33 Sciatic Neuropathy

Anatomy

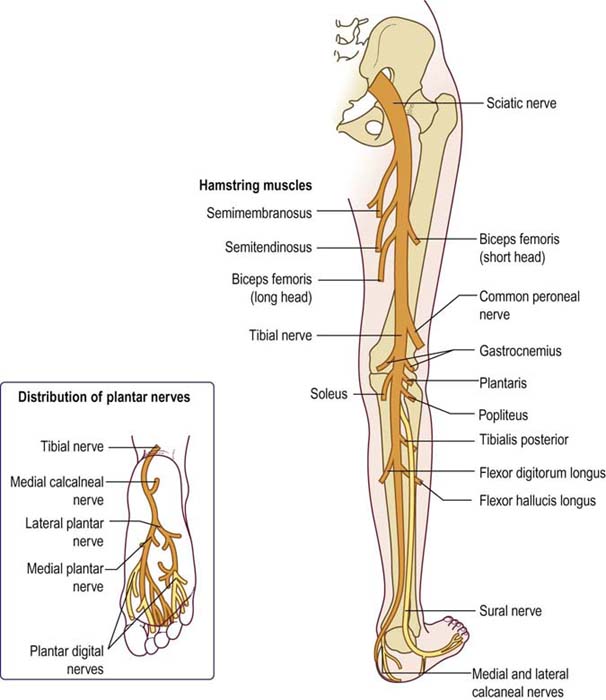

The sciatic nerve is derived from the L4–S3 roots, carrying fibers that eventually will become the tibial and common peroneal nerves. It leaves the pelvis through the sciatic notch (greater sciatic foramen) under the piriformis muscle accompanied by the other branches of the lumbosacral plexus (inferior and superior gluteal nerves and posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh). In some individuals, fibers destined to become the common peroneal nerve run through the piriformis muscle before joining the sciatic nerve. Covered by the gluteus maximus, the sciatic nerve next runs medial and posterior to the hip joint between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter of the femur (Figure 33–1). The knee flexors, including the medial hamstrings (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) and lateral hamstrings (long and short heads of the biceps femoris), and the lateral division of the adductor magnus are all supplied by the sciatic nerve.

FIGURE 33–1 Sciatic nerve anatomy.

(From Haymaker, W., Woodhall, B., 1953. Peripheral nerve injuries. WB Saunders, Philadelphia. with permission.)

Clinical

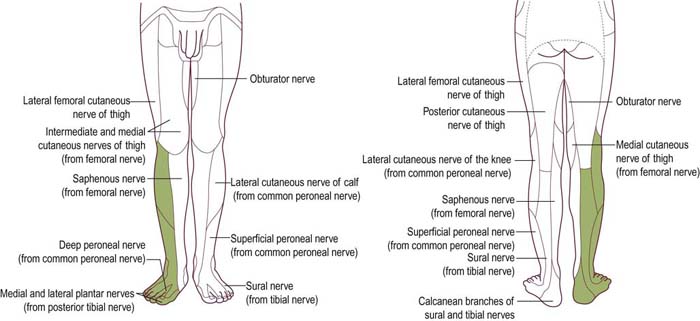

Sciatic neuropathies caused by trauma, injection, infarction, or compression present acutely. Otherwise, most sciatic neuropathies present in a progressive, subacute fashion. Patients with a complete sciatic neuropathy have paralysis of knee flexion and all movements about the ankle and toes. Sensation is lost in several areas (Figure 33–2), including the lateral knee (lateral cutaneous nerve of the knee), lateral calf (superficial peroneal nerve), dorsum of the foot (superficial peroneal nerve), web space of the great toe (deep peroneal nerve), posterior calf and lateral foot (sural nerve), and sole of the foot (distal tibial nerve). Pain may be perceived in the proximal thigh, radiating posteriorly and laterally into the leg, but it usually does not affect the back. The ankle reflex is depressed or absent on the involved side.

FIGURE 33–2 Sensory loss in sciatic neuropathy (in green).

(Adapted from Haymaker, W., Woodhall, B., 1953. Peripheral nerve injuries. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, with permission.)

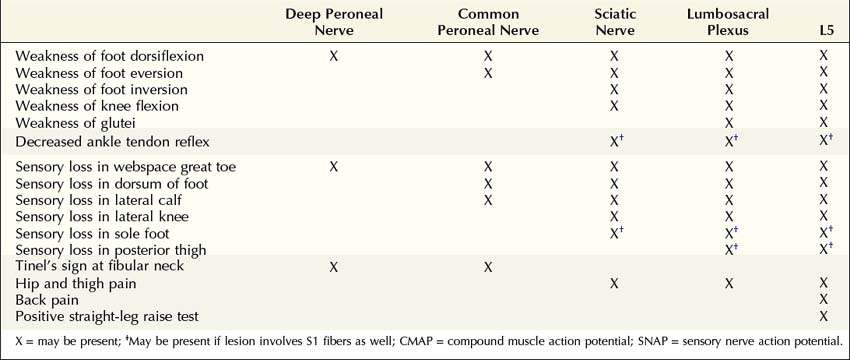

This complete deficit is seen only in severe lesions or late in the course of sciatic neuropathy. Initially, the clinical presentation most often mimics peroneal neuropathy. It has long been recognized that the peroneal fibers are preferentially affected in most sciatic nerve lesions. Thus, it is not unusual for a patient with sciatic neuropathy to present with a footdrop and sensory disturbance over the dorsum of the foot and lateral calf. Indeed, early sciatic nerve lesions may be nearly impossible to differentiate clinically from peroneal nerve lesions at the fibular neck (Table 33–1).

Etiology

Sciatic neuropathy is distinctly uncommon and is associated with a limited differential diagnosis (Box 33–1). As the sciatic nerve runs posterior to the hip joint, one of the most common presentations occurs following hip or femur fracture (especially posterior dislocation) or as a complication of the subsequent surgery to repair the fracture. As a complication of surgery, sciatic neuropathy may occur due to retraction or stretch, as well as a result of methylmethacrylate cement forming spurs and then eroding into the nerve months to years later, which has been well documented in several case reports.

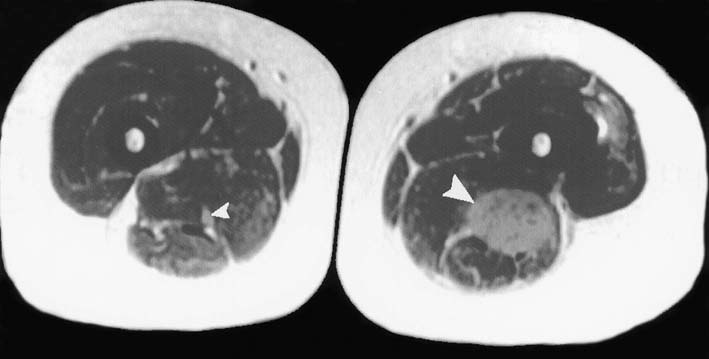

Another common cause of sciatic neuropathy is tumor (neurofibroma, schwannoma, neurofibrosarcoma, lipoma, and lymphoma). Tumors affecting the sciatic nerve usually can be imaged quite well as a mass lesion on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning (Figure 33–3). Other rare mass lesions also may affect the sciatic nerve. An enlarged Baker’s cyst in the popliteal fossa may compress the distal sciatic nerve as it bifurcates into the tibial and common peroneal nerves. Several unusual vascular abnormalities, including aneurysms of the inferior gluteal, iliac, or persistent sciatic arteries and arteriovenous malformations near the piriformis muscle, have been associated with sciatic neuropathy.

FIGURE 33–3 Mass lesion of the sciatic nerve.

(Adapted from Preston, D.C., Shapiro, B.E., 2001. Lymphoma of the sciatic nerve. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2, 227–228.)

Disorders that result in a mononeuritis multiplex syndrome (see Chapter 26) may affect the sciatic nerve. For example, vasculitic neuropathy commonly results in infarction of the sciatic nerve in the proximal thigh, which is a watershed area for nerve ischemia. The neuropathy often is acute and begins with prominent pain. Until additional nerve lesions develop, recognition of the underlying mononeuritis multiplex pattern is difficult or impossible.

Piriformis Syndrome

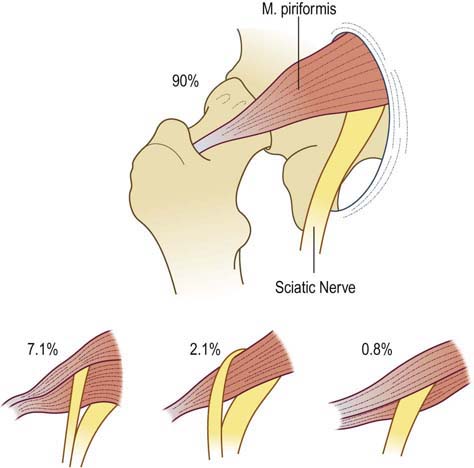

As the sciatic nerve leaves the pelvis, it runs under or through the piriformis muscle (Figure 33–4). The piriformis muscle originates from the sacrum, the sciatic notch and the sacrotuberous ligament, and then runs through the greater sciatic foramen to attach to the greater trochanter of the femur. The main action of the piriformis is to externally rotate the hip. When the hip is in a flexed position, it also acts as a partial hip abductor. Theoretically, a hypertrophied piriformis muscle could compress the sciatic nerve (piriformis syndrome), somewhat comparable to compression of the median nerve by the pronator teres muscle in pronator teres syndrome. In the past, many cases of “sciatica” were attributed to piriformis syndrome. However, most, if not all, cases of sciatica are due to lumbosacral radiculopathy and not sciatic neuropathy from piriformis syndrome. Piriformis syndrome is considered by many to be a controversial entity. There are very few reported cases of patients who meet the criteria for definite piriformis syndrome, which include (1) sciatic neuropathy clinically, (2) electrophysiologic evidence of sciatic neuropathy, (3) surgical exploration showing entrapment of the sciatic nerve within a hypertrophied piriformis muscle, and (4) subsequent improvement following surgical decompression.

FIGURE 33–4 Anatomic relationships of the sciatic nerve to the piriformis muscle.

(Adapted from Beaton, L.E., Anson, B.J., 1938. The sciatic nerve and the piriformis muscle: their interrelation as possible cause of coccygodynia. J Bone J Surg 20, 686–688.)

• The Freiberg maneuver: with the patient lying supine, the examiner forcefully internally rotates the leg, stretching the piriformis muscle.

• The Pace maneuver: in the seated position, the patient abducts the hip against resistance, activating the piriformis muscle.

• The Beatty maneuver: lying on their side, the patient abducts the hip, activating the piriformis muscle.

• The FAIR (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) maneuver: with the patient lying supine, the examiner passively flexes, adducts, and internally rotates the hip, stretching the piriformis muscle. This maneuver is also reported to be useful in the EDX of piriformis syndrome (see below).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree