Vascular Anatomy of the Spine and Spinal Cord

As stated in the previous chapter, the development of the adult aortic, extracranial, and intracranial vascular networks requires an incalculable number of steps in both the embryonic and postnatal phases. The development of the vascular anatomy of the spine and spinal cord is no different. Variants in anatomical structure in the spine and spinal cord vasculature are also very common and are often unrecognized due to the redundancy of the vascular supply. As is the case with the vasculature of the head and neck, knowledge of the intimate details of the embryologic development of the spinal vasculature will rarely be necessary, so the descriptions below involve only the fundamentals of these processes. Further details should be gleaned from texts specifically written on the topic of spine and spinal cord vascular anatomy.

Early Development of Spinal Vasculature (<6 Weeks)

Until the third week of embryogenesis, 31 pairs of somites, which are segmental masses of mesoderm, develop and migrate toward the midline of the neural tube. Once reaching this phase, the somites fuse and then separate into cranial and caudal halves (Fig. 2.1). The caudal portion of the somite above fuses with the cranial portion of the somite below, leading to the development of the vertebral bodies. The intervertebral disc is formed from the remnant of the cranial-caudal division of the somite.

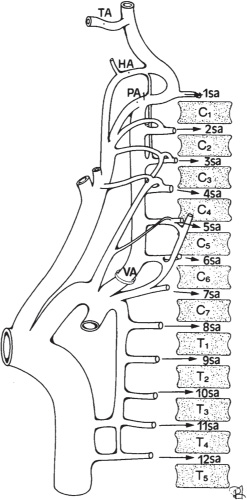

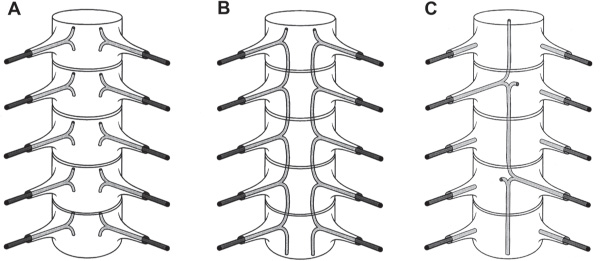

Each somite receives one pair of arteries, that is, the segmental arteries, which originate from the dorsal aorta (Fig. 2.2). Each segmental artery supplies blood to the corresponding ipsilateral metamer (neural crest, neural tube, and somites): skin, muscle, bone, spinal nerve, and spinal cord.1 The segmental arteries subsequently divide into several divisions: (1) the ventral radiculo-medullary, supplying the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord and (2) the dorsal radiculo-pial artery that supplies the epidural structures, dura mater and posterior third of the spinal cord (Fig. 2.3). The dorsal pial network (an anastomotic network of arteries that surround the spinal cord) eventually forms the bilateral posterolateral arteries to the spinal cord (Fig. 2.4).

These early stages, 3 to 6 weeks after gestation, of vascular development in and around the spinal cord are thought to be a time when vascular malformations are initiated. As the longitudinal venous channels form along both the ventral and dorsal surfaces of the spinal cord, other arterial anastomoses occur along the dorsal surface, giving an opportunity for variations in anatomical formation. Approximately 20% of those individuals harboring spinal vascular malformations have either other systemic vascular malformations or vascular malformations throughout the spinal axis. As discussed later in this handbook, spinal vascular malformations are most commonly classified into several groups, differentiated by their location, whether intradural, extradural, at the conus, or in various combinations.

Fig. 2.2 Development of the central ventral artery. (A) Metameric stage, where one artery follows the spinal nerve to supply the corresponding neural tube. (B) Development of the longitudinal network through anastomosis of the metameric homologues. (C) The central ventral artery is formed through fusion and desegmentation. (With kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A, ter Brugge K. Surgical Neuroangiography, 2nd ed. Springer; 2004:73–164.)

Spinal Cord Blood Supply (6 Weeks to 4 Months)

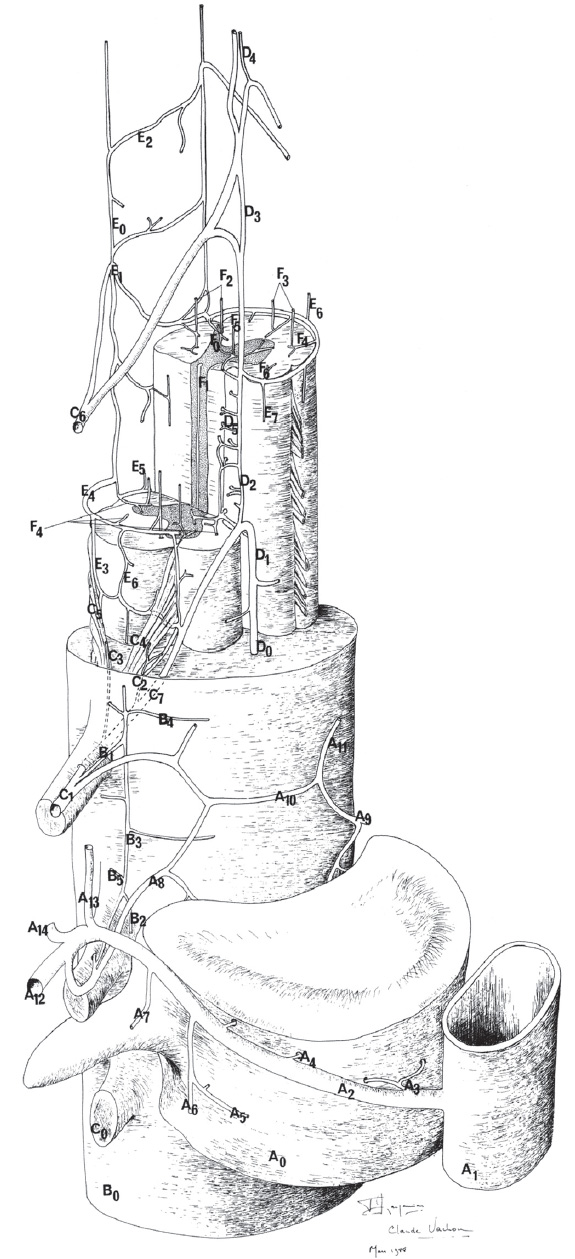

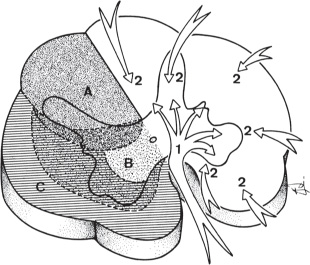

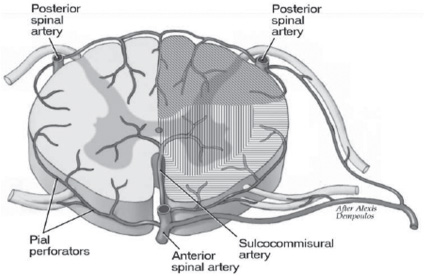

Prior to the midline ventral formation of the anterior spinal artery, each longitudinal ventral neural axis provides several arterial branches, which run longitudinally and deep within the ventral sulcus and supply the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. These arteries provide the penetrating perforators into the spinal cord (sulcal arteries) (Fig. 2.5), known as the centrifugal system of Adamkiewicz.2,3 At the cervical and lumbar enlargements, these sulcal arteries supply nearly half of the blood to the spinal cord proper, while the other half is supplied by direct ventral and pial sources (Fig. 2.6). In the thoracic region, the vast majority of the blood supply is derived from the ventral neural axis and pial network, not from the sulcal arteries.4

In conjunction with the development of the sulcal arteries, regression of the radicular arteries begins to take place as the axial organization of the spinal vasculature evolves into a longitudinal orientation. Thus, only 4–8 ventral radicular arteries and 10–20 dorsal radicular arteries remain at 4 months.5 These remaining radicular arteries supply the entire radiculo-medullary and radiculo-pial networks. Nonfusion of the paired ventral arteries can occur during these processes, and the arteries end up as fenestrated or unfused arteries. Radiographically, they have a characteristic “diamond” shape at that segment.6

Within the spinal canal, longitudinal anastomotic channels form the specific vascular structures listed in Table 2.1.

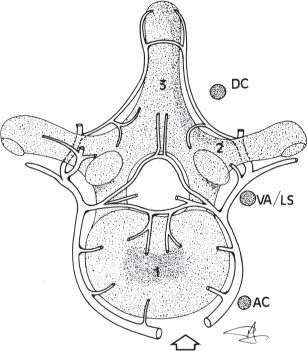

Fig. 2.4 Axial view of longitudinal spinal arterial supply: (1) vertebral body, (2) transverse process, (3) spinal process, (AC) ascending cervical artery, (VA) vertebral artery, (LS) lateral sacral artery, and (DC) deep cervical artery. (With kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A, ter Brugge K. Surgical Neuroangiography, 2nd ed. Springer: 2004:73–164, Fig. 2.15.)

Fig. 2.5 Axial distribution of spinal cord arterial supply. The sulcocommissural (1,B) and radial (2,A,C) supply the spinal cord with multiple areas of overlap. (With kind permission from Springer Science+Business Media: Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A, ter Brugge K. Surgical Neuroangiography, 2nd ed. Springer; 2004:73–164, Fig. 2.76.)

Fig. 2.6 Vascular territories of the anterior and posterior spinal arteries. (With kind permission from Elsevier: Wells-Roth D, Zonnenshayn M. Vascular anatomy of the spine. Operative Techniques in Neurosurgery Sept 2003;6(3):116–121, Fig. 5.)

Table 2.1 Developing Arteries and Their Origins

Artery of origin | Developing artery |

Cervical vertebral arteries | Anterior spinal artery |

Subclavian and/or supreme intercostal arteries | Upper thoracic intercostals (T2–T5) |

Internal iliac arteries | Lateral sacral arteries |

Caudal dorsal aorta | Middle sacral artery |

Adult Spinal Arterial Anatomy

Spinal Arteries

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree