Meningococcal meningitis occurs in sporadic form and at irregular intervals in epidemics. Epidemics are especially likely to occur during large shifts in population, and crowding as in a time of war, and in college dormitories.

Pathobiology

Meningococci (N. meningitidis) may gain access to the meninges directly from the nasopharynx through the cribriform plate. The bacteria, however, are usually recovered from blood before meningitis commences, indicating that colonization of the nasopharynx with subsequent bacteremia and spread to the CNS is more common.

The bacterial polysaccharide capsule seems to be most important in attachment and penetration to gain access to the body. Elements in the bacterial cell wall (pili, fimbria) are critical for penetration into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the vascular endothelium and in induction of the inflammatory response.

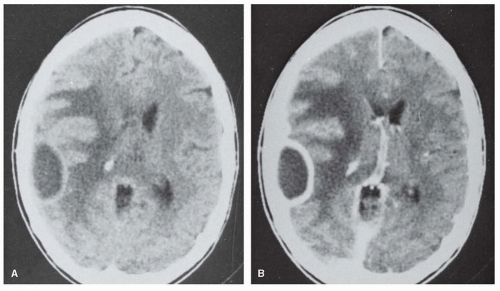

In acute fulminating cases, death may occur before there are any significant pathologic changes in the nervous system. In the usual case, when death does not occur for several days after onset of the disease, an intense inflammatory reaction occurs in the meninges. The inflammatory reaction is especially severe in the subarachnoid space over the convexity of the brain and around the cisterns at the base of the brain. It may extend along the Virchow-Robin perivascular spaces into the brain and spinal cord. Meningococci, both intra- and extracellular, are found in the meninges and CSF. With progression of the infection, the pia-arachnoid becomes thickened and adhesions may form. Inflammatory reaction and fibrosis of the meninges along the roots of the cranial nerves are thought to cause the cranial nerve palsies that are seen occasionally.

Damage to the auditory nerve often occurs suddenly, and the resulting hearing loss is usually permanent. The damage may result from extension of the infection to the inner ear or from thrombosis of the nutrient artery. Signs and symptoms of parenchymal damage (e.g., hemiplegia, aphasia, and cerebellar signs) are caused by infarcts resulting from thrombosis of inflamed arteries or veins.

In the past, the inflammation in meningitis had been attributed mainly to the toxic effects of bacteria. In all types of meningitis, the contribution to the inflammatory process of cytokines released by phagocytic and immunoactive cells, particularly interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor, has been recognized. These studies have formed the basis for the use of anti-inflammatory corticosteroids in the treatment of meningitis.

Clinical Manifestations

The onset of meningococcal meningitis is similar to that of other forms of meningitis and is accompanied by chills and fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, pain in the back, stiffness of the neck, and prostration. The occurrence of a petechial or hemorrhagic skin rash is a manifestation of meningococcemia. At the onset of meningitis, the patient is irritable. In children, there is frequently a characteristic sharp, shrill cry (meningeal cry). With progress of the disease, the sensorium becomes clouded and stupor or coma may develop. Occasionally, the onset may be fulminant and accompanied by deep coma. Convulsive seizures are often an early symptom, especially in children, but focal neurologic signs are uncommon in the initial presentation.

The patient appears acutely ill and may be confused, stuporous, or obtunded. The temperature is elevated at 101°F to 103°F, but it may occasionally be normal at the onset. The pulse is usually rapid and the respiratory rate is increased. Blood pressure is normal except in acute fulminating cases when there may be profound hypotension. A petechial rash may be found in the skin, mucous membranes, or conjunctiva in meningococcemia but never in the nail beds. It usually fades in 3 or 4 days. There is rigidity of the neck with Kernig and Brudzinski signs. These signs may be absent in newborn, elderly, or comatose patients. Increased intracranial pressure causes bulging of an unclosed anterior fontanelle and periodic respiration. Cranial nerve palsies and focal neurologic signs are uncommon and usually do not develop until several days after the onset of infection. The optic discs are normal, but papilledema is a sign of increased intracranial pressure.

Complications and sequelae include those commonly associated with any inflammatory process in the meninges and cerebral blood vessels (i.e., convulsions, cranial nerve palsies, focal cerebral lesions, damage to the spinal cord or nerve roots, hydrocephalus) and those that are due to involvement of other portions of the body by meningococci (e.g., panophthalmitis and other types of ocular infection, arthritis, purpura, pericarditis, endocarditis, myocarditis, pleurisy, orchitis, epididymitis, albuminuria or hematuria, adrenal hemorrhage). Disseminated intravascular coagulation may complicate the meningitis. Complications may also arise from intercurrent infection of the upper respiratory tract, middle ear, and lungs. Any of these complications may leave permanent residua, but the most common sequelae are due to injury of the nervous system. These include deafness, ocular palsies, blindness, changes in cognitive functioning, convulsions, and hydrocephalus. With the available methods of treatment, complications and sequelae of meningeal infection are rare, and the complications due to the involvement of other parts of the body by the meningococci or other intercurrent infections are more readily controlled.