and Colin L. W. Driscoll2

(1)

Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

(2)

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Mayo Medical School, Rochester, MN, USA

Translabyrinthine Approach

Concept

Drill through the mastoid and semicircular canals to reach the posterior cranial fossa and internal auditory canal. The approach is anterior to the sigmoid sinus.

Conditions treated

Vestibular schwannomas

Other cranial nerve schwannomas within the posterior cranial fossa

Meningiomas within the posterior cranial fossa

Temporal bone tumors that involve the posterior fossa dura or have posterior fossa extension

Facial nerve decompression or repair in a non-hearing ear

Risks

Complete hearing loss in the operated ear and the potential for persistent tinnitus

Complete vestibular loss with disequilibrium that should improve with time, assuming there is normal vestibular function in the other ear and appropriate compensation occurs

Facial nerve injury

CSF leak

Necrosis or infection of the abdominal fat graft in the ensuing weeks after the surgery

Meningitis

Dysmetria if there is direct injury or vascular compromise to the cerebellar peduncle or brainstem

Benefits

This approach for resection of a vestibular schwannoma requires less brain retraction than the other approaches.

It provides a direct view of the entire course of the facial nerve.

The facial nerve is anterior to the vestibular schwannoma, making it less likely to be injured during drilling of the internal auditory canal or tumor removal as compared to the middle fossa approach.

Less headache, neck pain, and stiffness compared to the retrosigmoid approach

Additional notes

This approach is an excellent procedure for training residents and fellows in how to do mastoid and temporal bone surgery. However, it should be noted that the approach is not the key part of the procedure; tumor removal is. If too much time is spent appreciating the anatomy of the temporal bone during the approach, it may be late in the day when the careful and meticulous microdissection needed to remove the tumor is begun.

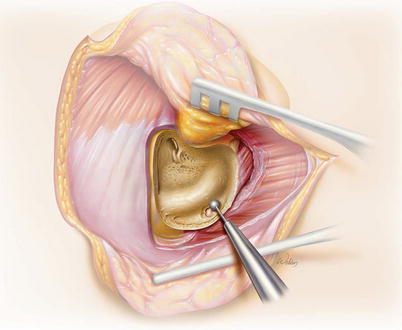

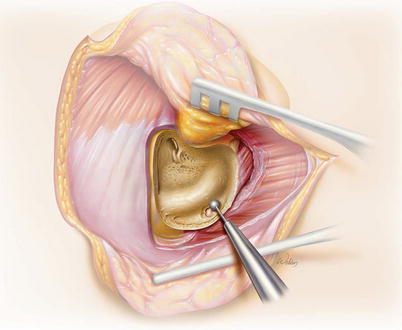

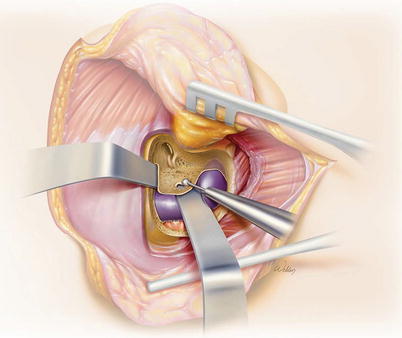

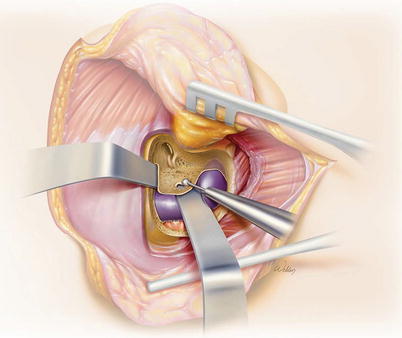

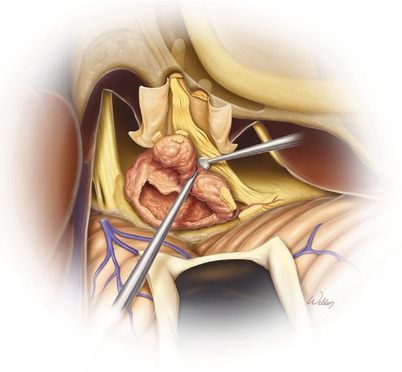

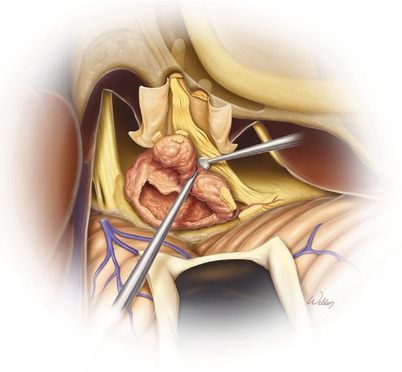

1.

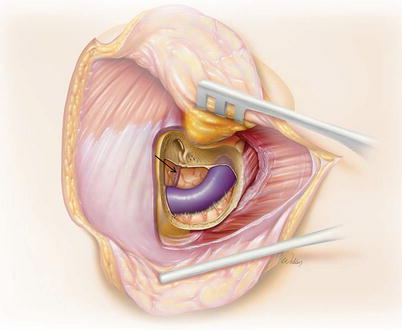

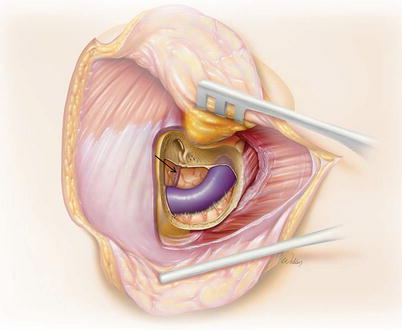

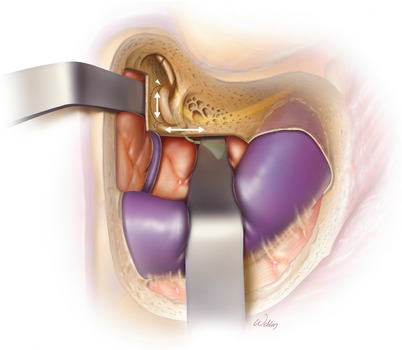

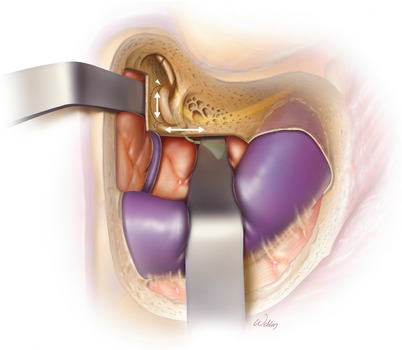

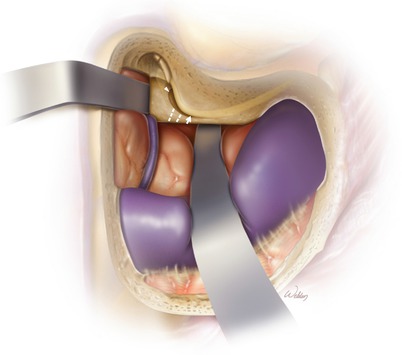

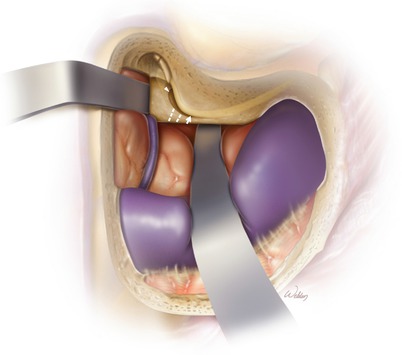

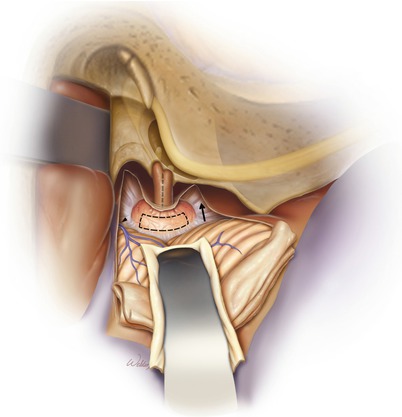

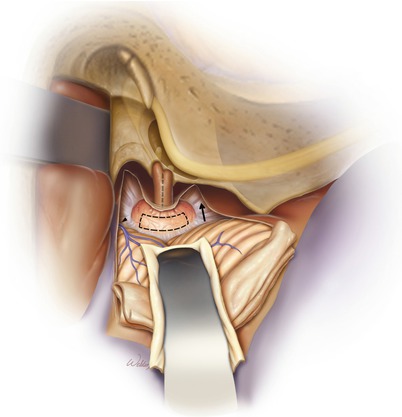

The concept of the translabyrinthine approach to access a vestibular schwannoma. Note that the opening in the skull is anterior to the sigmoid sinus. The cochlea is intact, but the semicircular canals have been removed. A malleable retractor is between the tumor and the cerebellar peduncle in this example. However, much of the surgery can be performed without the use of retraction. Retractors can create a more stable open field and allow visualization of the most medial tumor extent. Retractors may also be helpful when drilling to provide a solid barrier between the sigmoid sinus and dura to limit the risk of injury. However, retractors do not help with visualization of the lateral tumor, and in many patients with smaller tumors, no retraction is needed at all. Thus, retractors can be removed from the field when they are not necessary. This decreases the risk of retraction injury to the brain and thrombosis of the sigmoid sinus.

2.

Overview of the bone to be removed (gray).

3.

The incision is ~2–3 cm behind the postauricular sulcus. It is further back than what is typically used for otologic surgery to permit removal of enough bone for adequate visualization.

Although it is possible to use the same standard approach in all cases, there is value in considering each case individually and adapting your surgery to the particular challenges and opportunities presented. As a useful exercise, pause at the end of each operation and review the exposure and consider how it could be improved. Using a standard approach for all tumors will mean you are doing too much surgery for some tumors and you will also be less creative when you need to tackle the unusual tumors. For example, an intracanalicular tumor can be removed with a smaller incision and does not require decompression of the middle fossa dura or sacrifice of the emissary vein. These simple variations save time and decrease risk. There are several factors to consider when planning your approach. Tumor size and location are most important, but the course of sigmoid sinus, location and size of the jugular bulb, and scalp thickness (particularly in the posterior–inferior area) also can influence the plan. Be a thoughtful surgeon; have a reason for all you do.

4.

The mastoid cortex is exposed. It is unnecessary to dissect down the ear canal, and doing so simply increases the risk of creating a hole in the ear canal skin, which would connect the nonsterile ear canal to the sterile craniotomy wound. It is most efficient to create a full-thickness scalp flap with a single incision down to bone superiorly and posteriorly. As you extend inferiorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) is initially left attached to the bone and the scalp flap elevated to the anterior mastoid tip. The SCM is then taken down off the mastoid with cautery. For larger tumors, the digastric muscle is also taken out of its groove.

5.

A simple mastoidectomy is performed with identification of the sigmoid sinus, the tegmen, the mastoid antrum, and the lateral semicircular canal. Only the antrum should be opened. The aditus ad antrum will need to be sealed with fascia at the conclusion of the procedure to prevent CSF leak, and it is easier to do this when the opening is small.

Another option for this portion of the procedure is to remove the incus and open the superior part of the facial recess. This allows direct packing of the Eustachian tube orifice at the end of the procedure which may reduce the incidence of postoperative CSF leak.

6.

The retrosigmoid dura is identified and the overlying bone thinned with a large cutting burr. It is then “egg-shelled” into fragments with a large diamond burr. The bone fragments are then dissected off the dura with a Joseph or Freer elevator. Removing the bone allows the sigmoid sinus to be retracted posteriorly, permitting wider exposure. This is particularly critical for tumors >2 cm, but it is helpful for nearly all tumors.

During this process, the mastoid emissary vein is often sacrificed. Carefully decompressing this structure and coagulating with bipolar cautery at least a few millimeters from the sigmoid sinus will prevent getting a larger hole in the sidewall of the sinus. If the sigmoid sinus is more posterior or the tumor is small (so less retraction is anticipated to be necessary), the emissary vein can often be preserved.

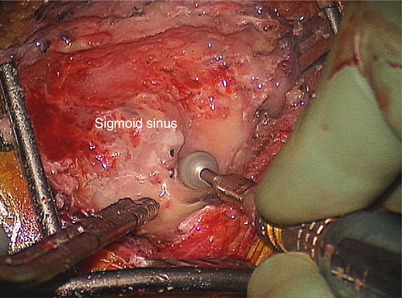

7.

The bone over the sigmoid sinus is then thinned and “egg-shelled” in a similar fashion. The bone fragments can be removed or loosened as necessary to reach the lip of bone anterior to the sigmoid sinus. It is easier and safer to remove smaller bone islands rather than one large piece. If the sinus tears while elevating a bone island, stop and leave that fragment in place. Prior to removing the bone over the sinus, it is important to have removed the retrosigmoid bone as shown in the previous illustration. This is because if the sinus is accidentally opened, it can be easily compressed with Surgicel and a cottonoid to control the bleeding.

Great care should be employed to avoid entering the sinus as this increases risk of thrombosis, venous congestion with the potential for increased intracranial pressure, and devastating venous infarction. It is most vulnerable as it turns medially toward the jugular bulb. If the sigmoid sinus is inadvertently entered, Surgicel and gelfoam can be placed, and gentle pressure with a cottonoid can be used to control the bleeding. This usually does not completely obstruct the blood flow within the sinus.

This is a part of the operation where it is important to mentally shift from an aggressive drilling mindset to a careful microdissection mode. Careful management of the sigmoid not only limits the risk of serious complications but also saves time and allows for more flexibility in retractor placement. Bleeding from the sinus is easily controlled but requires extra care in that area for the remainder of the case.

8.

Malleable retractors are then positioned between the posterior and middle cranial fossa dura and their bony plates. This bone can then be quickly removed with a rongeur or a drill down to the level of the labyrinth without risk of tearing the dura.

9.

After removal of the mastoid, the middle and posterior fossa dura are exposed. Bleeding from the superior petrosal sinus (arrow) can be managed with bipolar cautery. If cautery is ineffective, a piece of Surgicel can be inserted through the opening intraluminally both proximally and distally to plug the sinus. Elevating the sinus out of the bony groove will limit the risk of injuring the sinus.

10.

Next, identify the course of the vertical segment of the facial nerve just distal to the second genu. It should be left within its bony sheath but traced out inferiorly. This will allow safe exposure of the sigmoid sinus as it courses medially to the facial nerve and forms the jugular bulb. This maneuver is particularly helpful for tumors >2 cm in the cerebellopontine angle where a larger opening is needed to dissect the tumor off the cerebellum and the cerebellar peduncle.

The endolymphatic duct can be noted as a tether between the posterior face of the temporal bone and the posterior fossa dura (arrow). It should be transected with an 11 blade scalpel where it enters the bone. Once this is performed, the malleable retractor in the posterior fossa can be advanced all the way to the porus acusticus.

11.

The labyrinthectomy is performed by drilling parallel to the middle and posterior fossa dura (arrows). We typically do not trace out the canals during this process. Doing so expends time that could be better used later in the procedure when dissecting out the tumor. Care should be taken not to drill anterior to the ampullate ends of the lateral and superior semicircular canals (arrowhead) as the facial nerve might be damaged within the labyrinthine segment or geniculate ganglion.

The duct of the lateral semicircular canal is parallel to and directly superior to the horizontal segment of the facial nerve. By drilling through the lateral semicircular canal from superior to inferior, the facial nerve can be safely identified proximal to the second genu.

12.

The ampullated ends of the lateral and superior semicircular canals open into the anterior vestibule (arrowhead). The vestibule is directly medial to the horizontal facial nerve. A diamond bit is used to extend the opening of the vestibule posteriorly toward the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal (arrow). Note that the horizontal and vertical segments of the facial nerve should be traced out all the way from the anterior edge of the vestibule to the sigmoid sinus. A thin layer of bony fallopian canal should be left covering it for safety, but this exposure is critical to achieve ideal visualization of the cerebellar peduncle during tumor dissection.

Remember that the vestibular nerve innervates the utricle and saccule within the vestibule as well as the ampullae of the semicircular canals. Therefore, the vestibule marks the location of the fundus of the internal auditory canal. Completing the approach now requires finding the porus acusticus and tracing the internal auditory canal (dotted lines) out to the vestibule.

The porus acusticus is much deeper than the fundus. However, by simply drilling the temporal bone parallel to the posterior fossa dura as was done during the labyrinthectomy, you will eventually find it. Drilling through this bone can be frustrating because it is very dense. However, if you get concerned that you are not drilling in the proper location, you can also palpate within the intracranial space between the dura and the bone to find the porus acusticus. This will give you confidence that you are aiming in the proper direction and give you a clue about how much further you need to drill to get there.

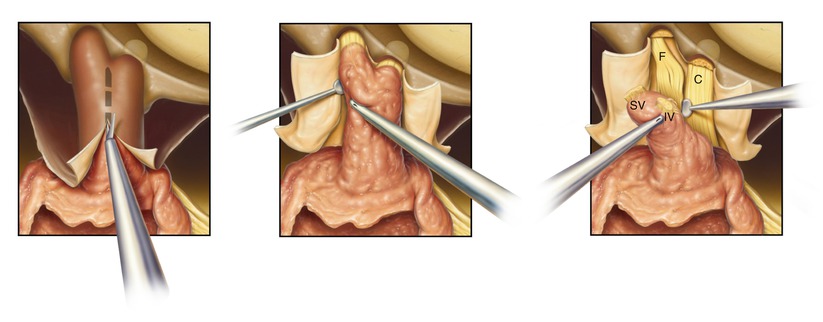

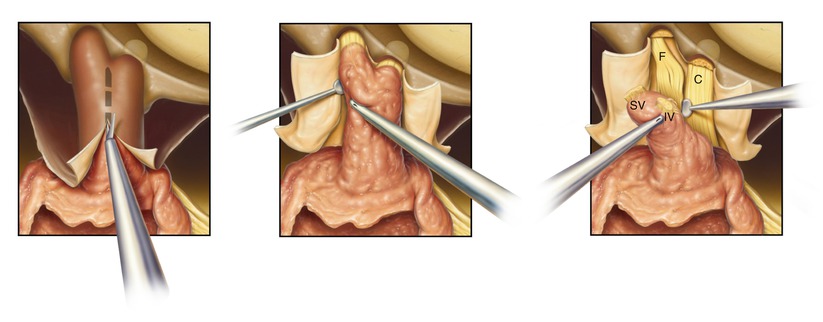

13.

Once the porus acusticus (PA) is identified, drill troughs superior and inferior to the internal auditory canal, and trace it out to the vestibule. Since the facial nerve may take a course over the superior aspect of the tumor, the dura absolutely needs to remain intact while drilling the superior trough. This is best achieved by leaving a thin layer of bone over the dura to protect its contents during drilling. This is perhaps not quite as critical when drilling the inferior trough, and a small dural tear is acceptable.

The cross-sections show the normal layout of the nerves of the internal auditory canal (lower inset) and what they look like with an inferior vestibular nerve tumor (IVT) present (upper inset). Facial nerve (F), cochlear nerve (C), superior vestibular nerve (SV), and inferior vestibular nerve (IV).

When drilling out laterally near the fundus, care should be taken near the labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve (arrow). This segment of the nerve is quite thin and not enveloped with a thick epineurial covering yet. Also, it is very close to the vestibule at the edge of the superior trough. Thus, the superior troughs can be drilled deeper medially but should be kept shallower laterally.

Initially, the bone is thinned all along the internal auditory canal, and then the remaining thin layer is removed around the edges of the dissection, and the cap of bone can be removed. It is safest to remove bone down to the dura inferiorly along the internal auditory canal first and then across the transverse crest and lastly along the superior internal auditory canal in the region of the facial nerve. The dissection of the bone can be blind around the superior internal auditory canal, but as it is thinned, the bone covering the internal auditory canal will become mobile. Thus, the last very thin eggshell can be fractured rather than drilled, offering more protection to the underlying facial nerve.

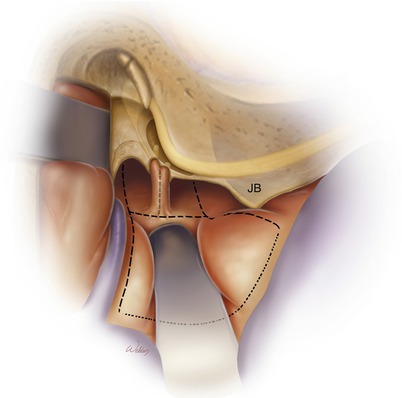

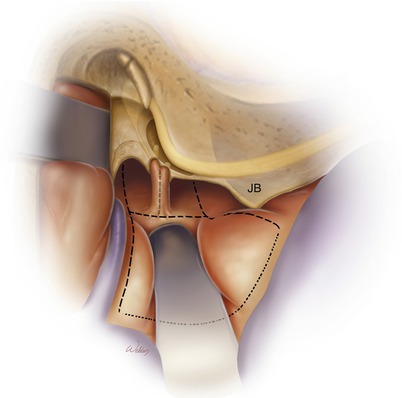

14.

Drill the troughs deeper to expose the dura anterior to the porus acusticus. Also, the jugular bulb (JB) should be skeletonized. The superior aspect of the JB is the inferior limit of drilling and easily identified. It is also critical to remove the bone along the posterior aspect of the JB to obtain adequate room to expose the tumor. At this point in the operation, there is a tendency to feel like you have removed enough bone and you want to get on with tumor removal. Removing a few more millimeters of bone deep in the troughs can pay big dividends later in the case when following the facial nerve. Tumors are centered on the internal auditory canal so half the tumor volume is anterior to the internal auditory canal. Having good exposure to this part of the tumor is important.

The dotted lines show the area of dural opening. The posterior limit is the sigmoid sinus, and the superior limit is the superior petrosal sinus. The square of dura between the sigmoid sinus and the internal auditory canal can be removed and discarded or left attached in the presigmoid area. While fancy dural flaps can be developed, in practicality it is impossible to close them in a watertight fashion at the end of the case, and it is not worth the effort.

15.

Initially, only the posterior fossa dura is opened. The dura of the internal auditory canal is not immediately opened because it helps to support the tumor during the dissection process, thereby reducing traction on the facial nerve.

A moist Telfa pledget is used between the malleable and the exposed cerebellum. This distributes the retraction pressure and minimizes trauma.

Cerebrospinal fluid can be released by gently opening the arachnoid membranes inferior to the tumor (arrow). We prefer to perform this maneuver using a blunt broad instrument, like a Penrose #2.

A bridging (or Dandy’s) vein (arrowhead), which drains blood from the cerebellum into the superior petrosal sinus, is often not in the way for smaller tumors and can be left alone. For larger tumors, more retraction of the cerebellum may be needed, and this vein will need to be divided. While there is significant collateral circulation in the cerebellum, venous infarction is an unpredictable and potentially devastating event, so veins should be preserved where possible.

The posterior face of the tumor is tested with the nerve stimulator to make sure the facial nerve is not draped across it. This would be highly unusual as the facial nerve is almost always anterior to the tumor, but it is critical to check. We use a high current or voltage for this maneuver as we expect the results to be negative. When we think we should be probing the facial nerve, we use a low-level stimulus to best identify the border of the nerve.

A window is then made in the tumor with a scalpel or scissors (dotted lines) and the core of the tumor debulked.

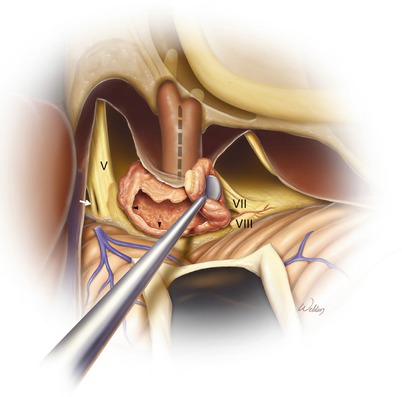

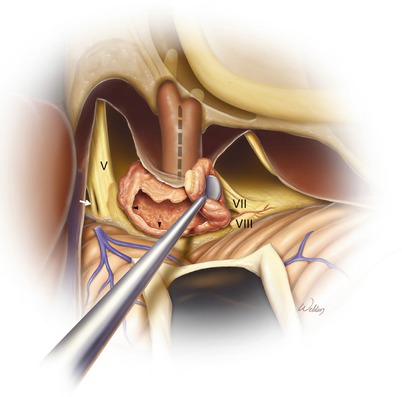

16.

After debulking, the tumor capsule can be microdissected off the surrounding tissues and collapsed inward. The capsule is removed in pieces during this process. The nerve stimulator should be used repeatedly during this process to verify that the facial nerve is not draped over the section of capsule to be removed.

An important goal is to dissect directly within the tumor–arachnoid interface. If one begins leaving arachnoid on the tumor, there are many more blood vessels to contend with, and the dissection plane is not obvious. If you get out of the correct plane, go back to a place where you are sure you are in the correct place and start again. This is why it is good to leave an edge of tumor visible when making a window (arrowheads)

The eighth cranial nerve is divided proximally to the tumor (VIII). Just deep to this is the root entry zone of the facial nerve (VII). It should be identified using the facial nerve stimulator before sectioning the eighth cranial nerve. Also, there is typically a small artery between the root entry zones of cranial nerve VII and VIII. This artery is a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery that feeds the brainstem. Every effort should be made to preserve all arteries.

Larger tumors often are adjacent to the trigeminal nerve (V). Most of the bulk of the trigeminal nerve is sensory, and only a small bundle consists of motor fibers (arrow). Thus, it should not be surprising to be unable to stimulate the fifth cranial nerve with the nerve stimulator until you move the probe superiorly to reach the motor division.

17.

After the majority of the tumor within the cerebellopontine angle has been debulked and the facial nerve has been identified at the brainstem, the internal auditory canal can be dissected.

Left panel: The dura of the internal auditory canal is opened after verifying with the nerve stimulator that the facial nerve is not directly underneath the planned incision. A microscissors or an angled sickle knife works well to make this opening.

Middle panel: The superior pole of the tumor is carefully separated from the internal auditory canal dura near the fundus until the facial nerve is identified. If the tumor has dilated the internal auditory canal and there is a lot of bulk, the posterior aspect of the tumor can be removed before doing this maneuver. This makes it easier to rotate the tumor and minimizes traction on the facial nerve.

Right panel: The superior vestibular nerve (SV) and inferior vestibular nerve (IV) are divided at the fundus (or simply teased out of the fundus) and the plane between the cochlear nerve (C) and the facial nerve (F) identified. If possible, the cochlear nerve is left in place to minimize dissection trauma to the facial nerve. If the cochlear nerve is infiltrated with tumor, it is also separated at the fundus and sharp dissection used to carefully separate the tumor from the facial nerve. Identifying the correct plane is critical, or tumor adherent to the facial nerve will be left behind.

It is beneficial to be flexible in how you go about removing the tumor. There should not be a sense of urgency when finding the facial nerve or other landmarks. All of the important structures will eventually be delineated. Each patient and tumor provides challenges and opportunities. Take advantage of what is most accessible and easy.

Do not dissect the internal auditory canal until the tumor in the cerebellopontine angle has been debulked to limit the risk of stretching the facial nerve. A significant debulking of the internal mass of the tumor with an ultrasonic aspirator (i.e., the CUSA) is extremely helpful as it allows for the capsule to be able to be teased away from the surrounding normal structures. It is preferable to retract tumor from nerves and blood vessels rather than push these structures off the tumor surface. When possible, force should be directed to the tumor and not the nerves. In general, less manipulation equates with less risk of injury and better function.

18.

As the tumor removal progresses and the dissection is carried down to the portion most adherent to the facial nerve along its course in the midcerebellopontine angle, it is easy to create too much traction on the nerve. The tumor remnant can be supported in the posterior fossa with gelfoam. Also, rather than working from either proximal or distal along the nerve, the tumor can be rolled inferiorly or superiorly and the facial nerve plane followed without pulling.

Also, this is the time of the operation that the decision to perform a total, near-total, or subtotal tumor removal is made. If the tumor is highly adherent to the facial nerve, it is typically better to leave a small and thin remnant attached to the facial nerve rather than to damage the facial nerve in a heroic attempt to remove all tumors. The remnant is unlikely to grow, and if it does, it can be treated with stereotactic radiotherapy. In contrast, aggressive dissection of the facial nerve is guaranteed to produce facial nerve weakness.

For smaller tumors, the cochlear nerve may be able to be preserved and thus offer the possibility of cochlear implantation (which should be considered for patients with NF II). For most tumors, over 1.5 cm becomes quite difficult to preserve a satisfactory cochlear nerve.

19.

To close the craniotomy, start by removing all Telfa strips and cottonoids. Counts must be correct. Surgicel on the sigmoid sinus can be left in place. The wound is irrigated, and any bleeding is controlled. If there are large air cells in the petrous apex, these should be occluded with bone wax to prevent CSF leak.

A piece of temporalis fascia or a dural substitute (like Duragen) is then laid over the aditus ad antrum. Tisseal can be used around it to obtain a watertight seal. Finally, two or three pieces of abdominal fat are placed into the defect to fill it. We typically dumbbell a little bit of fat through the defect in the posterior fossa dura to help plug it. Care is taken not to stretch the facial nerve when placing the fat and to not fill up the cerebellopontine angle with fat.

Another closure technique advocated by some surgeons (not shown) is to open the facial recess, separate the incudal–stapedial joint, remove the incus, and drill away the incudal buttress. The middle ear and Eustachian tube are then packed with an abdominal adipose graft at the time of closure. This works well and may reduce the risk of CSF leak.

If desired, a titanium or resorbable mesh plate can be placed over the fat graft to help keep the appropriate pressure. This also makes soft tissue closure easier and may result in improved cosmesis.

The wound is then closed in three layers (periosteum, subcutaneous tissues, and skin). A pressure dressing is applied for 1 day if the plate was used or 4 days if no plate was used.

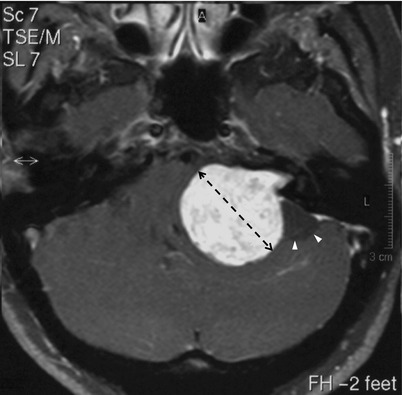

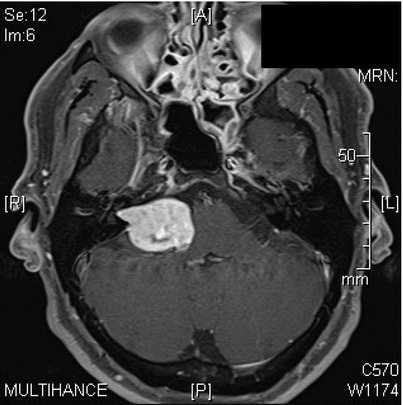

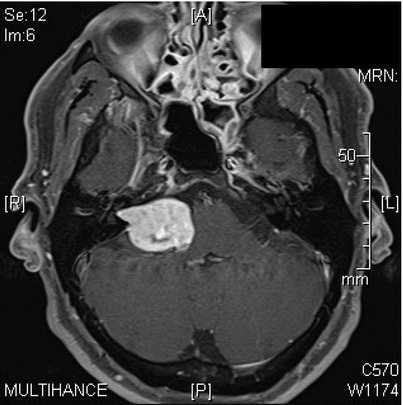

20.

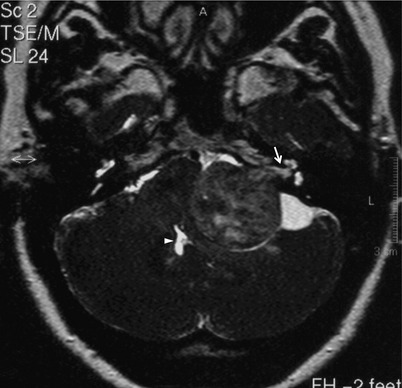

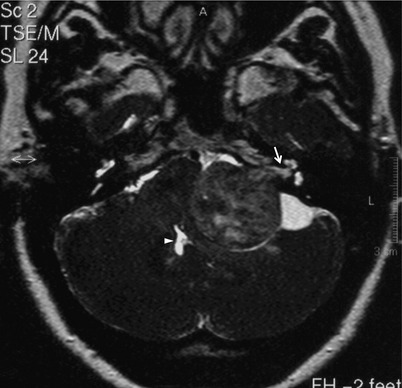

Case 1. Axial T1 MRI with gadolinium of a patient with a 3.4 cm left vestibular schwannoma. The dimension is taken from the largest dimension in the cerebellopontine angle, excluding the tumor within the internal auditory canal (arrow). There is significant compression of the brainstem, cerebellar peduncle, and cerebellum. A small arachnoid cyst is visible posterior to the tumor. This is not a cyst within the tumor because the margin between the cyst and the cerebellum does not enhance (arrowheads).

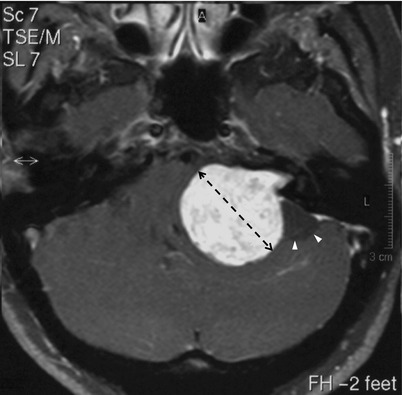

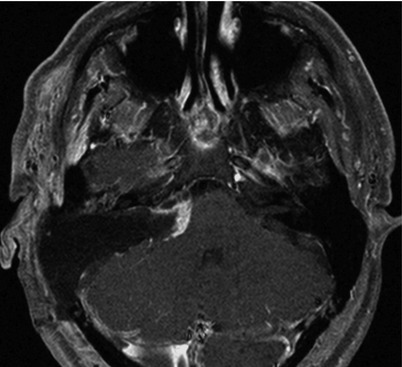

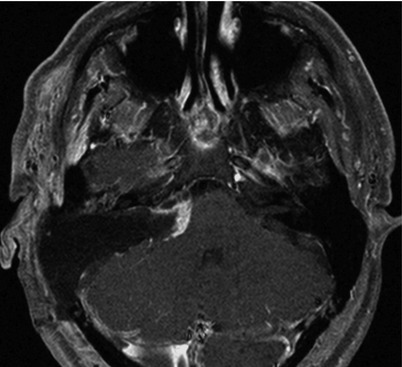

21.

Axial FIESTA T2-weighted image of the same tumor. The tumor is solid, and there is CSF within the arachnoid cyst. There is a slight amount of CSF between the distal end of the tumor and the fundus of the internal auditory canal (arrow). There is compression and distortion of the fourth ventricle, but it remains patent (arrowhead).

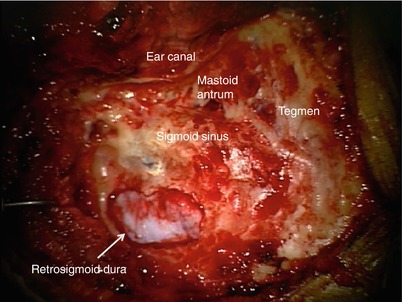

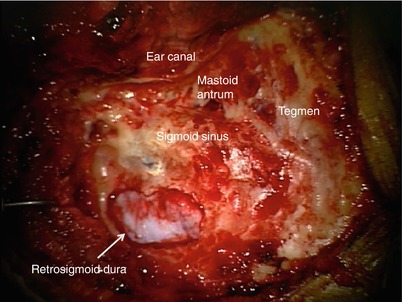

22.

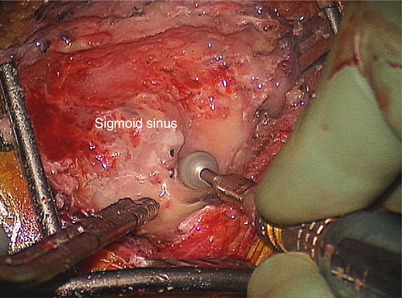

A translabyrinthine approach was used to remove the tumor. Here, we only demonstrate specific features of the bony drilling and tumor dissection process. A mastoidectomy was performed, the tegmen and sigmoid sinus were identified, and the retrosigmoid dura was exposed. The ear canal was left intact.

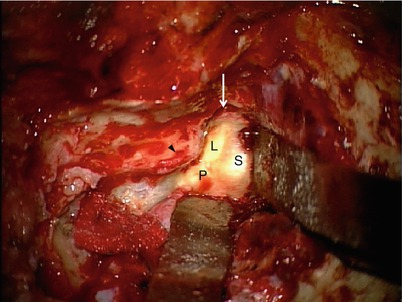

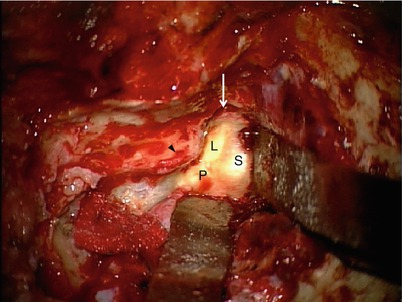

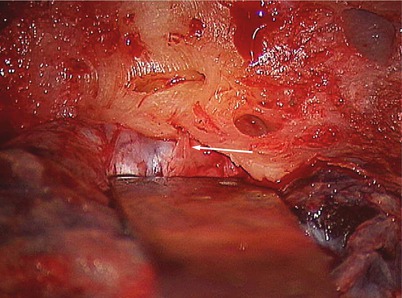

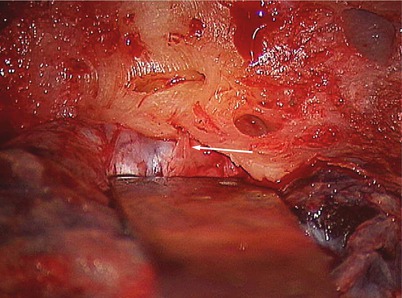

23.

The bone over the sigmoid sinus was thinned to allow the sinus to be compressed. The bone covering the presigmoid posterior fossa dura and the dura of the floor of the middle cranial fossa was removed. The lateral, posterior, and superior semicircular canals are within the dense otic capsule bone (L, P, S).

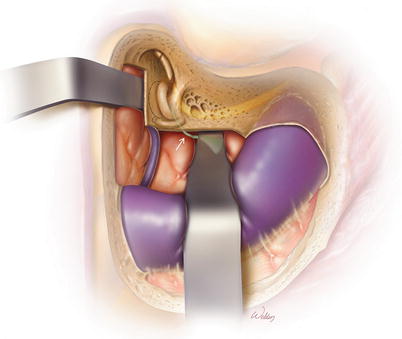

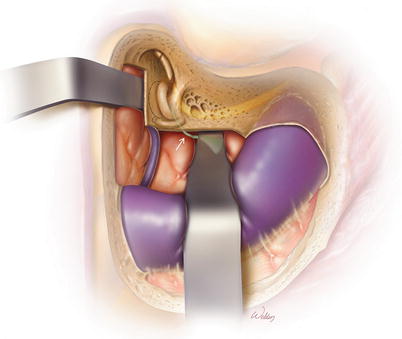

Malleable retractors were placed between otic capsule bone and the dura to reduce the chance of damaging the dura in case the drill slips during the labyrinthectomy. A cottonoid was placed over the sigmoid sinus and compressed by the retractor. There was a piece of surgical under it, which covered a small area of bleeding from the sigmoid sinus.

The air cells over the facial nerve still needed to be removed (arrowhead). The fossa incudis (arrow) can also be seen. This is as far forward as it needs to be opened.

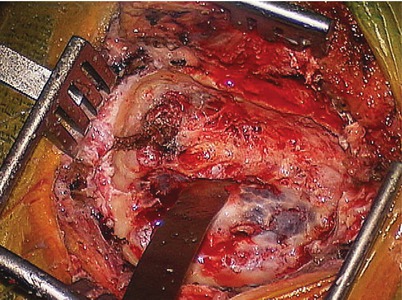

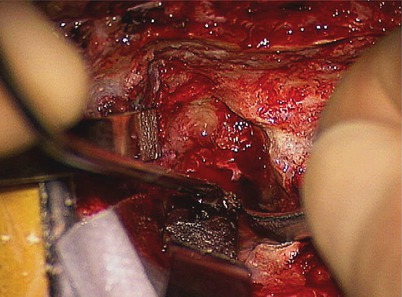

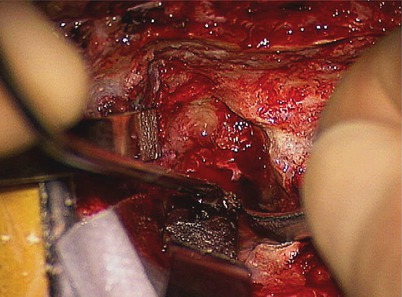

24.

The rest of the approach was performed, and most of the tumor was removed (not shown). After debulking the mass of the tumor in the cerebellopontine angle, the dura of the internal auditory canal was opened and the tumor teased out of the fundus with division of the superior and inferior vestibular nerves. This image, taken after all of these steps were performed, demonstrates the transverse crest (arrow) and the facial nerve (arrowhead).

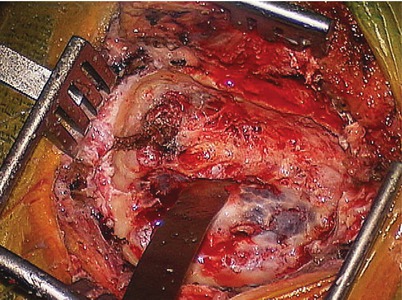

25.

Continuing the dissection to the mid-cerebellopontine angle, the facial nerve (arrow) can be seen along the anterior aspect of the tumor capsule. Extreme care must be taken not to stretch the facial nerve during the process of separating the tumor from the nerve.

26.

Immediate post-op axial T1 MRI with gadolinium and fat saturation demonstrated a total tumor resection. The slight amount of enhancement along the cerebellar peduncle represents inflammation, not tumor.

27.

Precontrast T1 MRI without fat saturation demonstrated the extent of the fat graft placement. Also, the white discoloration to the cerebellar peduncle represents postoperative blood and should be expected after the resection of larger tumors.

28.

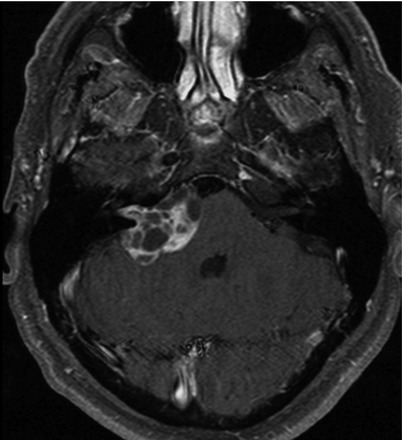

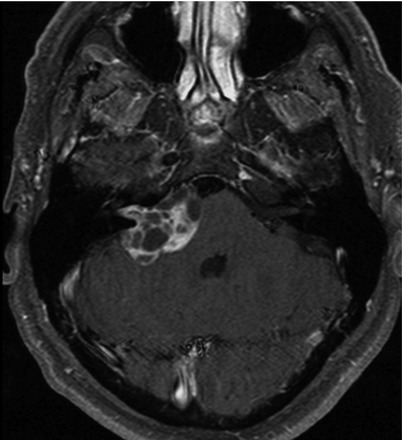

Case 2. A multicystic vestibular schwannoma.

29.

Postoperative image demonstrating a subtotal resection. A subtotal resection was selected for this patient based on his older age and comorbidities. With the availability of postoperative stereotactic XRT (i.e., Gamma knife, Cyberknife, Novalis, proton beam), this approach is becoming more commonplace. Typically, we only recommend post-op stereotactic XRT if the tumor remnant demonstrates growth on serial MRI. A small remnant like this usually will “ball up” into a well-circumscribed mass within 6–12 months. This makes it relatively straightforward to deliver an adequate radiation dose to the tumor remnant while minimizing unwanted exposure to the brainstem and inner ear.

30.

Case 3. Axial MRI with gadolinium of a patient with a medium-sized right vestibular schwannoma. The tumor extends to the fundus of the internal auditory canal. A subtotal dissection was planned for this patient according to his wishes to minimize the risk of any (even temporary) facial nerve dysfunction.

31.

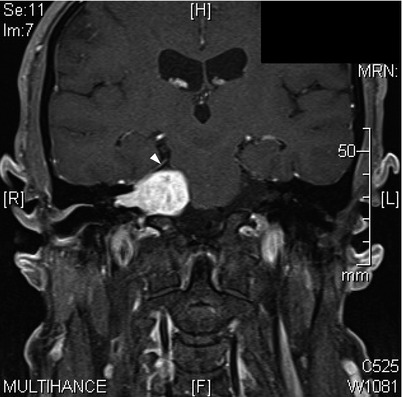

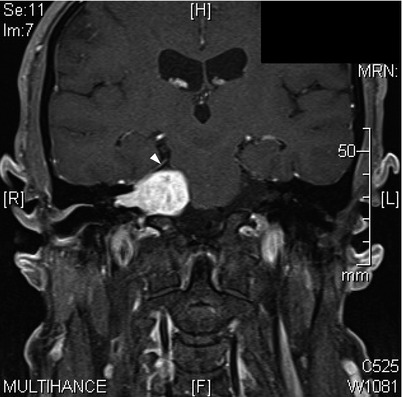

Coronal view of the tumor. The superior extent of the tumor is the tentorium (arrowhead).

32.

Fiesta T2-weighted MRI demonstrating that only a thin crevice of CSF is present within the distal internal auditory canal (arrow). Care must be taken during surgery to resect the lateral-most extent of the tumor.

33.

After opening the postauricular incision, drilling was performed to identify the sigmoid sinus and expose the retrosigmoid dura.

34.

After thinning the bone over the sigmoid sinus, a malleable was placed between the posterior fossa dura and the bone.

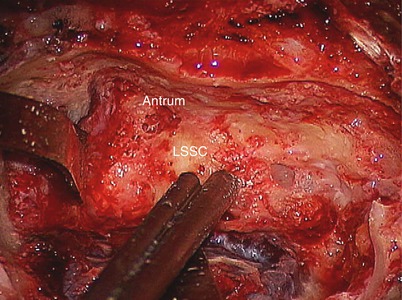

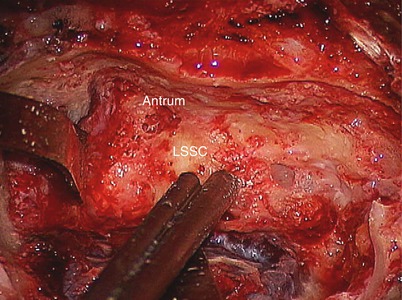

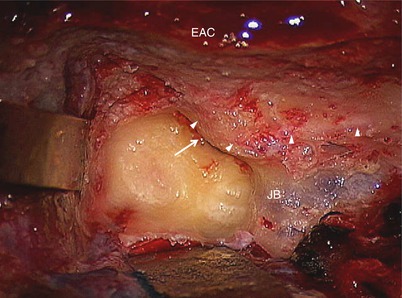

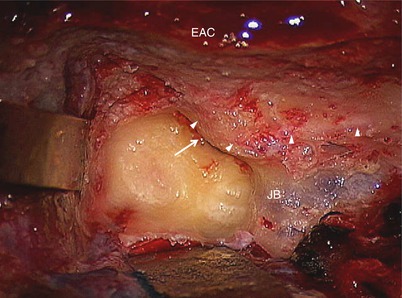

35.

The mastoidectomy was completed and the tegmen removed, allowing the superior retractor to be placed between the middle fossa dura and the bone. The lateral semicircular canal (LSSC) can be seen.

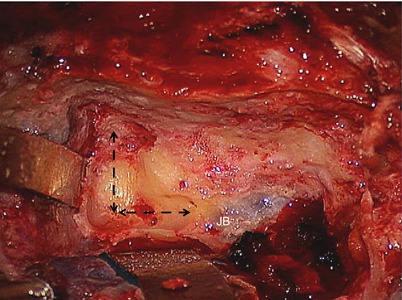

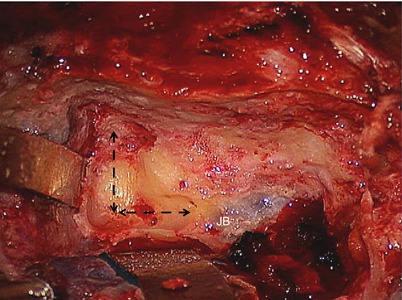

36.

The labyrinthectomy was begun by using a 4 mm cutting burr to drill troughs that parallel the middle fossa and posterior fossa dura (arrows). This is not a “canal exploration,” and so there is no need to nicely blue-line each canal. The goal is to get to the tumor quickly so that time can be spent on the tumor microdissection. This approach of drilling parallel to the dura quickly advances the dissection medially in a safe fashion. The jugular bulb (JB) is visible through the bone.

37.

As the bone was removed, the endolymphatic duct (arrow) could be seen running from the endolymphatic sac in the dura to the posterior petrous bone. This was then divided with an 11 blade scalpel.

38.

After completing the labyrinthectomy, the facial nerve was defined along its horizontal and vertical segments (arrowheads). Also, note how thin the ear canal bone is (EAC). These steps are critical to perform when resecting larger tumors as inadequate thinning of these structures will limit the ability to view the interface between the posterior face of the tumor and the cerebellar peduncle. For smaller tumors, it is not that important.

The vestibule (arrow) was opened under the second genu. The jugular bulb (JB) was the inferior limit of exposure. In this case, it was higher than optimal, but there was still plenty of room for tumor removal. A bone covering was left over it to reduce the risk of accidentally puncturing it during tumor removal.

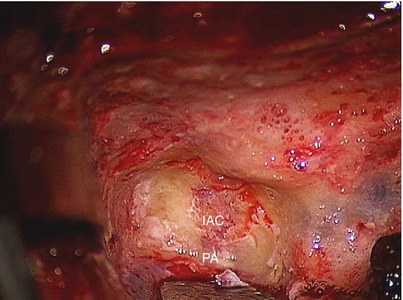

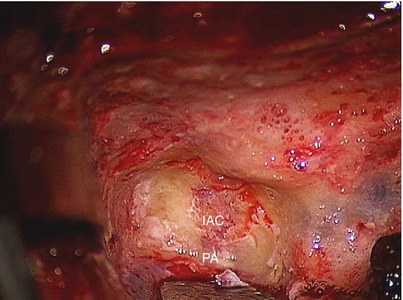

39.

To find the internal auditory canal, the porus acusticus (PA) was first identified by drilling along the posterior fossa dura. Then, the length of the internal auditory canal (IAC) was delineated.

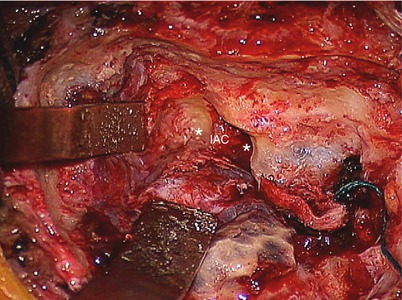

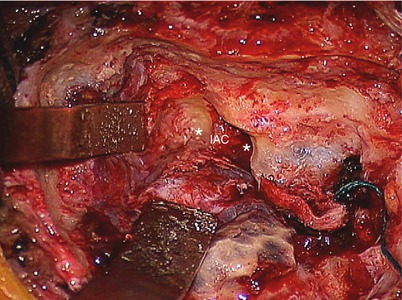

40.

Troughs (asterisks) were drilled superior and inferior to the internal auditory canal (IAC). The superior trough was deeper than the inferior trough in this case because of the relatively high jugular bulb. Note the cottonoid pledget in the “crotch” of the sigmoid sinus. The sigmoid sinus often bleeds in this area because its dural lining is very thin.

41.

The posterior fossa dura was opened. A moist Telfa strip was placed on the cerebellum and the retractor positioned. A #2 Penfield retractor was placed under the tumor to gently open the arachnoid membranes and release cerebrospinal fluid. This maneuver is important because it lowers the intracranial pressure and allows the brain to relax, providing more space to perform the dissection.

42.

The cerebellum was under the retractor, and the posterior face of the tumor was exposed. Testing with the nerve stimulator was performed to verify that the facial nerve was not in this area.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree