Chapter 8 Vertigo

Physiologic Basis of Balance

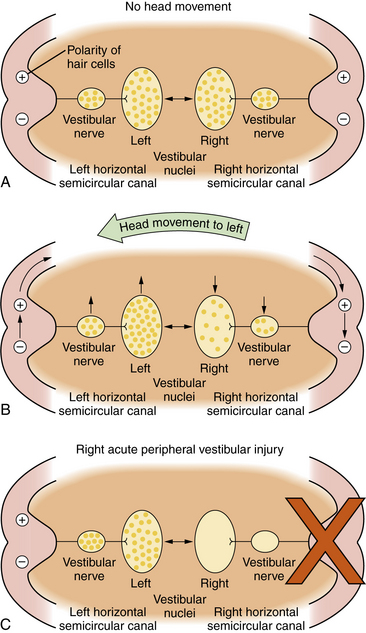

The oculovestibular reflex is a mechanism by which a head movement automatically results in an eye movement that is equal and opposite to the head movement so that the visual axis of the eye stays on target: that is, a leftward head movement is associated with a rightward eye movement and vice versa. Another feature of the oculovestibular reflex is that the two vestibular nuclear complexes on either side of the brainstem cooperate with one another in such a way that, for the horizontal system, when one nucleus is excited, the other is inhibited. The central nervous system responds to differences in neural activity between the two vestibular complexes. When there is no head movement, the neural activity, i.e., the resting discharge, is symmetrical in the two vestibular nuclei. The brain detects no differences in neural activity and concludes that the head is not moving (Figure 8-1A). When the head moves, e.g., to the left, endolymph flow produces an excitatory response in the labyrinth on the side toward which the head moves, e.g., on the left, and an inhibitory response on the opposite side, e.g., on the right. Thus, neural activity in the vestibular nerve and nuclei, e.g., on the left and right, increases and decreases, respectively (Figure 8-1B). The brain interprets this difference in neural activity between the two vestibular complexes as a head movement and generates appropriate oculovestibular and postural responses. This reciprocal push-pull balance between the two labyrinths is disrupted following labyrinthine injury.

An acute loss of peripheral vestibular function unilaterally, e.g., on the right, causes a loss of resting neural discharge activity in that vestibular nerve and the ipsilateral nucleus (Figure 8-1C). Since the brain responds to differences between the two labyrinths, this will be interpreted by the brain as a rapid head movement toward the healthy labyrinth, i.e. vertigo. “Corrective” eye movements are produced toward the opposite side, resulting in nystagmus, with the slow component moving toward the abnormal side, e.g., the right, and the quick components of nystagmus moving toward the healthy labyrinth, e.g., the left.

Evaluation of Patients with Dizziness

Physical Examination

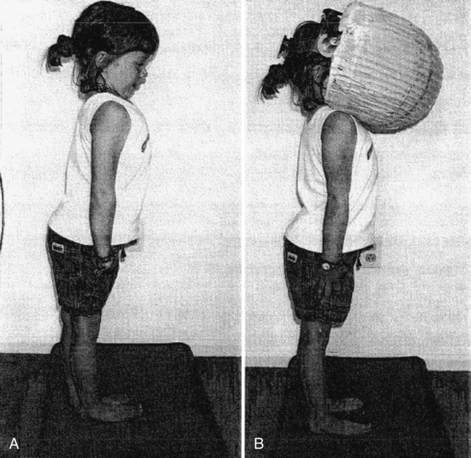

In addition to a complete neurologic examination, the child should also be observed when walking or running for incoordination of movements, i.e., ataxia. Also, an assessment of nystagmus is especially important. Spontaneous nystagmus is an involuntary, rhythmic movement of the eyes not induced by any external stimulation. Spontaneous nystagmus has two components: slow and fast. Nystagmus is named by the fast component, which is easily identified. Spontaneous nystagmus is tested by having the patient look straight ahead with and without fixation. Gaze-evoked nystagmus is assessed by having the patient deviate the eyes laterally (no greater than 30 degrees) with fixation. Positional testing is performed with the use of maneuvers that may produce nystagmus or vertigo. Static positional nystagmus is assessed by placing the patient in each of the following six positions: sitting, supine, supine with the head turned to the right, supine with the head turned to the left, and right and left lateral positions. Positional nystagmus presents as soon as the patient assumes the position and persists for as long as the patient remains in the provocative position. Assessment of vestibulospinal function with a foam pad (Figure 8-2) should be performed with or without a visual conflict dome.

Videonystagmography

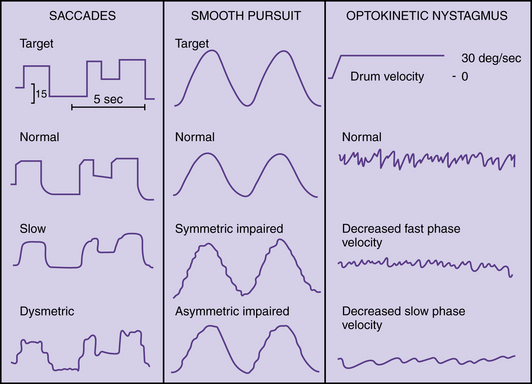

Videonystagmography (VNG) is currently the most widely used method of recording eye movements; it uses infrared light. Ocular motor testing, positional testing, and caloric testing constitute a common test battery that requires about 1 hour. Sedatives and vestibular suppressant medications should be discontinued for 2 days prior to testing. Ocular motor testing evaluates neural motor output independent of the vestibular system (Figure 8-3). Abnormalities in the ocular motor system may cause misleading conclusions from vestibular testing that relies on eye movements. Testing saccades uses a computer-controlled sequence of target jumps. Saccade abnormalities are defined as overshooting the target (hypermetric saccades) and undershooting the target (hypometric saccades). Disorders in the saccadic system suggest a central nervous system abnormality. Spontaneous nystagmus and gaze-evoked nystagmus are recorded with and without fixation (closing the eyes or darkness) (Figure 8-4), and by asking the patient to look 30 degrees to the right and left. Spontaneous nystagmus present in darkness without fixation, which decreases or resolves with visual fixation, suggests a peripheral vestibular disorder. However, spontaneous nystagmus that is present with fixation and does not significantly decrease with loss of fixation is most likely a central nervous system abnormality. Ocular pursuit involves asking the patient to follow a moving target back and forth along a slow pendular path. Normal subjects can follow a target smoothly without interruption. Abnormalities of pursuit tracking are caused by lesions in the central nervous system. Laboratory testing of optokinetic nystagmus uses black-and-white stripes moving left and right. Abnormalities include asymmetries or absence of responses, which suggest a central nervous system abnormality.

Fig. 8-4 Recording of spontaneous nystagmus.

(From Furman JM, Cass SP. Evaluation of dizzy patients. Slide lecture series. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Inc., Alexandria, VA 1994.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree