The Spinal Accessory Nerve

The spinal accessory (SA) nerve, cranial nerve XI (CN XI), is actually two nerves that run together in a common bundle for a short distance. The smaller cranial portion is a special visceral efferent accessory to the vagus. The cranial root exits through the jugular foramen separately from the spinal portion then blends with the vagus. It is distributed principally with the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The major part of CN XI is the spinal portion. The fibers of the spinal root arise from motor cells in the SA nuclei in the ventral horn from C2 to C5, or even C6. Its axons emerge as a series of rootlets laterally between the anterior and posterior roots. These unite into a single trunk which ascends between the denticulate ligaments and the posterior roots. The nerve enters the skull through the foramen magnum, ascends the clivus for a short distance, then curves laterally. The spinal root joins the cranial root for a short distance, probably receiving one or two filaments from it. It exits through the jugular foramen in company with CNs IX and X.

The supranuclear innervation of CN XI arises from the lower portion of the precentral gyrus. Fibers from the lateral corticospinal tract in the cervical spinal cord communicate with the SA nucleus. There is some controversy, but the bulk of current evidence indicates that both the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) and trapezius receive bilateral supranuclear innervation, but the input to the SCM motor neuron pool is predominantly ipsilateral and that to the trapezius motor neuron pool is predominantly contralateral. The SCM turns the head to the opposite side, and its supranuclear innervation is ipsilateral; therefore the right cerebral hemisphere turns the head to the left.

Examination of the Spinal Accessory Nerve

The functions of the cranial portion of CN XI cannot be distinguished from those of CN X, and examination is limited to evaluation of the functions of the spinal portion. One SCM acts to turn the head to the opposite side or to tilt it to the same side. Acting together, the SCMs thrust the head forward and flex the neck. The muscles should be inspected and palpated to determine their tone and volume. The contours are distinct even at rest. With a nuclear or infranuclear lesion there may be atrophy or fasciculations.

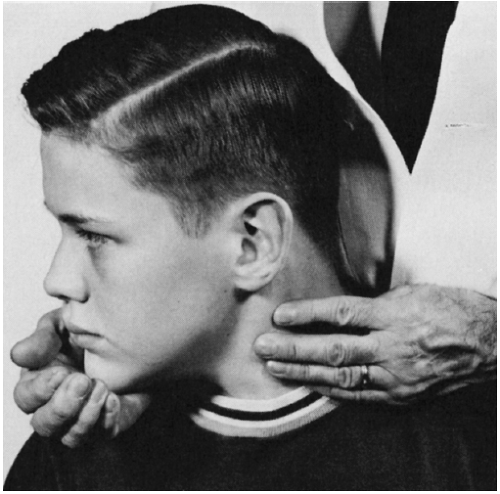

To assess SCM power, have the patient turn the head fully to one side and hold it there, then try to turn the head back to midline, avoiding any tilting or leaning motion. The muscle usually stands out well, and its contraction can be seen and felt (Figure 15.1). Unilateral SCM paresis causes little change in the resting position of the head. Even with complete paralysis, other cervical muscles can perform some degree of rotation and flexion; only occasionally is there a noticeable head turn.

FIGURE 15.1 • Examination of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. When the patient turns his head to the right against resistance, the contracting muscle can be seen and palpated. |

With bilateral paralysis of CN XI innervated muscles there is diminished but not absent neck rotation, and the head may droop or even fall backward or forward, depending upon whether the SCMs or the trapezei are more involved. The two SCM muscles can be examined simultaneously by having the patient flex his neck while the examiner exerts pressure on the forehead, or by having the patient turn the head from side to side. Flexion of the head against resistance may cause deviation of the head toward the paralyzed side. With unilateral paralysis, the involved muscle is flat and does not contract or become tense when attempting to turn the head contralaterally or to flex the neck against resistance. Weakness of both SCMs causes difficulty in anteroflexion of the neck, and the head may assume an extended position.

With trapezius atrophy the outline of the neck changes, with depression or drooping of the shoulder contour and flattening of the trapezius ridge (Figure 15.2). Severe trapezius weakness causes sagging of the shoulder, and the resting position of the scapula shifts downward. The upper portion of the scapula tends to fall laterally, while the inferior angle moves inward. This scapular rotation and displacement are more obvious with arm abduction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree