Age range

Major causes

Infant

Birth injury, hypoxia/ischemia, congenital malformations, congenital infection

Childhood

Febrile seizures, CNS infection, head trauma, birth injury, idiopathic

Young adult

Head trauma, drugs, withdrawal from alcohol or sedatives, idiopathic

Elderly

Stroke, brain tumor, cardiac arrest with hypoxia, metabolic

Electroencephalogram

An EEG commonly helps to classify the individual’s type of epilepsy (see Chap. 3 on common neurologic tests) . Patients rarely experience a seizure during a routine EEG. However, it can provide confirmation of the presence of abnormal electrical activity, information about the type of seizure disorder, and the location of the seizure focus. On a single routine wake and sleep EEG, only 40 % of epilepsy patients will have an abnormal tracing. The spike is the EEG sign of hypersynchronous activation of a population of neurons that could develop into a seizure. Unfortunately, at least 10 % of epilepsy patients never have an abnormal EEG and 2 % of normal individuals who never experience a seizure will have epileptiform abnormalities on their EEG—limiting both the specificity and sensitivity of this test on its own. Therefore, the routine EEG cannot rule in or rule out epilepsy; thus, the diagnosis of epilepsy remains a clinical one.

Seizure Classification

There are several classifications for types of epilepsy that are based on clinical seizure types and/or EEG findings . Seizures are classified as focal or generalized. Generalized seizures arise within and rapidly engage bilaterally distributed networks. The most common types of generalized seizures are tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizures and absence (petit mal) seizures. Focal seizures originate within networks limited to one hemisphere. Focal seizures can be characterized by common features such as aura, motor involvement, autonomic features, and/or changes in awareness or responsiveness. Focal seizures beginning in one hemisphere can spread to involve the other hemisphere—resulting in a bilateral convulsive seizure. Table 15.2 outlines the clinical features of these seizure types. Properly classifying the type of epilepsy and determining the cause of the seizures allows a better prognosis and enables selection of the best anticonvulsant medication to control the seizures.

Table 15.2

Principal seizure types and their clinical features

Type of seizure | Clinical features |

|---|---|

Generalized seizure | |

Tonic-clonic | Loss of consciousness occurs without warning, a marked increase in all muscle tone (tonic) for about 20–30 s followed by rhythmic (clonic) jerks with a gradual slowing of the rate and abrupt cessation after 20–60 s. The patient is unconscious during and immediately after seizure and slowly recovers over minutes to an hour. Tongue biting and urinary incontinence are common. The patient has no recall of the actual seizure event |

Absence | Rapid onset of unresponsiveness that lasts an average of 10 s. There can be staring or other automatisms (eye blinking or lip movements), an increase or decrease in muscle tone and mild jerks. Recovery is immediate but there is no recall of event. Hyperventilation often precipitates seizure. Childhood onset |

Focal seizure (symptoms will depend on brain area involved in seizure) | |

Aura | Sensory, autonomic, or psychic symptoms that occur at beginning of an observable seizure. Common symptoms include GI upset or a strange smell or taste |

Dyscognitive | Seizure propogates to involve limbic or bilateral structures that alters awareness or consciousness |

Focal Seizure

Introduction

Focal seizures originate in one hemisphere in a group of neurons or in a distributed network of neurons . The clinical manifestations of a focal seizure will be based on the particular area of the hemisphere involved .

Major Clinical Features

An aura is a focal seizure (previously known as a simple partial seizure) consisting of psychic, sensory, or autonomic phenomena that are experienced by the patient. It can signal the start of an observable seizure or be a seizure in and of itself. It is typically not observed, but can be elicited by a careful history. An aura can have many forms depending on the localization of the epileptic activity but common aura descriptions include: A rising or falling sensation in their abdomen, a disgusting smell, or metallic taste.

Other focal seizures can manifest as observable motor phenomena if they involve focal motor pathways. In focal seizures arising from the rolandic area, the patient experiences hand tingling which then progresses to hand movements, arm movements, and then leg movements (known as a jacksonian march). When awareness is altered during a focal seizure, it is called a dyscognitive seizure (previously known as a complex partial seizure)—implying limbic involvement and possibly bilateral involvement as well.

The most common cause of focal dyscognitive seizures in adults is seen in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis. A typical seizure would begin with cessation of verbal activity associated with a motionless stare and without normal response to verbal or visual stimuli. Automatisms may occur that are gestural (picking at objects, repetitive hand washing movements) or oral (lip smacking) and the patient may wander aimlessly. These movements tend to be stereotyped for each patient and occur with most seizures. Purposeful movements or violence is unusual. The ictal event (seizure) lasts for 1–3 min followed by a period of postictal confusion that usually lasts for 5 to 20 min. The patient does not recall events during the dyscognitive seizure. The majority of patients with this epilepsy syndrome (70 %) will have a risk factor that predisposes to epilepsy (e.g., complicated febrile seizures before 4 years of age, encephalitis or trauma).

Focal seizures that occur in succession without return to normal behavior in between events results in focal status epilepticus . This can present as prolonged confused behavior and requires an EEG study for diagnosis.

Major Laboratory Findings

The EEG is often helpful in establishing the diagnosis, particularly when interictal spikes are identified coming from the focal region. Because the temporal lobe and underside of the frontal lobe are distant from EEG electrodes, it is difficult to find spikes in some patients. The use of sleep deprivation and special nasopharyngeal and sphenoidal electrodes may improve diagnostic yield. Magnetoencephalography can also be used to identify interictal discharges.

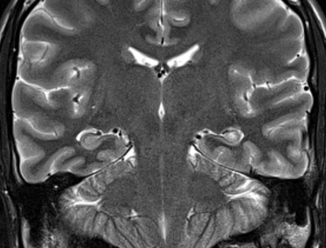

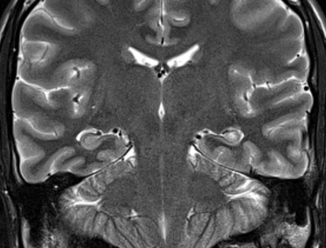

The MRI scan is often performed with special views of the hippocampus to demonstrate mesial temporal sclerosis and also to look for focal pathology elsewhere in the brain (Fig. 15.1). Mesial temporal sclerosis is a scarring of the inner temporal lobe, specifically the hippocampus. It can be the result of head trauma, hypoxia, or infection. In many cases, the scarring is seen on imaging but no clear cause is identified. This scarring is associated with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy as described above.

Fig. 15.1

MRI T2-weighted coronal image of a 25-yearold patient with seizures showing small left hippocampus with bright signal intensity and loss of internal architecture consistent with mesial temporal sclerosis. (Courtesy of Dr. Blaine Hart)

Principles of Management and Prognosis

Management is aimed at controlling the focal seizures and identifying any focal structural lesions that are epileptogenic. (See Table 15.3 for a list of anticonvulsants and their indications). The exact choice of medication will depend on the patient characteristics such as medication interactions. The goal is complete seizure suppression and no medication side effects.

Table 15.3

Major anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsant | Main seizure indications | Likely mechanisms of action | Major side effectsa |

|---|---|---|---|

Carbamazepine and Oxcarbazepine | Focal seizures Generalized convulsive seizures | Inhibits voltage-dependent sodium channels in a voltage- and use-dependent manner | Ataxia Dizziness Diplopia Blood dyscrasia |

Ethosuximide | Absence seizures | Blocks voltage-dependent calcium channels which affect T currents | Headache GI distress Ataxia Blood dyscrasia |

Gabapentin | Focal seizures | Increases synaptic concentrations of GABA | Dizziness Sedation |

Lamotrigine | Generalized seizures Focal seizures | Inhibits voltage-dependent sodium channels in a voltage- and use-dependent manner | Abnormal thinking Ataxia Dizziness Nausea |

Levetiracetam

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|