Flow voids in the basal ganglia are demonstrated bilaterally on axial T1 MRI (see arrows). This is representative of hypertrophy of the basal ganglia perforator arteries.

Unenhanced MRI axial FLAIR sequence demonstrates leptomeningeal high signal or “ivy” sign (most prominent on left hemisphere) (see arrows). Although the pathogenesis of the ivy sign is uncertain, it is thought to represent slow flow in engorged pial vessels.

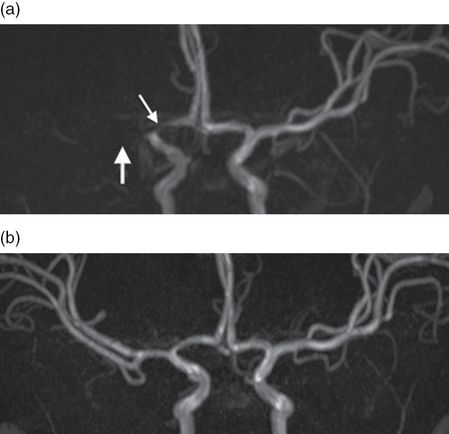

Magnetic resonance angiography of the anterior circulation demonstrates bilateral stenosis of the terminal internal carotid arteries with flow gaps in the proximal middle and anterior cerebral arteries as well as hypertrophied perforator arteries.

A diagnosis of moyamoya disease was made and the patient was commenced on low dose (3 mg/kg/day) aspirin. No further transient ischemic attacks occurred within the subsequent 2–3 months. However, due to the ongoing risk of cerebral ischemia and the potential for cognitive decline in moyamoya [9], a neurosurgical assessment was requested. The neurosurgeon counseled the family regarding surgery and shortly thereafter, bilateral indirect revascularization surgery was performed. One brief TIA occurred 2 weeks following surgery; however, to date he has had no further TIAs and follow-up MRI again did not show evidence of deep white matter or vascular territorial infarction. He remains on aspirin.

Discussion

Potential difficulties in the recognition of TIAs in children are highlighted by this case. This child’s initial event was incorrectly thought to be a focal seizure. Other common differential diagnoses of TIA are listed in Table 2.1. Analysis of the clinical characteristics of focal seizures and TIAs assists in differentiation between these two entities. Both seizures and TIAs have a sudden onset, although an aura may precede a focal seizure. The duration of a focal seizure (usually <1 minute) is typically shorter than a TIA, although both can be of very short duration. In this case the events lasted 10–30 minutes and this is more consistent with TIAs. Sensory symptoms during seizures are usually “positive” type symptoms such as tingling or pins and needles rather than the “negative” symptoms of numbness or sensory loss as seen in this child. Focal seizures are stereotyped and alternating sides are uncommon in focal epilepsy, secondary to a structural lesion. The alternating of sides in this case was in keeping with the finding of a bilateral arteriopathy. The frequency of events is also an important consideration. If episodes occur very often with full neurologic recovery, then this would favor a diagnosis of focal epilepsy.

Hemiplegic migraine: familial or spontaneous |

Migraine with other focal neurological auras |

Focal seizures +/– postictal (Todd’s) paresis |

Functional disorder |

Brain tumor with hemorrhage |

Demyelination |

Acute cerebellar ataxia of childhood |

Peripheral vestibulopathies |

Metabolic or toxic conditions: MELAS, hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia |

Peripheral nerve or nerve root disorders with unilateral focal deficits |

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) |

Syncope |

Channelopathies: alternating hemiplegia of childhood and episodic ataxia |

MELAS: mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like events.

This case also highlights the need for early MRI brain and cerebral vascular imaging. Due to the delayed recognition that this child was having TIAs, and possibly due to the false reassurance provided by the CT brain, MRI brain and vascular imaging were not performed until 4 months after symptom onset. Brain CT may miss 50–80% of childhood strokes that are later confirmed on MRI. [10,11] Also, as seen in this case, CT will not detect certain characteristic imaging features of moyamoya that can be seen on MRI. Vascular imaging was critical as the finding of an arteriopathy supported a clinical diagnosis of recurrent TIAs and guided further investigations and management. As arteriopathies such as moyamoya are very important causes of cerebral ischemia in childhood, vascular imaging must be strongly considered in all children with suspected TIA or AIS. Other risk factors for stroke in children and young adults are outlined in Table 2.2.

Children | Young adults | |

|---|---|---|

Arteriopathies | Inflammatory arteritis (e.g., transient cerebral arteriopathy; post-varicella angiopathy; bacterial meningitis; HIV; other infections) Moyamoya Cervicocephalic arterial dissection Radiation-induced vasculopathy Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome | Inflammatory arteritis (e.g., Takayasu’s, hepatitis B and C, HIV) Moyamoya Cervicocephalic arterial dissection Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome Radiation-induced vasculopathy Atherosclerosis Small vessel disease |

Cardiac | Congenital heart disease Acquired heart disease Cardiac surgery or catheterization Mechanical circulatory support devices Patent foramen ovale | Acquired heart diseases (cardiomyopathy, ischemic heart disease) Congenital heart disease Cardiac surgery or catheterization Mechanical circulatory support devices Patent foramen ovale |

Hematological | Prothrombotic disorders Sickle cell disease | |

Vascular risk factors promoting atherosclerosis | Hypertension (rare) | Hypertension Diabetes mellitus Dyslipidemia Obesity Smoking |

Other | Migraine with aura Illicit drugs Alcohol abuse Obstructive sleep apnea Oral contraceptive pill Pregnancy Inborn errors of metabolism (rare) | |

The term moyamoya describes a progressive arteriopathy involving the terminal portions of the internal carotid arteries and their branches with hypertrophy of the deep perforating arteries [12]. Moyamoya disease is the term used when moyamoya occurs in isolation without associated medical conditions including sickle cell disease or syndromes such as neurofibromatosis type 1 or Down syndrome. In moyamoya, cerebral ischemia is thought to occur secondary to both chronic hypoperfusion and thromboembolism. Characteristic of moyamoya, cerebral ischemia may be precipitated by hyperventilation induced by crying, blowing, physical exertion, or ingestion of a hot meal, therefore a history of precipitating factors should be sought. Spontaneous TIAs can also occur, as seen in this child.

Pediatric guidelines suggest using aspirin as initial therapy for children with moyamoya, although the level of evidence is low [13,14]. Anticoagulation is generally avoided because of concerns about bleeding, a common form of stroke in adults with moyamoya. Children with moyamoya should be promptly referred to a neurosurgeon with expertise in moyamoya. Revascularization surgery may be indicated, particularly if there are recurrent clinical symptoms presumed secondary to cerebral ischemia or if abnormalities have been demonstrated on cerebral blood flow studies such as single photon emission tomography (SPECT) with acetazolamide, or cerebrovascular reactivity study with hypercarbia challenge [15]. Revascularization surgery results in improvement in clinical symptoms in approximately 90% of children [16]. Direct (in older children) or indirect revascularization procedures may be performed. The timing of surgery and the surgical approach depend on a number of factors and although proposed guidelines exist [17], decisions are best made on a case-by-case basis in a center with expertise in moyamoya.

Case 2

Case description

A 5-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after having acute onset of left-sided weakness at school. Her past medical history was significant for an uncomplicated chicken pox infection 2 months prior. While sitting in the classroom, her teacher noticed that she was unable to move her left arm, was drooling from the left corner of her mouth, and was unable to walk. An ambulance was called and she was taken to the emergency department. On examination there it was described that she could “barely” move the left arm and leg and there was a clear left facial droop in the upper motor neuron distribution. It was also suspected that she had diminished sensation down the left side in the same distribution as her motor weakness. She made a full recovery within 3 hours and was discharged from hospital. The following day she returned to the emergency department after having a near identical episode, again with complete recovery. A brain MRI was performed and this demonstrated diffusion restriction in the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory (involving the cortex and basal ganglia) consistent with acute infarction (Figure 2.4). The MRA demonstrated occlusion of the proximal right MCA and probable narrowing of the proximal portion of the right anterior cerebral artery (ACA). She was commenced on intravenous unfractionated heparin and as a part of standard neuroprotective care, close attention was given to maintenance of normal blood pressure, temperature, glucose, and hydration status. There was vigilant clinical monitoring for seizures.

The following day, while in hospital, she had an episode that consisted first of drooling from the left corner of the mouth and involuntary flexion of the left arm. This lasted 1 minute and was followed by moderate left arm and leg weakness. The weakness resolved within 15 minutes. It was uncertain whether or not altered awareness was present at the onset of the episode. An EEG demonstrated right-sided frontal slowing without epileptiform discharges. However, she was administered a loading dose of intravenous phenytoin as she was suspected to have had a focal seizure followed by postictal paresis. A repeat brain MRI/MRA was performed and this did not demonstrate any new areas of cerebral infarction, or hemorrhagic conversion. The MRA demonstrated return of flow through the proximal MCA (M1) with residual stenosis at the site of prior occlusion. Conventional angiography confirmed stenosis and irregularity of the right A1 and M1. A lumbar puncture revealed a lymphocytic pleocytosis with 17 × 106 white cells. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) bacterial culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for viral infections were negative. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated at 45 mm/h. Investigations for systemic inflammation and/or autoimmunity such as antinuclear antibody (ANA) were negative. A prothrombotic evaluation and transthoracic echocardiography did not demonstrate any abnormalities.

A diagnosis of transient cerebral arteriopathy (TCA) with a probable inflammatory basis was made. Due to the substantial risk of recurrent stroke or TIA in children with TCA, the initial treatment with unfractionated heparin was followed by transition to low molecular weight heparin. The decision was made to avoid immunosuppressive therapy agents despite the presumed inflammatory basis, due to the generally observed spontaneous resolution of arteriopathy in TCA despite conservative treatment. During follow-up no further events occurred and over the course of 6 months, MRA demonstrated significant improvement in the right MCA and ACA stenosis, prompting transition from anticoagulation therapy with low molecular weight heparin to antiplatelet therapy with aspirin. An MRA 4 years later demonstrated complete normalization of the right MCA and ACA (Figure 2.5).

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA): initial (a) and 6-month follow-up (b). The initial MRA shows complete occlusion of the proximal MCA (M1, thick arrow) and stenosis of the proximal ACA (A1, thin arrow) on the right. Follow-up imaging 6 months later shows near complete resolution with only mild reduction in caliber of the right A1 and M1.

Discussion

This case demonstrates the need to maintain a high index of suspicion for TIA and stroke in children. Despite having an episode of sudden onset hemiparesis, she was discharged from the emergency department without a diagnosis. Hemiparesis is the most common symptom of cerebral ischemia and should prompt strong consideration of TIA or AIS regardless of patient age. Early identification would have allowed for timely investigations and management in this case, perhaps preventing irreversible cerebral injury. Characteristic features of TIA and its differential diagnoses are outlined in Table 2.3. The challenges and important factors to differentiate between TIA or AIS and postictal paresis are illustrated by this case. Postictal paresis can occur following a focal or apparent generalized seizure and identification of suspected seizure activity, such as the tonic posturing seen in this case, preceding the onset of weakness is crucial for diagnosis. However, seizures are a common presenting feature of childhood stroke [18] so a brain MRI is often required to rule out AIS, particularly in a first episode of postictal paresis. Clinical experience suggests that seizures do not occur as a feature of TIA in childhood; however, large studies of TIA in the pediatric population are lacking. Since rapid recovery and brief duration of hemiparesis are common in both TIA and postictal paresis these characteristics are not necessarily helpful in differentiating the two conditions [19]. A past history of epilepsy should be sought, as this is a supporting feature of postictal paresis.

Onset | Symptoms | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

TIA | Sudden onset; deficit maximal at onset | Negative symptoms | Minutes to hours. The majority last <60 minutes |

Hemiplegic migraine | Gradual progression of symptoms over 20–30 minutes | Motor aura occurs with at least one other aura symptom. Almost always accompanied by headache | Typically >20 minutes. Most resolve in <60 minutes but may last up to 72 hours |

Migraine with aura | Gradual development of aura; symptoms evolve over 5–20 minutes | Positive and/or negative aura symptoms; visual aura most common Headache occurs following aura but can occur with aura or within 60 minutes of aura | Each individual aura symptom lasts 5–60 minutes |

Post-ictal paresis/Todd’s paresis | Weakness follows focal motor seizure and is maximal at onset | Weakness is usually mild to moderate. May have past history of focal seizures | Duration typically ranges from seconds up to 30 minutes, with some reported cases of up to 36 hours duration |

The provisional diagnosis of transient cerebral arteriopathy was made in the context of vascular imaging demonstrating a unilateral stenosing arteriopathy involving the proximal portions of the right middle and anterior cerebral arteries. Given that this child had a varicella infection 2 months prior to her stroke, the most accurate diagnosis would be post-varicella angiopathy (PVA). Transient cerebral arteriopathy and post-varicella angiopathy are both terms for unilateral non-progressive arteriopathies of childhood [20]. Both are suspected to have an inflammatory basis and are major causes of childhood TIA and stroke. Due to the presumed inflammatory basis some centers may treat select patients with TCA and/or PVA with immunosuppressive therapy (typically corticosteroids), as for any other form of central nervous system vasculitis. Treatment with immunosuppressive agents remains controversial in these conditions, as there is a lack of evidence supporting benefit. For the majority of patients with TCA or PVA the arteriopathy spontaneously improves and is monophasic in nature [21]. If immunotherapy is used, the practice would likely include addition of acyclovir in cases of PVA.

Case 3

Case description

A 17-year-old female presented to the emergency department with left-sided weakness and sensory symptoms. After waking from a brief afternoon nap she noticed tingling of the left side of her face. Within a few minutes she developed a mild bilateral occipital headache. Over 5–10 minutes the tingling progressed to involve her left arm and leg. She got into her car to drive to work and noticed that her left arm and leg felt heavy and numb. When she arrived at work a colleague noticed drooping of the left side of her face and slurred speech. This was now 1 hour after initial symptom onset. On arrival in the emergency department her neurological examination demonstrated mild left arm and leg weakness. Her sensation was intact and there was no facial weakness or dysarthria. She made a full recovery within 2 hours of symptom onset. Brain MRI and intracranial and cervical time-of-flight MRA and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) were performed 6 hours after symptom onset and no abnormalities were demonstrated.

Her past history was significant for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the right lower limb 9 months prior to this presentation. The DVT was thought to be precipitated by trauma to the leg while playing hockey. She was also on the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) and prior prothrombotic testing had demonstrated heterozygosity for the factor V Leiden gene mutation. For the DVT she had been treated with an oral vitamin K antagonist and she remained on this at the time of presentation with hemiparesis. The international normalized ratio (INR) had been consistently within the target range of 2–3.

Her past medical history included intermittent mild “band-like” frontal headaches, most consistent with tension type headaches. There was no history of migraine in her immediate family. Doppler ultrasound of the right leg showed a persistent non-occlusive thrombus in the proximal superficial femoral vein. Transthoracic echocardiography and electrocardiography were normal. She was diagnosed with a probable spontaneous hemiplegic migraine and was discharged home the following day.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of hemiparesis is broad and includes common stroke mimics such as hemiplegic migraine, postictal paresis, and functional disorders (Table 2.3). The two main differential diagnoses in this case were TIA or AIS and hemiplegic migraine (HM). A detailed history including mode of onset, symptom characteristics, and episode duration followed by careful analysis is critical for differentiating these two disorders. Difficulty can, however, arise due to atypical presentations and overlap in clinical features.

In this case the mode of onset was gradual and progressive with spreading of symptoms from face, to arm and leg and from sensory to motor, over 30–60 minutes. This is typical of HM where the aura symptoms characteristically slowly evolve. Although rare, symptoms can rapidly evolve over less than 1 minute in HM [22]. Her sensory symptoms were initially positive (tingling) but then became negative (numbness) and this evolution from positive to negative symptoms is common in HM. Headache occurs in the majority of patients with HM and usually has the characteristics of a typical migraine headache (e.g., unilateral and pulsating in nature) but mild nonspecific headaches, as seen in this patient, can occur. Headaches also occur in up to 20–40% of patients with cerebral ischemia, so the differentiating value of headache alone is limited [23,24]. A past history of migraine with aura, particularly if there have been previous similar episodes, may be helpful; however, it is important to remember that migraine is common and a past history of migraine may also be present in young patients with stroke [25]. Hemiplegic migraine can be spontaneous or familial so it is important to seek a family history as this may assist in the diagnosis.

This case was also complicated by the history of deep vein thrombosis. Although a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was not demonstrated on transthoracic echocardiography, paradoxical embolism resulting in cerebral ischemia should still be considered due to the possibility of a false negative echocardiogram and also because right-to-left shunting can occur at the pulmonary level. However, taking into account all of the clinical characteristics, the final diagnosis in this case was hemiplegic migraine. Regardless, investigations for TIA including MRI/MRA brain, echocardiography, and a prothrombotic work-up were performed before excluding this possible diagnosis. This is advisable in any first episode of suspected HM and also in subsequent episodes if the symptoms of an event are atypical for an individual.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree