14 Sphenoid Sinus in Skull Base Surgery

Aldo Cassol Stamm, Shirley S.N. Pignatari, Daniel Timperley, Fernando Oto Balieiro, and Fábio Pires Santos

Introduction

Introduction

In recent years, the evolution of imaging methods (mainly computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and endoscopic-assisted transnasal surgery) have contributed to the progress that has been made in the ability to access the skull base via the nasal cavity.

The sphenoid sinuses are the starting point for approaches to the ventral skull base, providing access and orientation to relevant neurovascular structures.1 The privileged location and anatomical relationships in the skull base make it possible to treat transsphenoidally a wide variety of skull base lesions traditionally approached transcranially.

Several transnasal approaches to the skull base have been developed. The appropriate technique depends on the nature, anatomic location, and extent of the lesion, the instrumentation, and the surgeon’s skills and experience.

The endoscopic-assisted transsphenoidal (EAT) approach is a commonly used technique in skull base surgery to reach the clivus, sellar and parasellar region, cavernous sinus, and even the petrous apex.2

Approaches to the Sphenoid Sinuses

Approaches to the Sphenoid Sinuses

Access to the sphenoid sinus is the first step in EAT skull base surgery. Multiple endoscopic approaches have been described, including transseptal, transnasal, transethmoidal, transmaxillary/transpterygoid, and transnasal with removal of the posterior nasal septum. Recently, Stamm and Pignatari2 described a novel endoscopic transseptal/transnasal approach without posterior nasal septal perforation and using a posterior nasal septal mucosal flap based on the sphenopalatine artery, which is discussed further in Chapter 19 (Fig. 14.1). The approach used depends on the anatomic extent of the pathology, and combinations are often used, for example, transnasal on one side combined with transethmoid or transpterygoid on the other. Regardless of the choice of approach, the reconstruction should be considered at this stage of the procedure. If a vascularized flap is required, the flap and its pedicle must be preserved, usually by raising the flap at the start of the procedure and storing it in the nasopharynx or maxillary sinus.3

Transseptal Approach (Fig. 14.2)

This is the classic microscopic neurosurgical approach; however, it can also be performed under endoscopic visualization. Classically an anterior septoplasty incision is performed; alternatively, the approach may be modified to use a posterior septal incision. Mucoperichondrial/periosteal flaps are elevated and the posterior bony septum resected, preserving the superior attachment of the quadrangular cartilage to the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid to prevent nasal saddling. The flaps are elevated over the sphenoid rostrum to identify the natural ostia, and the rostrum is removed using an osteotome, Kerrison rongeurs, or a drill.4 The advantages of this approach are that it is a midline approach and usually avoids septal perforation. However, the exposure is limited compared with that of other approaches, and access is via one nostril, severely limiting the ability to use bimanual or two-surgeon techniques.

Direct Transnasal Approach (Fig. 14.3)

The sphenoid sinus ostium lies medial to the attachment of the superior turbinate. The middle turbinate is usually lateralized and the inferior half of the superior turbinate resected. If access is narrow, the posterior portion of the middle turbinate is also removed. The sphenoid ostium is identified and opened using a Kerrison rongeur. Bilateral access can be obtained by creating a posterior septal window and removal of the sphenoid rostrum.4 This approach has the advantage of being familiar to otorhinolaryngology (ORL) surgeons and simple to perform, providing a wide exposure of the sphenoid when performed bilaterally. The main disadvantages are the potential for nasal synechiae formation and the need for a posterior septal perforation.

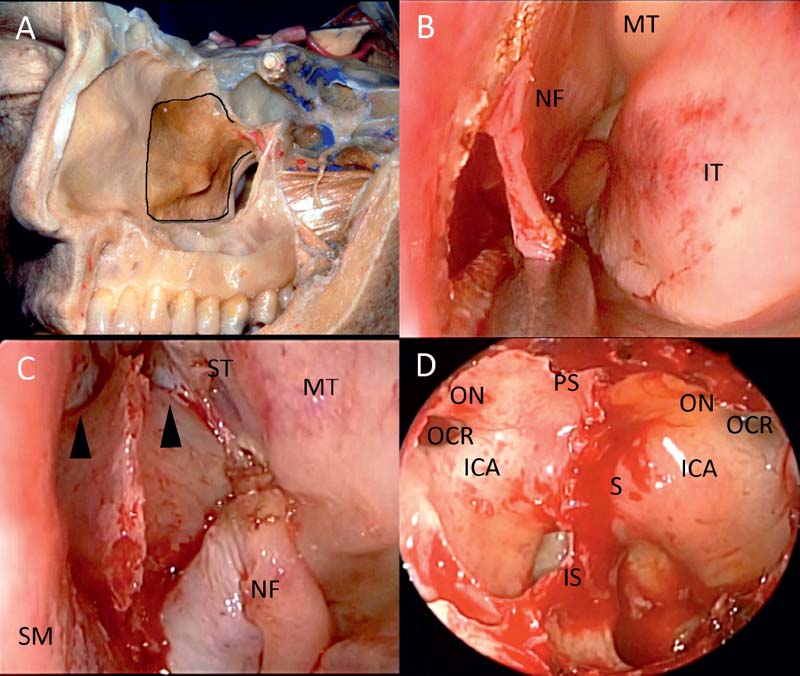

Fig. 14.1 Modified transeptal (binostril) approach. (A) A hemitransfixion incision is made, usually on the right, and a nasoseptal flap will be developed on the contralateral side (outlined). (B) Following elevation of bilateral mucoperichondrial/mucoperiosteal flaps and resection of the posterior bony septum, the nasoseptal flap is developed. Monopolar diathermy is used to outline the flap, and the incisions are completed as necessary using scissors. (C) The flap is placed in the nasopharynx. Access is via the hemitransfixion incision on the right and via the nasal cavity on the right. The sphenoid rostrum and sphenoid sinus ostia are exposed (arrowheads). The sinus is opened as in the standard transeptal approach using an osteotome, Kerrison rongeurs, or a drill. (D) Wide exposure of the sphenoid sinus is obtained. ICA: internal carotid artery; IS: intersinus septum; IT: inferior turbinate; MT: middle turbinate; NF: nasoseptal flap; OCR: opticocarotid recess; ON: optic nerve; PS: planum sphenoidale; S: sella turcica; SM: right septal mucoperiosteum; ST: superior turbinate.

Transethmoidal Approach (Fig. 14.4)

The transethmoidal approach involves resection of the ethmoid sinuses. The middle turbinate is usually partially or completely removed, and a posterior septectomy facilitates binasal access. Uncinectomy, middle meatal antrostomy, and removal of the ethmoid bulla enable identification of the orbital floor, lamina papyracea, and the posterior wall of the maxillary sinus. The ground lamella of the middle turbinate is opened and the superior turbinate identified. Resection of the inferior half of the superior turbinate reveals the sphenoid ostium lying medial to its attachment. The ostium can then be widely opened and the skull base identified. The remaining ethmoid cells are then removed as required.4 The advantage of this approach is the creation of a large cavity, facilitating the movement of instruments and improved lateral access. This approach is more technically demanding and time-consuming than the transseptal or transnasal approaches, although it should be familiar to ORL surgeons. Provided that the mucosa has not been stripped, healing is usually rapid, with little crusting or risk of adhesion formation.

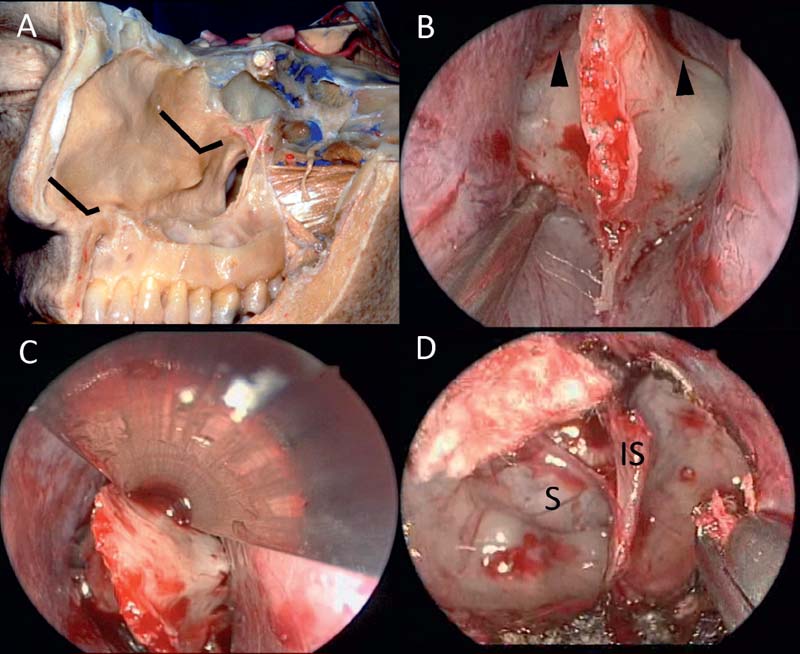

Fig. 14.2 Transseptal approach. (A) Traditionally an anterior septal incision is used; however, the technique may be modified to use a posterior incision. (B) Bilateral mucoperichondrial/mucoperiosteal flaps have been elevated and the posterior bony septum removed to expose the sphenoid rostrum. The flaps are elevated to identify the sphenoid sinus ostia (arrowheads). (C) Bony incisions are made using the osteotome. Vertical incisions are made from the natural ostia through the choanal rim. The vertical incisions are then joined with horizontal incisions inferiorly and superiorly between the ostia. (D) Following removal of the sphenoid rostrum, the sella is visible. The opening may be enlarged using a Kerrison rongeur. IS: intersinus septum; S: sella turcica.

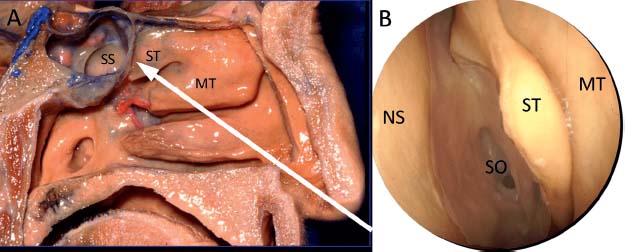

Fig. 14.3 Direct transnasal approach (left). The superior turbinate is lateralized or partially resected to reveal the sphenoid ostium medial and posterior to the superior (or supreme) turbinate. (A) Cadaver dissection of the left nasal cavity demonstrates the trajectory of the direct transnasal approach (arrow). (B) The superior turbinate has been lateralized to reveal the left sphenoid sinus ostium. MT: middle turbinate; NS: nasal septum; SO: sphenoid sinus ostium; SS: sphenoid sinus; ST: superior turbinate.