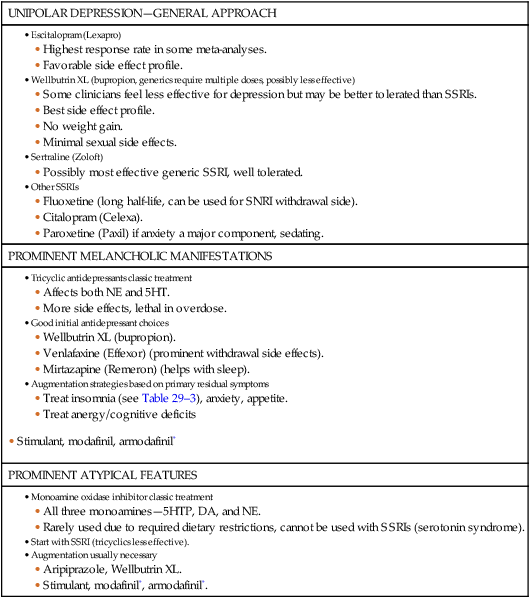

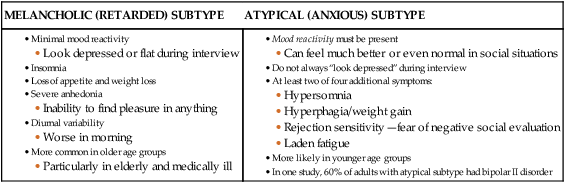

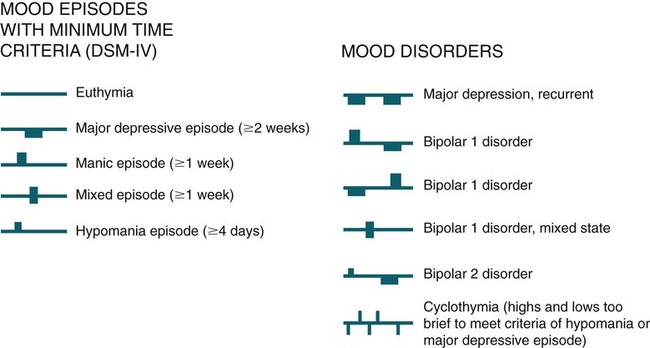

• A significant proportion of patients with a sleep complaint have a psychiatric illness and a significant number of patients with a psychiatric illness have a sleep complaint. • Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day is one of the nine major criteria for diagnosis of an MDE. • During an MDE, approximately 80% of patients complain of symptoms of insomnia (frequent awakenings, early morning awakening) and 20% complain of hypersomnia. • PSG during a depressive episode shows a long sleep latency, reduced sleep efficiency, reduced stage N3, a short REM latency, a longer first REM period, and a higher REM density early in the night. Early morning awakening may also be present. • Insomnia can precede an MDE and is often the last symptom of depression to resolve. Some but not all studies suggest that the persistence of sleep complaints is a risk factor for relapse of depression. • During MEs, the patient reports a decreased need for sleep (feeling rested on a few hours of sleep). Sleep loss can precipitate an ME. • Hypomanic episodes have characteristics similar to those of MEs except for the following three conditions: severe impairment is not present, hospitalization is not necessary, and there are no psychotic features. If any of the three are present, the episode is considered an ME. • A summary of duration criteria for the mood episodes: • Bipolar disorder I requires: • A current (or recent) hypomanic, ME, mixed episode, or MDE. • If the current episode is hypomanic or an MDE, there must be history of a prior mixed episode or ME. • Note that, unlike diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder II, the presence of at least one MDE is not required. • Bipolar disorder II consists of at least one hypomanic episode, one or more depressive episodes, and no history of current (or prior) MEs or mixed episodes. • Relapse rates for bipolar disorder patients are very high, even on maintenance therapy. Bipolar disorder is a significant risk factor for suicide. • Most patients with nocturnal panic attacks have similar episodes during the day. However, panic attacks can occur mainly at night and must be differentiated from NREM parasomnias such as sleep terrors. • The treatment of panic disorder includes behavioral psychotherapy/relaxation techniques, an SSRI (e.g., paroxetine or sertraline), and an antianxiety medication such as alprazolam or clonazepam. The SSRI is typically started in a low dose in combination with an antianxiety medication to prevent initial worsening of symptoms. The antianxiety medication can later be tapered in many cases. • Disturbing nightmares are a significant problem impairing sleep in PTSD. Imagery rehearsal therapy and prazosin are two relatively new treatment options. Psychiatric disorders are among the most common health problems, with over 15% to 20% of Americans being treated for a significant psychiatric illness in any given year.1 Almost one third of individuals with significant complaints of insomnia or hypersomnia show evidence of psychiatric disorders.2–5 Psychiatric disorders account for the largest diagnostic category for patients with sleep complaints. Conversely, sleep complaints are part of the diagnostic criteria for many psychiatric disorders and are a source of considerable morbidity. The psychiatric disorders commonly affecting sleep (or vice versa) are listed in Box 29–1. A number of depression scales are available for use by the sleep clinician in helping evaluate patients for possible depression or measuring improvement with treatment. The Beck Depression Inventory was mentioned in Chapter 25 on insomnia.6 The Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) is a 17, 21, or 24 question instrument that is widely used for research.7 The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) is a 10-item diagnostic questionnaire used to measure the severity of depressive episodes in patients.8 It was developed to be sensitive to the changes brought on by antidepressants and other forms of treatment. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a short 9-question instrument (Appendix 29–1)9 that the patient can quickly fill out and is easy to use. The PHQ-9 has been validated and may be used to screen patients with sleep disorders for depression. A major depressive episode (MDE; Box 29–2) is defined by five (or more) of the following nine symptoms having been present during the same 2-week period and representing a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition [DSM-IV]).2 2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure.* 3. Significant weight loss, when not dieting, or weight gain, or decrease or increase in appetite. 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day. 5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings or restlessness or being slowed down). 7. Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick). 8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness nearly every day.† 9. Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or specific plan for committing suicide. MDEs are sometimes divided into melancholic and atypical subtypes (Box 29–3). The melancholic subtype is associated with insomnia whereas hypersomnia is characteristic of the atypical subtype. The melancholic subtype usually has worse symptoms in the morning. An atypical depressive episode is also characterized by mood reactivity (ability for mood to temporarily improve in response to a positive or stimulating situation), increased appetite and weight, laden fatigue (a sense of heaviness or being weighed down), and rejection sensitivity (fear of social rejection). Unipolar depressive episodes are more often of the melancholic type and the atypical subtype is more characteristic of bipolar depressive episodes. The impact of an MDE on sleep is summarized in Box 29–4. A sleep complaint (insomnia or hypersomnia) is one of the primary diagnostic criteria for an MDE. Nearly 80% of depressive episodes are associated with insomnia.3,4 The insomnia complaints include early morning awakening and frequent awakenings. However, up to 15% to 20% of patients complain of hypersomnia during an MDE. The polysomnography (PSG) findings in patients during an MDE4,5 include a prolonged sleep latency, increased wake after sleep onset, decreased stage N3, and rapid eye movement (REM; stage R) abnormalities. The stage R abnormalities include a short REM latency, an increased length of the first REM episode, and an increased REM density in the early part of the night. Recall that the REM density (number of REMs per time) is typically low during the first REM episodes. Symptoms of insomnia or PSG abnormalities may persist after remission of depression.5,10–14 Rush and coworkers10 found a short REM latency (<65 min) in 11/13 patients during active depression, and in those 11 patients, a short REM latency persisted in 8 after clinical remission. Dombrovski and colleagues14 found that anxiety and possibly residual sleep disturbance predicted early recurrence. However, Yang and associates15 did not find that persistent sleep disturbance predicted recurrence. Even if patients with an MDE complain of hypersomnia, the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) does not usually reveal severe sleepiness.3,4,16 Manic episodes (MEs) are distinct periods of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, lasting at least 1 week (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary) (Box 29–5). If the mood is irritable, four of the following are needed, otherwise three of the following2: 1. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity. 2. Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after 3 hr of sleep). 3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking. 4. Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing. 5. Distractability (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli). 6. Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation. 7. Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments). In mixed episodes, criteria are met both for an ME and for an MDE (except for duration) nearly every day during at least a 1-week period.2 The disturbance is sufficiently severe to cause marked impairment in occupational function or in usual social activities or relationships with others or to necessitate hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others, or there are psychotic features. Symptoms are not due to the direct physiologic effects of a substance (e.g., drug of abuse, a medication, or other treatment) or general medical condition (e.g., hypothyroidism). The mixed episode combines symptoms of both mania and depression. The patient may be effusive and grandiose one moment and crying the next (Box 29–7). A hypomanic episode is a distinct period of persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, lasting throughout at least 4 days, that is clearly different from the usual nondepressed mood (Box 29–8).2 During the period of mood disturbance, three (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted (four if the mood is only irritable) and have been present to a significant degree: 1. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity. 2. Decreased need for sleep (rested on 3 hr of sleep). 3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking. 4. Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing. 6. Increase in goal-directed activity or psychomotor agitation. 7. Excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments). Episodes of hypomania are associated with an unequivocal change in functioning that is uncharacteristic of the person when she or he is not symptomatic. Of note, the disturbance in mood and the change in functioning are observable by others. Although all the previous statements are similar to those of MEs, the following differentiate hypomania from mania. The hypomania episode is NOT SEVERE enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational function, or to necessitate hospitalization, and there are NO psychotic features (no delusions or hallucinations are present). Note that a diagnosis of a hypomanic episode requires a minimum duration of 4 days whereas the minimum duration of symptoms for diagnosis of an ME is 1 week (see Box 29–8). The major mood disorders are listed in Box 29–9. This is not a complete list. For additional disorders refer to the DSM-IV.2 These mood disorders are diagnosed based on occurrence of mood episodes (Fig. 29–1). The MDDs include (1) MDD—single episode or (2) MDD—recurrent (Box 29–10).2 To be considered separate episodes, the depressive episodes must be separated by at least 2 consecutive months in which diagnostic criteria for MDE are not met. In MDD, there is NO history of a manic, mixed, or hypomanic episode. MDD is sometimes called “unipolar depression.” At least 60% to 80% of patients with an MDD report at least one of the following sleep complaints: difficulty falling asleep (38%), frequent awakenings (39%), or early morning awakening (41%) (Box 29–11).3,13 Subjective complaints of insomnia may improve but are not necessarily normalized with remission from major depression.12–15 Insomnia is often the last symptom to improve in patients treated for MDD. In addition, insomnia is the most common residual complaint in patients who have recovered from depression. Some studies have suggested that the persistence of sleep disturbance during remission from depression is predictive of a relapse.13,14 However, a recent double-blind withdrawal of fluoxetine (FLX) after successful treatment15 was unable to show a predictive value of residual sleep disturbance for the risk of recurrence of depression. Patients having a response to FLX during an open-label study received placebo or FLX during withdrawal. Sleep components of the HAMD were used to determine whether residual sleep complaints correlated with an increased chance of relapse. No sleep complaint was associated with higher rate of relapse of depression. Depression and insomnia appear to have a reciprocal relationship because insomnia frequently precedes the onset of depression and has been found to be strongly predictive of future depressive episodes. Individuals with persistent insomnia have been found to be 4 to 10 times more likely to subsequently develop depression than those with short-term insomnia or no insomnia.22 Patients with depression and persistent insomnia are 1.8 to 3.5 times more likely to remain depressed, compared with patients with no insomnia.23 Of interest, sleep deprivation or restriction has been found to have an acute antidepressant effect on patients with unipolar depression.24,25 With recovery sleep, 50% to 80% of patients have a relapse. As noted previously, sleep loss can also precipitate mania in some patients. A detailed discussion of the treatment of depression is beyond the scope of this chapter. Psychotherapy and medications are often used alone or in combination. Many antidepressants are available.26–33 Often, the choice is based on side effects and which symptoms are most prominent (anxiety, fatigue). Individual patients may respond to a different medication if treatment with an initial antidepressant is not successful. It is important to get a good drug history. If a patient previously responded to a medication, he or she is likely to have a good response again (Table 29–1). The older tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) block the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine and are effective treatment for depression. However, the TCAs are not selective in the blockade of receptors and are associated with prominent anticholinergic side effects (constipation, dry mouth). They are also lethal in overdose. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are safer in overdose and in general have fewer side effects than TCAs. They vary in a number of properties. For example, the half-life of FLX is very long. The SSRIs can cause either daytime sedation or insomnia. If they cause insomnia, they should be given in the morning. If they cause sedation, they should be given at bedtime. SSRIs can also have prominent sexual side effects or result in weight gain in some patients. There is some evidence that escitalopram (Lexapro) is the most effective (or at least as effective)29,30 for unipolar depression as other commonly used antidepressants and is well tolerated. Escitalopram also has fewer drug interactions than many other antidepressants. Some studies suggest that citalopram (racemic) is less effective than escitalopram. If escitalopram cannot be used due to financial issues, sertraline is a good alternative. TABLE 29–1 An approach for choosing an antidepressant for treatment of depression is listed in Table 29–2. If the patient has prominent melancholic or atypical features, one might consider different medications. If the patient does not respond to an effective dose of the initial medication, either trial of another medication or the addition of another agent (augmentation) could be considered. Note that the serotonin syndrome (agitation, tachycardia, hyperthermia) can rarely occur when two medications blocking serotonin re-uptake are used together. The syndrome is most common with use of an SSRI + MAOI (contraindicated). Do not start an SSRI until a MAOI has been stopped for 21 days. Do not start a MAOI unless an SSRI has been stopped for up to five weeks (depending on SSRI half-life). TABLE 29–2 Factors to Consider in Choosing an Antidepressant

Psychiatry and Sleep

Mood Disorders

Depression Questionnaires and Severity Rating Scales

Mood Episodes

Major Depressive Episode

Impact of MDE on Sleep

Manic Episode

Mixed Episode

Hypomanic Episode

Mood Disorders

Major Depressive Disorder

Sleep and MDD

Treatment of Depression

UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION—GENERAL APPROACH

PROMINENT MELANCHOLIC MANIFESTATIONS

PROMINENT ATYPICAL FEATURES