19 Ulnar Neuropathy at the Elbow

Anatomy

The ulnar nerve is essentially derived from the C8 and T1 roots (Figure 19–1), although some anatomic dissections have also demonstrated a minor component from C7. Accordingly, nearly all ulnar fibers travel through the lower trunk of the brachial plexus and then continue into the medial cord. The terminal extension of the medial cord becomes the ulnar nerve. The medial brachial and medial antebrachial cutaneous sensory nerves and a large contribution to the median nerve are derived from the medial cord as well. As the ulnar nerve descends through the medial arm, it does so without giving off any muscular branches. The ulnar nerve pierces the medial intermuscular septum in the mid-arm and then passes through the arcade of Struthers, which is composed of deep fascia, muscle fibers from the medial head of the triceps, and the internal brachial ligament. The ulnar nerve then travels medially and distally toward the elbow.

FIGURE 19–1 Ulnar nerve anatomy.

(Reprinted with permission from Haymaker, W., Woodhall, B., 1953. Peripheral nerve injuries. WB Saunders, Philadelphia.)

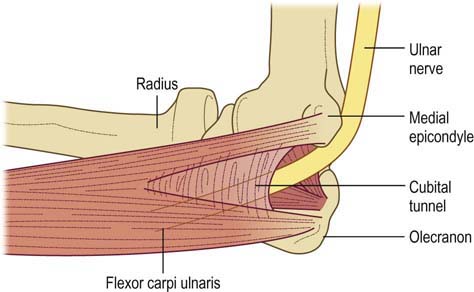

Detailed Anatomy at the Elbow

As the nerve approaches the ulnar groove, it becomes quite superficial (Figure 19–2). The ulnar nerve normally runs in the groove formed by the medial epicondyle of the humerus and the olecranon process of the ulna. In some individuals, fully flexing the elbow may allow the ulnar nerve to sublux out of the groove medially over the medial epicondyle. In a small number of individuals, a dense fibrotendinous band or an accessory epitrochleoanconeus muscle (or both) may be present between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon process. Just distal to the groove is the HUA (cubital tunnel).

FIGURE 19–2 Detailed ulnar nerve anatomy at the elbow.

(Reprinted with permission from Kincaid, J.C., 1988. AAEE minimonograph no. 31: the electrodiagnosis of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Muscle Nerve 11, 1005.)

Clinical

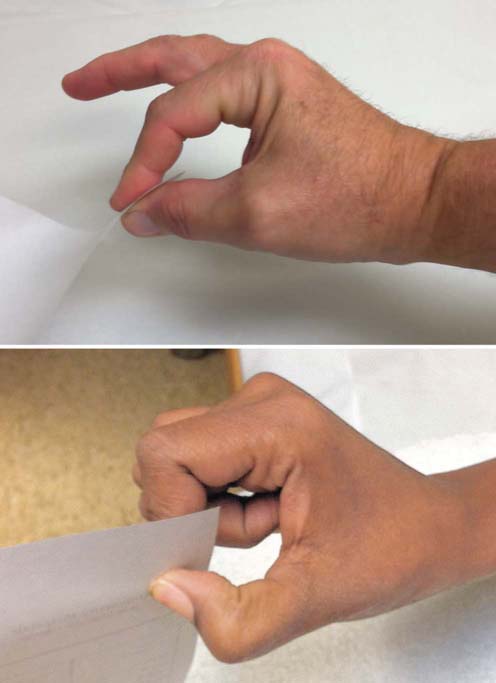

In moderate or advanced cases, examination often shows the classic hand postures that occur with ulnar muscle weakness. The most recognized is the Benediction posture (Figure 19–3). The ring and little fingers are clawed, with the metacarpophalangeal joints hyperextended and the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints flexed (from third and fourth lumbrical weakness), while the fingers and thumb are held slightly abducted (from interossei and adductor pollicis weakness). The Wartenberg’s sign is recognized as a passively abducted little finger due to weakness of the third palmar interosseous muscle (Figure 19–4). The clinical correlate to this sign is that the patient reports getting the little finger caught when trying to put their hand in their pocket. The Froment’s sign occurs when the patient attempts to pinch an object or a piece of paper (Figure 19–5). To compensate for intrinsic ulnar hand weakness, the long flexors to the thumb and index finger (median innervated) are used, creating a flexed thumb and index finger posture.

Examination of the patient’s grip often reveals it to be abnormal. Weakness of the ulnar-innervated FDP will result in the inability to flex the joints of the ring and little fingers. This often can be demonstrated just by having the patient make a fist (Figure 19–6). Patients with ulnar neuropathy may not be able to flex the distal fourth and fifth fingers completely when making a grip; in contrast, the median-innervated second and third distal digits flex normally.

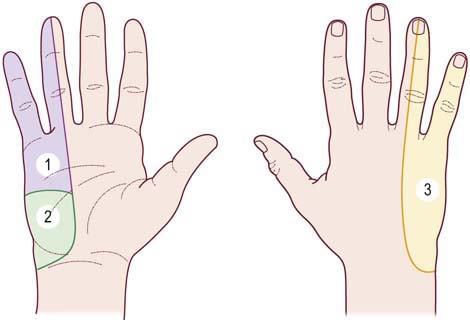

In UNE, sensory disturbance, when present, involves the volar and dorsal fifth and medial fourth digits and the medial hand (Figure 19–7). The sensory disturbance does not extend proximally much beyond the wrist crease. Sensory involvement extending into the medial forearm implies a higher lesion in the plexus or nerve roots (i.e., this is the territory of the medial antebrachial cutaneous sensory nerve, which arises directly from the medial cord of the brachial plexus). Another important skin territory to check is the dorsal medial hand. Sensory abnormalities here are important because they indicate that the dorsal ulnar cutaneous sensory nerve territory also is involved. This finding excludes an ulnar neuropathy at the wrist as the dorsal ulnar cutaneous sensory nerve arises proximal to the wrist.

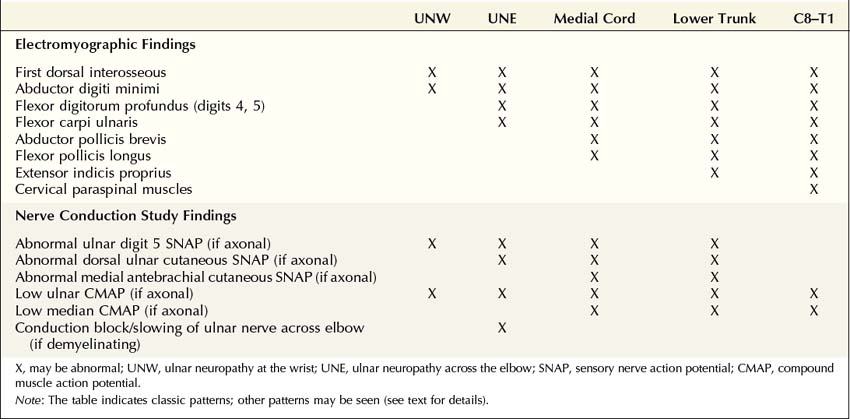

Differential Diagnosis

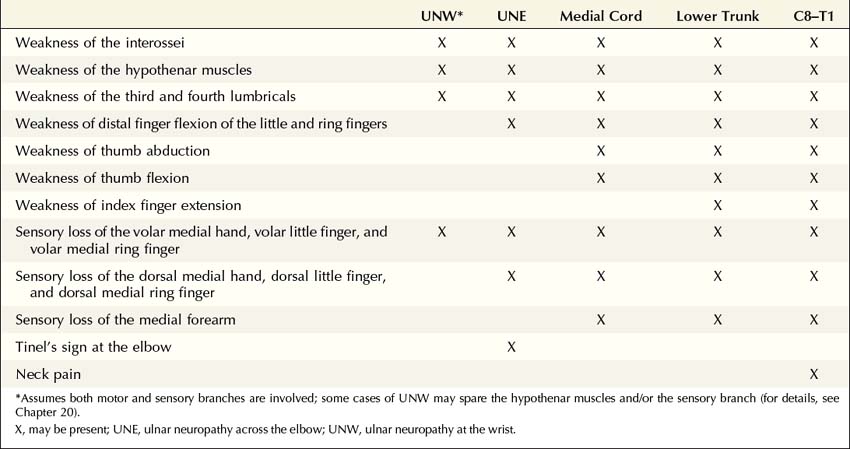

The differential diagnosis in a patient suspected of having UNE (Table 19–1) principally includes C8–T1 radiculopathy, lower trunk or medial cord brachial plexopathy, and ulnar neuropathy at the wrist. Very rare cases of ulnar nerve entrapment in the proximal arm and more distally in the forearm have also been reported.

Lower trunk/medial cord brachial plexopathies are uncommon. Entrapment of the lower trunk by a fibrous band or hypertrophied muscle results in neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (see Chapter 30). Lower trunk plexopathies may also result from infiltration by neoplasm, prior radiation, or self-limited inflammatory processes (e.g., neuralgic amyotrophy). Like C8–T1 radiculopathy, lower trunk plexopathies may demonstrate weakness of non-ulnar-innervated C8–T1 muscles and sensory disturbance that extends into the medial forearm.

Electrophysiologic Evaluation

Like other mononeuropathies, the goal of nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG) is to demonstrate abnormalities that are limited to one nerve, in this case the ulnar nerve. Although in most cases the lesion is at the elbow, entrapment at the wrist, at the medial cord or lower trunk of the brachial plexus, or at the C8–T1 nerve roots can mimic a UNE clinically. Patterns of nerve conduction and EMG abnormalities often can be used to differentiate these possibilities (Table 19–2). If the ulnar nerve lesion is demyelinating, nerve conduction studies may demonstrate conduction velocity slowing, conduction block, or both at the lesion site. Unfortunately, in many cases of UNE, the pathophysiology is that of axonal loss, and nerve conduction studies demonstrate only a non-localizable ulnar neuropathy. The EMG study, if abnormal, then can be used to localize the lesion only at or proximal to the takeoff to the most proximal muscle affected on EMG. Because there are no ulnar-innervated muscles above the elbow, the electrophysiologic impression often is one of an ulnar neuropathy at or proximal to the FCU muscle (the most proximal ulnar-innervated muscle).

Table 19–2 Electromyographic and Nerve Conduction Study Abnormalities Localizing the Lesion Site in Ulnar Neuropathy

Nerve Conduction Studies

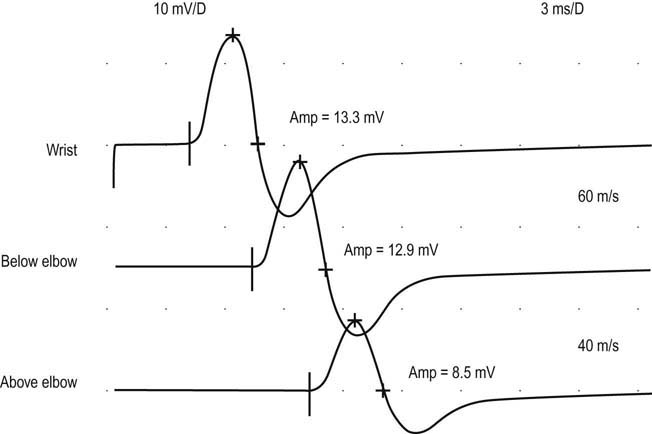

The goal of nerve conduction studies in patients with UNE is to demonstrate, when possible, focal demyelination across the elbow (Box 19–1). Focal demyelinating lesions may manifest as slowing of conduction velocity or conduction block between proximal and distal stimulation sites (Figure 19–8). As for focal slowing, one needs to consider how much slowing is abnormal. In general, conduction velocities of more proximal nerve segments are the same as, or more often faster than those of, distal segments. This is due to a combination of (1) larger nerve fiber diameter and less tapering of the nerve more proximally (the reason that conduction velocities are faster in the upper than in the lower extremity) and (2) warmer temperatures in the proximal limb compared to the distal limb. In ulnar motor nerve conduction studies, however, this relationship may not hold true unless the position of the elbow is controlled.

Box 19–1

Recommended Nerve Conduction Study Protocol for Ulnar Neuropathy at the Elbow

1. Ulnar motor study recording abductor digiti minimi, stimulating wrist, below elbow, and above elbow in the flexed elbow position (note: the optimal site for stimulating at the below-elbow site is 3 cm distal to the medial epicondyle)

2. Median motor study recording abductor pollicis brevis, stimulating wrist and antecubital fossa

3. Median and ulnar F responses

4. Ulnar sensory response, recording digit 5, stimulating wrist

5. Median sensory response, recording digit 2 or 3, stimulating wrist

6. Radial sensory response, recording snuffbox, stimulating lateral forearm

The following patterns may result:

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow with demyelinating and axonal features:

• Normal or low-amplitude ulnar CMAP with normal or slightly prolonged distal latency.

• Unequivocal evidence of demyelination at the elbow (conduction block and/or slowing >10–11 m/s across the elbow compared with the forearm segment, in the flexed elbow position).

Ulnar neuropathy at the elbow with pure demyelinating features:

• Normal distal ulnar SNAP and CMAP amplitudes and latencies.

• Unequivocal evidence of demyelination at the elbow (conduction block and/or slowing >10–11 m/s across the elbow compared with the forearm segment, in the flexed elbow position).

Non-localizable ulnar neuropathy (axonal features alone):

If the ulnar neuropathy is non-localizable, the following studies should be considered:

• Repeat motor studies recording the first dorsal interosseous.

• Inching studies across the elbow.

• Sensory or mixed nerve studies across the elbow.

• Recording the dorsal ulnar cutaneous SNAP (bilateral studies) (remember that the dorsal ulnar cutaneous SNAP can be normal in some patients with ulnar neuropathy across the elbow).

• Recording the medial antebrachial cutaneous SNAP (bilateral studies) if sensory loss extends above the wrist on clinical examination or there is a suggestion of lower brachial plexus lesion by history.

CMAP, compound muscle action potential; SNAP, sensory nerve action potential.

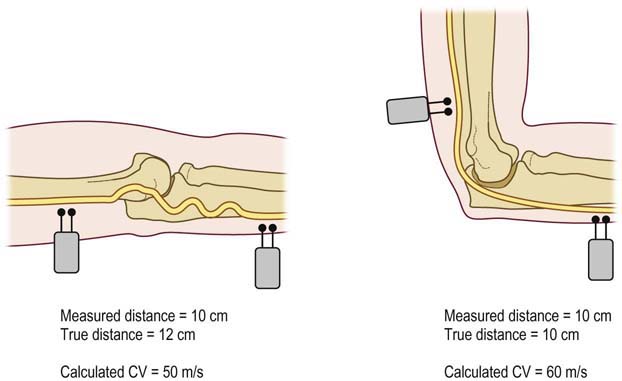

Differential Slowing: Flexed versus Extended Elbow Conduction Techniques

One of the more complicating factors in ulnar conduction studies is the position of the elbow and its effect on the calculated conduction velocity across the elbow. It has been well established in many studies that the position of the elbow during ulnar conduction studies strongly influences the calculated conduction velocity. Ulnar conduction studies performed in the extended (i.e., straight) elbow position often show artifactual slowing of conduction velocity across the elbow due to underestimation of the true nerve length (Figure 19–9). This is because in the extended elbow position, the ulnar nerve is slack with some redundancy. In normal subjects, this results in ulnar conduction velocities being slower in the across-the-elbow segment than in the segment above or below it, if the study is performed with the elbow in the extended position. Autopsy studies have confirmed that the length of the ulnar nerve across the elbow is measured more accurately with the elbow flexed (i.e., bent).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree