9

Temporal Bone Surgery

The temporal bone is an area of convergence between Neurosurgery and otolaryngology. Disease processes that begin in the mastoid can affect the intracranial contents, and vice versa. Treating the complications from disease extension or surgical intervention in the mastoid may require cooperation between the neurosurgeon and the otolaryngologist. An understanding of the anatomy, disease processes, and surgical procedures in the mastoid prepares the neurosurgeon for collaboration in this area.

♦ Anatomy

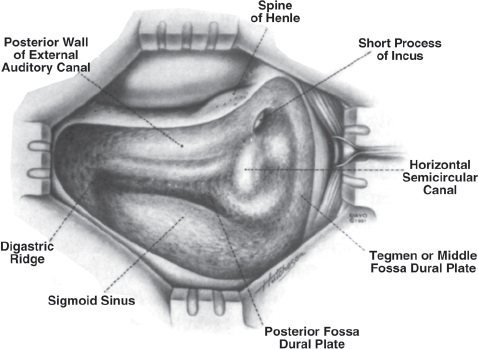

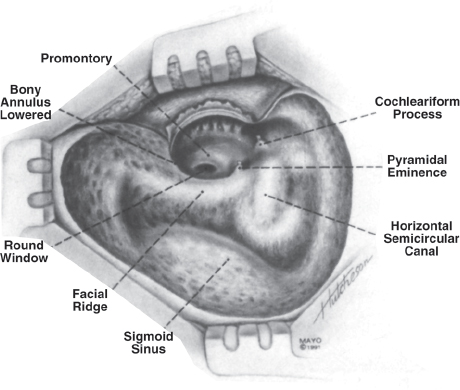

The mastoid cavity is bounded laterally by the bony cortex, superiorly by the middle cranial fossa, posteriorly by the sigmoid sinus and posterior fossa dura, and inferiorly by the cortex of the mastoid tip. The anterior limit is the posterior border of the external auditory canal, the middle ear, and facial nerve (Fig. 9.1). The medial border is more complex, and is made up of the cochlea, semicircular canals, and the petrous apex. The normal bony cortex between the mastoid cavity and the middle or posterior fossa dura is rarely more than 1 mm thick, and natural dehiscence in the bone is common.

The mastoid cavity is a complex system of interconnected air cells that communicate directly with the middle ear through the mastoid antrum. In the disease-free state, aeration of these cells is maintained by their connection with the nasopharynx through the eustachian tube, middle ear, and mastoid antrum. Understanding this system is crucial to understanding the pathology of the middle ear and mastoid cavity. In short, obstruction of this air cell system at any step can result in disease.

♦ Pathology of the Mastoid

Infectious

Otitis Media

Otitis media is an infection of the middle ear and often involves the mastoid cavity via its connection through the mastoid antrum. Otitis media is more common in patients with dysfunctional eustachian tubes. The function of the eustachian tube is to maintain an air-containing middle ear space by allowing air to pass intermittently from the nasopharynx to the middle ear with swallowing or yawning. The efficiency of the eustachian tube varies from person to person and throughout life. The reasons for this are not always clear, but hypotheses include the weakness of muscles that open the eustachian tube, upper respiratory tract infections, allergies, mucociliary disorders, and surgery or radiation treatment to the head and neck. Children are more prone to otitis media because their eustachian tube is shorter and the angle of the eustachian tube with the nasopharynx is less acute, making contamination of the middle ear by nasopharyngeal secretions more likely.

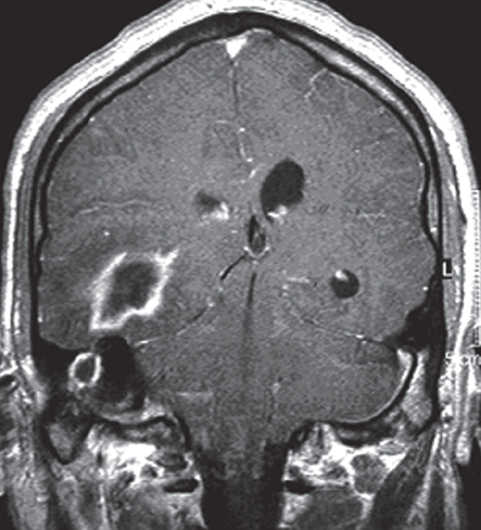

Acute otitis media is usually a self-limited infection caused by the common upper respiratory pathogens Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Moraxella catarrhalis. The time to resolution is reduced with antibiotic treatment.1 Complications of otitis media are possible, even in the age of antibiotics, and they are important because otitis media is so common. Acute coalescent mastoiditis is the most common complication of otitis media manifested by severe infection of the pneumatic spaces and the mastoid cavity, anterior displacement of the auricle, and tender postauricular swelling. Otitis media is still a common cause of meningitis in children. Facial nerve paralysis, petrous apicitis, labyrinthitis, epidural or subdural abscess, and lateral sinus thrombosis are all potential complications of otitis media2 (Fig. 9.2).

Fig. 9.1 Anatomy of the mastoid cavity. (Courtesy of the Mayo Foundation.)

Fig. 9.2 An otogenic brain abscess.

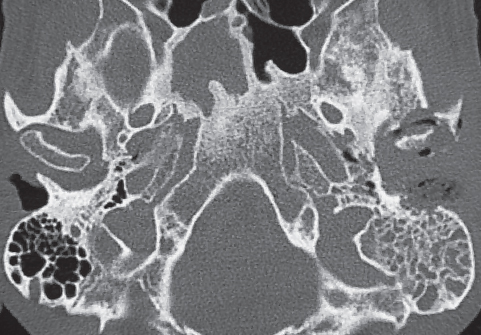

Fig. 9.3 Malignant otitis externa with bony erosion of the mastoid cortex and invasion into the temporal mandibular joint. (Courtesy of Medlocyclopaedia [http://www.medcyclopaedia.com], Amersham Health.)

Otitis Externa

Otitis externa (swimmer’s ear) is an infection of the external auditory canal that can have overlapping symptoms with otitis media. Otitis externa is an infection of the skin of the external auditory canal and causes pain, discharge, and hearing loss. The middle ear is not involved. Rarely, otitis externa can develop into malignant otitis externa, an osteomyelitis of the bony external auditory canal, mastoid cavity, and skull base. Malignant otitis externa is caused by P. aeruginosa in 98% of cases, and occurs most frequently in diabetics or other immunosuppressed patients. Cranial nerve paralysis, jugular vein thrombosis, and intracranial extension are possible complications3 (Fig. 9.3).

Benign Neoplasms

There are over 25 different benign neoplasms described in the temporal bone. We limit our discussion to the three most common: cholesteatoma, chemodectoma, and cholesterol granuloma.4

Cholesteatoma

A cholesteatoma (keratocyst) is an accumulation or mass of keratinizing squamous epithelium within the middle ear or mastoid. Primary acquired cholesteatomas develop from retraction pockets in the upper portion (pars flaccida) of the tympanic membrane. Secondary acquired cholesteatomas develop from skin migrating into the middle ear through marginal perforations of the tympanic membrane. Congenital cholesteatomas are rare, and appear to originate from embryonic rests of ectodermal tissue found medial to the tympanic membrane.

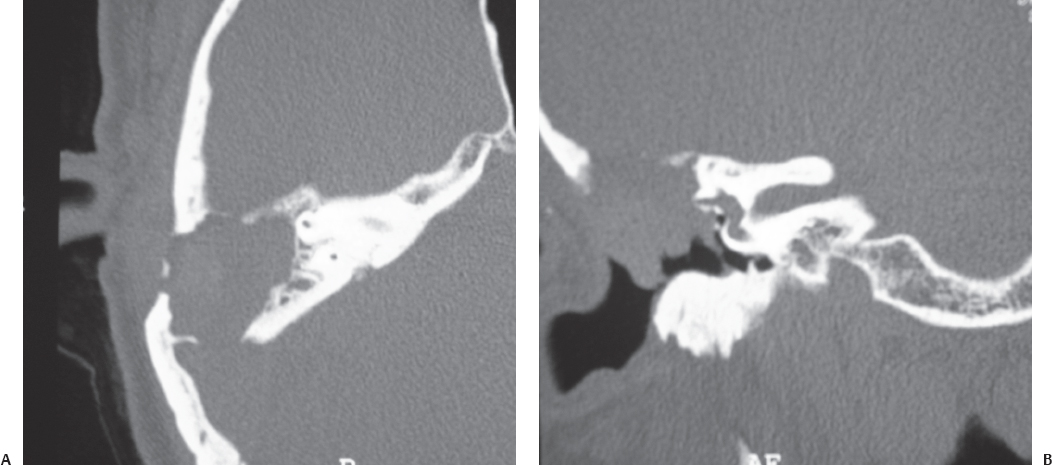

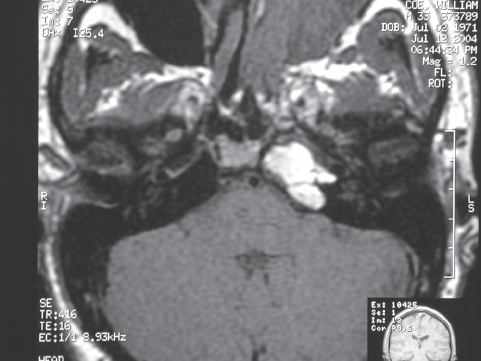

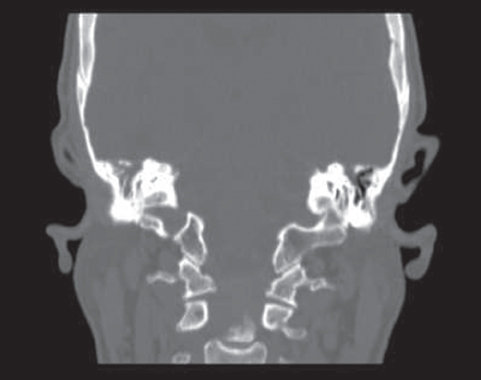

Fig. 9.4 Axial (A) and coronal (B) computed tomography (CT) images of right ear cholesteatoma with erosion through the tegmen tympani and horizontal semicircular canal.

Once inside the endodermal space of the middle ear or mastoid cavity, these ectodermal cells grow without contact inhibition. Unable to desquamate like normal epithelium, the cholesteatoma accumulates keratin and expands in size. Pressure from the growing cyst, and perhaps lytic enzymes produced by the cholesteatoma, causes the slow destruction of middle ear and mastoid structures.

The most common complication of cholesteatomas is conductive hearing loss from interference or erosion of the middle ear ossicles. Cholesteatomas may also erode into the semicircular canals, cochlea, or facial nerve causing vertigo, deafness, or facial paralysis, respectively. Invasion through the tegmen tympani into the middle cranial fossa can provide a route for the intracranial spread of infection including meningitis, epidural abscess, or intracranial abscess. The loss of supporting bone in the floor of the middle fossa can allow the development of mastoid meningocele, encephalocele, and cerebral spinal fluid leak5 (Fig. 9.4).

Glomus Tumors (Chemodectomas)

Glomus tumors (chemodectomas) are highly vascular, slow-growing tumors that originate from chemoreceptor cells along the parasympathetic nerves. They are named according to their location. If they originate in the bifurcation of the carotid artery, they are known as carotid body tumors. Glomus vagale tumors originate from the vagus nerve in the neck and may extend into the jugular foramen. Glomus tympanicum, the smallest of these tumors, is located in the middle ear, along “Jacobson’s” nerve of cranial nerve IX. Glomus jugulare tumors originate in the jugular bulb and fill or expand the jugular foramen. Glomus jugulare tumors are the most likely to have intracranial extension. Chemodectomas are locally invasive and invade both bone and soft tissue. They frequently present with single or multiple cranial nerve palsies, particularly the lower cranial nerves passing through the jugular foramen.6

Cholesterol Granuloma

A cholesterol granuloma (cholesterol cyst) occurs when an air cell becomes “disconnected” from the pneumatized system and the cell fills with inspissated material. Cholesterol crystals are seen histologically within these cysts and are thought to result from microhemorrhage. As material accumulates within the cell, it slowly expands, often destroying bone. The most common symptom cholesterol granuloma is headache, although large lesions can erode into the otic capsule causing sensorineural hearing loss or dizziness.

Small cholesterol granulomas in the petrous apex are common incidental findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (Fig. 9.5). Only large cysts threatening the inner ear or extending into the posterior fossa require treatment. Treatment consists of establishing a drainage path into the middle ear or mastoid space, but is often difficult to maintain patent. Complete excision of the cyst wall is more difficult because the cyst is often wrapped around the internal carotid or cranial nerves.7 Cholesterol cysts are usually managed by permanently draining them through the middle ear or occasionally through the petrous apex into the sphenoid sinus.

Fig. 9.5 T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating cholesterol granuloma of the petrous apex. (Courtesy of Medlocyclopaedia [http://www.medcyclopaedia.com], Amersham Health.)

Malignant Neoplasms

Malignant neoplasms of the mastoid cavity are very rare. They include primary cancers such as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, lymphoma, and leukemic infiltrates. Metastatic tumor is more common, most often from the lung and breast.8

Cerebral Spinal Fluid Leak and Meningoceles

Breaks in the tegmen tympani, whether secondary to trauma, pseudotumor cerebri, tumor growth, iatrogenic, or a congenital defect, can allow cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage into the mastoid with or without an associated encephalocele (Fig. 9.6). “Spontaneous” CSF otorrhea or an encephalocele should raise the possibility of benign intracranial hypertension.

The CSF may present as otorrhea if there is a breach in the tympanic membrane or as rhinorrhea if the tympanic membrane is intact and the CSF drains into the nasopharynx through the eustachian tube. This latter circumstance has led to the incorrect diagnosis of anterior fossa CSF rhinorrhea and unnecessary craniotomies. When the tympanic membrane is intact, the CSF behind the drum causes a bulging, clear tympanic membrane that may be quite difficult to distinguish from a normal tympanic membrane. Indications of the diagnosis include sluggishness in the movement of the drum on pneumatoscopy and the presence of bubbles behind the drum. CSF otorrhea may also be misdiagnosed as chronic serous otitis media. A tympanostomy tube placed in such an ear yields continuous clear watery drainage. In this instance the tympanostomy tube should be removed before bacteria from the ear canal contaminates the middle ear.

Conservative management with bed rest and lumbar drain is rarely successful except in acute traumatic injuries. Repair usually depends on surgical exploration and correction of the defect with bone and/or fascia graft repair either through the mastoid or small middle fossa craniotomy, depending on the location of the defect.9

Fig. 9.6 Coronal CT with left defect in the tegmen tympani and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid.

Ménière’s Disease

Ménière’s disease is a clinical syndrome consisting of episodic vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and fullness in the ear. These symptoms may be variably present in a given patient. Although the etiology of Ménière’s disease is unknown, ultimately overproduction of endolymph and intermittent rupture of inner ear membranes leads to typical vertiginous attacks. Most patients with Ménière’s disease can be managed medically with a low-sodium (<2 g/day) diet and systemic diuretics. Patients failing medical management, depending on the severity of symptoms and the degree of hearing loss, may be candidates for endolymphatic sac shunt surgery, chemical or surgical labyrinthectomy, or vestibular nerve section.

♦ Surgery of the Mastoid

The goals of otologic surgery are the eradication of disease, the establishment of a safe ear, and the restoration of hearing. The extent of disease in the mastoid dictates whether a conservative or radical approach must be used. A simple or intact canal wall mastoidectomy preserves the external auditory canal and the middle ear. The mastoid cavity remains connected to the middle ear and nasopharynx through the eustachian tube. More extensive disease requires removal of the external auditory canal wall (canal wall down) and marsupializes the mastoid into an enlarged external auditory canal. A modified radical mastoidectomy preserves a shallow middle ear space and conductive mechanism of the middle ear, whereas in a true radical mastoidectomy the eustachian tube is obliterated and the middle ear is sacrificed.

Simple Mastoidectomy (Intact Canal Wall Mastoidectomy)

The key to mastoid surgery is the identification of landmarks, most of which are buried in bone. The sigmoid sinus, facial nerve, and semicircular canals are routinely encountered in mastoid surgery and can be protected only by a thorough knowledge of the three-dimensional interrelationships of these structures in the temporal bone.

Facial nerve monitors are used in most mastoid surgery. Any manipulation or trauma to the nerve generates an auditory signal to the surgeon and operating room staff. A facial nerve stimulator can be used to confirm the identity or location of the nerve. However, monitors can fail or malfunction and are disabled when electrocautery is used; therefore, an absence of a signal from a monitor never absolutely ensures the safety of the nerve. A monitor is never a substitute for thorough knowledge of the anatomic landmarks of the temporal bone.

An incision is made 1 to 2 cm posterior to the postauricular crease and extends from behind the ear lobe to above the ear in the temporal scalp. A flap including the postauricular skin and pinna is developed just superficial to the superficial temporal fascia and mastoid periosteum. The periosteum is divided to expose the mastoid cortex. The upper limit of the mastoid cavity is approximated by the temporal line, which extends posteriorly from the roof of the external auditory canal and the root of the zygoma.

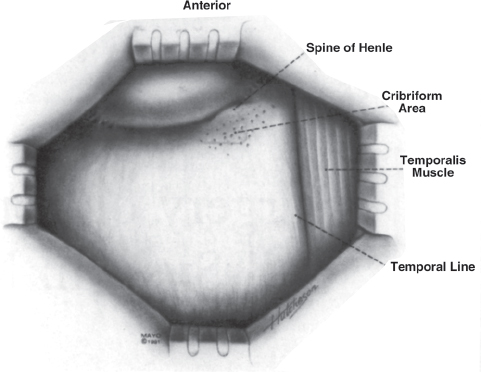

Once the mastoid cortex is exposed, several landmarks guide the dissection: a cribriform area of bone is seen in the postauricular area, the spine of Henle at the posterior border of the external auditory canal, and the external auditory canal itself. Drilling with high-speed drills and constant irrigation is started in a triangle outlined by the temporal line, the spine of Henle, and the cribriform area, known as Macewen’s triangle (Fig. 9.7). Once the outer cortex of bone is removed, mastoid air cells are encountered if the ear has not been chronically infected. Aeration of the mastoid is greatly reduced in a patient who is chronically infected, making dissection more difficult.

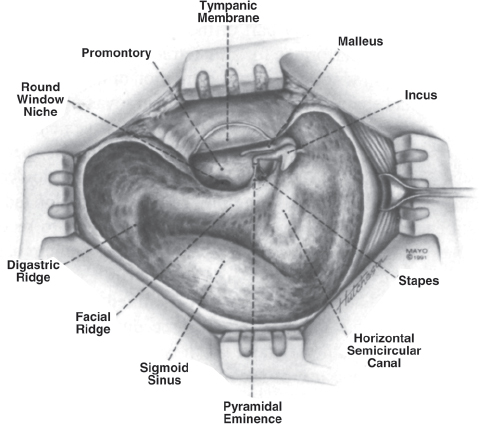

The opening in the mastoid is enlarged until three primary landmarks are identified: the tegmen tympani between the mastoid and the middle cranial fossa, the sigmoid sinus posteriorly, and the external auditory canal anteriorly. A large central mastoid air cell, the mastoid antrum, is the next landmark. The facial nerve, lateral semicircular canal, and the short process of the incus are found in the medial wall of the antrum. If the surgery is being preformed for cholesteatoma, the antrum is frequently filled by the keratocyst, and it must be cleared away to accurately see the landmarks. The facial nerve enters the mastoid cavity inferior to the lateral semicircular canal and then turns inferiorly toward the stylomastoid foramen. The facial nerve may be skeletonized as much as necessary for removal of disease. If necessary, the air cells lying between the facial nerve and the chorda tympani can be removed to provide direct access to the middle ear, round window, and stapes. The opening so created is known as the facial recess. The middle ear can also be approached directly by elevating the external canal skin and tympanic membrane.

Fig. 9.7 Surface landmarks for mastoidectomy. (Courtesy of the Mayo Foundation.)

If the ossicular chain has been damaged by disease or removed to facilitate disease control, the ossicles must be restored to preserve hearing. When the surgery has been straightforward, hearing reconstruction may be performed at the initial setting; however, if the disease is extensive, and particularly when it is infiltrated into numerous mastoid air cells, it is often advisable to delay hearing reconstruction for a second-look procedure 6 to 9 months later. After this delay the tympanic membrane should be stable, and any recurrent disease will have gotten extensive enough to be identifiable.

Modified Radical Mastoidectomy

If the disease cannot be successfully removed with the external auditory canal intact, the posterior wall of the external auditory canal may be removed, resulting in a modified radical mastoidectomy. The only difference in this procedure is the external auditory canal is removed, making the mastoid cavity and the external auditory canal a continuous space open through the external auditory meatus. Because the posterior canal wall does not support the tympanic membrane, it is allowed to drop medially onto the medial wall of the cavity, but a small air-containing middle ear space is maintained. The cavity heals by secondary intention by squamous epithelium migrating over the cavity (Fig. 9.8).

A negative aspect of the canal wall down mastoidectomy is that the patient must have the mastoid cavity cleaned by appropriately trained personnel at regular intervals (6 to 12 months) forever; however, the operation has a higher probability of permanently eradicating disease.

Radical Mastoidectomy

A radical mastoidectomy is similar to a modified radical mastoidectomy, except that the eustachian tube is permanently blocked, the ossicles are removed, and the remnant of the tympanic membrane is allowed to collapse on the medial wall of the middle ear. All remaining air cells and mucosa are removed up to the middle ear and mastoid to form one common cavity. This operation is reserved for the most recalcitrant middle ear and mastoid disease, and permanently closes the door on any kind of surgical hearing restoration, although the patient remains a candidate for a hearing aid (Fig. 9.9).

Fig. 9.8 Mastoid cavity after a modified radical mastoidectomy. (Courtesy of the Mayo Foundation.)

Transmastoid Approaches to the Posterior Fossa

Because a large portion of the mastoid is expendable, it can be removed for access to the deeper portions of the inner ear or posterior fossa. The retrolabyrinthine presigmoid approach preserves the inner ear and can be used for retrolabyrinthine nerve section. The translabyrinthine approach is used for removal of acoustic neuromas.

Retrolabyrinthine Presigmoid Approach

The retrolabyrinthine presigmoid approach provides direct access to the posterior fossa between the anterior edge of the sigmoid sinus and the posterior extent of the otic capsule, primarily the posterior semicircular canal. Because the otic capsule is preserved, there should be no significant change in hearing from this approach. After performing a routine mastoidectomy and identifying the facial nerve and semicircular canals, the anterior edge of the sigmoid sinus is carefully defined. If the access is too small, a “Bill’s island” of bone can be created by circumferentially drilling around the dome of the sigmoid with a diamond bur. The sigmoid can then be safely displaced posteriorly and held with a self-retaining retractor.

Fig. 9.9 Mastoid cavity after a radical mastoidectomy. (Courtesy of the Mayo Foundation.)

The bone is thinned and then removed from the posterior fossa dura between the sigmoid sinus and the otic capsule. The endolymphatic sac may be identified and preserved. The posterior fossa dura is incised lateral to the endolymphatic sac, and the posterior fossa entered. Access to the posterior fossa is adequate for vestibular nerve section and vascular loop decompression of cranial nerve VII or VIII.

Patient selection is important because occasionally a patient will have an anteriorly placed sigmoid, making the retrolabyrinthine approach impossible. This is usually seen in the context of chronic otitis media, but can also occur spontaneously. Axial computed tomography (CT) scans are the easiest way to evaluate the location of the sigmoid sinus.

Translabyrinthine Approach

The translabyrinthine approach has been the workhorse procedure for acoustic neuroma removal for many decades. It provides the closest and most direct route to the posterior fossa for the removal of acoustic neuromas, but with the complete sacrifice of hearing.

The procedure starts with a complete mastoidectomy, with removal of all the mastoid air cells from the middle fossa dura to the mastoid tip, and from the sigmoid sinus to the external auditory canal. The descending portion of the facial nerve is identified and its bony covering preserved. A Bill’s island may be created to allow retraction of the sigmoid sinus if additional exposure is needed.

A complete labyrinthectomy provides access to the internal auditory canal (IAC). The canals are systematically removed and followed to the vestibule. The IAC is located immediately medial to the vestibule; however, it is best approached after removing all bone from the posterior fossa dura medial to the sigmoid and following the dura to the reflection into the IAC. It is important that wide exposure of the IAC be obtained before it is opened; a full 180 degrees of the posterior surface should be exposed before the dura is opened. Inferiorly the exposure should extend well below the IAC, although a high-riding jugular bulb may limit this exposure. Superiorly, the exposure extends to the tegmen and middle fossa dura. Removal of bone behind the sigmoid and up the parietal skull may add exposure if removal of a large tumor is needed.

Middle Fossa Approach

The middle fossa approach affords access to the IAC while preserving the middle ear conductive mechanism, cochlea, and auditory nerve. The middle fossa approach is applicable to small tumors, generally limited to the IAC. To make the effort of attempted hearing preservation worthwhile, the patient must have hearing thresholds of 50 dB and discrimination score of 50% or better

The middle fossa approach is started with a vertical skin incision above the external auditory canal. A small craniotomy enables extradural elevation of the temporal lobe. The floor of the middle fossa has few landmarks and the bony surface may be quite irregular. The goal is to identify the IAC without damage to the facial nerve, superior semicircular canal, and cochlea, all of which are more superficial and partially block the view of the canal. Reliable landmarks include the superior petrosal sinus along the posterior petrous ridge and the middle meningeal artery anteriorly. Several techniques have been described for identification of the IAC. House proposed following the superficial petrosal nerve retrograde to the geniculate ganglion and then tracing the facial nerve to the IAC. Fisch is a proponent of identifying the superior semicircular canal first. An angle of 60 degrees from the superior semicircular canal will fall on the long axis of the internal canal. Lastly, Garcia Ibanez prefers to dissect as far medially in the floor of the middle fossa as possible and then directly identify the IAC medial to all other vital structures.

Regardless of the technique used to find the IAC, it must be opened as widely as possible without violation of the cochlea (anterior) or superior semicircular canal (posterior). The bone around the porus acusticus can be removed to yield limited access to the posterior fossa, but tumors with any significant extension into the posterior fossa are best managed in other ways. Although hearing can be preserved with the middle fossa approach, it does present the technical challenge that the facial nerve lies superficial to the tumor, whereas in the posterior approaches the facial nerve is on the far side of the tumor where it remains relatively protected until the nerve dissection is actually started.

♦ Conclusion

The mastoid is a critical interface between the specialties of neurosurgery and otolaryngology. An understanding of disease processes, surgical techniques, and potential complications is important for both specialties if practitioners are to render optimum care to their patients.

Acknowledgment

We wish to thank Anthony Mattox for photo editing.

References

1. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Management of Acute Otitis Media. Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 2004;113:1451–1465 PubMed

2. Leskinen K, Jero J. Complications of acute otitis media in children in southern Finland. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2004;68:317–324 PubMed

3. is Rubin Grandis J, Branstetter BF IV, Yu VL. The changing face of malignant (necrotising) external otitis: clinical, radiological, and anatomic correlations. Lancet Infect Dis 2004;4:34–39 PubMed

4. Cummings CW. Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 1998:3247–3248

5. Weber PC, Patel S. Jugulotympanic paragangliomas. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2001;34:1231–1240, x PubMed

6. Jaramillo M, Windle-Taylor PC. Large cholesterol granuloma of the petrous apex treated via subcochlear drainage. J Laryngol Otol 2001;115: 1005–1009 PubMed

7. Leonetti JP, Marzo SJ. Malignancy of the temporal bone. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2002;35:405–410 PubMed

8. Brown NE, Grundfast KM, Jabre A, Megerian CA, O’Malley BW Jr, Rosenberg SI. Diagnosis and management of spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid-middle ear effusion and otorrhea. Laryngoscope 2004;114:800–805 PubMed

9. Ervin SE. Meniere’s disease: identifying classic symptoms and current treatments. AAOHN J 2004;52:156–158 PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree