46

Anterior Lumbar Surgical Exposure Techniques

Rick B. Delamarter, Salvador A. Brau, and Ben B. Pradhan

Description

Anterior approaches have been developed for easier and more direct access to the anterior and middle columns of the lumbar spine. Easier access for the spine surgeon implies that a more thorough and complete diskectomy or corpectomy can be performed with increased efficiency. Today this often involves collaboration with a vascular-trained access surgeon. Depending on the circumstance, a left-sided or right-sided (for L5-S1 only) retroperitoneal approach, can be performed. A direct transperitoneal (transabdominal) approach is usually reserved for revision cases.

Key Principles

The location, orientation, and size of the incision and the approach can vary according to the location and extent of the pathology, the size of the patient, prior anterior abdominopelvic surgeries, the nature of the spinal procedure to be performed, and the experience of the access surgeon (Fig. 46.1).

Fig. 46.1 Exposure of the L5-S1 disk.

Expectations

The expectation is not only that the area of pathology be well visualized, but also that all the abdominal and pelvic structures be safely retracted, and that they remain well retracted during the extent of the surgical procedure (Fig. 46.2). Furthermore, it is desirable that adequate lighting be available because the overhead lights are often blocked by the surgeon during the procedure; adequate lighting can be provided by selfilluminating retractors or by head lights. With some of the modern interbody or corpectomy devices, and artificial disk replacements, it is also necessary for the surgical segment(s) to be visualized radiographically with the retractors in place, which is made possible by radiolucent retractors.

Fig. 46.2 One-level exposure with disk midline marked (for prosthetic disk placement).

Indications

Any procedure involving anterior lumbar interbody fusion or anterior lumbar corpectomy and fusion, which are usually performed for intractably symptomatic degenerative disk disease, deformity, instability, trauma, tumor, or infection.

Contraindications

An active abdominal or pelvic infection is a contraindication to anterior lumbar surgery in the same vicinity, unless the target of the surgery is an infection in the spine itself. Relative contraindications include previous anterior surgery at the operative level, morbid obesity, severe atherosclerosis of the anterior blood vessels, and severe endometriosis or other pelvic inflammatory disorders.

Special Considerations

Because the exposure is only as good as how well it can be maintained, having a good retractor system is key. We favor a table-held retractor system, because it keeps a steady pressure (as determined to be safe by the access surgeon) on the abdominal contents, minimizes readjustments of the retractors on the tissues, and frees up the hands for performing the procedure. Our experience is that the anterior lumbar surgery (ALS) radiolucent retractor blades with reverse lips at the tips (Thompson Surgical Instruments, Inc., Traverse City, MI) stay anchored onto the sides (anterolateral gutters) of the lumbar spine very well, minimizing slipping and springing out. These retractors come with adaptable handles for use with any of the existing table-held retractor systems currently available. These retractors come in both rigid and malleable versions and are strong enough to hold back the tissues once deployed. This is especially helpful during artificial disk replacement surgery, where a wider anterior exposure of the disk is necessary to identify the midline of the disk, perform a thorough diskectomy, restore disk height symmetrically, and elevate a contracted posterior longitudinal ligament if necessary (Fig. 46.3).

Fig. 46.3 Final view with prosthetic disk in position.

We caution against the use of Hohman retractors and Steinmann pins drilled into the vertebral bodies for retraction, as they may structurally damage the vertebra if knocked loose, and by virtue of their sharp tips can damage nearby tissues during placement or removal.

It is generally a good idea to have cell saver machinery set up during the surgery, as bleeding can be brisk from a vascular laceration in this area, although this is fortunately a rare occurrence with experienced access surgeons. Rarely, a clot can form or an atherosclerotic plaque may break off inside a vessel at the retracted site, which may require additional vascular surgery, and the cell saver will be necessary.

A pulse oximetry setup on the patient’s left big or second toe can provide valuable information about blood flow and pulses across the vessels in the operative area. A warning tone tells the access surgeon when blood flow to the extremity is compromised, and thus the amount of ischemia time can be monitored. If the procedure causes ischemia for 45 to 50 minutes, the pressure on the vessels can be released for 30 seconds and the retractors reapplied for another 30 minutes. Pulse oximetry can also be invaluable in assessing pulse and blood flow at the end of the procedure. If the saturation does not return to pre operative levels, left iliac artery thrombosis is diagnosed unless proven otherwise. In our experience, cases of arterial thrombosis have been detected with the help of this technique.

Antiemetics, such as Reglan, and gastric decompression are recommended during the procedure. Nasogastric or orogastric tubes may be inserted after the patient is under anesthesia and removed at the completion of the procedure. They help reduce the incidence of ileus.

Special Instructions, Position, and Anesthesia

It is good practice to examine the preoperative radiographs to assess the location of the surgical level against palpable landmarks such as the iliac crests or pubis. Inspection of the lateral radiograph also reveals whether the bottom disk spaces are easily accessible with a good line-of-sight over the pubis, and where the incision should be made for ideal visualization of the angled disk spaces.

The exact procedure planned and the type of instrumentation to be performed should be relayed to the access surgeon (e.g., fusion versus artificial disk replacement), because the optimal type, extent, and orientation of the approach may vary. For example, for an artificial disk replacement, a symmetric anterior exposure of the disk space is needed to properly center the device, whereas for a fusion, a limited anterolateral exposure may be sufficient.

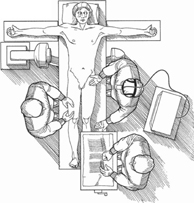

The patient is positioned supine on a radiolucent (e.g., Jackson) table that will accommodate a fluoroscopy machine positioned under and across it for anteroposterior and lateral image intensification. If a regular operating table is used, it may have to be reversed head-to-toe to make this possible. The arms should be abducted at approximately right angles to the body to allow plenty of room for fluoroscopy machine positioning. Although not used at our center, a Trendelenburg position is reported to be helpful sometimes as it allows the abdominal structures to move in a cephalad direction.

A small bump may be placed under the back to lordose the spine for access into the disk space. However, too large a bump can cause the anterior vessels to drape against the anterior of the spine, making them difficult to mobilize. An inflatable pneumatic bladder and pump make it easy to adjust the lordosis intraoperatively.

Anesthesia should provide complete muscle relaxation throughout the procedure because the retractors are under tension, and loss of relaxation can cause them to become dislodged.

Tips, Pearls, and Lessons Learned

At times, optimal retraction cannot be maintained by self-retaining retractors, and a hand-held malleable retractor may need to be held in place by an assistant. The surgeon must always keep an eye out for tissues, such as vessels or the ureter, that may be exposed or may protrude between the retractor blades. We recommend holding an instrument (e.g., suction tip or surgical sponge) in the nondominant hand to protect tissues from the working field where the dominant hand is performing the diskectomy. If the protrusion is large or increasing, or if the retractors are unstable, it is better to adjust them early or to call this to the attention of the access surgeon sooner than later. If a burr or drill has to be used, it should be turned on only after the working end (bit) is totally inside the disk space, and should be turned off and the bit should be still before removing it from the disk space.

Retrograde ejaculation is a possible complication with this approach in males, with a reported incidence ranging from less than 2 to 10%. This is a risk that must be discussed with patients, especially if they are planning on fathering children in the future. If so, some may choose to exercise the option of donating sperm to a sperm bank.

Cautery around the anterior spine should be minimized. It has been reported that the incidence of retrograde ejaculation in males may be higher with the use of cautery in this area (bipolar cautery is probably safer, with less electrical arcing). To reduce retrograde ejaculation, elevate the peritoneum away from the promontory with a Kittner. The fibers of the superior hypogastric plexus run adherent to the peritoneum, much as the ureter does. Mobilize this peritoneum to the right, if working from the left at L5-S1, and then the fibers will be protected once the retractor is deployed on the right side of the spine. Other means of maintaining hemostasis (e.g., ties, clips, Gelfoam, thrombin, other hemostatic agents), and blunt dissection (peanuts, laps) are also recommended.

Oval-shaped, sturdy suction tips may be useful to enter narrow disk spaces, and can also be used to lever open tight disk spaces during diskectomy.

Specially designed disk space distractors can be used to sequentially distract the disk space, making it easier to progress along with the diskectomy with good visualization. Distractors also allow visualization of the posterior vertebral edges, which is necessary for complete diskectomy and if posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) elevation is needed. We prefer the ProDisc-L distractor (Synthes Spine, Paoli, PA) because it can be confined in one half of the disk space while the surgeon works in the other half, and then can be switched to the other side once the first half is finished. It is key, however, not to distract the distractor with its tips in the central weaker part of the end plate, as this may cause fractures and increase the risk of subsidence of the interbody device (which is especially undesirable for an artificial disk). The distractor tips should reach across to the posterior apophyseal ring before expansion (fluoroscopy may be needed to ensure this).

It may be advisable to instrument the tightest disk level first if operating on multiple levels; otherwise the surgeon may find it difficult to get a decent-sized device in after the other levels have been instrumented. Sometimes it may even be necessary to perform diskectomies at the other levels, and then to begin instrumentation at the tightest disk space. However, one has to minimize the number of times the retractors have to be moved. One solution would be to perform diskectomies from the taller disk to the tightest one, and then instrument from the tightest disk to the taller one.

Difficulties Encountered

The greatest difficulty is encountered during mobilization of the great vessels, especially at the L4-L5 level, where over 90% of all vascular injuries have been shown to occur. At the L5-S1 level, this is not as serious a problem because it is usually below the bifurcation of the vessels.

Scarring produced by a previous surgery or inflammatory process can certainly increase the difficulty of the dissection. Meticulous attention must be paid to identifying all the important anterior structures such as the bowel, vessels, and ureters. Stents may be placed in the ureters by an urologist prior to the surgery to aid in identifying and protecting them. The stents can be removed after surgery.

Key Procedural Steps

The patient should be positioned as mentioned above (Fig. 46.4). If autologous iliac crest bone graft is to be harvested, this can be done during the approach, but prior to deployment of the table-held, self-retaining retractors. Additional risk is possible if the retractors are removed for graft harvest, and then placed in again.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree