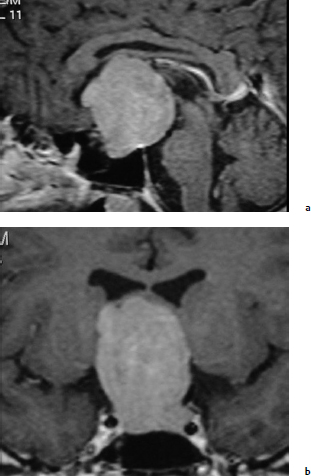

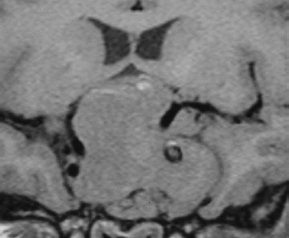

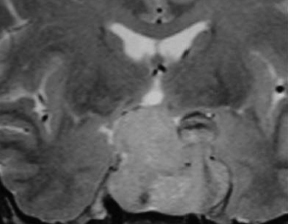

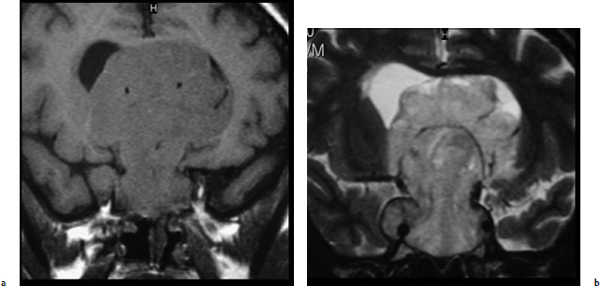

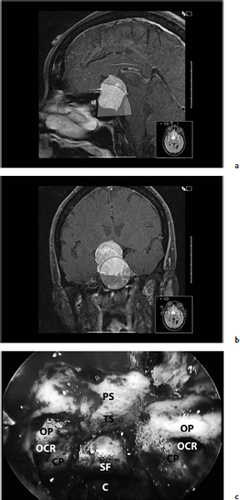

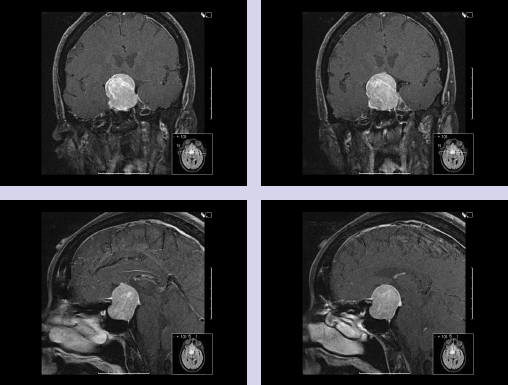

Chapter 7 Case A 45-year-old man presented with bitemporal hemianopsia and a nonsecreting pituitary tumor. Participants Is the Endoscope Useful for Pituitary Tumor Surgery?: Atul Goel Endoscopic Removal of a Pituitary Macroadenoma: John A. Jane, Jr., Stephen J. Monteith, and Michael S. McKisic The Endonasal Combined Microscopic Endoscopic with Free Head Navigation Technique to Remove Pituitary Adenomas: Ossama Al-Mefty, Mohamad Abolfotoh, and Cristian Gragnaniello Moderator: Surgical Removal of a Pituitary Macroadenoma: Endoscopic vs. Microscopic: Mario Ammirati The introduction of the microscope drastically changed the entire visual aspect of pituitary tumor surgery. Good depth lighting and the ability to work with comfort and ease have made it possible for the surgeon to control the conduct of the entire operation. Thus, pituitary tumor surgery has become one of the most results-oriented neurosurgical procedures. After successful surgery, there can be a dramatic and immediate improvement in vision, a reversal of acromegaly and cushingoid features, and other similar results. Giant pituitary tumors are among the most complex neurosurgical challenges. Despite their histologically benign nature, some of these tumors grow to a massive size. Because of the invasiveness and size of such tumors, surgical resection is difficult and, in some cases, dangerous.1 But because the results of radiation therapy are inconsistent, surgery forms the mainstay of treatment. The diagnosis of a pituitary tumor usually can be made on the basis of clinical features and their classic anatomic extensions seen on imaging.2 Surgical biopsy for histological confirmation has no relevance. Small or partial resections can be dangerous, as bleeding from the residual tumor is frequent, an event defined earlier as “post operative pituitary apoplexy.”1 Successful radical resection of the tumor can rapidly dispel symptoms and lead to an excellent long-term clinical outcome. After such resection, the recurrence rate of these tumors is low. Giant pituitary tumors have a maximum transverse dimension of at least 3 cm and can be divided into four grades: Grade I tumors are located within the confines of the sella, remain underneath the superiorly elevated diaphragma sellae, and do not invade the cavernous sinus (Fig. 7.1). The diaphragma sellae is stretched superiorly, sometimes even beyond the corpus callosum, and it covers the entire superior dome of the pituitary tumor. Although the suprasellar extension of the tumor is intracranial, it is referred to as subdiaphragmatic. Grade II pituitary tumors invade the cavernous sinus (Fig. 7.2). There is no exact anatomic or histological reason why some tumors extend into the cavernous sinus and some do not. Although several studies discuss the issue, the nature of the membranes that demarcate the cavernous sinus from the pituitary gland remains controversial.5 Transgression of the lateral dural wall of the cavernous sinus has not been reported. Grade III pituitary tumors elevate the roof of the cavernous sinus superiorly (Fig. 7.3). Grade IV pituitary tumors transgress the boundary of the diaphragma sellae and enter the subarachnoid spaces of the brain (Fig. 7.4). These tumors encase the arteries of the circle of Willis and are considered aggressive because of their anatomic, clinical, and surgical behavior. In use for quite some time now, endoscopes are currently being recommended for several neurosurgical operations. The superiority of the endoscope in treating tumors of the paranasal sinus and clival regions and medial extradural cavernous sinus tumors is now accepted. The campaign in favor of the use of the endoscope has been quite intense. Even the general population has come to know this tool, and some patients even demand that their pituitary surgery be done with an endoscope. Several surgeons who are accustomed to using the microscope for pituitary tumor surgeries have acknowledged the value of the endoscope. Fig. 7.1a,b (a) Contrast-enhanced sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a grade I pituitary tumor. The diaphragma sellae is elevated by the giant tumor. (b) Coronal image of the tumor. Fig. 7.3 Coronal MRI of a grade III pituitary tumor. The roof of the cavernous sinus is elevated by the tumor, which is also under the superiorly elevated diaphragma sellae. The tumor in the presented case is a large, but not giant, grade I pituitary tumor. The sella is large and ballooned, but the tumor does not invade the cavernous sinus. The tumor appears to be of a standard consistency and vascularity. My experience with pituitary tumor operations exceeds 1,700 cases over a 14-year period, and I prefer to do all pituitary tumor surgeries using the sublabial transseptal and transsphenoidal operative route with a microscope. I find the use of an endoscope, even as an assistant tool to the microscope, redundant and unnecessary. Although the nostril is currently the route preferred by some surgeons, I do not like to do the operation through this route, as it limits the exposure and restricts the ability to open the speculum widely. Furthermore, damage to the hair follicles and the skin of the nostril can be quite painful for the patient. The sublabial approach is a cleaner avenue, is midline, and provides sufficient exposure to open the speculum widely. I do not use coagulation equipment on the operating table, and have found that coagulation can be entirely avoided in pituitary tumor surgery. Although this technique does create some bleeding in the operative field, it can easily be handled with the microscope. On the other hand, if one uses an endoscope, extensive mucosal coagulation may be necessary to provide a blood-free field, which prevents fogging of the endoscope lens. Fig. 7.4a,b (a) T1-weighted MRI of a grade IV tumor. Both anterior cerebral arteries are encased by the tumor. (b) T2-weighted image showing encasement of the anterior cerebral artery complex. Tumor resection is begun from the sella in the midline, and is followed by resection in the lateral aspect of the sella. It then continues superiorly. As resection continues, the tumor progressively falls and comes down into the operative field. The Valsalva maneuver is used during surgery to facilitate descent of the tumor mass, but to get the tumor into the field inferiorly requires experience and confidence. Frequently, the diaphragma sellae has to be retracted superiorly to expose the tumor within its folds. In my experience with pituitary tumors of grades I to III, the tumor under the diaphragma sellae can invariably be resected. Although some tumors are relatively firm and even fibrous and “elastic,” they can always be progressively debulked, brought inferiorly into the operative field, and resected. In our early experience, to resect the suprasellar component of the tumor, we preferred to remove the bone of the tuberculum sellae and planum sphenoidale. However, we have realized that removing this bone is necessary for only a minority of patients and can frequently be avoided even in patients with much larger tumors than that in the presented case. The use of the endoscope to view the suprasellar component is unnecessary, as the diaphragma sellae should be viewed anteriorly in the surgical field at the end of tumor resection. The use of curettes to resect the tumor in the lateral parts of the sella is generally satisfactory if the surgeon has sufficient experience in pituitary tumor surgery. The use of the endoscope for lateral visualization can be helpful but is not mandatory. Some large tumors can be extensively vascular. In such cases, tumor resection has to be done during profuse bleeding. In such cases, it is much safer and more comfortable to use a microscope rather than an endoscope. On some occasions, there can be profuse bleeding from the cavernous sinus. With experience it may be possible to control such bleeding with an endoscope, but surgery under the microscope can be much more controlled in such a situation. Reconstruction of the region after surgery is rather straightforward when the conventional microneurosurgical approach is used, and the cerebrospinal fistula rate in most of the reported series is less than 2%. Resecting the tumor within the confines of the cavernous sinus is a relatively complex technique. The anterior loop and the horizontal portion of the carotid artery can be exposed with a microscope and appropriate angulation of the speculum; however, working around the carotid artery depends mainly on the consistency of the tumor. In some cases, tumors that extend into the cavernous sinus are softer and more necrotic than those with no cavernous sinus extension. In these cases, the tumor can be resected safely and radically. However, whether to resect the section of tumor in the cavernous sinus in patients with nonfunctional pituitary tumors is controversial. Even in patients with a functioning pituitary tumor, whether to resect the cavernous sinus portion is controversial. In desperate situations in patients with functioning pituitary tumors, a lateral, basal, subtemporal extradural route can be used to resect this portion of the tumor. The advantages of using the endoscope to radically resect the portion of tumor within the cavernous sinus are yet to be evaluated and confirmed. Apart from providing good images of the lateral aspect of the sella and optic nerves as well as the carotid artery bulge in the sphenoid sinus, there are no significant advantages in using an endoscope for pituitary tumor surgery. The need for extensive mucosal coagulation and the limitations in having to control bleeding can severely limit the ease of tumor resection with the endoscope. The ancient Egyptians were the first to recognize the possibility of accessing the brain endonasally without disfigurement. Computed tomography scans of mummies and archaeological findings confirm that the Egyptians used specialized instruments to perform the earliest transsphenoidal approaches, albeit postmortem.6 It would be several thousand years before Schloffer, Von Eiselberg, and Kocher would carry out, in 1907, the earliest transsphenoidal surgeries to access a pathological lesion.7 The sublabial transseptal approach was used by Cushing8 in 1909 and was less traumatic than the endonasal and sublabial approaches introduced in 1910 by Hirsch and Halstead, respectively.7 Cushing abandoned the approach, however, in part because of inadequate illumination, but in the late 1960s, Hardy overcame this obstacle by making use of the operating microscope. Since then, approaches have been modified with improved visualization for the surgeon and decreased postoperative discomfort for the patient. The approaches done with the microscope essentially differ according to where the mucosal incision is made (sublabial, hemitransfixion, Killian, or direct sphenoidotomy) and the width of the sellar exposure each provides. Whereas the sublabial approach provides the widest exposure, it also requires the most soft tissue and mucoperichondrial dissection. By contrast, the direct endonasal sphenoidotomy requires no anterior septal dissection but has the narrowest exposure. The endonasal approaches decrease both the postoperative discomfort for the patient and the chances of anterior septal complications. However, the downsides of more direct approaches include diminished working room, a more limited sellar exposure, and an approach from an angled trajectory.7 The role of the endoscope has evolved over time. Initial reports describe the use of the endoscope as an adjunct to the standard approach with the microscope.9,10 For example, the endoscope could be used for the anterior sphenoidotomy before introducing the microscope, or it could be simply introduced at the end of resection to inspect for residual tumor. The pure endoscopic transsphenoidal approach was introduced by Jho and Carrau11 in the late 1990s, with modifications by Kassam and colleagues12,13 that allowed the scope of the approach to expand to surgery for complex skull-base tumors. Other pioneers include Cappabianca and de Divitiis14,15 in Italy, as well as Frank, Pasquini, Locatelli, and others who have made significant contributions to the development of endoscopic techniques and transsphenoidal surgery.16–18 The primary advantages of the endoscopic removal of adenomas lie in the panoramic field of view and the ability to attain an extreme close-up point of view. During the approach, the panoramic view allows superior visualization of the sphenoid anatomy. Unlike the approach with the microscope, in which a localization X-ray is necessary after speculum placement, image guidance is rarely needed during a standard endoscopic approach, which decreases the dose of radiation to both the patient and operator. Anatomic landmarks are clearly identifiable, even by the novice endoscopist, which increases the surgeon’s confidence and decreases the learning curve.19 In the case of a repeated operation, distorted anatomy can be more clearly identified, and the existence of an operative corridor facilitates surgery with less risk of complications.7,15 In addition, because there is no submucosal dissection, nasal packs are not routinely used, which improves overall patient satisfaction with the procedure. Most significantly, the panoramic view allows a greater portion, if not all, of an adenoma to be removed under direct visualization. Tumor extensions toward the cavernous sinus walls and the suprasellar portions, which are often removed blindly by feel during an approach with the microscope, are instead removed with certainty. The magnification allows excellent visualization of the interface between the tumor and pituitary gland, potentially facilitating adenomectomy with minimal disruption of the surrounding tissues.15 With the wide-angle lens view of the zero-degree endoscope and the use of angled endoscopes, the endoscopic surgeon can see around corners, which is not possible with the microscope.16 This ability can be particularly helpful in patients with a macroadenoma that extends into the cavernous sinus or suprasellar space.17 For tumors that invade the cavernous sinus, the endoscope affords a wider view when compared with the microscope and unrivaled maneuverability in the lateral compartment of the cavernous sinus.17 Moreover, only the endoscope allows the surgeon to use the diving technique described by Locatelli and colleagues.18 Intrasellar hydroscopy allows for more complete assessment of the surgical bed, during and after resection, with improved hemostasis. Blind curettage is therefore minimized and a larger extent of the tumor can be removed under direct visualization. Despite its advantages, there are several disadvantages of the endoscopic approach, many of which can be overcome with training and experience. Neurosurgeons are comfortable using the operating microscope and the three-dimensional view it provides. When using the endoscope, a new skill set with a different type of hand–eye coordination must be learned and practiced. Some surgeons find the two-dimensional view on a monitor challenging, particularly with regard to depth perception.19,20 This problem can be partly overcome with the help of a skilled endoscopist as the assistant. Such an assistant can help the surgeon with opportune in-and-out movements of the camera to create an artificial perception of depth. This notion of the endoscope as part of a “clock gear” mechanism was aptly described by Cavallo and associates.21 Each part of the system depends on the others. If one part fails then the whole system fails. In addition, proprioception allows the surgeon to perceive the location of an instrument in one hand as it relates to the instrument in the other. Because of the current constraints with rigid endoscopes, there is a slight “barrel distortion” effect at the edges of the field of view. When the endoscope cannot be repositioned, an angled scope can overcome these distortive effects so that the surgeon can examine the edges and beyond the resection bed. The endoscope does occupy space within the operative field and can obstruct the free movement of surgical instruments. Whereas the operative field during an adenomectomy done with the microscope is occupied by two instruments (suction and the dissector), the endoscopic technique requires the surgical field to be occupied by an additional instrument—the endoscope itself. Therefore, there is less room to maneuver instruments, and the sphenoidotomy must be larger to allow a similar range for instrument movement. Furthermore, the approach with the microscope is facilitated by the use of a nasal speculum, which is not typically used during an endoscopic approach because it occupies a significant amount of space and creates a rigid avenue that is not conducive to the approach. Without a speculum, the nasal mucosa is placed at risk of injury when instruments are introduced and the surgeon has greater difficulty freely introducing instruments and performing precise dissection during the removal of microadenomas. The case presented is that of a 45-year-old man with a nonfunctioning pituitary macroadenoma causing bitemporal hemianopsia. The representative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a large macroadenoma with a suprasellar extension (Fig. 7.5). Coronal images show likely cavernous sinus involvement bilaterally. Therefore, a complete resection is unlikely regardless of whether an endoscope or microscope is used. The primary goal of surgery is to decompress the optic chiasm. Secondary goals are to remove enough of the tumor to prevent recurrence and to preserve pituitary function. Because the patient is relatively young, these goals require as thorough a removal of tumor as possible. Fig. 7.5a–c (a) Sagittal view of the lesion with the endoscopic view superimposed in gray. (b) Coronal view of the lesion with the endoscopic view superimposed in gray. (c) Endoscopic photograph from within the sphenoid sinus of a different patient. C, clivus; CP, carotid protuberance; OCR, opticocarotid recess; OP, optic protuberance; PS, planum sphenoidale; SF, sellar floor;TS, tuberculum sellae.

Surgical Removal of a Pituitary Macroadenoma: Endoscopic vs. Microscopic

Is the Endoscope Useful for Pituitary Tumor Surgery?

Anatomic Grading of Giant Pituitary Tumors3,4

The Use of the Endoscope in Pituitary Tumor Surgery

Personal Technique for the Presented Case

Endoscopic Removal of Pituitary Macroadenoma

Historical Perspectives on the Endoscopic Approach

Evolution of the Endoscopic Approach

Advantages of the Endoscopic Approach

Disadvantages of the Endoscopic Approach and Strategies for Their Management

Case Presentation and Relevance to the Described Technique

Surgical Technique

Surgical Removal of a Pituitary Macroadenoma: Endoscopic vs. Microscopic

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree