple sclerosis. Drug-induced or drug-exacerbated cases of RBD have been reported (see Box 28–10) with the use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (e.g., phenelzine), TCAs (e.g., imipramine), SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine), selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine), and other antidepressants (mirtazapine).26 There can also be a sudden exacerbation of RBD when the dose of medications associated with RBD is increased. A group of patients with a history of dream-enactment behavior and daytime sleepiness was found to have OSA on PSG but no evidence of REM sleep without atonia.29 Treatment with CPAP eliminated the behaviors. It is possible that increased pressure for REM sleep (prior REM sleep fragmenation) overwhelms normal REM atonia processes in these cases. Of note, patients with both true RBD and OSA may also exhibit fewer RBD episodes when adequately treated with CPAP. Video PSG including both leg and arm EMG is recommended. A given PSG study may or may not reveal an episode of abnormal behavior/body movements, because most patients do not have nightly attacks. For this reason, some sleep centers perform multiple sleep studies if the diagnosis remains unclear. However, even if abnormal behavior is not documented by a given PSG, evidence of REM sleep without atonia (tonic or phasic EMG abnormality during REM sleep) is usually present. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) scoring manual30 provides criteria for scoring the EMG activity associated with RBD (Box 28–11). In the chin EMG, sustained muscle activity may be noted. Excessive phasic activity (TMA) may be noted in the chin EMG, limb EMGs (anterior tibial, extensor digitorum), or both (see Chapter 12). TMA in the leg EMG derivations can also be seen without evidence of sustained muscle activity in the chin EMG (Figs. 28–3 and 28–4).

Parasomnias

Nrem Parasomnias

Confusional Arousals

Variants of Confusional Arousals

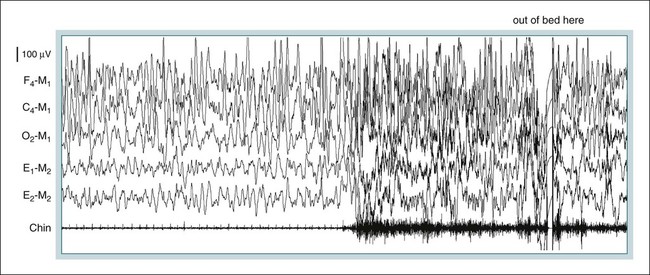

PSG Findings during Confusional Arousals

Diagnosis of Confusional Arousals

Sleepwalking (Somnambulism)

Epidemiology and Familial Pattern of Sleepwalking

Familial, Precipitating, and Predisposing Factors

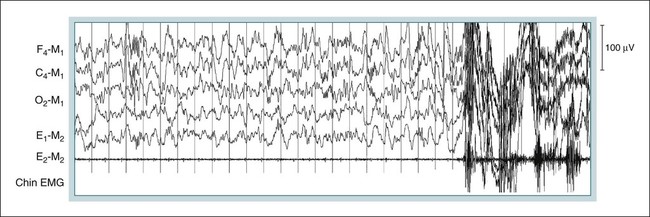

PSG in Sleepwalking

Diagnosis of Sleepwalking

Sleep-Related Sexual Behavior and Sleep-Related Violence

Sleep Disorders and the Law

Treatment of Sleepwalking

Sleep Terrors

Epidemiology

Precipitating and Predisposing Factors

Diagnosis of Sleep Terrors

Treatment of Sleep Terrors

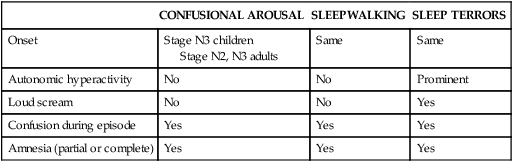

Differential Diagnosis of NREM Parasomnias

CONFUSIONAL AROUSAL

SLEEPWALKING

SLEEP TERRORS

Onset

Stage N3 children

Stage N2, N3 adults

Same

Same

Autonomic hyperactivity

No

No

Prominent

Loud scream

No

No

Yes

Confusion during episode

Yes

Yes

Yes

Amnesia (partial or complete)

Yes

Yes

Yes

Parasomnias Usually Associated With Rem Sleep (Stage R)

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD; Including Variants)

Epidemiology of RBD

Pathophysiology of RBD

Classifications and Causes of RBD

Pseudo-RBD

PSG in RBD