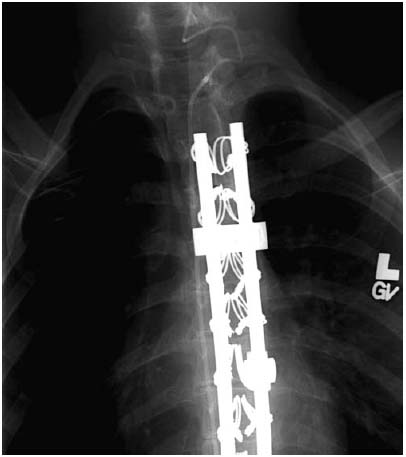

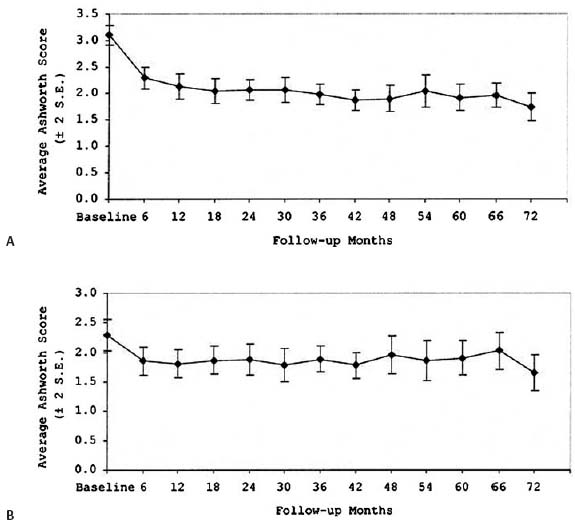

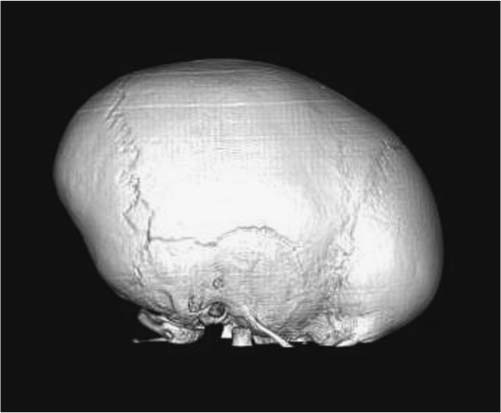

9 Scaphocephaly/Sagittal Synostosis Since Lane performed the first sagittal synostectomy in 1892, surgeons have sought to correct the cosmetic deformity caused by sagittal synostosis and prevent any of its possible deleterious effects.1 Efforts have ranged from a simple strip craniectomy advocated by Shillito and Matson2and Hunter and Rudd,3 to the more extensive procedure pioneered by Jane,4 to extensive cranial vault remodeling popularized in the 1990s by Marsh et al,5 Boop et al,6Penslar et al,7 Maugans et al,8 and others with varying degrees of success.9 After decades of research, it is now apparent that there may not be a single “gold standard” for sagittal synostosis. Rather, different procedures are indicated based on the age of presentation and the degree of scaphocephaly. Although scaphocephaly is present in ~2 of every 10,000 live births,10 most infants do not present for neuro-surgical evaluation until they are an average of 5 months, which may exclude simple suturectomies as they often do not address the long-term scaphocephalic shape and suture recrudescence.6 However, as the awareness of craniosynostosis increases in the community, the average age at presentation may decrease. Younger age at presentation may allow for less invasive procedures on relatively younger infants, thereby lowering intraoperative blood loss and potential morbidity while still improving aesthetics. Cranial vault remodeling (CVR) has several disadvantages when compared with a simple strip suturectomy. It is associated with more extensive blood loss and exposes a much larger surface area of the brain over a longer period of time, raising the risk of morbidity and mortality.11,12 In addition, CVR requires a joint effort between neurosurgeons and plastic surgeons, the use of absorbable plates, and a longer hospital stay, which drastically raises the expense of the procedure.13 Given these disadvantages, it would be beneficial for a select group of infants younger than 3 months of age with minimal deformity to undergo a less invasive approach. The diagnosis of scaphocephaly is generally made from the physical examination. According to Virchow’s law, bony direction ceases in the direction perpendicular to the sagittal suture and compensates in the opposite direction. As a result, these infants usually have a long, narrow head with a prominent bony ridge along the sagittal suture. Predictable compensatory growth occurs at adjacent sutures and can affect the shape of the entire skull.4 As a result, frontal bossing or an occipital prominence may also be noted. Plain radiographs are useful for demonstrating fused sutures. In addition, a three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan can provide further proof of suture fusion and can also identify any underlying brain abnormalities.14 Surgical treatment for craniosynostosis is generally preferred within the first year of life, when the infant’s skull is malleable and the nonpathologic sutures have not yet fused.15 Although craniosynostosis may be detected by the third trimester on fetal ultrasound,16 most patients do not typically present for evaluation until they are several months old. Typically, the first 2 months of life involve rapid growth of the cranial vault, accompanied by nearly doubling of brain mass by the first 6 months of life.17 Surgery during this period has many challenges, but it also may benefit from the intracranial dynamics. Although a simple strip craniectomy poses a risk of rapid suture recrudescence, early suture release within the first few months of life can take advantage of rapid brain growth and development to aid in natural CVR with or without the aid of external devices.18 Surgeons therefore must weigh the ability of the infant to tolerate the surgery, which increases with age, against the changing malleability of the skull, which favors early surgery. As such, a simple strip craniectomy is ideally performed in infants younger than 3 months with mild scaphocephaly without significant frontal bossing or occipital knobs.19 For older infants between 6 and 12 months of age or those with more significant deformities, cranial vault reconstruction may be more appropriate. In addition, infants who have undergone a simple strip suturectomy should be followed with serial exams and head circumferences to assess whether they will need further CVR in the future.20 The patient is placed in the supine position with the head resting in a padded suboccipital support (Fig. 9.1). The infant is then prepped and draped widely. Local anesthetic with epinephrine is used to decrease postoperative pain and minimize incisional bleeding from the scalp. A midline skin incision is made from 1 to 2 cm anterior to the anterior fontanelle to 1 to 2 cm posterior to the lambda (Fig. 9.2A). This incision may be elongated for patients with occipital prominence. Skin clips are used to reduce bleeding from the scalp edges. The scalp is then reflected bilaterally, dissecting through the loose areolar plane of the scalp, above the pericranium, as its preservation reduces blood loss. When the anterior fontanelle is open, a curet is used to separate the dura underlying the fontanelle from the overlying pericranium. Two bur holes are then made on either side of the sagittal suture just anterior to the lambdoid sutures. A craniotome is used to connect these bur holes to the edges of the anterior fontanelle (Fig. 9.2B). Great care is taken when removing the bone overlying the sagittal sinus, with either Kerrison punches or rongeurs. The width of the suturectomy is based on surgeon preference, weighing the risk of suture recrudescence against the need for future cranioplasty if significant bony regrowth does not occur. Venous bleeding is controlled with the use of cottonoid patties, bipolar electrocautery, and surgical hemostatic matrix. Following copious irrigation, the incision is then closed with resorbable sutures in the galea and a running resorbable suture through the scalp (Fig. 9.2C). We have not endorsed the use of drains. Fig. 9.1 Positioning of the patient with sagittal synostosis. Fig. 9.2 Operative technique for early strip craniectomy. (A) Exposure of the sagittal suture. (B) Craniotomy. (C) Closure. Patients are generally extubated immediately following the case and cared for in the pediatric intensive care unit until they have achieved hemodynamic stabilization. We trans-fuse for hematocrits < 22, platelets < 100, or an international normalized ratio (INR) > 1.3. Scheduled alternating ibuprofen and Tylenol is used for pain control. The entire hospital stay rarely exceeds 4 days. In addition to a simple strip craniectomy, many devices exist on the market today to prevent restenosis of the excised sutures and aid in correction of the scaphocephalic shape. Although the strip craniectomy alone often corrects the biparietal dimension, it can fail in the correction of the anteroposterior elongation. This is where additional operative techniques and external devices may play a critical role. Silastic and other plastic strips have been used to impede regrowth of bone at the suture site. Although effective at preventing suture recrudescence, their use has fallen out of favor in an effort to avoid permanent implants. Another effort to reduce bony regrowth involved applying Zecker solution to the underlying dura. However, its predisposition to lowering the seizure threshold has reduced its usage. New research has focused on the use of Noggin, a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) inhibitor, to prevent postoperative resynostosis in infants with craniosynostosis.21 Preliminary data on rabbits are promising, but further clinical correlates are needed. For centuries, various civilizations have demonstrated the effectiveness of external pressure on molding cranial shape. Skull-molding caps were originally designed over 30 years ago to provide additional cranial molding after surgery. These devices have been demonstrated to result in greatly improved cranial shapes than those created by surgery alone.22 Although surgical correction is still the mainstay of treatment for craniosynostosis, modern molding helmet therapy continues to be a valuable tool in promoting normal growth patterns postoperatively, even after a helmeting course is completed.23,24 Patients typically wear a series of two helmets over the course of 1 to 2 years to promote gradual remodeling over time. It is unknown whether helmeting alone would be effective for sagittal synostosis, as this has not been studied secondary to the lack of funding for correction of scaphocephaly in the absence of surgical repair. Since the late 1990’s, Lauritzen has pioneered the use of internal springs to correct nonsyndromic sagittal suture synostosis. His studies of strip craniectomy combined with placement of internal springs at an average age of 3 to 4 months resulted in efficacious treatment of sagittal synostosis.25 Further studies comparing spring-assisted cranial remodeling with external helmeting would be advantageous. Although substantial research has been conducted to elucidate any impact of craniosynostosis on long-term cognitive development, no clear association has been made. Certainly, learning disabilities do exist in this population of patients; however, the frequency does not seem to be affected by surgical intervention.26,27 The more commonly reported measure of surgical outcomes for sagittal synostosis is the cephalic index (CI), an easily calculated ratio of width to length based on CT scans. However, this is an imperfect grading scale, as it may fail to account for “hourglass” bitemporal distortion of severe frontal or occipital bossing. This leaves us with a photographic aesthetics end point, which is more or less subjective, often based on the child’s and the parents’ perspective as they age.28,29 A simple strip craniectomy with or without an external molding device is an option for the correction of nonsyndromic, isolated sagittal synostosis without frontal bossing or an occipital prominence in infants younger than 3 months of age. Newer techniques involving retrievable springs may provide a reasonable alternative to helmeting. For older infants or those exhibiting signs of more extensive suture fusion, CVR would be indicated. Sagittal synostosis, the premature fusion of the sagittal suture, is the most common form of craniosynostosis. It is generally not recognized until scaphocephaly becomes clinically observable. Sagittal synostosis accounts for 40 to 60% of single-suture synostoses. It is generally accepted that the incidence of scaphocephaly ranges from 1 in 2000 to 1 in 5000 live births.30 The skull deformity resulting from premature closure of the sagittal suture is predictable. Transverse growth of the skull will be restricted, and the calvarium will be long anteroposteriorly and narrow in the tempoparietal region with ridges at the site of the fused suture (Fig. 9.3). Schmelzer et al31 identified four predictable patterns of calvarial dysmorphology in patients with scaphocephaly: bifrontal bossing, bitemporal retrusion, coronal constriction, and occipital protuberance (Fig. 9.4). The etymology of the word scaphocephaly indicates this clinical appearance (from the Greek scaphos, meaning “boat,” and kephaly, meaning “head”). Additional changes such as frontal and occipital bossing will vary among individuals. Signs of scaphocephaly will usually present between 1 and 4 months of age and should be identified by an astute pediatrician. The etiopathogenesis of primary scaphocephaly remains mainly unknown. Multiple theories have been offered. Virchow, in 1851, initially proposed that the suture was the primary abnormality and was translated to the cranial base. More than 100 years later, Moss, in 1955, theorized that tension at the cranial base was translated to the cranial vault suture. It is now relatively well accepted that misregulation in apoptosis might be related to early maturation of cranial sutures.32 Furthermore, environmental and genetic factors play a role in the pathogenesis of scaphocephaly. As shown by the work of Lajeunie et al,33 a genetic component is supported by the higher risk in monozygotic twins, whereas the presence of an environmental component is reinforced by the high rate of twinning, normal monozygotic/dizygotic twin ratio, and a < 100% concordance rate in monozygotic twins. Fig. 9.3 Three-dimensional computed tomography (CT) scan showing the fused sagittal suture and increased length-to-width ratio of the calvarium. Fig. 9.4 Three-dimensional CT scan of a patient with scaphocephaly showing the prominent occipital protuberance. Clinical examination will often be sufficient to develop suspicion of isolated sagittal synostosis. Some centers routinely request CT scans to confirm their clinical diagnosis. Such studies not only allow confirmation of a clinical diagnosis but can also be used for presurgical planning and will provide another tool to follow these patients and objectively evaluate outcomes. Nevertheless, this represents radiation that might be construed as unnecessary by some. In fact, the work of Agrawal et al34 elegantly showed that diagnosis and treatment planning of isolated sagittal synostosis can be reliably made clinically. The CI represented by the maximal transverse width (euryon–euryon) divided by the maximum anteroposterior length (glabella–opisthocranium) is reduced.35 It is usually calculated using a digital caliper from a CT study of the patient’s calvarium. Normal head shape has an average CI of 76 to 78%. Classically, infants with isolated sagittal craniosynostosis will have a CI from 60 to 67%. These measurements can also be performed clinically, but the soft tissue envelope must be taken into consideration. In the past, several radiologic examinations were used to diagnose and treat the synostosis. Plain radiographs are used to show sclerosis and occasionally show “thumb printing” as a sign of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). These are also of historic significance, because of the widespread and easy access to CT scans. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is of limited use in the bony anatomy and is mostly used to evaluate for subtle posterior fossa brain parenchyma deformities, such as Chiari malformations. Treatment goals of scaphocephaly are to increase the potential space and reorient the vectors of cerebral growths, restore the cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, and improve the cosmetic appearance of the skull by reshaping the cranial vault. The latter is performed by correcting the deformational changes and excising the fused suture. When diagnosed early (before 6 months of age), this can be done using sagittal strip craniectomy and outfracture of the parietal bone. In cases where the patient presents between 6 and 12 months of age, subtotal calvarectomy with vault remodeling is typically performed and will be discussed here. Late presentation (age 12 months and older) represents a more complex problem, as represented by more severe clinical findings. Weinzweig et al36 reviewed their experience in a patient population. Total CVR is often required to address the fronto-orbital deformity. This can be performed in a single- or two-stage approach. When a staged procedure is planned, the fronto-orbital deformity is addressed at the same time as the anterior two thirds of the calvarium in the initial stage. Staging a procedure will decrease the operative time and the blood loss. Despite refinements in the management of delayed presentation, early diagnosis remains the best way of simplifying and directing the management of isolated sagittal suture synostosis. General guidelines for safe management of the craniofacial patient rely heavily on communication among all parties involved. The anesthesiologist sees the patient preoperatively and assesses the overall health of the child and his or her fitness to receive the operation outlined. Risks of large volumes of blood loss as well as the potential for air emboli make it necessary in all but the most minor intracranial procedure to establish arterial lines and central venous access and to place a precordial Doppler, as well as an end-tidal CO2 monitor. Surgical teams place a Foley catheter for urine measurement. The patient is positioned to pad all bony prominences. Typically, patients are positioned supine for a suturectomy. The patient who needs a posterior expansion is placed in a Mayfield horseshoe that has been triple padded with cotton to prevent facial pressure sores. Because the eyes are the most sensitive structure on the face, both the anesthesiologist and the surgeon must confirm that they are covered or have no pressure on them. Prior to this, the eyes are lubricated and covered in Tegaderm mesh dressing. Anterior advancements are done in the supine position, on a Mayfield horseshoe headrest. Since the earliest days of treatment, surgical techniques have been described to correct this pediatric deformity. They were first described for sagittal synostosis mainly because it is the most often detected synostosis. These techniques were aimed at correcting the deformity by re-creating what was not present in nature, the sagittal suture. These techniques were mainly employed when the surgery was felt to be safe and have been used on younger and younger patients to yield better results. Although suturectomy is the mainstay in early treatment, it relies totally on the growth of the head to correct the deformity. These techniques have been augmented by the use of helmet therapy that had traditionally been used with nonsynosotic plagiocephalic children. Newer techniques, such as endoscopic repair, are pushing the envelope and allowing more osteotomies for reshaping that were not previously possible. They all, however, rely on the growth of the head and the helmet to reshape the patient postoperatively. Fig. 9.5 Narrow biparietal distance with pseudoturricephaly. Because the main risks of mortality in surgery are related to sagittal sinus injury, I do not believe that closed/endoscopic repairs are necessarily safer than other repairs as has been reported.37 The main advantage I see to endoscopic repair is the fact that blood transfusions are not needed. Because of this, I am an advocate for earlier surgery whenever possible and minimal surgery when there is significant growth left and the family is committed to using a helmet to recontour the head. However, I treat most of my cases as standard open approaches, mainly because parents are not always willing to commit to the use of a helmet. It is inconvenient, time-consuming, and cannot be used to overcompensate the head to take into account future growth.

Early Strip Craniectomy

Diagnosis

Operative Technique

Patient Selection

Operative Procedure

Postoperative Treatment

Adjuvant Treatment

Bone Growth Inhibitors

Helmets

Springs

Outcomes

Conclusion

Late Craniofacial Reconstruction

Diagnosis

Radiology

Treatment Planning

Surgical Management

Preoperative Management

Surgical Techniques

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree