47 Successful Management of Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery Complications

Ameet Singh, Vijay K. Anand, and Theodore H. Schwartz

Introduction

Introduction

Endoscopic skull base surgery offers a new paradigm for the management of anterior midline skull base lesions. Its advantages over traditional open transcranial or transfacial approaches include superior visualization of lesions and surrounding neurovasculature, decreased retraction and manipulation of brain and cranial nerves, and potential improvements in surgical outcomes. Complications are an inherent part of any surgical management strategy, and endoscopic skull base procedures are no different. Preventing, minimizing, and successfully managing complications with minimal morbidity and mortality remain the goals in endoscopic skull base surgery. The management of many potential complications (e.g., endocrinologic, neurologic) in endoscopic skull base surgery is similar to transcranial surgery. Management of other complications (e.g., vascular, cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] leaks, sinonasal) differs in some respects from transcranial surgery.

Complications

Complications

Endocrinologic

Diabetes insipidus (DI) is one of the more frequently encountered complications in transsphenoidal pituitary and cranio-pharyngioma surgery. Disturbance of the posterior pituitary, pituitary stalk, and neurons from the hypothalamus may lead to temporary or permanent imbalance of antidiuretic hormone–regulated water homeostasis. The overall incidence of transient and permanent postoperative DI in transsphenoidal pituitary surgery has been reported to range from 4 to 20% (transient) and 0 to 5% (permanent)1 but may be as high as 68% for transsphenoidal craniopharyngioma.2 In our series, transient DI was experienced in 10% of endoscopic pituitary and anterior skull base approaches for a variety of tumor pathologies, with permanent DI in less than 2% of cases. Craniopharyngiomas had the highest rate (40%) of postoperative DI (unpublished data).

The recent literature has shown that patients with micro-adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, Rathke’s cleft cysts, and intraoperative CSF leak have an increased incidence of postoperative DI. In addition, transitioning from a microscopic to endoscopic pituitary surgery can be accomplished with a low incidence of DI.3 Theoretically, improved visualization, magnification, angled endoscopes, and enhanced surgical instrumentation should enable surgeons to better preserve the posterior pituitary, pituitary stalk, hypothalamic nuclei, and supporting vasculature. Preservation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and supporting vasculature through meticulous surgical dissection is paramount to preventing postoperative transient or permanent DI.

Vascular

Vascular complications include hemorrhage and stroke. Bleeding can entail nasal mucosal bleeding from a traumatic opening, troublesome slow oozing at the tumor bed, brisk venous bleeding from the cavernous sinus, pulsatile arterial bleeding from a small intracranial perforator, arterial bleeding within the nose from branches of the sphenopalatine artery, or more devastating arterial injuries to the internal carotid artery. Each of these vascular injuries can be managed in a variety of ways. Meticulous intraoperative hemostasis is essential for the approach to and resection and reconstruction of the skull base. Nasal mucosal bleeding can be managed with injection of epinephrine, direct cautery, or application of hemostatic agents such as FloSeal (Baxter, Deerfield, IL). Bleeding from the sphenopalatine artery usually requires direct cautery or ligation. Control of venous ooze within the brain can be managed with warm saline irrigation, thrombin-soaked Gelfoam, gentle pressure, FloSeal, and bipolar electrocautery. Arterial bleeding from small intracranial vessels is quite tricky because the parent artery must often be preserved to prevent stroke. Direct cautery to “weld” the opening closed is ideal. Pressure with FloSeal may work in some circumstances, and sacrifice of the parent artery is a last resort (Fig. 47.1). Internal carotid artery (ICA) injury is best avoided by thoroughly studying the neurovascular anatomy on preoperative imaging, and utilizing image guidance and Doppler intraoperatively. These techniques are imperative to confirm anatomical landmarks and avoid a vascular injury.

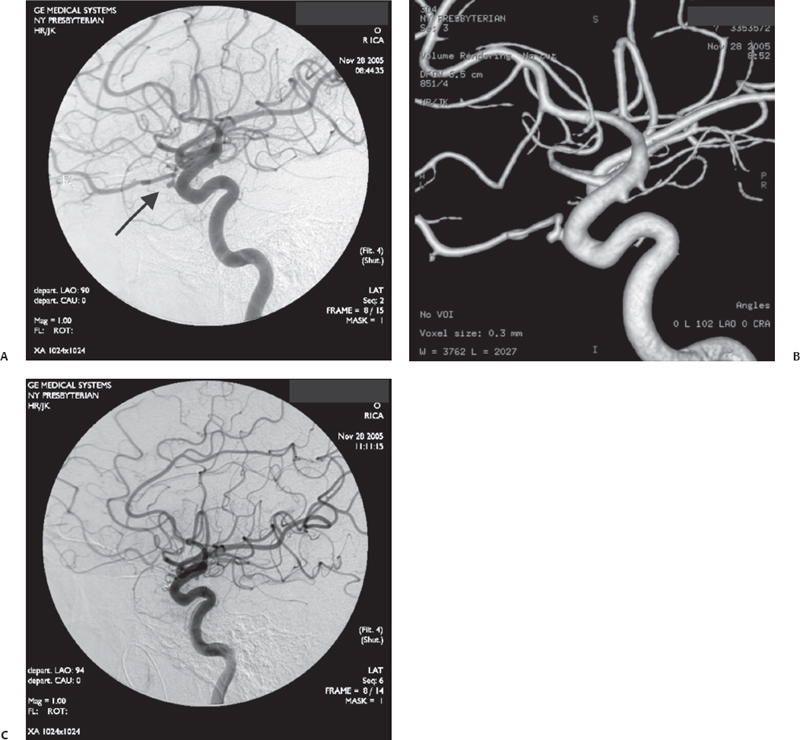

Fig. 47.1 Pseudoaneurysm at the origin of the ophthalmic artery demonstrated on angiogram (A) and three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction (B). (C) Definitive treatment consists of occlusion of the ophthalmic artery at its origin. There were extensive collaterals feeding the artery through the external circulation and ethmoidal arteries, so vision was preserved.

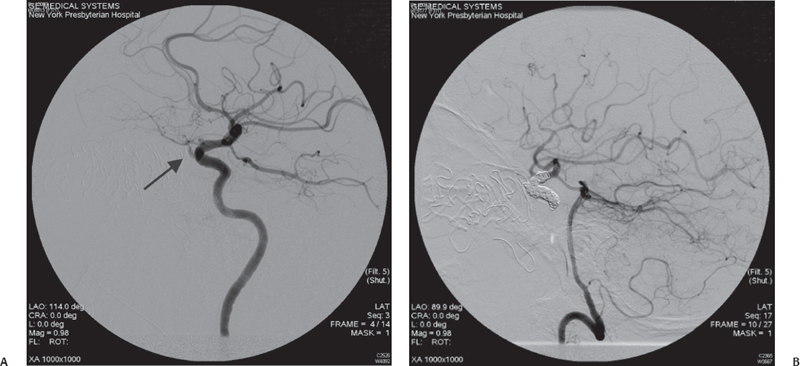

In the event of a major vascular injury (<1% in our series of 250 patients), direct pressure with packing and placement of a Foley balloon will usually be suitable for temporary control. Once the acute bleeding is managed, immediate transfer to interventional neuroradiology for angiography is optimal. A perforation in the carotid can be managed by stenting or occlusion (Fig. 47.2). A balloon occlusion test is advisable prior to sacrificing the artery, to assess the presence of collateral flow and the patient’s ability to tolerate occlusion. Stenting may be performed but requires anticoagulation and is currently not Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for treating these injuries. If a stent is placed, repeat endonasal surgery can be performed to further cover the defect in the artery with tissue sealant.

Fig. 47.2 (A) Internal carotid artery injury (arrow) within the sphenoid sinus is demonstrated with the extravasation of contrast material from the internal carotid artery (ICA) into the sphenoid sinus. (B) Definitive repair in this case included occlusion of the ICA. Notice that the anterior circulation fills through the posterior communicating artery.