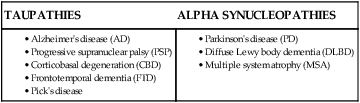

• AD is the most common cause of dementia and can be associated with the irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder and sundowning. In early AD, there is a decrease in stage N3. In late AD, there is a decrease in REM sleep and an increase in the REM latency. • OSA is common in AD patients and, if successfully treated with CPAP, can improve sleep quality and mood as well as slow the rate of cognitive decline. • Donepezil (Aricept), a cholinesterase inhibitor, is used in AD to improve cognition but is often associated with insomnia. Morning dosing is suggested to minimize sleep disturbance. Some studies have suggested that evening doses of rivastigmine and galantamine can improve sleep quality. Cholinesterase inhibitors and cholinergic medications in general tend to increase REM sleep. Rivastigmine has been reported to cause RBD in AD patients. • PSP is characterized by vertical gaze palsy and prominent sleep-maintenance insomnia (worse than in AD) and nocturia. PSP patients have a large reduction in the amount of REM sleep. PSG will often show absence of vertical eye movements during REM sleep. RBD occurs in approximately 13% to 30% of PSP patients. • The sleep of patients with PD is impaired by rigidity, tremor (tends to resolve with sleep onset), dyskinesias, OSA, RBD, and nocturnal hallucinations. Patients with PD can manifest excessive daytime sleepiness even if OSA is not present. Modafinil may be helpful, although the published evidence is conflicting. • PD+ disorders are manifested by parkinsonism (bradykinesia and rigidity), no or decreased response to levodopa, sensitivity to dopamine blockers, and a more rapid course than PD. PD+ disorders include PSP, DLBD, and MSA. • Patients with DLBD have prominent dementia much earlier in the disease course compared with PD. The patients frequently have visual hallucinations and are exquisitely sensitive to dopamine blockers (can develop severe rigidity). The RBD is common in patients with DLBD. • MSA patients have various amounts of striatonigral degeneration (rigidity and bradykinesia), olivopontocerebellar degeneration (cerebellar dysfunction, ataxia, falls), and autonomic dysfunction (erectile dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, bladder dysfunction). The RBD is very common in MSA patients. • Stridor (especially during sleep) is a well-known manifestation of MSA and denotes a poor prognosis. • FFI is a familial autosomal dominant prion disease with progressive insomnia and dementia. PET shows a characteristic absent or very low activity of the thalamus. • There is a high prevalence of sleep apnea in patients who have had a recent stroke. OSA is the most common form of sleep apnea but central sleep apnea (including CSB) can occur. If OSA is present, this is associated with a worse prognosis but CPAP treatment can improve outcomes. Sleep complaints are very common in patients with neurodegenerative disorders (Box 31–1). Some basic knowledge about these disorders is essential for the sleep clinician. The major neurodegenerative disorders are discussed briefly with an emphasis on the effects on sleep. The synucleopathies are chronic and progressive disorders associated with a decline in cognitive, behavioral, and autonomic functions.1,2 The two major categories are taupathies and alpha synucleopathies (Table 31–1). The taupathies are disorders associated with intracellular disposition of abnormally phosphorylated tau (a microtubule-associated protein) usually expressed as neurofibrillary tangles, neurophil threads, and abnormal tau filaments (Pick bodies). Tau proteins are involved in maintaining the cell shape and serve as tracks for axonal transport. The taupathy disorders include Alzheimer’s disease (AD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and Pick’s disease. Alpha synuclein is a protein that helps in the transportation of dopamine-laden vesicles from the cell body to the synapses. The alpha synucleopathies include Parkinson’s disease (PD), diffuse Lewy body dementia (DLBD), and multiple system atrophy (MSA). TABLE 31–1 Dementia is defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by acquired loss of cognitive and emotional abilities severe enough to interfere with daily functioning.1,2 In evaluating any patients with dementia, it is important to rule out treatable causes including medication side effects, hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, depression, and occult obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Pseudodementia of the elderly is due to depression and can be associated with a short rapid eye movement (REM) latency and high REM density. In contrast, patients with AD tend to have a low REM density, long REM latency, and a reduction in the amount of REM sleep. AD is by far the most common cause of dementia with DLBD the next most common (Box 31–2). AD is the most common cause of dementia (>60% of dementias). The diagnosis is one of exclusion. The hallmark is a gradual onset of short-term memory problems. The APO4E genotype is a risk factor for AD. Sleep disturbance worsens in parallel with cognitive dysfunction. Patients with AD suffer from sundowning (Box 31–3), which is defined as nocturnal exacerbation of disruptive behavior or agitation in older patients. This is likely the most common cause of institutionalization in patients with AD. Some of the key points concerning AD are listed in Box 31–4. A number of factors may contribute to sleep disturbance in AD. Degeneration of neurons in a number of areas including the optic nerve, retinal ganglion cells, and suprachiasmatic nucleus may contribute to circadian rhythm disturbances in AD.3–5 These patients may manifest the irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder. Institutional factors can worsen circadian rhythm disorders by decreasing normal zeitgebers (light and activity) and disturbing nocturnal sleep (noise). Poor sleep hygiene including daytime sleeping and decreased physical activity may also impair sleep-wake rhythms. A number of sleep disturbances are present in AD and vary with the course of the illness (Table 31–2). Early in the illness, there is disruption of sleep-wake rhythms, nocturnal awakenings, and decreased stage N3 sleep. Late in the disease course, there is a reduction in REM sleep and increased REM latency as well as excessive daytime sleepiness. Whereas both OSA and medications can contribute to daytime sleepiness in AD patients, sleepiness can occur simply as a manifestation of AD. The disruption of the sleep-wake rhythms manifests itself with large amounts of daytime sleep and often an irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder. As noted previously, there is degeneration of both the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) neurons and the pineal neurons. Recently, a decrease in melatonin MT1 receptors in the SCN has been demonstrated.5 This could be one reason for the poor response to melatonin in AD. A large multicenter trial of melatonin did not show an improvement in elderly patients in group facilities.6 A recent study in AD found that combined bright light and melatonin decreased aggressive behavior and modestly improved sleep efficiency and decreased nocturnal restlessness.7 TABLE 31–2 Sleep Disturbance in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients with AD have reduced cerebral production of choline acetyl transferease, which leads to a decrease in acetylcholine synthesis and impaired cortical cholinergic function. Cholinergic medications (cholinesterase inhibitors) are used to treat AD and are beneficial.9 However, cholinergic medications can cause sleep disturbance. The cholinergic medications used to treat AD include donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Excelone), and galantamine (Razadyne, formerly Reminyl). The dosage of the medications is listed in Appendix 31–1. The cholinesterase inhibitors tend to increase REM sleep. Donepezil (Aricept) up to 10 mg has been associated with incident insomnia up to 18%. Morning dosing of donepezil is recommended to minimize insomnia. Whereas donepezil is a once-a-day medication, rivastigmine is bid to tid and must be titrated up slowly. Rivastigmine and galantamine have more gastrointestinal side effects than donepezil. The sleep of some AD patients may improve with evening doses of galantamine or rivastigmine.10,11 Stahl and coworkers10 reviewed the results of double-blind studies of galantamine and found no higher incidence of sleep side effects than with placebo. Rivastigmine improved sleep complaints in some studies.11,12 Whereas cholinesterase inhibitors have been reported to improve rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) in idiopathic RBD patients, rivastigmine has been reported to cause RBD in patients with AD.13 PSP is characterized by supranuclear extraocular gaze palsy. Manifestations include a pseudobulbar palsy (upper neuron lesion to corticobulbar tract with dysarthria and choking), akinetic rigidity, ataxic gait and falling, limb and axial rigidity, and frontal lobe type dementia. There is a lack of response to dopaminergic medications.1,2 Sleep disturbance will be present in most patients (Box 31–5). Insomnia is the most common complaint (worse than in AD or PD). Patients have an absence or a drastic reduction in REM sleep. Nocturia is a common problem. One study comparing patients with AD and PSP found unsuspected OSA in approximately 50% of both groups.14,15 A high and nearly equal percentage of both groups had REM sleep without atonia. However, clinical RBD was less common in PSP than in PD (7/20 vs. 13/20). If RBD is present in PSG, it presents concomitantly with other findings. In contrast, RBD can occur many years before the onset of PD. CBD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by progressive asymmetrical rigidity, apraxia, and other findings reflecting cortical and basal ganglia dysfunction.1,2 Tau-positive astrocytic threads and oligodendral coiled bodies are noted. Apraxia is characterized by loss of the ability to execute or carry out learned purposeful movements, despite having the desire and the physical ability to perform the movements. It is a disorder of motor planning, which may be acquired or developmental but may not be caused by incoordination. FTD is a type of cortical dementia resembling AD.1,2 It is characterized by insidious onset, early loss of insight, social decline, emotional blunting, relative preservation of perception and memory, perseverance, and echolalia. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows frontal or anterior temporal atrophy. The term parkinsonism is used to refer to a group of manifestations including tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. Parkinsonism is found in both PD and Parkinson Plus (PD+) disorders (Box 31–6).16,17 The PD+ disorders include those characterized by parkinsonism and other manifestations. The PD+ disorders include PSP, DLBD, and MSA. Of note, the brains of PD patients do have Lewy bodies (LBs), but in DLBD, the distribution of LBs is more dense and more diverse. DLBD patients have more prominent dementia than noted in patients with PD. The dementia of DLBD also present much earlier in the course of the disease than the dementia associated with PD. However, there is overlap between PD and DLBD. The PD+ disorders tend to progress more quickly than PD. The typically anti-Parkinson’s medications are either less effective or completely ineffective in PD+ disorders. PD+ patients are also very sensitive to dopamine blockers. 1. Essential tremor—responds to beta blocker, worse on intention, improved with alcohol. 2. Wilson’s disease—a disorder of hereditary copper accumulation. The typical presentation is a young person who has parkinsonian features. Diagnosis is by performing a slit lamp examination for Kayser-Fleischer rings. PD is also called primary parkinsonism or idiopathic PD. The term idiopathic means “no secondary systemic cause.” The etiology of PD is partially understood and, in this sense, is not truly idiopathic. PD is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder associated with a loss of dopaminergic neurons (substantia nigra and other sites). It is characterized by bradykinesia (slowing of physical movement), akinesia (loss of physical movement), rigidity, resting tremor, postural instability, and a good response to levodopa (LD; Box 31–7).16,17 The disorder often starts unilaterally. Movements are slow and reduced facial expressiveness is noted (masklike facies) with infrequent blinking and a monotonous voice. Gait is slow and shuffling with small steps. The tremor in PD is a resting tremor—maximal when limb is at rest and disappearing with voluntary movement and sleep. Secondary symptoms may include cognitive dysfunction and subtle language problems. 1. Essential tremor—Responds to beta blocker, worse on intention, improved with alcohol. 2. PD+ disorders—If cognitive dysfunction occurs early in the disease course of a patient with parkinsonism, DLBD would be suspected. If early postural instability + supranuclear gaze palsy is prominent early, the PSP should be suspected. If autonomic dysfunction is prominent early (erectile dysfunction or syncope), MSA should be suspected. 3. CBD—If CT or MRI shows prominent asymmetry with patchy changes and cortical deficits (apraxia) are prominent, CBD should be suspected. A detailed discussion of the treatment of PD is beyond the scope of this chapter. A very comprehensive and useful discussion of PD is recommended.18 A number of different medications have been used to treat PD (Table 31–3). The usual treatment of PD is with levodopa/carbidopa (LD/CD). CD prevents peripheral metabolism of LD to dopamine, thus reducing side effects and allowing for more LD to reach the central nervous system. Patients may respond to LD/CD but have a number of reported problems. “On times” refers to periods of time when symptoms go away or improve markedly. “Off times” refers to periods of time when symptoms return. “Wearing off time” refers to times when symptoms are under less control. Dyskinesias, manifested by sudden jerky or uncontrolled movements of the limbs and neck, are side effects of LD/CD treatment. Dystonias consisting of abnormal posture or cramps of the extremities or trunk can occur. TABLE 31–3 Medications Used to Treat Parkinson’s Disease

Sleep and Neurologic Disorders

Sleep and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Synucleopathies

TAUPATHIES

ALPHA SYNUCLEOPATHIES

Dementias

Alzheimer’s Disease

Etiology of Sleep Disturbances in AD

Sleep Disturbances in AD

EARLY AD

LATE AD

Disruption of sleep-wake rhythms

Reduction in REM

Increased nocturnal awakenings

Increased REM latency

Decreased stage N3

EDS and daytime napping—not associated with OSA or medications

Treatment of AD

Medication-Induced Insomnia in AD

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Corticobasal Degeneration

Frontotemporal Dementia

Parkinsonism Syndromes (PD, PD+)

Differential Diagnosis of Parkinsonism

Parkinson’s Disease

Differential Diagnosis of PD

Treatment of PD

Dopamine precursor

LD/CD

10/100, 25/100, 25/100

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

of 25/100 tid, titrate up to 25/100 tid.

of 25/100 tid, titrate up to 25/100 tid.