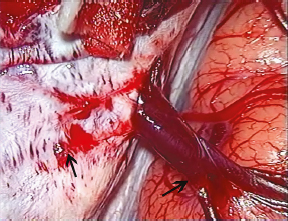

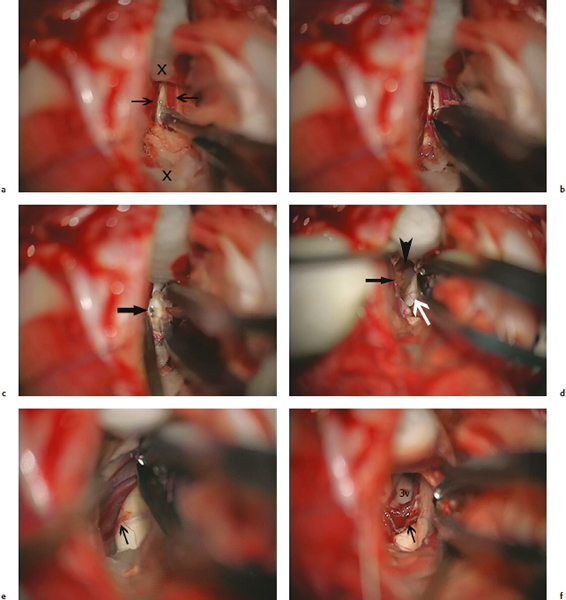

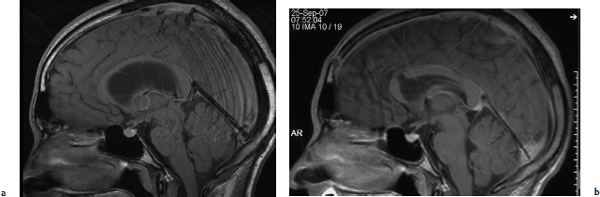

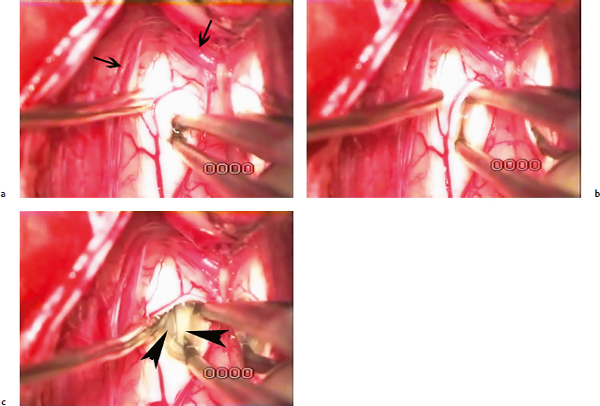

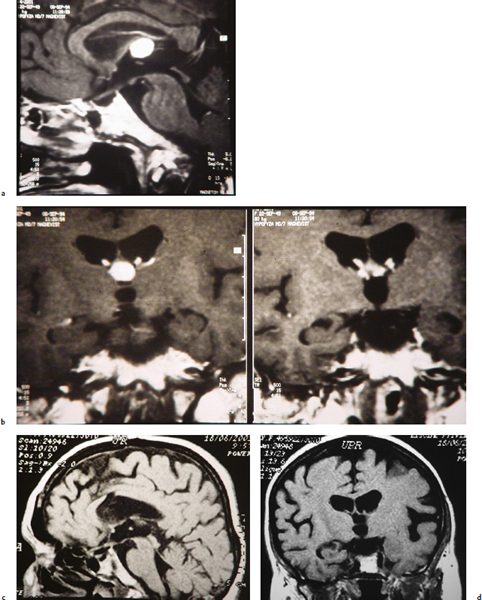

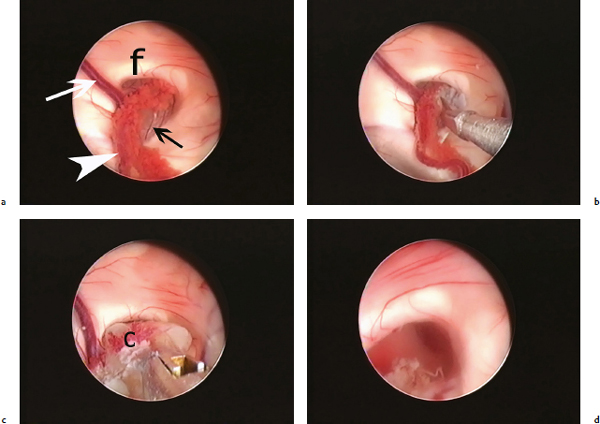

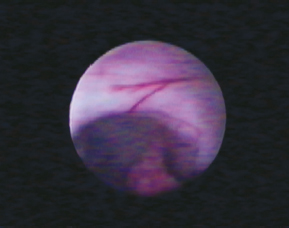

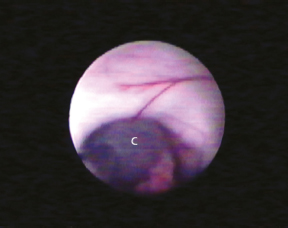

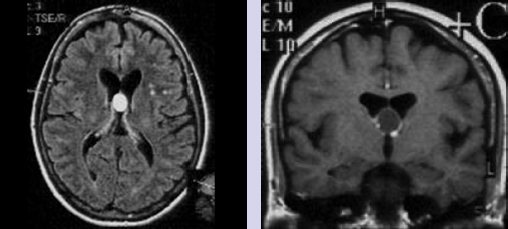

Chapter 12 Case A 35-year-old man notes an ongoing headache and visual blurring. Participants The Cranial Approach for Resecting Colloid Cysts: Juraj Šteňo Endoscopic Resection of Third Ventricular Colloid Cysts: Jalal Najjar, Emad T. Aboud, and Samer K. Elbabaa Moderators: Approaches to Colloid Cysts: Endoscopic vs. Microsurgical Treatment: Engelbert Knosp and Aygül Mert The patient described in this case has symptoms of rather severely increased intracranial pressure. According to the T1-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), his lateral ventricles are enlarged because of obstruction of the foramina of Monro by a cystic lesion located in the anterior–superior part of the third ventricle. This lesion is apparently a colloid cyst, and the condition is life threatening. Observation only is very dangerous; without surgical treatment, the patient is endangered by the decompensation of intracranial hypertension with a sudden loss of consciousness and even death.1 Two of 25 patients in our surgical series of colloid cysts were admitted to the hospital in a coma, necessitating emergency external ventricular drainage before the cyst was excised. The chosen treatment should remove the obstruction of the cerebrospinal fluid pathways as well as relieve compression of the fornix by a tense cyst. The procedure should reach these goals as safely as possible and aim to prevent recurrence. Colloid cysts are located inside the third ventricular cavity, most often in its anterior-superior compartment; the upper anterior part of the cyst is exposed at the foramina of Monro. A more posterior location of the cyst under the roof of the ventricle is rare. The orientation of the plane of the foramen of Monro, represented by its circumference, is oblique, tilting laterally and anteriorly. Its medial and posterior parts are located higher than the lateral and anterior borders. Consequently, the more lateral and anterior the point of entry at the surface of the brain, the more perpendicular and thus more suitable is the trajectory to the foramen of Monro. Therefore, the angle under which the foramen of Monro is exposed is more convenient with the transfrontal transventricular approach as compared with the transcallosal approach. The fornix, the choroid plexus, and the veins of the venous angle are often displaced in a manner that leads to enlargement of the foramen. However, the foramen may also be narrowed or, rarely, practically occluded so the cyst wall cannot be seen from the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle. The distortion of the anatomic structures and the resultant shape of the foramina of Monro are usually asymmetrical, and preoperative MRI often cannot show the exact size of the foramina. The access to both foramina of Monro, and thus the possibility of choosing the one that can better expose the cyst, is a great advantage of the transcallosal approach. Obstruction of the cyst by the choroid plexus is easily solved through coagulation and dissection. More problematic is the covering of the upper part of the cyst by both halves of the fornix, which is distorted over the surface of the cyst. In one of our patients, the cyst was completely covered by the flattened halves of the fornix and the leaves of the septum. In such cases, the most convenient approach from the technical point of view is a midline dissection of the fornix. In about a third of anatomic specimens, the venous angle is located posterior to the foramen of Monro; if necessary, the foramen may be enlarged through dissection of the choroid plexus on the forniceal side.2 The surgeon can choose among four methods of treatment for patients with a colloid cyst: stereotactic aspiration3; endoscopy (through a working channel,4,5 with the dual-port technique,6 or through a neuro-endoport7); endoscope- assisted microsurgery through a craniotomy8; and microsurgery.9–15 In the past, stereotactic aspiration was done without any visual control; later, a ventriculoscope was introduced to allow a view of the foramen of Monro and the capsule of the cyst.16 Endoscopy offers non-stereoscopic monocular vision and one-handed manipulation; a wider tubular port (neuro-endoport) and the dual-port technique enable a bimanual surgical technique. Microsurgery and endoscope-assisted microsurgery through a craniotomy enable bimanual surgical manipulation under stereoscopic vision. The disadvantage of monocular vision can be overcome through adequate experience with the endoscope. A more important drawback is the surgical manipulation with only one hand. The support and proprioceptive information provided by the second hand is invaluable during dissection of the structures, and is indispensable when structures must be pulled apart to stretch adhesions between them before cutting. Radical excision of the colloid cyst with microsurgical procedures can be achieved in all or almost all patients,8,12,17–20 whereas remnants of the cyst after endoscopic procedures are found in a range of 4% of patients up to the majority of patients.4,5,17,20,21 As might be expected, the recurrence rate after endoscopy is higher than after microsurgical resection. All surgical approaches to the third ventricle necessitate incision of the neural tissue, except for the supracerebellar subtentorial approach,1,22 which is more convenient for reaching the posterior part of the third ventricular chamber. A consequence of surgical transgression of the cerebral cortex is the development of seizures; after transcortical approaches to the tumors of the third ventricle, they occur in 8.6 to 28% of patients.23–25 After the transcallosal approach, they are rare.12 An opposite proportion was found in a single series of patients with tumors in and around the lateral and third ventricles, in which the transcallosal approach carried a 4.4-fold increased risk of seizures.26 The experience described in series of patients with colloid cysts is the same as in the majority of reports of all patients with third ventricle tumors. Antunes and colleagues27 reported seizures in two of 23 patients after the transcortical approach and in none of eight after callosotomy. Pamir and associates12 noted seizures in one of 19 patients after the transcallosal excision of colloid cysts complicated by subsequent venous infarction of the superior frontal gyrus. We used the transcallosal approach in 45 of 141 patients with tumors of the third ventricle and transcortical approaches in 11 of these patients (10 transfrontal, one posterior after Van Wagenen). Epileptic seizures occurred in one patient treated with the transcallosal approach (2.2%) and in two patients treated with the transcortical approach (18%), and all three of these patients harbored gliomas.28 Seizures did not occur in any of our patients with colloid cysts. From the neuropsychological point of view, the anterior transcallosal route is a safe and feasible alternative to the transcortical approach.29 The interhemispheric transfer of information is preserved as long as the splenium remains intact.30 Partial sectioning of the corpus callosum does not cause significant neurologic deficits; however, if the surgery induces additional brain injury, the neurologic deficits can be more severe with a callosotomy.31 We used the transfrontal-transventricular approach in three patients—in two after conversion from endoscopy to a craniotomy and in one to avoid the transection of a bridging vein. Likewise, the great majority of authors prefer the transcallosal approach, and we used it in 18 patients. Currently, we dissect the bridging veins from the dura even if the terminal part of the vessel runs between the dural layers (Fig. 12.1) or we open the dura atypically to reach the edge of the superior sagittal sinus. A sufficient callosotomy and complete removal of the cyst was possible when the anterior-posterior distance between the bridging veins at the sinus was as little as 20 mm. For the transcallosal approach, we adjust the placement of the craniotomy to the anatomy of the veins of the frontal lobe as shown by MRI. We use neuronavigation to find the most suitable trajectory from the convexity of the brain (as anterior as possible) via the corpus callosum (just behind the genu) to the foramina of Monro. The posterior border of the craniotomy rarely exceeds the coronal suture; it extends 1.5 cm across the midline medially. After opening the dura with the base of the flap at the superior sagittal sinus, we proceed along the falx, separating the medial surface of the frontal lobe in the direction of the foramen of Monro. On the way down to the corpus callosum, fine adhesions are dissected between the medial surfaces of the frontal lobes and between the anterior cerebral arteries and the surrounding structures. Gradual evacuation of the cerebrospinal fluid while working with the suction in one hand and forceps in the other relaxes the brain sufficiently to prevent its compression by a retractor. Currently, we seldom use retractors during dissection. In a rare case, when the brain was too tight even after the patient’s head was elevated, we punctured the frontal horn of the lateral ventricle and inserted a silicon tube, which we left in place until the end of tumor resection. Once the corpus callosum is exposed, rolled cottonoids are introduced between the cingulate gyri in front of and behind the planned incision (Fig. 12.2). The callosotomy is made in the midline to prevent damage to the indusium griseum, as recommended by Winkler and colleagues.32 We try to find an avascular zone but, rarely, a minute vessel has to be coagulated and transected. After sectioning the pia mater and some 1 to 2 mm of surface tissue approximately 8 to 10 mm long, we carry out blunt dissection by opening the arms of the forceps in the sagittal direction (Fig. 12.3). A dditional cuts are made if necessitated by the location of the foramen of Monro. In patients with severe hydrocephalus and a thinned-out corpus callosum, a mere puncture with the tip of a fine forceps is sufficient to reach the frontal horn of one of the lateral ventricles or the space between the leaves of the septum pellucidum (Fig. 12.4). We fenestrate the septum in all patients to inspect both foramina of Monro and to choose the one that allows better exposure, similar to the strategy used by Yaşargil and Abdulrauf.14 We use the other foramen just to assess the completeness of cyst excision. Fig. 12.1 The bridging vein draining the frontal lobe is dissected free from its attachment to the dura (arrows) up to its entry into the superior sagittal sinus. Dissection of the cyst usually starts with coagulation of the attached choroid plexus and with its dissection from the cyst wall. Opening the cyst and emptying its contents relieves tension and allows dissection of the capsule from the lower surface of the fornix and from the veins contributing to the venous angle. However small the foramen at the beginning, during dissection of the capsule from surrounding structures it always enlarges. Dissection of the choroid plexus in a posterior direction either from the forniceal or ventricular side (the subchoroidal approach15) further widens the exposure of the cyst. In cases with an atypical posterior variant of the venous angle, dissection of the plexus allows substantial enlargement of the approach.2 In one of our patients, this maneuver allowed the safe removal of a cyst located posteriorly between the roof of the ventricle and the massa intermedia (adhesio interthalamica) (Fig. 12.5). In one case, a minute vein of the septum pierced and apparently drained the fornix; on its way laterally to the venous angle, it firmly adhered to the surface of the cysts and its dissection and preservation required lengthy and meticulous technique (Fig. 12.2e). After complete removal of the cyst, the lateral walls and the floor of the third ventricle come into view. Fig. 12.4a–c (a,b) The callosotomy is done through puncture of the thinned corpus callosum between the pericallosal arteries (arrows) with the forceps. (c) The leaves of the septum pellucidum (arrowheads) are spread apart. In three patients with both foramina of Monro no more than a slit, we used the interforniceal approach.9 The body of the fornix was dissected at its midline raphe within the corridor bounded by the anterior commissure anteriorly and the choroid plexus at the foramen of Monro posteriorly. The anatomic situation, with the leaves of the septum being apart, helps the surgeon determine the precise orientation. After separation of the two halves of the fornix, the upper part of the cyst is exposed. Attachments to the lower surface of the fornix, the choroid plexus, and the veins are then dissected free and the cyst is removed. In a series of patients with cysts removed through the interforniceal approach, no permanent deficit was reported.33 We observed temporary memory disturbances in two of our three patients. The disturbance was rather severe in one of them, and afterward we did not use this approach. We achieved radical cyst resection in 21 patients treated microsurgically (including two patients after conversion of endoscopy to microsurgery because of venous bleeding) and in one of four with an accomplished endoscopic procedure (Fig. 12.6). There was no permanent morbidity or mortality in the entire series. Temporary memory disturbances occurred in four patients—in two after resection of the cyst through the transcallosal transforaminal route and in two of three after the interforniceal approach. Meningitis occurred in one of two patients with external ventricular drainage, and repeated shunt revisions were necessary. Preserving all bridging veins draining the frontal lobe prevents venous infarction. Dissection of the terminal parts of these veins from the dura or modified dural opening prevents their occlusion. Surgical manipulation of the fornix should be as gentle as possible. Bilateral manipulation especially may lead to the temporary impairment of short-term memory. Therefore, it is advisable to remove the tumor through one foramen of Monro and to use the other just to assess the completeness of resection, if necessary. The transforaminal exposure and resection of the cyst is preferable to the interforniceal approach. Traction on the veins contributing to the venous angle should be avoided as it may cause bleeding remote from the foramen of Monro. A two-handed operative technique increases the safety of tumor dissection. Fig. 12.6a–d Endoscopic removal of a colloid cyst through the right foramen of Monro. (a) At the foramen (f), the cyst (black arrow) is covered by the choroid plexus (arrowhead) and the anterior septal vein (white arrow) is beneath it. (b) Cutting the choroid plexus. (c) Removing the thick cyst contents. (d) The floor of the third ventricle seen through the emptied foramen of Monro. Closure of a callosotomy with fibrin glue is sometimes recommended. We always try to fill the intradural space with saline before the final dural stitch is taken to prevent collapse of the hemispheres and eventual bleeding from the stretched bridging veins. Colloid cysts derive their name from the Greek word kollodes (glue). They were first described as lesions within the third ventricle, but also appear in the fourth ventricle34 and within the brain parenchyma.35 There has even been one case of an olfactory groove colloid cyst that presented with cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea after eroding the dura of the anterior cranial fossa.36 Colloid cysts are benign, congenital epithelium-lined cysts that almost always arise in the anterior third ventricle. These rare tumors comprise 0.5 to 1% of all intracranial tumors and 15% of all intraventricular tumors. Colloid cysts are considered a potential cause of sudden death and acute neurologic deterioration,37,38 which occurs in one third of symptomatic patients. Among all cases of sudden death, 10 to 15% had a colloid cyst at autopsy.37 Both brain herniation and spinal infarction as a result of acute hydrocephalus have been described,39 and neurogenic pulmonary edema has also been mentioned as the mechanism triggering sudden death.40 On rare occasions, a colloid cyst may spontaneously resolve or rupture asymptomatically.41 Different surgical approaches have been described for resecting colloid cysts. The goal of any planned surgery is to achieve gross total resection with no residual capsule. Serial follow-up MRI studies are used to rule out any recurrence. The choice of any surgical approach should be geared toward avoiding complications and minimizing the manipulation of brain tissue and vasculature. Postoperative complications may include seizures, disconnection syndrome, memory difficulties, meningitis, and venous infarction. A review of most published articles would indicate that the microsurgical resection of colloid cysts leads to better gross total removal than the endoscopic approach. On the other hand, endoscopic resections create fewer complications in general. The endoscopic approach is becoming more effective and well accepted as gross total resection is achieved with a low risk of complications. In 1921, Dandy accomplished the first successful resection of a colloid cyst through a transcortical approach, and the transcallosal approach was first described by Green-wood in 1948. In the past 20 years, endoscopic approaches have become more popular. Other approaches include stereotactic aspiration and the infratentorial supracerebellar approach.22 Colloid cysts enlarge through an increased secretion of mucinous fluid from the lining of the epithelial cell wall. In addition, cyst cavities may be filled with blood and degradation products such as cholesterol crystals. Different theories exist concerning the origin of these lesions, which may include primitive neuroepithelium, ependyma, choroid plexus epithelium, and paraphysial tissue. But there is no structural or immunohistochemical evidence to support an ependymal or choroid plexus origin.42 Some studies conclude that colloid cysts of the anterior third ventricle are clearly distinct from both the choroid plexus and ependyma, and therefore are not a developmental or degenerative product of these structures.43 Tsuchida and colleagues44 suggested a nonneuroepithelial origin of colloid cyst epithelium, underscoring its similarity to respiratory mucosa of the trachea and sphenoid sinus. Surgical approaches to lesions located in the anterior and middle portions of the third ventricle are challenging, even for experienced neurosurgeons. Various approaches through the foramen of Monro, the choroidal fissure, the fornices, the lamina terminalis, and, rarely, the supracerebellar infratentorial route have been described in numerous publications.2 Wallmann first reported the case of a colloid cyst in 1858 in a man with urinary incontinence and ataxia.45 In 1921, Walter Dandy accomplished the first successful resection of a colloid cyst through a transcortical approach. He described a transcortical-transventricular approach to the third ventricle as partially resecting the frontal lobe to remove a colloid cyst. In 1949, James Greenwood46 reviewed 60 colloid cyst cases, in which 15 were successfully removed. He concluded that surgical removal must be accomplished without damage to the walls of the third ventricle, as the attachments of the colloid cyst to the wall of the third ventricle are fragile. He described the cyst’s movement as a ball valve at the level of the foramen of Monro, suggesting that the surgical approaches should be either transcortical or through the corpus callosum. His report described the importance of delivering the cyst only after removing the adjacent choroid plexus (Fig. 12.7). Fig. 12.7 Endoscopic view of a colloid cyst at the roof of the third ventricle with its choroid attachment at the right foramen of Monro. Early reports of the transcortical approach recommended its use in patients with hydrocephalus, and the common complications included the increased risk of seizures as well as infections. The transcallosal approach is commonly used to gain access to the third ventricle, but also has some disadvantages. Complications include direct or manipulation injury of the superior sagittal sinus and bridging veins, sometimes leading to sinus thrombosis and venous stroke. Some authors advocate the use of a large bone flap to avoid direct retraction of the sinus; others suggest the use of preoperative magnetic resonance venography for optimal evaluation of the venous anatomy and surgical planning.47 Other complications include bleeding or spasm of the pericallosal arteries because of manipulation or chemical irritation from the contents of the cyst.48 Forniceal injury can cause severe short-term memory loss and disconnection syndrome.49 Ulm and colleagues50 have detailed the limitations of the transcallosal transchoroidal approach to the third ventricle. They concluded that the exposure of the anterior third ventricle was limited by the columns of the fornix and by the presence of parietal cortical draining veins. Colloid cysts have been described as a pendulous pathology in the third ventricle. This theory correlates with the symptoms of patients, which are likely caused by intermittent obstruction of the foramen of Monro and include paroxysmal headaches that last from seconds to minutes and are initiated, exacerbated, or relieved by a change in the position of the head.51 The pendulous theory also explains the spontaneous collapsing and floating of the cyst capsule by pulsations in cerebrospinal fluid after surgical aspiration of the cyst’s contents. The cyst wall has no attachments except at its origin. Commonly, there is a firm attachment to the adjacent choroid plexus. Using a microsurgical technique, most neurosurgeons deliver the cyst from the third ventricle into the lateral ventricle and follow with careful coagulation and cutting of the attachment to the choroid plexus. En bloc resection of an intact colloid cyst was described in early surgical reports, starting in 1948 with Greenwood. Keeping the contents within the cyst without aspiration and delivering the whole cyst from the third ventricle to the lateral ventricle remains a popular technique and is practiced by many neurosurgeons during microsurgical resection. In our early endoscopic experience with 10 colloid cyst resections, we observed that the cyst capsule slightly adheres to the ependyma of the roof of the third ventricle or foramen of Monro. After the cyst’s contents are aspirated, the capsule is pendulous and floats between the lateral and third ventricles because of cerebrospinal fluid pulsation. Usually, there is a single attachment to the choroid plexus at the roof of the third ventricle. Delivering the residual cyst from the third ventricle to the lateral ventricle has been described by many neurosurgeons (Figs. 12.8, 12.9). The surgeon must recognize that the roof of the third ventricle consists of five layers. The first, superior layer is the fornix, and the second is the superior membrane of the tela choroidea. Third is the vascular layer, which consists of the internal cerebral veins and the medial posterior choroidal artery and its branches. The fourth layer is the inferior membrane of the tela choroidea, and the fifth layer is the choroid plexus, which is in continuity with the choroid plexus of the lateral ventricle.52

Approaches to a Colloid Cyst: Transcranial vs. Endoscopic

The Cranial Approach for Resecting Colloid Cysts

Making the Decision

The Aim of Treatment

Topographical Features Relevant to Surgery

Choosing the Type of Surgery

Choosing the Surgical Approach

The Transcranial Approaches

The Transcallosal Approach

Avoiding Potential Complications

Endoscopic Resection of Third Ventricular Colloid Cysts

Background

Pathophysiology

Historical Perspective

Microsurgical Approaches

Anatomic Considerations: Pendulous Pathology

Endoscopic Resection: Signs for Safe Removal

The Roof of the Third Ventricle: Anatomic Layers and Variations

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Approaches to a Colloid Cyst: Transcranial vs. Endoscopic

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree