Chapter 71 Surgical Treatment of Moyamoya Disease in Adults

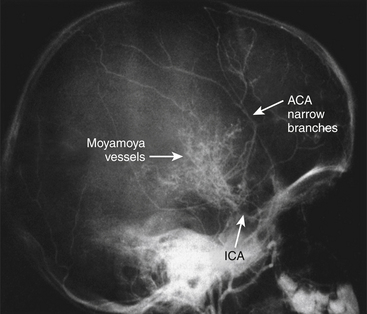

Moyamoya disease is a chronic, cerebrovascular occlusive disease, in which the terminal portions of the intracranial internal carotid arteries and the initial segments of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries progressively become narrowed or occluded. Due to this phenomenon, reduced blood flow to the brain is produced, and tiny collateral vessels at the base of the brain enlarge to become collateral pathways. These vessels are called “moyamoya vessels” because the angiographic appearance of these vessels resemble the “cloud” or “puff” of cigarette smoke, which is described as “moya-moya” in the Japanese language; also, “moya-moya” is the Japanese word to describe a hazy appearance or an unclear idea about something.1

In the 1950s, leading Japanese neurosurgeons began to notice a new clinical entity that came to be called moyamoya disease. Since its etiology was unknown, it was named in various ways. Takeuchi and Shimizu described it as a hypoplasia of bilateral internal carotid arteries.2 Later, Suzuki and Takaku described in detail the angiographic appearance and development of this disease,1 and gave it the name moyamoya disease. Kudo named it officially as the spontaneous occlusion of the circle of Willis3 (Fig. 71-1).

Clinical Findings and Preoperative Assessment

Symptoms and signs of moyamoya disease include brain ischemia and hemorrhage. Initial symptoms in moyamoya disease, both juvenile (under age 15 years) and adult cases considered together, are most frequently motor disturbances. In the experience of Suzuki.4 these were found in 36% of patients, followed by intracranial hemorrhage in 25%, headache in 20%, and convulsions in 6%. This is similar to the experience reported by Yamaguchi et al.,5 who reported motor disturbances in 62.7% of males and 53.8% of females, disturbances of consciousness in 28.1% of males and 34.6% of females, signs of meningeal irritation in 10.3% of males and 20.5% of females, and speech disturbances 16.7% of males and 14% of females.

Among the juvenile cases, motor disturbances, including monoparesis, paraparesis, and hemiparesis are found in 60%, and in these juvenile cases, some 20% show motor disturbances indicative of transient brain ischemia.4

If we also included other symptoms thought to be due to brain ischemia, such as sensory disturbances and mental and psychic disorders, then 85% of these juvenile cases show symptoms of brain ischemia. Intracranial hemorrhage was seen in only 4% of juvenile cases.4

In other Japanese reported experiences,4,6,7 the onset of adult cases was accompanied by intracranial hemorrhage in 43% of patients, and symptoms due to brain ischemia,8,9 including motor, mental, and psychic disturbances, were seen in 20% of these adult cases.

Moyamoya disease is basically diagnosed both by clinical symptoms and angiographic findings.

Neuroimaging

The widespread availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) as useful and safe imaging methods has led to the increasing use of these methods for primary imaging in patients with symptoms suggestive of moyamoya.10–12 An acute infarct is more likely to be detected with the use of diffusion-weighted imaging, whereas a chronic infarct is more likely to be seen with T1- and T2-weighted imaging. Diminished cortical blood flow due to moyamoya can be inferred from fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences showing linear high signals that follow a sulcal pattern, which is called the “ivy sign.”13

The finding most suggestive of moyamoya on MRI is reduced flow voids in the internal, middle, and anterior cerebral arteries coupled with prominent flow voids through the basal ganglia and thalamus from moyamoya-associated collateral vessels. These findings are virtually diagnostic of moyamoya,14 and also called “the sign of termite nest.”15

When we search for the classical findings of moyamoya disease, both studies, catheter angiography and MRA, show the terminal portions of the intracranial internal carotid arteries and the initial segments of the middle and anterior cerebral arteries progressively become narrowed or occluded. According to the report by Suzuki et al.1 that named this disease, tiny collateral vessels at the base of the brain enlarge to become collateral pathways. These vessels are called “moyamoya vessels” because the angiographic appearance of these vessels resemble the “cloud” or “puff” of cigarette smoke, which is described as “moya-moya” in the Japanese language.

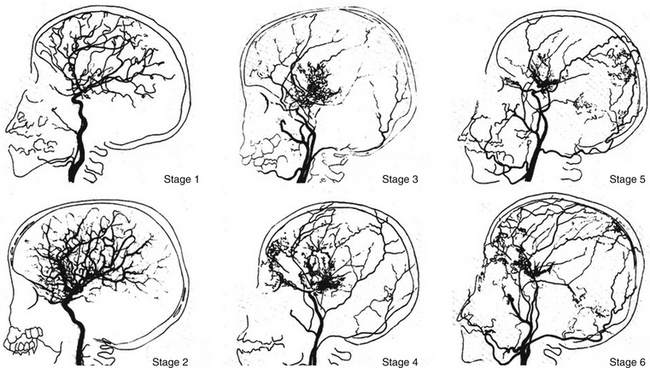

Suzuki and Takaku1 classified the development of moyamoya disease into six stages. According to this classification, many patients fall into stage 3. Fukuyama and Umezu16 then further divided stage 3 into three.

Stage 1: Narrowing of carotid fork.

Stage 2: Initiation of the “moyamoya vessels”; dilatation of the intracerebral main arteries.

Stage 3: Intensification of the “moyamoya vessels”; nonfilling of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries.

Stage 4: Minimization of the “moyamoya vessels”; disappearance of the posterior cerebral artery.

Stage 5: Reduction of the “moyamoya vessels”; the main arteries arising from the internal carotid artery disappear.

Stage 6: Disappearance of the “moyamoya vessels”; the original moyamoya vessels at the base of the brain are completely missing and only the collateral circulation from the external carotid artery is seen (Fig. 71-2).

FIGURE 71-2 Angiographic staging of moyamoya disease.

(From Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular “moyamoya” disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:288-299.)

Inconveniences of this classification are as follows: Many cases belong to stages 3 to 5, especially to stage 3. There are few cases in stages 1 and 6. Stages of moyamoya disease are not strongly related to clinical symptoms. In stages 1 and 6, there are no moyamoya vessels on cerebral angiography, which is not moyamoya disease by definition. There is some doubt that vascular dilatation in stage 2 really exists.

CBF, positron-emission CT or single-photon CT, or xenon inhalation CT are commonly used to obtain greater detail. Recently, perfusion x-ray CT and MRI with contrast materials have been used for this purpose.17,18

Emergency Treatment

In the acute stage, the treatment is the same as for brain infarction or spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage due to other etiologies.19 In the event of ventricular hemorrhage, an external ventricular drainage operation is performed if the patient presents in acute evolution with signs of intracranial hypertension.20,21

In the case of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), initial medical treatment is indicated if the hemorrhage totals less than 25 cc in volume. If the hemorrhagic volume totals more than 25 cc, is associated with a lobar topography, and demonstrates mass effect over the midline structures, then surgical evacuation is indicated.20 In patients with ICH, infusion of osmotic agents is frequently used to control the intracerebral pressure and edema, as well as administration of anticonvulsants to control seizures, is also required.21

Bypass surgery in the acute stage of the disease is not indicated.19

Treatment in the Chronic Stage

Patients with Cerebral Ischemia

There is no consensus on medical treatment with aspirin, other antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, vasodilators, or corticosteroids to prevent future ischemic attacks in patients with chronic disease.22

Surgical Anastomosis

In order to eliminate ischemic symptoms or to prevent recurrent ischemic stroke, bypass surgery is accepted as the treatment of choice. Site of the bypass is also determined occasionally by the results of the examination of cerebral blood flow (Xe133-CT scan, SPECT, PET scan).22 The rationale to initiate some form of revascularization follows:

Clinical picture: As already described, there are mainly different forms of ischemic stroke in children (juvenile cases), and hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke in young adults.

Laboratory studies: The following studies may be indicated in patients with moyamoya disease: In a patient with stroke of unclear etiology, a hypercoagulability profile may be helpful. Significant abnormality in any of the following is a risk factor for ischemic stroke: protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, homocysteine, and factor V Leiden. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) can be obtained as part of the initial workup of a possible vasculitis. However, a normal ESR does not rule out vasculitis.

Imaging studies: Cerebral angiography is the criterion standard for diagnosis. The following findings support the diagnosis:

Vascular anastomoses are classified as direct or indirect. In direct anastomosis, the superficial temporal artery (STA) in the scalp is dissected and anastomosed with the middle cerebral artery (MCA) on the brain surface under microsurgery. This surgical technique gives the patient a high cerebral blood flow (CBF) immediately after the surgery.23–26 However, in this disease the diameters of the cortical arteries are very small, and the anastomotic technique requires for its proper implementation cortical arteries of at least 1 mm in diameter.

In the indirect anastomosis, the periosteum, dura mater, or a slice of the temporal muscle is placed over the brain surface, in anticipation of the development of new spontaneous anastomoses between extra and intracranial circulation. Some time is required to establish such anastomoses that also function with utility. Thus, the brain parenchyma is provided with collateral circulation through these structures, the STA, deep temporal artery, middle meningeal artery, and anterior meningeal artery. During the surgical technique (synangiosis), these arteries must be preserved. In some cases, and to ensure close contact between the STA and galea surrounding the cerebral cortex, the extirpation of the pia mater is done in zones or “windows,” suturing the edges of the galea to the piamater.27 While using these indirect techniques, a high increase of cerebral blood flow does not develop immediately; early revascularization is frequently observed between 3 to 6 months following the intervention, especially in cases that course with cerebral ischemia.

It is common to add an indirect bypass more or less when a direct bypass is scheduled.23 In other situations, multiple burr-hole surgery is performed, in which multiple small holes are made on the skull bone, in anticipation of the development of spontaneous anastomoses.28,29 Other less frequent surgeries are omental transplantation30 and omental transposition.31

In moyamoya disease, usually both cerebral hemispheres are ischemic; thus bypass surgery is required bilaterally. First, one-sided operation for the hemisphere that is more ischemic is performed, and then bypass surgery for the opposite side is scheduled 2 or 3 months later.

The indirect revascularization techniques most widely used are the encephalo-duro-arterio-synangiosis (EDAS) and the encephalo-myo-synangiosis (EMS).32–34 There are many modes of indirect anastomoses. Such techniques reviewed by Matsushima et al.35 are summarized in Table 71-1.

Table 71-1 Procedures Using Different Tissues for Indirect Anastomoses

Patients with Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Donor vessel (the STA) should be selected with an external diameter not less than 1 mm because vessels of smaller diameter have a high percentage of occlusion, deliver a low blood flow, are not useful, and are more difficult to anastomose.23–26 To prevent mechanical vasospasm, it is useful to apply topical diluted papaverine or nimodipine.

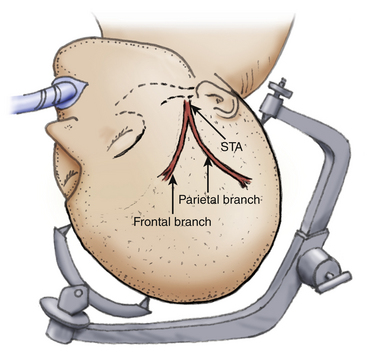

The patient is placed on the operating table with the head rotated toward the contralateral side and the temporal bone is parallel to the floor, kept in position by the head holder with three points. After the scalp is shaved, the standard Doppler ultrasound is used over the donor artery and correlated with the preoperative angiography to locate the most suitable branch of the STA. The skin is painted with its branches using a marker pen. Usually there are two branches of the STA, the frontal and parietal. Both must be marked during the proceedings (Fig. 71-3).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree