25 Spinal Emergencies

I. Key Points

– Prompt and accurate diagnosis of spinal emergencies is critical because return of function is highly dependent on early intervention.

– Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often the imaging modality of choice in diagnosing spinal hematomas, acute herniated nucleus pulposus, and spinal epidural abscesses.

– Trauma and tumors may also present as “spinal emergencies” and are discussed elsewhere.

II. Spinal Hematomas

– Background

• As in the cranium, these include subdural, epidural, and subarachnoid hematomas.

• In up to one-third of cases, no etiologic factor can be identified.

• Anticoagulant therapy and vascular malformations represent the second and third most common causes.

• Spinal hematomas are typically localized dorsally to the spinal cord at the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar regions.1,2

• Subarachnoid hematomas can extend along the entire length of the subarachnoid space.

• Intramedullary hemorrhages, caused by cavernomas or arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), typically produce devastating neurologic symptoms but are often not managed with emergent surgical decompression.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• Epidural and subdural spinal hematomas present with intense, knife-like pain at the location of the hemorrhage (“coup de poignard”).

• This may be followed by a pain-free interval of minutes to days.

• Subarachnoid hematoma can be associated with meningitis-like symptoms, disturbances of consciousness, and epileptic seizures (often misdiagnosed as cerebral hemorrhage based on these symptoms).

• Symptoms depend on the location and extent of hemorrhage and may include motor weakness, sensory and reflex deficits, and acute bowel/bladder dysfunction.1

– Workup

• Hematology (including platelets), electrolytes, and partial thromboplastin time (PTT)/prothrombin time (PT)/International Normalized Ratio (INR)

• Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) panel and specific hematology factors may need to be assessed.

• Appropriate neuroimaging

– Neuroimaging

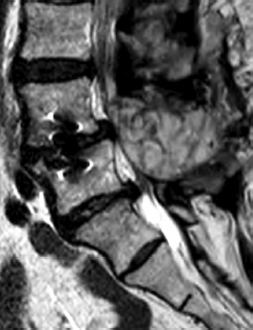

• The imaging modality of choice is MRI with or without gadolinium (Fig. 25.1).

• The appearance of hematomas in MRI is highly dependent on the age of the clot.

• Hyperacute bleeding (<24 hours): T1 isointense, T2 slightly hyperintense

• Acute bleeding (1 to 3 days): T1 slightly hyperintense, T2 hypointense

• Subacute bleeding (>3 days): T1 hyperintense, T2 hypointense (T2 may be hyperintense for late subacute)

– Treatment

• The treatment of choice is correction of coagulopathy, if present, and emergent surgical decompression.1

• Benefit of surgical intervention is debatable if only symptom is pain.

• Surgery typically involves laminectomy without the need for fusion.

• For cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junction multilevel laminectomies, consider instrumentation and fusion.

– Surgical pearls

• Subfascial drains may diminish the incidence of symptomatic epidural blood collections following multilevel laminectomy procedures.

Fig. 25.1 T2-weighted MRI of the lumbar spine showing post-operative mixed signal fluid collection (consistent with epidural hematoma) in the epidural space compressing the dural sac.

III. Cauda Equina and Conus Syndromes

– Background

• Cauda equina syndrome (CES) refers to the clinical condition that results from compressive, ischemic, and/or inflammatory neuropathy of multiple lumbar and sacral nerve roots in the lumbar spinal canal.3,4

• Conus syndrome has features similar to those of CES but involves compression at the level of the conus medullaris (T12-L1 typically).

• The most common cause is disc herniation in the lumbar region.

• It may also be caused by traumatic injury, lumbar spinal stenosis, primary or metastatic tumors, epidural abscess, ankylosing spondylitis, spinal subdural or epidural hematoma, spinal manipulation, and vascular malformation.3,4

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• Urinary retention is the most consistent finding, occurring in 90% of patients presenting with CES.

• Anal sphincter tone diminished in 80% of patients.

• Saddle anesthesia is the most common sensory deficit (75% of patients).

• Once total perineal anesthesia develops, patient will likely have permanent bladder dysfunction.

• Low back pain and radicular symptoms

• Conus lesions have the same features except that motor and sensory loss is typically asymmetric.

– Workup

• Basic laboratory studies and appropriate neuroimaging

• If imaging demonstrates pathology other than herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP), further workup is indicated (e.g., tumor or infection workup).

– Neuroimaging

• MRI is the best initial study if CES or conus syndrome is suspected.

• MRI assesses soft tissue compression as well as signal changes within the spinal cord.

– Treatment

• Prompt surgical decompression (<24 hours)

• Surgical strategy is usually focused on the underlying causes.

• Typically involves laminectomy and discectomy (for HNP)

• More extensive surgery (e.g., vertebrectomy, tumor removal) may be necessary for other pathologies.

• Return of function is dependent on the extent and duration of preoperative deficits.

– Surgical pearls

• Complete hemilaminotomy or laminectomy may be required for removal of large central disc fragment causing conus or cauda equina syndrome.

IV. Spinal Epidural Abscess

– Background

• Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) is responsible for 0.2 to 2 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations.

• Thoracic level is the most common site (50%), followed by lumbar (35%).

• Often associated with vertebral osteomyelitis/discitis

• Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, trauma, intravenous drug abuse, alcoholism, and epidural anesthesia or analgesia.

• Skin abscesses and furuncles are the most common sources of infection.

• Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative agent.

– Signs, symptoms, and physical exam

• Diagnosis is often achieved in delayed fashion due to vagueness of presenting signs and symptoms.

• The most common presenting symptoms include excruciating pain localized over the spine, radicular pain, weakness, and sensory deficits.

• Average time from back pain to root symptoms is 3 days, and 4.5 days from root pain to weakness.

• Leukocytosis and fever may be absent.

– Workup

• Hematology (complete blood count [CBC] with differential), electrolytes (comprehensive metabolic panel [CMP]), acute phase reactants (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP]), blood cultures. Cardiac echo to rule out endocarditis may be indicated.

– Neuroimaging

• MRI with gadolinium is the modality of choice in diagnosing SEA.

• Typical finding: T1 shows hypo- or isointense epidural mass; vertebral osteomyelitis shows up as reduced signal in bone. T2 shows high-intensity epidural mass that often enhances with gadolinium but may show minimal enhancement in the acute stage when composed primarily of pus with little granulation tissue.5

• Plain radiographs often helpful for suspected discitis and will show chronic, erosive changes in the end plates.

– Treatment

• For SEAs that show clear involvement of the spinal canal and cause dural compression, surgical decompression and intravenous antibiotic therapy are the treatments of choice.

• SEA is often seen in association with discitis/osteomyelitis. In these cases, typically only a thin film of epidural enhancement is seen. Surgical intervention not necessarily indicated in these situations.

• Patients with severe neurologic deficit may show minimal improvement even with surgical intervention.

• SEA is fatal in up to one-third of elderly patients, and mortality is usually due to the original focus of infection or as a complication of neurologic compromise.

– Surgical pearls

• Most spinal instrumentation is safe, effective, and at times necessary in the treatment of epidural abscess or discitis/osteomyelitis of the spine.

Common Clinical Questions

1. Cauda equina syndrome describes the clinical condition that results from what neuropathy involving multiple lumbar and sacral nerve roots?

A. Compressive

B. Ischemic

C. Inflammatory

D. All of the above

2. Conus lesions have the same features as cauda equina except:

A. Urinary retention

B. Anal sphincter tone diminished in 80% of patients

C. Saddle anesthesia

D. Motor and sensory loss typically asymmetric

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree