Chapter 46 Translabyrinthine Approach to Vestibular Schwannomas

Vestibular schwannomas can be surgically accessed via a subtemporal, a translabyrinthine, or a suboccipital and retrosigmoid approach.1,2 The number of centers that have mastered all approaches has increased. The translabyrinthine approach was reintroduced approximately 35 years ago3 and is successfully used by several otologic specialist centers.4–6 After developments in skull base surgery, neurosurgeons have become aware of the advantages of the translabyrinthine approach for vestibular schwannomas and for other skull base lesions.

Advantages of the Translabyrinthine Approach

It has been stated that the usefulness of the translabyrinthine approach is limited to small tumors. In fact, no tumor is too large to be approached by the translabyrinthine route.7–9 In large and giant tumors, it is a significant advantage to be able to go directly to the center of the tumor; after debulking the center of the tumor, the neoplasm collapses and is displaced toward the opening by the surrounding brain structure.

Disadvantages of the Translabyrinthine Approach

The translabyrinthine procedure destroys the labyrinth and, as a consequence, hearing. This approach is not used if preservation of hearing is attempted. Only a limited number of patients with vestibular schwannomas have hearing worth preserving, however. If the tumor exceeds 2 cm in size, the chances of preserving hearing are known to be poor.10

Surgical Anatomy

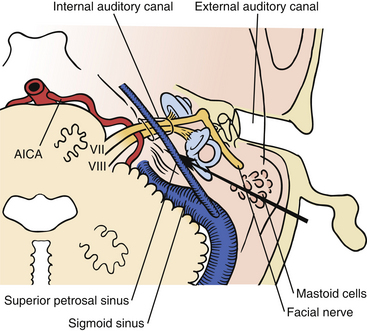

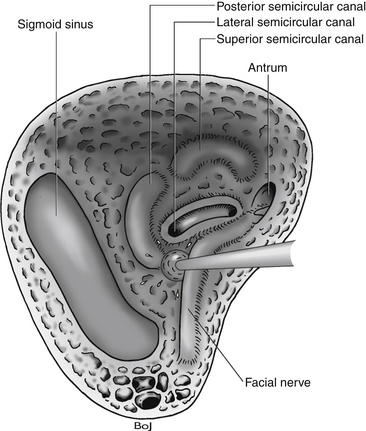

The bone opening for the translabyrinthine approach is done in the mastoid part of the temporal bone (Fig. 46-1). The mastoid is filled with air cells, and the air cells are connected to the middle ear through the tympanic antrum. In the translabyrinthine approach, the bone is removed between the sigmoid sinus and the external ear canal. The sigmoid sinus is located in the sigmoid sulcus in the temporal bone. From the posterior aspect of the sigmoid sinus, emissary veins run through the mastoid foramen to subgaleal veins.11–13

Removing the air cells creates a space that is bounded posteriorly by the wall of the sigmoid sulcus, superiorly by the tegmen tympani, and anteriorly by the prominence of the lateral semicircular canal. Above the prominence of the lateral semicircular canal, the antrum communicates with the tympanic cavity. The facial canal runs close to the mastoid wall of the tympanic cavity. The genu of the facial canal is just inferior to the lateral semicircular canal, and it continues inferiorly to emerge below the skull base at the stylomastoid foramen (Fig. 46-2). The sigmoid sulcus meets the roof of the cavity at a sharp sinodural angle from which the superior petrosal sulcus runs anteriorly. When removing the bone in the sinodural angle, the superior petrosal sinus is exposed in a dural duplex.

FIGURE 46-2 Relationship of the labyrinth, the internal acoustic canal, the facial nerve, and the sigmoid sinus.

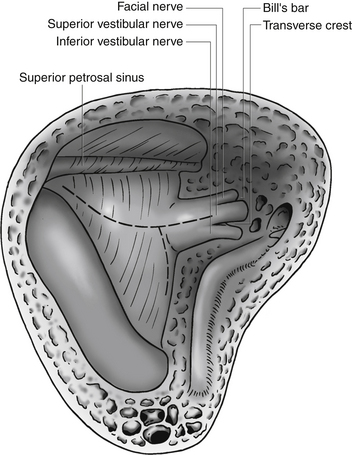

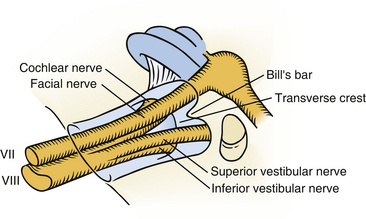

The lateral semicircular canal is an important landmark for the location of the entire labyrinth. After removing all three semicircular canals, the vestibule is open. The vestibule is the bone cavity that harbors the soft-tissue part of the labyrinth utricle and saccule. Through the aperture of the vestibular aqueduct runs the endolymphatic duct that connects the utricle to the endolymphatic sac. The internal auditory canal contains four separate nerves: two vestibular nerves, the facial nerve, and the cochlear nerve. Located laterally are the superior and inferior vestibular nerves separated at the fundus by a bony crest called the transverse crest. Anterior to the superior vestibular nerve, the facial nerve enters the fallopian canal. Laterally, the facial nerve is separated from the superior vestibular nerve by a small vertical bony septum called the vertical crest or Bill’s bar (Fig. 46-3).

FIGURE 46-3 Contents of the internal acoustic canal, which shows the relation of the facial nerve to Bill’s bar.

Preparation for Surgery

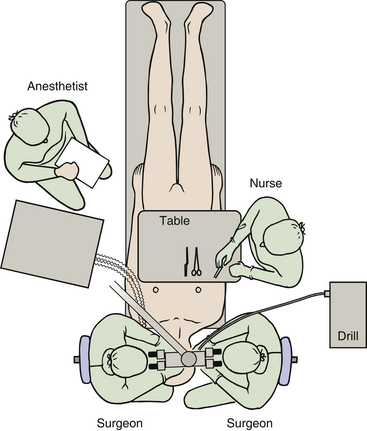

A cephalosporin is given intravenously just before surgery and repeated every 3 hours. The patient is placed in a supine position on the operating table. The patient’s head is turned toward the opposite side and maintained in position with a Sugita head frame. Excessive rotation of the head should be avoided because it may cause venous obstruction in the neck. Decreased mobility of the neck in elderly patients may make sufficient rotation of the head difficult to achieve. This problem may be solved by lifting the ipsilateral shoulder with a pillow and by rotating the whole table.

Continuous electrophysiologic monitoring of facial nerve function is performed during the operation.14–16 This monitoring has become an established procedure and is mandatory in my operations. To accomplish this, electrodes are placed in the frontal and oral orbicular muscles. We use a floor-standing operating microscope with the two surgeons sitting opposite each other on each side of the patient’s head. This setup enables both surgeons to be in a comfortable sitting position with a direct view in the microscope. The lead surgeon sits on the same side as the tumor. In left-sided tumors, the drill is placed between the two surgeons, and in right-sided tumors, the drill is placed between the scrub nurse and the surgeon on the right side (Fig. 46-4). The anesthesiologist is placed at the lower left side of the table at the level of the hip of the patient.

Surgical Procedure

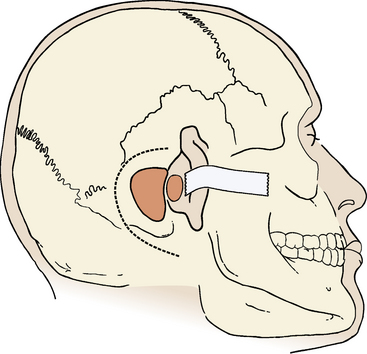

Although some surgeons advocate routine cannulation of the lateral ventricle to relieve hydrocephalus or prevent surgically induced hydrocephalus, I do not find this necessary because, even in large tumors, it is easy to access the cistern magna beneath the tumor, open the arachnoid, and allow cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to drain. The skin incision is made using the cutting cautery to decrease the amount of bleeding from the skin. The incision starts at the upper edge of the helix, superior to the linea temporalis; it continues 4 to 5 cm posteriorly, turns inferiorly, and ends near the tip of the mastoid process (Fig. 46-5).

Mastoidectomy

An extended mastoidectomy is performed with removal of bone over the sigmoid sinus and the middle cranial fossa (Fig. 46-5). In cases with an anteriorly placed sigmoid sinus or large tumors, I also remove bone over the posterior cranial fossa behind the sigmoid sinus.17,18 The extended bone removal ensures good visualization of the entire surgical field. The power drill, driven by either an electric motor or an air turbine, is an essential tool in the translabyrinthine procedure. The cortical bone covering the mastoid region is removed by a large cutting drill. In cases with pronounced pneumatization, a large hole can be made quickly and safely. The anterior margin for cortical bone removal is just behind the external ear canal. The opening is gradually widened backward to the sigmoid sinus and upward to the dura in the middle cranial fossa. Removal of bone over the sigmoid sinus must be done carefully. If the cutting drill tears the sigmoid sinus, profuse bleeding ensues, requiring packing with Surgicel or direct suture of the sinus wall. Large emissary veins often drain into the posterior aspect of the sigmoid sinus. They can be identified through the bone as it is removed. The emissary veins must be controlled with bipolar coagulation and are filled with bone wax. With a drill, the sigmoid sinus is skeletonized.

The method recommended by House and Hitselberger19 is to leave a small island of bone (Bill’s island) over the sigmoid sinus to protect the surface from the trauma of retraction. With a diamond drill, the bone around the outlined island is removed, leaving a part of the sinus wall with an oval piece of bone. The sinus wall and the bony island can then be depressed, and the sinus wall that corresponds to the bony island is protected. I find this method less appropriate because of the risk of lesions in the sinus wall that may be produced by the sharp edge of the bony island.

Labyrinthectomy

It is essential to open the antrum and to identify the lateral semicircular canal (Fig. 46-6). This canal is a main landmark, and once the positions of this canal and of the antrum are known, the three-dimensional anatomy of the facial nerve is known. After identification of the facial nerve, the labyrinthectomy is performed. The bone in the sinodural angle is removed, followed by opening along the superior petrosal sinus until the labyrinthine bone is encountered. The lateral semicircular canal is drilled away until the ampulla is reached anteriorly. Then the posterior and superior semicircular canals are identified and removed to their entrance in the vestibule. After opening of the vestibule, the facial nerve is skeletonized from the genu inferiorly to near the stylomastoid foramen. It is not necessary to remove all bone around the nerve. I always make a small window in the fallopian canal near the second genu to ensure the position of the nerve and to ensure correct function of the facial nerve monitoring device. To avoid injury to the facial nerve, a thin, eggshell bone is left on the nerve. Only posteriorly, where access is needed to approach the cerebellopontine angle, is the nerve exposed.

FIGURE 46-6 The facial nerve and the sigmoid sinus have been skeletonized. The lateral semicircular canal is opened.

Internal Auditory Canal Dissection

All bone between the internal meatus and the jugular bulb is removed. The location of the jugular bulb is extremely variable. When its position is low, all bone removal necessary for tumor removal can be performed without seeing the jugular bulb. In other cases, its position is high and occurs as a bluish spot in the bone after removing the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal. The surgeon should always be aware of the blue color of the jugular bulb when drilling medial to the facial nerve and inferior to the posterior semicircular canal. All bone covering the jugular bulb must be removed in cases with a high-positioned jugular bulb, in which the bulb is an obstacle to proper bone removal from the inferior aspect of the internal acoustic meatus.

The facial nerve often underlies the dura along the anterior–superior aspect of the internal auditory canal, and extreme care must be taken not to allow the bur to slip into the canal. The facial nerve is especially vulnerable at this point. The lateral end of the internal auditory canal is divided by the transverse crest in an inferior and a superior compartment (Fig. 46-7). The bone around the inferior compartment can be drilled away to the most lateral extent of the canal without risk of facial nerve injury. In the superior compartment, bone removal allows identification of a bar of bone (Bill’s bar), which separates the superior vestibular nerve from the facial nerve. The bone is removed at the porus and the medial part of the internal auditory canal first; the more difficult lateral part is left until last, when most of the bone removal has been completed.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree