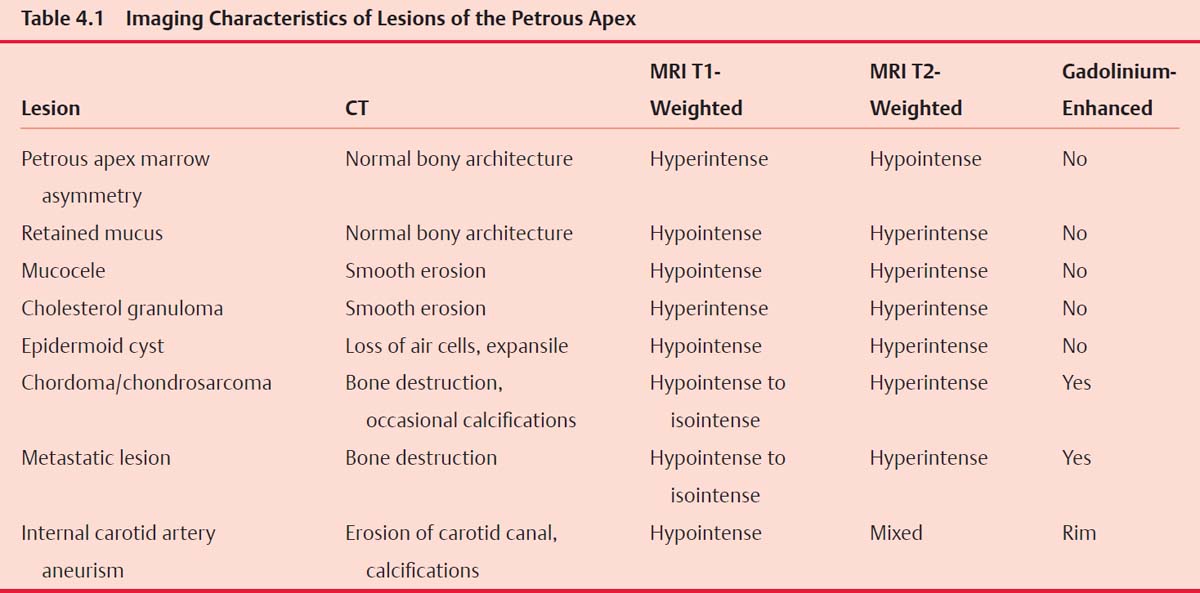

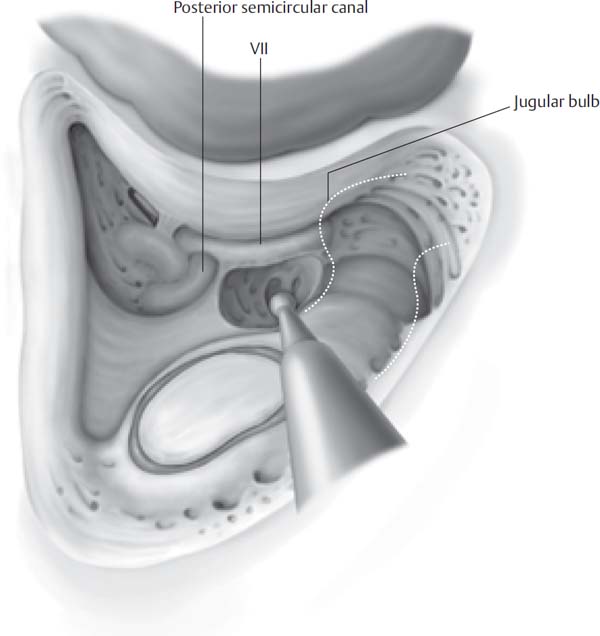

4 Before the antibiotic era, infections were the most common lesions of the petrous apex and they carried a high mortality rate. Fortunately, with the advent of antibiotics, infections of the petrous apex are rarely observed by the neurotologist. Instead, most lesions of the petrous apex are cystic in nature and can be successfully treated with the same drainage procedures previously developed for infections. With the advent of high-resolution computed tomography (CT), the precise location of the lesion and an appropriate approach can be planned. This chapter describes the infralabyrinthine and infracochlear approaches to cystic lesions of the petrous apex. Lesions of the petrous apex present with a wide range of symptoms. The classic presentation of infection of the petrous apex is Gradenigo’s syndrome, which is characterized by the triad of otorrhea, retro-orbital pain, and an ipsilateral abducens nerve palsy. In noninfectious lesions, hearing loss and dizziness are more common presentations. Cystic lesions may occasionally cause facial spasm or paresis, but facial nerve paralysis is more consistent with a neoplastic process. Pain in the form of otalgia, retro-orbital pain, and headaches is a common finding and is dependent on the location of the lesion. Recent advancements in imaging have had a significant impact on the diagnosis and treatment of petrous apex lesions. High-resolution CT gives superb bony detail of the lesion and the surrounding vital structures that dictate the appropriate approach to these lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enhanced with gadolinium contrast gives excellent soft tissue detail and can diagnose most lesions without the need for tissue. Table 4.1 lists the typical appearance of petrous apex lesions on CT and MRI. Approaches to the petrous apex are based on the various air cell tracts of the temporal bone. Air cell tracts superior to the otic capsule can be approached through the middle fossa, superior semicircular canal, the attic, or the zygomatic root. Anterior approaches are based on the air cell tracts between the cochlea, middle fossa dura, and carotid artery. However, the most common contemporary approaches are based on the air cell tracts inferior to the labyrinth and include the infralabyrinthine and infracochlear approaches. Appropriate imaging should be obtained and generally includes both CT and MRI to fully characterize the lesion and surgical approach. A full audiometric evaluation is obtained including air, bone, and speech reception thresholds because it is essential to document preoperative hearing in any procedure that may jeopardize hearing. A videonystagmogram (VNG) is obtained in patients who present with vertigo or imbalance. Patients are counseled regarding the expectations from surgery. It is emphasized that the procedure is a drainage procedure and may not entirely relieve symptoms and may require additional procedures. Preoperative cranial nerve deficits usually improve after drainage of cystic lesions; however, long-standing deficits are less likely to respond to surgery. The choice of approach depends on multiple factors. In patients without serviceable hearing, a translabyrinthine approach provides the safest and most direct access to the petrous apex. In patients with hearing, the infralabyrinthine, infracochlear, or transsphenoidal approaches are appropriate. A high jugular bulb is an obstacle for drainage of petrous apex cysts using the infralabyrinthine approach. The infracochlear approach places the carotid artery at risk and should be attempted by a surgeon with intimate knowledge of the anatomy of the hypotympanum. The infracochlear approach has the advantage of avoiding a mastoidectomy and places the drainage site closer to the eustachian tube. The transsphenoidal approach places the carotid artery and optic nerve at risk; however, the use of intraoperative image guidance has made this approach safer. The boundaries of the infralabyrinthine approach are the posterior semicircular canal superiorly, the jugular bulb and sigmoid sinus inferiorly and posteriorly, and the facial nerve anteriorly. Preoperative imaging should be utilized to determine the position of the jugular bulb because a high jugular bulb may restrict access to the petrous apex through this approach and another approach should be considered. The patient is placed supine with the head turned away from the operative side. Intraoperative facial nerve monitoring is utilized. A standard postauricular incision is made 1 cm posterior to the postauricular sulcus. A second incision is made through the periosteum from the zygomatic root along the linea temporalis and then carried inferior to the mastoid tip. The periosteum is elevated until the posterior extent of the external auditory canal is identified. A simple mastoidectomy is performed and the middle fossa plate, sigmoid sinus, and facial nerve are identified. The sigmoid sinus is followed until the jugular bulb is identified. The superior aspect of the jugular bulb is the inferior limit of this approach. Next the posterior semicircular canal and the posterior half of the lateral semicircular canal are skeletonized, taking care not to expose the membranous labyrinth. Once the jugular bulb and posterior semicircular canal have been identified, the air cell tracts are followed using diamond burs and curettes until the cystic lesion is entered (Fig. 4.1). The opening is widened using the anatomic limits, and all loose debris is removed from the cyst using suction and irrigation. The largest silicone tubing possible is placed in the surgical tract to prevent stenosis (Fig. 4.2). The periosteum is reapproximated using absorbable sutures, and the skin is closed in the standard fashion. A pressure dressing is placed and left in place for 24 hours. Fig. 4.1 The posterior lateral semicircular canal, posterior semicircular canal, and jugular bulb have been identified and are the boundaries of the approach.

The Infracochlear/Infralabyrinthine Approach to the Petrous Apex

Evaluation

Evaluation

Preoperative Workup

Preoperative Workup

Infralabyrinthine Approach to the Petrous Apex

Infralabyrinthine Approach to the Petrous Apex

Surgical Anatomy

Surgical Technique

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree