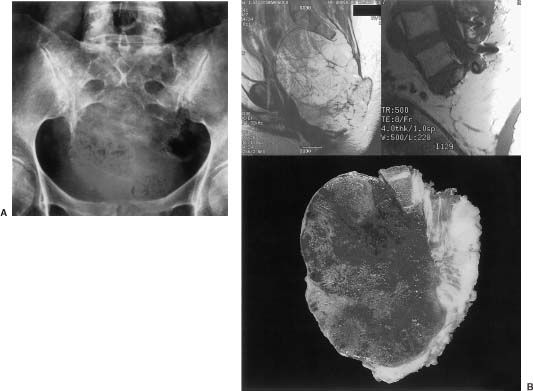

25 Tumors of the sacrum and related neural, retroperitoneal, and pelvic structures are rare, accounting for between 1 and 7% of all spinal tumors that come to clinical attention.1 The types of tumors that may be encountered in this region are diverse, and treatment options are intricately related to the medical status of the patient, the location and extent of the lesion, and the biologic aggressiveness of the tumor type. The diagnosis of sacral lesions is frequently delayed, and tumors may be far advanced at the time of presentation. Surgical resection is complicated by the complex anatomy of the sacral region; therefore, a multidisciplinary surgical team is required. Major sacral resections are highly morbid procedures. In the case of high sacral lesions in particular, complete resection can require the sacrifice of sacral nerve roots and may jeopardize lumbopelvic stability. Combined multimodality therapy, including irradiation and chemotherapy, may improve the long-term diseasefree survival for certain tumor types. Some highly aggressive lesions are best not treated with surgical resection but, rather, with radiation therapy or chemotherapy alone. This chapter outlines the evaluation of patients with sacral tumors and discusses the relevant clinical, radiologic, and pathologic characteristics of the different tumor types. The current therapeutic options for patients with sacral tumors and the results of therapy are also discussed. See Chapter 44 for details of the anatomy, biomechanics, and surgical approaches to this region. Chapter 41 describes methods of lumbosacral and pelvic reconstruction and stabilization. Sacral tumors are rare and difficult to diagnose at an early stage. In one report, a delay in diagnosis of 2 years or more occurred in six of the nine patients studied.1 The major reasons for this delay include (1) the unique capacity of the sacral canal to allow neoplastic expansion without causing symptoms, (2) the often nonspecific nature of the complaints when they arise, and (3) the difficulty in obtaining and interpreting adequate imaging studies. As a tumor expands within the sacral canal, it may erode or invade the walls of the sacrum, expand cephalad within the spinal canal, or enter the pelvis through the ventral sacral foramina. A slow-growing regionally expansive neoplasm may obtain a large size without causing symptoms early in the course of the illness. Aggressive or malignant tumors tend to present earlier and have a more dramatic clinical presentation.1 The earliest presenting symptom in patients with sacral tumors is pain located in the lower back or sacrococcygeal region.1–3 Referred pain to the leg or buttock due to irritation of the first sacral root or iliolumbar trunk is also common. The early presentation of sacral lesions is therefore very similar to that of the much more common lumbar spondylosis. By the time a sacral lesion is diagnosed, many patients have been treated and sometimes even operated on for suspected lumbar intervertebral disc pathology. Abnormalities on plain sacral radiographs may be missed,4 and routine lumbar myelography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies frequently fail to visualize the sacrum below the S2 level. Unfortunately, the true diagnosis is frequently realized late in the course of illness, when bladder or bowel function have been compromised, or when a large presacral mass is noted on rectal or gynecologic examination. A sacral tumor can be easily overlooked on standard radiographs. The curved shape of the sacrum, its position within the pelvic girdle, and overlying bowel gas are frequent sources of obscuration. Further, destructive changes must be far advanced before they become evident on plain x-ray films (Fig 25-1A).4,5 Adequate radiographs should display the entire sacrum and coccyx on lateral views, and the sacrum should be visualized en face on anteroposterior views. A transpelvic view with the xray beam angled 20 to 30 degrees cephalad through the hollow of the sacrum is also useful because this view compensates for the acute angulation of the sacrum with respect to the lumbar spine.4 A malignant process is suggested when lytic lesions without sharply defined borders are seen. Well-defined sclerotic margins, reflecting reactive changes in the surrounding bone, imply the presence of a benign or chronic process. Computed tomography and MRI more readily allow the detection, characterization, and staging of sacral tumors. 5,6 CT has the advantage of providing excellent bony detail and showing tumor matrix calcification. CT is also useful to image the abdomen for evidence of visceral involvement. The major advantages of MRI studies include the detailed depiction of associated soft tissue masses and the ability to assess the anatomy in multiple planes. The rostral extent of sacral involvement, which is particularly critical to surgical planning, is best appreciated on a midsagittal view (Fig 25-1B). The radionucleotide bone scan is a sensitive but nonspecific indicator of bone destruction that is most useful as part of a systemic workup to rule out widespread bony metastases during the preoperative staging of these patients. Purely osteolytic lesions, such as myeloma, may not be well defined on bone scans. Obscuration of sacral lesions by the accumulation of radioactive material in the bladder may result in falsely negative studies. FIGURE 25-1 (A) Anteroposterior radiograph of the sacrum demonstrates a lytic process involving the sacrum below S2. Chordoma was diagnosed on CTguided biopsy. (B) Findings for same patient as in A, who underwent high sacral amputation for sacrococcygeal chordoma. Preoperative (upper left) and postoperative (upper right) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveal involvement of the sacrum below the midportion of S1. Lower: Pathologic specimen, cut sagittally, demonstrates radical resection. (From York JE, Kaczaraj MS, Abi-Said D, et al. Sacral chordoma: 40-year experience at a major cancer center. Neurosurg 1999;44:74–80, with permission.) In addition to the bone scan, chest radiography and CT of the abdomen are also warranted as part of the preoperative assessment of patients with sacral lesions to rule out metastatic pathology. Pelvic angiograms are useful in defining the vascularity of sacral lesions and in planning preoperative tumor embolization, especially for highly vascular lesions such as giant cell tumors and aneurysmal bone cysts.7,8 The differential diagnosis of sacral tumors is extensive, although clinical and imaging factors may suggest a more abbreviated differential diagnosis. A biopsy should be performed in all cases where the decision to proceed with surgery or the extent of surgery would be influenced by the pathologic diagnosis. In patients with significant comorbid illness who are not considered candidates for major surgical resections, a biopsy may still be warranted to decide on appropriate alternate therapies. Although open biopsy was common in the past, the percutaneous CT-guided biopsy involves minimal risk and is currently the method of choice. The site of entry and the trajectory of the needle should be carefully selected so that they can be easily included within the margins of any subsequent resection. If possible, the puncture site should be located in the midline posteriorly. It may be worthwhile to introduce a small droplet of sterile permanent ink into the needle tract to “tattoo” the skin for later identification. A transrectal biopsy should not be considered, because an otherwise uninvolved rectum may be seeded with tumor cells necessitating later resection. Further, infection of the tumor bed following transrectal biopsy has been documented.9 The anatomic location within the sacrum, the direction of spread, and the biologic behavior of individual tumors depend primarily on the histologic type. There is no widely accepted scheme to classify the wide variety of neoplastic and nonneoplastic processes that may affect the sacral region. A broad differential diagnosis of the various lesions encountered in this area is provided in Table 25-1. Some processes are nonneoplastic, including developmental cysts and inflammatory conditions.

Sacral Tumors: Primary and Metastatic

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Radiologic Evaluation

Biopsy

Specific Tumor Types: Clinicopathologic Characteristics, Management Options, and Outcome

Specific Tumor Types: Clinicopathologic Characteristics, Management Options, and Outcome

|

Sacral tumors are categorized as those that originate from the neural elements or their supporting tissues, those arising from bone, and those tumors that are metastatic from distal sites or the result of direct invasion from adjacent pelvic structures. The most common sacral tumors are metastatic, whereas the most common primary sacral tumor is chordoma.3,10

A fundamental issue in determining the potential for surgical cure is derived from an evaluation of the invasiveness of the neoplastic process. Benign encapsulated tumors may be dealt with by simple lesional resection. A more aggressive approach, including a circumferential margin of uninvolved tissue, is required for many lowgrade malignancies with infiltrative borders. Malignant tumors of the sacrum are most successfully treated with a combination of radical excision and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Some very highgrade malignancies and disseminated cancers are best managed with radiotherapy or chemotherapy alone. Due to the complexity of the sacral anatomy and the close relationship of major neural structures and vital organs, the projected benefits of radical resection to achieve local control or cure must always be balanced against the functional consequences of treatment.

Congenital Lesions

Developmental tumors and other abnormalities account for a large portion of the pathology affecting the sacrococcygeal region. A discussion of some of the sacrococcygeal cystic lesions is warranted here because these lesions may resemble neoplastic disease in clinical practice.

Dermoid Cysts

Developmental cysts in the sacrococcygeal region tend to be more common in women and are frequently asymptomatic until the adult years. The most common developmental sacrococcygeal cyst is the dermoid cyst.11 Dermoid cysts are midline lesions that can arise anywhere along the craniospinal axis. In the sacral region, they are typically located within the sacral canal or ventral to the sacrum in the presacral space. They are thought to occur because of failure of the surface ectoderm to cleave from the developing neural tube during embryogenesis. As a result, dermoid cysts sometimes maintain a persistent communication with the skin via an epithelium-lined tract. The tract may extend to the intraspinal neural elements, providing an avenue for the ingress of bacteria, leading to recurrent bouts of bacterial meningitis. A skin defect, representing the superficial stoma of the tract, may be visible. A dimple or sinus located in the postcoccygeal region usually terminates in the coccyx and is of little significance; however, higher lesions are more likely to be associated with a deep tract and with spina bifida occulta.12 Any patient with lower back pain and fever or episodes of meningitis should undergo a detailed search for a dermal sinus tract.

On gross examination, dermoid cysts appear as welldefined, lobulated masses that contain a viscous fluid made up of sebaceous fluid, epithelial debris, and occasionally hair. The cyst wall is composed of stratified squamous epithelium and dermal appendages, including sweat glands, hair follicles, and sebaceous glands. Repeated infections can disrupt this histologic pattern.13 Dermoid cysts grow by epithelial desquamation and glandular secretion.

The location of the dermoid cyst, whether intraspinal or presacral, largely determines its clinical presentation, radiographic features, and surgical treatment. The presacral variety is asymptomatic in up to 60% of cases and is often discovered during routine gynecologic evaluation. 14 Patients may present with lower back pain and fever secondary to abscess formation or give a history of recurrent purulent drainage though a perianal sinus or a fistulous communication with the rectum. A mass may be found on palpation of the posterior wall of the rectum. Neurologic function is usually normal. Radiographically, very large presacral dermoid cysts may erode the anterior aspect of the sacrum. Dermoid cysts are generally very low density masses on CT. They appear hyperintense on T1- and hypointense on T2- weighted MRIs.15 The treatment of patients with presacral dermoid cysts is surgical removal, generally via a presacral perineal approach.

Intraspinal dermoid cysts are less frequently asymptomatic, often presenting before the age of 10 years.11 Patients may have a history of recurrent bouts of bacterial meningitis. Neurologic dysfunction may occur secondary to cauda equina compression or, in cases in which the cyst is adherent to the filum terminale, a tethered cord syndrome. The absence of a dermal sinus tract on examination does not preclude the presence of a dermoid cyst. A posterior occult spina bifida will be found on plain x-rays in about two thirds of patients.11 Many patients also have bony erosion of the posterior sacral elements on CT. MRI is important in evaluating the rostral extent of the mass, to determine whether or not there is intradural extension, to evaluate for the presence of a dermal sinus tract and to rule out other types of associated occult spinal dysraphism. Treatment generally involves a laminectomy and complete resection of the cyst, including the sinus tract, if present. Spillage of the contents of the cyst should be avoided because this material can invoke a chemical meningitis.

Other Sacrococcygeal Inclusion Tumors

The epidermoid cyst is a rarer inclusion tumor in the sacrococcygeal region than the dermoid cyst; both are referred to as dermoids. In epidermoids, the cyst wall does not contain any dermal elements. Retrorectal tailgut cysts are rare presacral, mucus-secreting lesions that are thought to develop from remnants of the postanal gut, which is the most caudal portion of the hindgut during the early stages of development when the embryo still possesses a tail.12,16 The presence of cuboidal or columnar epithelium helps distinguish tailgut cysts from dermoid or epidermoid cysts. A range of other enteric malformations, including hindgut malformations and enteric duplication cysts, may occur as presacral, postsacral, or combined lesions.12 Enteric duplication cysts differ from tailgut cysts by the prominence of a well-formed smooth muscle layer in the cyst wall.17

Anterior Sacral Meningoceles

Anterior sacral meningocele is a rare cystic meningeal herniation that extends ventrally into the pelvis through a bony sacral defect. The cyst is filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and is in direct communication with the spinal subarachnoid space. Most patients have a normal spinal cord and cauda equina. There is a 9:1 female-to-male predominance. 18 The initial diagnosis is typically made in women during the reproductive years. Chronic constipation, abdominal mass or fullness, urinary obstruction, and obstetrical problems are common presenting symptoms.12 Most patients do not have neurologic symptoms or signs. A classic “scimitar-shaped” sacral defect may be seen on plain x-ray films.18 Myelography demonstrates communication of the sac with the spinal subarachnoid space. MRI shows the relationship of the meningocele to the other pelvic structures and may reveal other associated malformations, such as inclusion cysts, teratomas, and lipomas.19

Cyst aspiration or drainage should never be performed from any route because of the risk of meningitis. The treatment is obliteration of the communication between the spinal subarachnoid space and the meningocele, usually by laminectomy and transdural ligation of the neck of the meningocele. Although it is rare for nerve roots to herniate into the sac, inspection of the contents of the meningocele is recommended; any functional neural elements should be preserved by plicating the neck.20 Following closure of the neck, the meningocele may be aspirated. Excision of the sac is not required. When a large anterior sacral meningocele is diagnosed during pregnancy, elective delivery by cesarean section once the fetus has reached pulmonary maturity is recommended because these masses are associated with a high mortality rate at labor due to pelvic obstruction, cyst rupture, and infection.21

Occult Intrasacral Meningoceles

Occult intrasacral meningocele is a dilated intrasacral extension of the thecal sac beyond the normal termination at S2. Like the anterior sacral meningocele, these lesions do not typically contain any neural elements.22 CSF flows freely from the tip of the subarachnoid space into the meningocele. The sac is composed of fibrous tissue resembling dura and is usually lined by arachnoid. The sacral spinal canal is often enlarged or eroded. A dysraphic etiology is supported by an association with spina bifida and tethered cord syndrome.23

Intrasacral meningoceles can compress the cauda equina, producing a slowly progressive neurologic deficit. More often, patients present with lower back or buttock pain. The treatment in symptomatic patients is sacral laminectomy, separation of the sac from the anteriorly displaced nerve roots and ligation or excision of the sac. If the meningocele contains nerve roots or the roots are adherent, the narrow communication between the sac and the subarachnoid space can be enlarged in an attempt to eliminate the ball-valve mechanism.

Perineural (Tarlov’s) Cysts

The perineural cyst, described by Tarlov,24 is an outpouching of the perineural space along the extradural posterior sacral or coccygeal nerve roots. These cysts, which are often multiple, are thought to cause lower back pain and sciatica in some cases.25 Pressure erosion from perineural cysts and other bony defects in the sacrum may predispose to sacral insufficiency fractures.26

Teratomas

A teratoma is a lesion containing tissue from all three germ layers, represented by either well-differentiated or immature elements. Teratomas of the spine are divided by location into two groups: teratomas of the spinal canal and sacrococcygeal teratomas. Sacrococcygeal teratomas are the most common childhood germ cell tumor, with an incidence of one per 40,000 live births.27 These lesions can occur in adults;28 however, adult patients often present with symptoms or a mass noted since childhood.29 Sacrococcygeal teratomas are more common in females and are usually present at birth as a large mass protruding from below the coccyx. Presacral and sometimes combined pre- and postsacral (“dumbbell- shaped”) lesions also occur. About 30% of sacrococcygeal teratomas are malignant, and up to 15% will have already metastasized to lung, liver, or bone by the time of diagnosis.30

Although the distinction between benign and malignant teratoma is ultimately made by histologic examination, several clinical features can help in identifying malignant tumors preoperatively.30 Malignant teratomas most often arise in the presacral space, whereas those located below the pelvic floor distal to the coccyx are usually benign. There is a higher rate of malignancy among teratomas presenting after the age of 2 months, possibly due to malignant degeneration of previously benign lesions. Patients with malignant teratomas often have bladder or bowel dysfunction and evidence of compression of pelvic and lymphatic structures, whereas most patients with benign tumors do not have any functional abnormalities. Radiologically, the majority of benign teratomas are cystic and there is usually no bone destruction. Malignant teratomas, on the other hand, often exhibit locally invasive growth into pelvic structures. The presence of focal calcifications or teeth in 20 to 50% of cases may assist in the diagnosis of teratoma, but does not necessarily imply a benign nature, because calcification is occasionally seen in malignant teratoma.12 Serum α-fetoprotein levels are often elevated in untreated malignant teratoma.12

Patients with sacrococcygeal teratomas often have other associated sacrococcygeal abnormalities, complicating the diagnosis. The Currarino triad31 refers to the rare association of a congenital anorectal stenosis (or other type of low anorectal malformation), an anterior sacral bony defect or abnormality, and a presacral mass (which may include a teratoma, meningocele, dermoid cyst, or enteric cyst).32

The main question arising from the histology of teratomas is the prognostic significance of immature tissues. In infants, the presence of fetal tissues does not indicate malignancy.12 The major histologic criterion of malignancy is the presence of foci of “yolk sac tumor,” variously termed endodermal sinus tumor, embryonal carcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, or teratocarcinoma.12

Benign teratomas have a favorable prognosis following radical en bloc resection, including removal of the coccyx. In a multicenter review, recurrent disease was reported in nine of 80 patients (11%) with mature teratoma that was thought to have been completely excised. 33 In patients with malignant but nonmetastatic lesions, a complete en bloc resection may be adequate therapy. Survival for malignant lesions with metastases is excellent, with surgical resection combined with modern chemotherapy.33 The role of radiotherapy for these tumors is limited.34

Hamartomas

Congenital spinal hamartomas are a rare but distinct clinical entity, defined as tumors of well-differentiated mature elements situated in an abnormal location. Unlike teratomas, they do not contain tissue from all three germ layers. Hamartomas also do not have the malignant potential of teratomas. They are an infrequent but important consideration in the differential diagnosis of a congenital dorsal midline mass and are occasionally found in the sacrococcygeal region. Management consists of surgical excision to prevent neurologic damage secondary to mass effect or tethering, to prevent infection, and to provide an aesthetic improvement.35

Chordomas

Chordoma is the most common primary bone tumor of the sacrum.10 In the absence of dedifferentiation these tumors are very slow growing but locally aggressive (Fig 25-1). Although metastases are infrequent initially, ~30% of sacrococcygeal chordomas eventually metastasize. 2 Sacral chordomas occur almost twice as frequently in men compared with women and are uncommon in individuals less than 40 years of age.36 The most common presenting symptom is pain in the lower back or sciatic region. Chordomas may reach a very large size before constipation (from rectal compression) or lower extremity paresis (due to sacral plexus involvement) occurs. The mean duration of symptoms in one review ranged from 4 to 24 months (mean, 14 months), emphasizing the importance of a high index of suspicion and prompt use of appropriate imaging modalities to achieve an early diagnosis.37

Chordomas are considered congenital in origin because the microscopic appearance of vacuolated “physaliphorous” cells resembles that seen in notochordal remnants. The midline location of these tumors also relates to this proposed etiology. Sacrococcygeal chordomas usually involve the fourth and fifth sacral vertebrae.5 Large tumors protrude anteriorly into the pelvis, but do not invade the pelvic structures because growth is limited by the presacral fascia.

The usual CT appearance consists of lytic bone destruction in addition to a disproportionately large soft tissue mass. Calcification is present in 30 to 70% of cases.6 On T1-weighted MRI, chordomas are iso- or slightly hypointense compared with muscle; they are hyperintense on T2-weighted images.6 Unlike most bone tumors, chordomas may show reduced uptake or normal distribution of isotope on bone scan.38

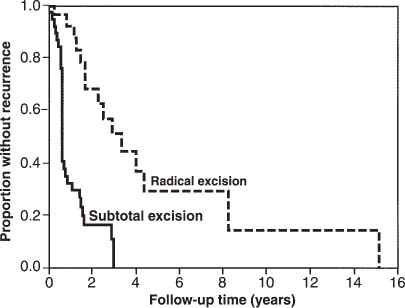

Radical resection, whenever possible, is the treatment of choice for sacral chordomas. The extent of surgical resection has been found to play a major role in determining the length of disease-free survival (Fig 25-2).2,37,39,40 Although a distinct capsule is often seen within the soft tissues, a radical wide posterior margin of the gluteal muscles should be employed to reduce the risk of local recurrence.41 The margins within bone are often indistinct. Surgical resection should extend at least one whole sacral segment beyond the area of gross disease if the advancing edge of the tumor is to be included in an en bloc resection.

Chemotherapy has been proven to be of no value in the management of these tumors. Many reports have failed to show any significant benefit from conventional or hyperfractionated radiation therapy after subtotal tumor excision;40,42,43 however others have found that subtotal excision plus radiotherapy was superior to subtotal excision alone in lengthening the disease-free survival2,44 (Fig 25-2). The place of newer techniques of radiation delivery, such as fast neutron therapy,45 is yet to be determined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree