Brain CT showing two cortical strokes (left frontal lobe and right parieto-frontal lobe) and several subcortical vascular lesions.

Discussion

This patient had recurrent strokes and imaging evidence of severe vascular brain involvement beyond two clinically evident stroke episodes. She could represent the old concept of “multi-infarct dementia.” She had some minor cognitive sequel from each clinical stroke, but progressive cognitive deterioration started a few years after the last clinical stroke. The first question posed by the daughters was “did she have a new stroke?” The clinical picture was not suggestive of a new stroke and brain imaging did not show new lesions. Laboratory evaluation did not show concomitant metabolic comorbidity that could explain her clinical deterioration observed over the previous months. Slow progression of the picture before hospitalization, stability of the clinical status after admission, and absence of other changes in brain imaging and EEG did not become suspicious of other etiologies (as for instance encephalitis). She did not have a depressive episode to explain the neuropsychological deficits. Furthermore, the neuropsychological deficits were not suggestive of a concomitant degenerative disorder as Alzheimer’s disease; instead, they were more compatible with vascular cognitive impairment. Traditional criteria for vascular dementia implicate the following key elements: (1) cognitive impairment enough to implicate functional impairment and loss of autonomy; (2) evidence of cerebrovascular disease; and (3) a relationship between the cognitive deficit and the cerebrovascular disorder [1]. The relationship between cerebrovascular disease and cognitive impairment is usually defined in classical clinical criteria by a temporal relationship, and evolution should be sudden, with stepwise progression. However, vascular cognitive impairment can start slowly and frequently subtle difficulties are not identified in early stages and can be misdiagnosed. After a certain vascular lesion load, the disease becomes progressive (as was the case with our patient), and even without any further vascular lesions, the clinical picture continues to deteriorate. In the past two decades, the concept has progressively evolved and new concepts such as “vascular cognitive impairment” [2–4] and “vascular cognitive disorder” [5,6] have been proposed to include the spectrum of cognitive and behavioral manifestations between mild and severe forms of cognitive involvement. The key aspect is, as in this case, that prevention of further strokes can prevent future damage and delay functional loss. Appropriate management of vascular risk factors, including antiplatelets and anticoagulants, was recently associated with improved protective effect on long-term cognitive outcome among stroke patients [7] in a population-based study. Considering isolated treatment, the best effect was noted after 10 years, using anticoagulants. However, the most impressive effect was from the use of optimal treatment, defined as concomitant treatment: antihypertensive, antiplatelets or anticoagulants, and lipid-lowering agents for ischemic strokes, and antihypertensive agents for hemorrhagic strokes [7].

There is no approved symptomatic treatment for vascular cognitive impairment [8] but there is some evidence of a small benefit using cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, probably related to the coexistence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology [9]. Use of these drugs must be cautious, as relevant side effects have been reported with cholinesterase inhibitors [9,10]. Moreover, in most countries, these drugs are not approved for this indication, thus, limiting their use.

Tip

Recurrent stroke is one of the most important risk factors for cognitive impairment after initial stroke. Even without clear memory complaints, professionals who manage stroke patients should be attentive to identify subtle cognitive difficulties (mainly in recurrent stroke patients) that frequently are mistakenly ascribed to depression. Prevention of further strokes is essential to prevent cognitive impairment.

Case 2. Cognitive impairment after strategic infarct

Case description

A 60-year-old civil engineer, running his own company at the time of admission, and a current smoker, was admitted to hospital with acute onset of somnolence and impaired vertical gaze. CT scan showed acute bilateral median thalamic infarcts (Figure 15.2).

Brain CT showing bilateral median thalamic infarcts.

He was hypertensive (unknown until then) and further ancillary evaluation was unremarkable. Initially, disturbed sleep–wake cycles and severe loss of initiative made neuropsychological testing quite difficult. In the following days, the somnolence and vertical gaze palsy improved. Neuropsychological evaluation showed a deficit in sustained attention, slowness, diminished verbal and motor initiative, and disturbed motor control. He also had a severe learning deficit for new facts, and episodic memory was severely impaired. Over the following months his attention and executive deficits improved, but memory was severely impaired with deficit in learning new information, even after repeated presentations of stimuli. Over the following years he continued to show improvement in his executive functions, but learning new facts did not return to normal levels and he was unable to return to work. The picture became stable, and no further deterioration was observed after 5 years of being followed as outpatient.

Discussion

This patient had an acute cognitive deficit, temporally related with the thalamic vascular lesions. The cognitive deficit was not related to the volume of tissue that was damaged, but instead was associated with the strategic location of the lesion [1]. Infarcts involving the paramedian territory of the thalamus can be bilateral due to involvement of the paramedian arteries, as these may arise from a single pedicle with a common origin, the Percheron artery, a single arterial trunk arising from the P1 segment of one of the posterior cerebral arteries. Paramedian thalamic arterial lesions cause the symptoms observed: decreased level of consciousness, vertical gaze palsy, and characteristic cognitive deficits. In the acute stage, loss of self-activation, abulia, and apathy are frequent. Difficulty in learning due to the lack of encoding of new information can be quite severe and persistent without improvement. Frequently, the infarct is due to a cardioembolic source, although no embolic source was identified in our patient. Cognitive rehabilitation can be useful in these patients; although it is usually described that the deficit in learning new facts remains without change, this patient learned how to adapt to daily-life routine. The patient continued to be stable after 5 years of evolution. There are no data to support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in strategic infarct dementia. Although data from animal studies suggest that memantine could improve motor control [11,12], further studies with better cognitive outcomes are needed.

Case 3. Challenging diagnosis of comorbidities in vascular cognitive impairment

Case description

A 76-year-old retired university teacher was admitted to hospital due to severe anorexia with weight loss of >10 kg over 3 months. He had hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He also had previous recurrent depressive episodes for more than 30 years, and was diagnosed with vascular cognitive impairment 2 years earlier. On admission, he was emaciated and dehydrated, with depressive mood. Whenever he tried to eat, he quickly gave up after attempting to ingest two or three spoonfuls, and refused to continue eating. Prior to his admission to the Dementia Unit, an ear, nose, and throat evaluation excluded structural changes. Electrodiagnostic studies excluded motor neuron involvement. Ancillary laboratory data demonstrated mild anemia and moderate renal insufficiency. No infectious or inflammatory changes were noted.

Discussion

Immediate approach and evolution

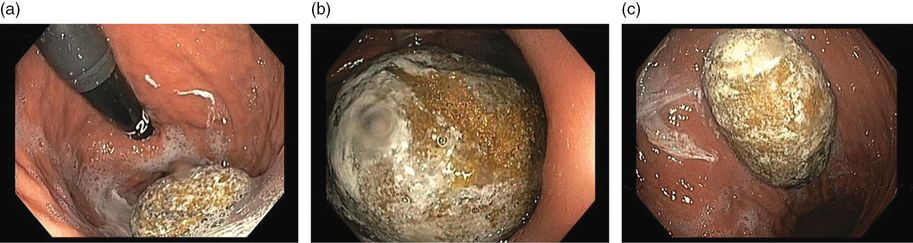

On admission we had three major hypotheses: (1) the dysphagia could be accounted for on the basis of cerebrovascular disease, or (2) his anorexia was due to worsening of depression, or (3) he could have a concomitant underlying disease accounting for his anorexia and weight loss. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, several changes in the neurologic examination can be found in patients with vascular cognitive impairment even in the initial stages, such as balance and gait abnormalities, dysphonia and dysphagia, paratonia, urinary incontinence, emotionalism with inappropriate crying and laughing, and presence of primitive reflexes. To further explore the hypothesis that our patient had one of the possible neurologic symptoms in the context of vascular dementia, a multidisciplinary approach was undertaken. Speech therapy and specialist nurse in swallowing evaluation excluded dysphagia as a cause of his inability to be fed, although the patient continued to refuse to eat. A psychiatrist adjusted the pharmacological treatment of his depression. His depression improved and was not considered severe enough to interfere with his ability to be fed. Investigations for associated comorbidities were conducted simultaneously, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a massive gastric bezoar (Figure 15.3). Attempts at endoscopic bezoar removal were not successful and open surgery was undertaken.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing massive gastric bezoar.

Discussion of the approach

This patient illustrates several important aspects in the setting of vascular cognitive impairment.

First of all, vascular cognitive impairment is a challenging disorder, as patients often have several comorbidities that potentially influence their health status. Unlike other degenerative dementias, patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases may have complex medical disorders and are often receiving several medications that could negatively impact on cognition. Adequate vascular risk factor control is of major importance, but frequently other comorbidities can also influence outcome.

Second, notwithstanding some symptoms can be part of the disease, cognitively impaired subjects deserve systematic investigations searching for treatable causes of deterioration, even if demented. A thorough assessment of comorbidities is recommended in cognitively impaired subjects, either during the initial encounter or throughout the course of the disease [13]. In our patient, a gastrointestinal pathology was the cause, but other diseases should be looked for and adequately approached.

Third, the best approach to a cognitively impaired patient should involve a multidisciplinary team. Although the effectiveness of multidisciplinary teams has not been studied in detail in vascular cognitive impairment, other examples already exist in the dementia field [14]. The objectives of a multidisciplinary team from a Dementia Unit include making an accurate diagnosis, staging the disease, and anticipating possible complications. The Dementia Unit team also aims to identify medical comorbidities and coordinate and monitor a plan of intervention. The team should include primary care/general physicians, nurses, and specialists in psychiatry, neurology, internal medicine, and rehabilitation medicine. The team should also count on nurses and nurse assistants, neuropsychologists and clinical psychologists, physical, occupational, and speech therapists and social workers.

Tip

Cognitive impairment and dementia should not preclude a thorough investigation and treatment of complications, unless a plan for palliative care has been predetermined. Decisions should be individualized, and optimal control of other complications should be the goal in cognitively impaired subjects.

Case 4. Challenging management in subcortical vascular cognitive impairment

Case description

A 75-year-old retired computer technician, married, living with his spouse was brought for neurology consultation due to multiple falls.

The patient had a previous history of a myocardial infarction 6 years earlier. He also had peripheral arterial disease (PAD), asymptomatic bilateral internal carotid stenosis (<50%), and an unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. His father and older brother had died from myocardial infarction. He had been diagnosed with vascular parkinsonism and was on selegiline 5 mg/day.

Of note, in recent years he had abandoned his usual hobbies and his interest in reading had decreased considerably. He had difficulties using the television remote control and video recording. His loss of initiative was disturbing to the family and he was also concerned about his own difficulties.

Neuropsychological evaluation showed a mild executive function deficit (namely in planning and organization), but no memory deficits. He was started on fluvoxamine 50 mg/day, 3 weeks before his first observation at the memory clinic. Since then, the patient had had several falls. In one of these falls he fractured his right hand. At the outpatient clinic, the patient appeared calm, with coherent speech, but was concerned about his multiple falls. On examination he had very mild bilateral hypertonia. He had no cogwheel rigidity. Muscle stretch reflexes were symmetrical. He had no tremor at rest. Cranial nerve function was unremarkable, including vertical gaze movements.

MMSE was 28 (two items lost due to orientation error: day of the month and day of the week). A previous brain CT showed moderate periventricular white matter changes and ventricular enlargement with widening of cortical sulci suggestive of cortical-subcortical atrophy. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed mild bradycardia (56/min). Carotid ultrasound and transcranial Doppler (TCD) were similar to previously obtained studies. A prolonged 12-lead ECG showed periods of severe bradyarrhythmia that were symptomatic (feeling dizzy), even in the lying position. He was admitted to the coronary care unit with continuous ECG monitoring, and selegiline and fluvoxamine were discontinued. The bradycardia slowly improved and no severe bradyarrhythmia episode was further identified. The patient had no recurrent syncope. However, he became confused and progressively agitated. Haloperidol was initiated, as he insisted on walking around the coronary care unit.

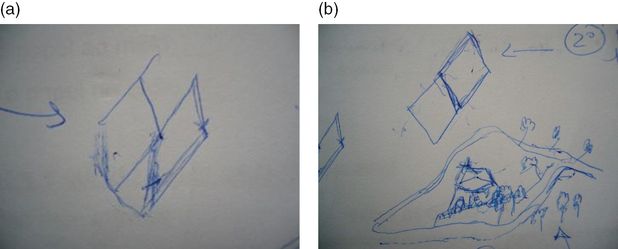

He returned home after 3 days in the coronary unit, and his confusional syndrome continued to worsen, with agitation and severe circadian sleep disruption despite the administration of neuroleptics in high dosages. He was then admitted to the Dementia Unit, with severe agitation and dehydration. On admission, he was agitated and had visual hallucinations and delusions. He drew his visual hallucinations while he was making the drawing of the MMSE (see first and second attempts – Figure 15.4a and b).

The patient’s drawing of MMSE figure at admission. The patient tried to copy twice. (a) First attempt; (b) second attempt, when he drew the visual hallucination.

Management and discussion

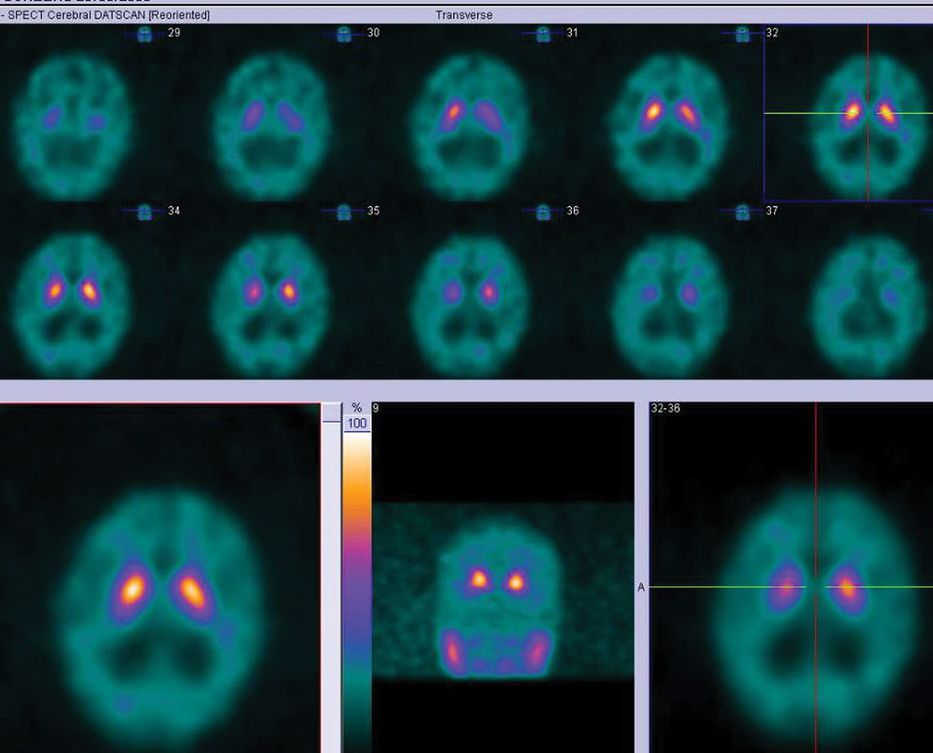

All pharmacological treatments were discontinued except for platelet antiaggregants. Over the first weeks he continued to deteriorate, and he became bedridden. The visual hallucinations increased and his circadian-sleep disruption became worse. Feeding the patient was challenging as he did not cooperate. At this point, we thought he had a different pathology, and proceeded with further investigations, trying to exclude: (1) rapidly progressive dementia due to the continuous and rapid deterioration and (2) Lewy body dementia due to the persistence of hallucinations and cognitive fluctuation. EEG showed diffuse slowing without other relevant changes, namely no periodic sharp-wave complexes or epileptic discharges. MRI (Figure 15.5) showed mild cortical and subcortical atrophy and hyperintensities compatible with small vessel disease on FLAIR imaging. No acute vascular lesions were noted on diffusion-weighted imaging. Due to the ventricular enlargement noticed on MRI (although there was no widening of the cortical sulci), a lumbar puncture was done with withdrawal of a large amount of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Opening pressure was normal and CSF biochemical, serological, and cultural tests were negative. The CSF protein 14-3-3 was negative. The dopamine transporter (DAT) SPECT scan showed no reduced tracer uptake (Figure 15.6).

MRI showing ventricular enlargement without widening of cortical sulci. No relevant changes in diffusion.

DAT-SPECT with normal tracer uptake.

At this point, we admitted that he could have a systemic process, as he had mild hypotension. A follow-up thoracic and aortic CT showed a stable unruptured aneurysm, similar to previous exam 2 years before, and no other relevant changes.

Meanwhile, the multidisciplinary team conducted daily interventions; the speech therapist and specialist nurse in swallowing worked together training swallowing; the physical and occupational therapists stimulated the patient. He also received subcutaneous hydration overnight, and 24-hour nursing care. Mild rigidity was present and levodopa was added in low dosage, after exclusion of other etiologies. No dopaminergic agonists were added. Slowly, after a month he became more cooperative, and feeding became possible. He started to cooperate with physical therapy and he was released after 2 months. A few months later, he had full independent gait but required help with some complex activities, but overall, he was independent in basic activities. He returned home with his wife, and follow-up re-evaluation 6 months later showed moderate deficits in executive functions (mental flexibility, motor and verbal initiative), and very mild memory deficit (immediate logical memory, recovering to normal level with cueing, no learning deficit). He remained stable in neuropsychological status 2 years and 4 years after and during his last evaluation in 2011 he had an MMSE of 25 (lost 4 points in temporal orientation, 1 in recall). He died in 2012 at the age of 80 years, due to sudden cardiac arrest.

This patient illustrates a prolonged delirium, which was probably caused by the association of drugs (selegiline – a selective MAO-B inhibitor – and fluvoxamine – a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) with consequent cardiac bradyarrhythmia in a patient with previous mild cognitive impairment of vascular etiology. Delirium is a frequent complication in patients with cognitive impairment, even among those who are slightly impaired. Delirium can reach a prevalence of 89% among hospitalized demented patients [15]. Persistence of delirium over weeks and months after an acute insult has been described, and some evidence suggests that patients with dementia and an increasing number of medical conditions have an increased risk of prolonged delirium [16]. There is suggestive evidence that delirium can partly represent a cholinergic deficit but there is no evidence that cholinesterase inhibitors can reduce the duration of delirium [17].

This patient also illustrates the subcortical type of vascular cognitive impairment [18,19]. Typically, subcortical vascular cognitive impairment is the expression of small vessel disease that is visible in brain imaging through white matter changes, lacunar infarcts, and microbleeds. The clinical picture is characterized by executive dysfunction, slowness and reduced processing speed, usually with some attention deficit, but memory can be preserved until later stages of the disease, so it can be underdiagnosed for years. There is some evidence that the cholinesterase inhibitor donepezil can improve executive function in a form of subcortical vascular dementia (CADASIL), but results must still be replicated [20]. The patient described also had signs that usually appear in cognitive vascular disorder, such as balance and gait abnormalities, usually more symmetrical with pyramidal signs, and less responsive to levodopa. Although vascular parkinsonism has been increasingly recognized, as yet, there are no accepted international criteria for its diagnosis [21].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree