Much will be gained if we succeed in transforming your hysterical misery into common unhappiness.

I. THE GENERAL CLINICAL FEATURES OF CONVERSION DISORDER (FUNCTIONAL NEUROLOGIC SYMPTOM DISORDER)

A. Definition of conversion disorder

Conversion disorder (functional neurologic symptom disorder, DSM-5, 2013) means a temporary disorder of mental, voluntary motor, or sensory functions that mimics neurologic disease but is caused by unconscious determinants, not by organic lesions in the neuroanatomic sites that should produce the dysfunctions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder remains problematic for the clinician (Allanson et al, 2002; LaFrance, 2009; Nicholson et al, 2011). Table 14-1 reviews some common dysfunctions in patients with conversion disorder (functional neurologic symptom disorder). Malingering is not considered a mental illness.

TABLE 14-1 • Symptoms and Signs of Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder

A. Mental 1. Pseudoepileptic seizures 2. Amnestic and fugue states B. Motor 1. Paralysis (monoplegia, paraplegia, or hemiplegia) 2. Hyperkinesia: tremors, flailing, and spasms 3. Astasia–abasia 4. Aphonia–dysphagia 5. Hyperventilation, often with dizziness and syncope; weak, shallow respiration; or grunting, demonstrative respiration 6. Blepharospasm, convergence spasm, pseudo-VIth nerve palsy, and ptosis C. Sensory 1. Anesthesia, paresthesia, hyperesthesia, or pain 2. Dimness of vision, tunnel vision and spiral fields, blindness, double vision, and photophobia 3. Deafness and dizziness 4. Globus hystericus 5. Multisystem complaints, especially gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and reproductive system/sexual/menstrual 6. Urinary retention |

B. Primary and secondary gain

Classic psychoanalytic theory holds that functional neurologic symptom disorders arise from unconscious mental mechanisms that relieve overwhelming anxiety by converting it into symptoms (Meyers and Volbrecht, 2003; Weintraub, 1995; Woolsey, 1976). The symptom provides primary and secondary gains for the Pt.

1. The primary gain consists of the relief of anxiety.

2. The secondary gains consist of manipulative control over the emotional responses, attention, and actions of other persons and relief from responsibilities. Apparently, the gains make the symptom more acceptable to the Pt than the anxiety that the symptom relieves.

3. Walker et al (1989) suggested that operant conditioning, with its theory of reinforcement of behavior by reward, provides an alternative paradigm to psychoanalytic theory. They stated “Simply put, those behaviors that obtain reward are those that are expressed.”

C. Distinction between conversion disorder, factitious disorder, and malingering

1. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) distinguished between conversion disorder factitious disorder, and malingering for Pts who had symptoms and signs not caused by organic disease (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The DMS-IV Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) recognized three main types of factitious disorders: (1) factitious disorders with predominantly psychological signs and symptoms, (2) factitious disorders with predominantly physical signs and symptoms, and (3) factitious disorders with combined psychological and physical signs and symptoms. Factitious disorder (formerly known as Munchausen syndrome) a chronic variant of factitious disorder with predominantly physical signs and symptoms means the deliberate production of signs and symptoms to assume the role of a sick person. Often the Pt has had multiple surgical procedures that have failed to disclose an organic lesion or to affect a cure (American Psychiatric Association; 2000).

2. A large spectrum of symptoms and signs, such as nonepileptic seizures and many chronic pain syndromes, can occur as a functional neurologic symptom disorder in one Pt or as malingering in another. Rather than debating the question of the conscious or unconscious origin of the symptoms, the examiner’s (Ex’s) immediate operational task is to differentiate the nonorganic disorders of whatever origin from the known and diagnosable organic disorders. This is always the first dichotomy in diagnosis: Is the disorder nonorganic or organic? (Is there a lesion? See Table 15-3.) Careful selection of terms is important because of medicolegal considerations and because Pts have access to their own medical records, and are entitled to an understanding, empathetic physicians (neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists and general practitioners) working in collaboration. Criteria for functional neurologic symptom disorder (formerly known as conversion disorder) were modified to emphasize the essential importance of the neurological examination, and in recognition that relevant psychological factors may not be demonstrable at the time of diagnosis (DSM-5, 2013).

D. DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder

1. Learn Table 14-2.

TABLE 14-2 • Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Neurologic Symptom Disorder

1. | The patient has ≥1 symptoms of altered voluntary motor or sensory function |

2. | Clinical findings provide evidence of incompatibility between the symptoms and recognized neurological or medical conditions. |

3. | The symptom or deficit is not better explained by another medical or mental disorder. |

4. | The symptom or deficit causes clinically significant distress or impairment in sound, occupational, or other important areas of functioning or warrants medical evaluation. |

2. The medical history in functional neurologic symptom disorder

a. Women, usually between 10 and 35 years of age, predominate at about 3:1. However, the quoted ratio may reflect a diagnostic bias.

b. The history discloses longstanding personality problems, with some immediate emotional stress that triggers the index event. A history of other medically unexplained symptoms, predisposing emotional problems, and of the precipitating event is essential to the diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder. Do not diagnose functional neurologic symptom disorder in a previously well-adjusted 60-year-old Pt who suddenly has neurologic symptoms. Always assume that such a Pt has organic disease until proven otherwise.

c. During the interview or neurologic examination (NE), when the Ex focuses on the dysfunction, such as a tremor, it worsens. The dysfunction also worsens in the presence of family members or significant acquaintances. The symptom varies with the attention directed to it or with the presence of emotionally significant people. It is socially dependent. Remember, however, that emotional stress may similarly enhance organic tremors and involuntary movements.

3. The diagnosis of functional neurologic symptom disorder rests on two pillars

a. Pillar 1: The negative pillar is the absence of neurologic signs that would have to be present if an organic lesion caused the disability.

b. Pillar 2: The positive pillar is the history of overt psychiatric stress and the complete resolution of the symptoms with time as the psychiatric problems resolve.

E. Affective status in functional neurologic symptom disorder

1. No single affect or personality pattern accompanies conversion disorder (Woolsey, 1976). Some Pts appear blandly indifferent (la belle indifférence) to the disability by accepting it stoically or good-naturedly, as it were. However, the usefulness of this clinical sign is controversial (Stone et al, 2006) and not useful in distinguishing between functional neurologic symptom disorder and organic disease. Pts do not ask about or seem concerned about the cause or prognosis.

2. In contrast to the bland indifference of some Pts, others with neurologically unexplained symptoms, particularly sensory ones, such as pain, overreact histrionically, with much wailing or dramatic prostration. The art of diagnosis—the art—is to recognize the disproportionate underreaction or overreaction.

3. Caveats for the history

a. In searching for psychiatric stressors, the naive Ex may overlook the high achiever syndrome. Consider the Super-Kid or All-American Kid syndrome. The Pt, a straight-A student, runs cross country in the fall, plays varsity basketball in the winter, plays Little League baseball, swims competitively in the summers, and receives the yearly citizenship award at school. After school hours, the child goes to choir practice and baby-sits for the mother on weekends. The overscheduling denies the child a childhood. In desperation, the child becomes paraplegic. In such a Pt, the unremitting excellence of function, maintained at too high a cost in psychic energy, constitutes the psychiatric predisposition.

b. Some Pts with multiple sclerosis, frontal lobe damage, anosognosia, abulia, or Anton cortical blindness may seem blandly unconcerned about their disability and its implications.

II. PSYCHOGENIC DISORDERS OF MOTOR FUNCTION

A. Range of motor disorders

1. The proposal has been made to change the term psychogenic movement disorder to functional movement disorder (Edwards et al, 2014). Somatoform disorders may cause paresis, paralysis, hypokinesia, or hyperkinesia. Handedness does not influence lateralization of the observed motor abnormalities, and unilateral motor and sensory symptoms are as common on either side of the body (Butler and Zeman, 2005; Stone et al, 2002). The hyperkinesias usually take the form of tremor, spasms, or flailing about. The paralysis may affect cranial nerve muscles, causing aphonia or dysphagia, or it may affect the rest of the body in monoplegic, hemiplegic, or paraplegic distributions. Motor conversion disorders presenting as quadriplegia virtually never occurs (Video 14-1).

Video 14-1. Psychogenic movement disorder.

2. Psychogenic impotence, a very common form of psychogenic dysfunction, does not qualify as functional neurologic symptom disorder, because it represents failure of autonomic function rather than volitional muscular activity.

B. Psychogenic oculomotor signs

1. Some oculomotor manifestations: Excessive blinking, squinting or blepharospasm, convergence spasm, pseudo-VI nerve palsy, and pseudoptosis.

2. Convergence spasm: The pupils constrict along with the forceful adduction of the eyes, indicating an overactive accommodation mechanism (Griffin et al, 1976). Review accommodation in Table 4-3.

TABLE 14-3 • Differentiation of Psychogenic and Organic Paraplegia

Nonorganic paraplegia | Organic paraplegia | |

Onset | Usually arises suddenly after stress in a person with a psychiatric predisposition | May evolve slowly or suddenly in a patient with a predisposing organic cause |

Attitude to illness | May seem indifferent or histrionic | Appropriate concern |

MSR | Present and normal | Absent in spinal shock or very brisk |

Clonus | Absent or unsustained | Sustained |

Muscle tone | Normal | Flaccid acutely, then spastic |

Plantar response | Normal plantar flexion of great toe | Dorsiflexion of great toe unless spinal shock is present |

Abdominal/cremasteric reflex | Present | Absent, depending on level |

Umbilical migration | Absent | Upward migration if lesion affects T10 (Beevor sign) |

Sensory level | Extends horizontally around waist; variable; differs from motor level | Slants obliquely downward; constant border if lesion static |

Inadvertent | May move legs inadvertently for postural support, in sleep, or with Hoover test | Does not move legs if the paraplegia complete but may show flexor spasms |

Sphincter control | Present | Lost |

Anal wink reflex | Present | Lost in stage of spinal shock |

MRI, SSEV, and cystometrogram | Normal but usually not needed | Abnormal |

ABBREVIATIONS: MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MSR = muscle stretch reflex; SSEP = somatosensory evoked potentials. | ||

3. Pseudoabducens nerve palsy: The Pt, on attempting to look to one side, say the right, will move the eyes conjugately to, or a little past, the midline. Then the abducting, that is, leading, eye deviates inward, as if the lateral rectus muscle had failed. The adducting, that is, following, eye continues to progress to the right. Careful inspection will show that the Pt has learned to use convergence, as in volitionally looking cross-eyed. When the leading eye breaks from its abducting movement to the right, the pupils simultaneously constrict. Thus a volitional convergence stimulus has arrested the abduction of the eye, not weakness of the lateral rectus muscle (Troost and Troost, 1979). In organic VI nerve palsy, the failure of abduction does not cause pupilloconstriction.

4. Pseudoptosis: In organic ptosis, the Pt tends to lift the eyebrow up, using the action of the frontalis muscle. In pseudoptosis, the voluntary contraction of the orbicularis oculi causes the eyebrow to descend. The contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle may be extreme enough to cause blepharospasm. Pts with pseudoptosis may also use mydriatic drops to dilate the pupil, further simulating a III nerve palsy (Keane, 1982).

5. Caveats: Blepharospasm more commonly occurs secondary to dystonia or to ocular inflammation with photophobia. When organic disease causes convergence spasm, the Pt usually has other midbrain and pretectal signs (Table 5-2). Tourette syndrome may cause a variety of tics affecting the eyelids and causing excessive blinking.

6. Describe some associated findings or neighborhood signs if an organic lesion causes convergence spasm.

_________

_________

7. Describe the critical finding that distinguishes a pseudoabducens palsy from an organic palsy.

_________

_________

C. Psychogenic dysfunctions of voice production, swallowing, and breathing

1. Range of dysfunction: Mutism or low voice volume, dysphagia, and respiratory dysrhythmias.

2. Psychogenic mutism: Pts with conversion muteness may exhibit complete mutism or speak with a low voice volume. Although aphonic, the Pt has normal vocal cord action during laryngoscopy or shows pure adductor palsy, but the Pt can produce a Valsalva maneuver or a normal strong cough, proving that the adductor muscles of the vocal cords can, in fact, act forcefully. The Pt has no palatal palsy, breathes and swallows normally, and may whisper with perfect articulation. The Pt may talk or phonate during sleep, thus establishing the integrity of the vocal apparatus.

3. Spasmodic dysphonia: When the Pt attempts to speak, the vocal cords go into spasm, causing a tight, hoarse, or strained voice (Aminoff et al, 1978).

4. Psychogenic dysphagia: The Pt chokes, or cannot swallow, but may have no accompanying signs of palatal, laryngeal, or pharyngeal dysfunction. The Pt swallows normally when asleep. The Pt may also experience globus hystericus, a distressing sensation of a lump lodged in the throat.

5. Respiratory dysrhythmias: Disorders include apnea, often in association with a Valsalva maneuver, hyperventilation, weak, shallow, or “asthenic” breathing in a Pt who avoids eye contact, or theatrical gagging, with guttural noises, stridor, rolling of the head and trunk and demonstrative, expressive eyes (Walker et al, 1989). Walker and colleagues (1989) likened the latter state of respiratory gymnastics to astasia and abasia: in both states, the Pt flirts with disaster but escapes. Hyperventilation may accompany or precede hysterical symptoms such as dizziness in Pts with somatic symptom disorder. Most Pts with psychogenic breathing disorders show no cyanosis and have a normal arterial O2 but, if misdiagnosed, may be mistakenly intubated (Walker et al, 1989).

6. Caveats: Dystonia may cause spasmodic dysphonia. Early stages of several organic diseases—such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and myasthenia gravis—may cause dysphonia and dysphagia without other signs early in the course of the diseases. Always consider myasthenia gravis when the Pt has any unexplained weakness of bulbar muscles. Semirhythmic contractions of the abdominal wall and diaphragmatic flutter may be secondary to “belly dancer’s” dyskinesia (Iliceto et al, 2004). Dyphagia lusoria may be associated with an aberrant right subclavian artery. A review of patients previously diagnosed with psychogenic dysphagia showed that a medical cause was found in two-thirds of cases (Ravich et al, 1990).

D. Psychogenic vomiting

In Pts with functional neurologic symptom disorder, the vomiting occurs mainly in the presence of emotionally significant people. Some Pts may simulate gastrointestinal bleeding by secretly adding blood to their vomitus or stool. The Pt with anorexia nervosa or bulimia vomits in the bathroom or in secret.

E. Psychogenic disturbances of station and gait

1. General features of astasia–abasia: Most common gait disorders are hemiparetic, paraparetic, ataxic, or trembling gait (Keane, 1989), and astasia–abasia. Astasia means the inability to stand, and abasia means the inability to walk. Taken together the two words imply total inability to stand and walk, but often with the Ex’s suggestion the Pt may attempt to do so (Keane, 1989). Patients with atasia–abasia show wild gyrations when standing or walking. The Pt rarely falls, or falls into the Ex’s arms (or a chair) without suffering bodily injury. The flamboyant gyrations without falling testify eloquently to the competency of the Pt’s motor system and balance (Video 14-2). When in bed or sitting, the Pt may show no disability or only minor disturbances of movement. On the Romberg test, the Pt will usually sway much more with the eyes closed.

Video 14-2. Psychogenic gait.

2. Hemiparetic and hemiplegic gaits: In psychogenic hemiplegia, the lower part of the face ipsilateral to the hemiplegia is not involved; the protruded tongue, if it deviates at all, deviates toward the normal side (Keane, 1986). Tongue deviation is uncommon in organic hemiplegia, but when it occurs the deviation is to the hemiplegic side. The arm and leg do not assume true hemiplegic postures when the Pt is at rest or when walking (Fig. 12-15; Keane, 1989). The leg of the organic hemiplegic turns outward when the Pt is recumbent. The abdominal, plantar, and muscle stretch reflexes are always normal. The hand is not preferentially affected as in organic hemiparesis.

3. Dragging monoplegic gait: The Pt walks with the good leg forward and the monoplegic limb dragging behind. The foot may be turned out or inverted or everted (Stone et al, 2002). Sudden buckling of the knee is also common.

4. Psychogenic paraplegia: Key differences on the NE are the presence of normal abdominal or cremasteric, muscle stretch, and plantar reflexes, normal muscle tone, and retention of bowel and bladder control in psychogenic paraplegia and their usual impairment in organic paraplegia (Baker and Silver, 1987).

a. Sensory changes tend to be highly variable, may not match the motor level, and do not show the dissociated loss between anterolateral and dorsal columns or the sacral sparing that may characterize organic paraplegia (Table 14-3).

b. The T10 level of the spinal cord supplies the umbilical level of the abdomen (Fig. 2-10). With organic paraplegia from a T10 level lesion, the skeletal muscles of the lower two quadrants of the abdomen are paralyzed along with all other muscles distal to T10. The upper quadrant skin-muscle reflexes will be preserved but absent in the lower two quadrants. The Pt shows Beevor sign when attempting to do a sit-up, that is, the intact upper quadrant abdominal muscles cause the umbilicus to migrate upward because of no corresponding anchoring pull from the muscles of the paralyzed lower quadrants. This sign never occurs in psychogenic paraplegia.

5. Caveats: Recall that Pts with the rostral or caudal vermis syndromes may show little dysfunction when reclining but display dystaxia when walking, particularly when tandem walking. Camptocormia (bent spine syndrome), initially attributed to a psychogenic disorder, can have many causes including a variety of neuromuscular disorders, flexion dystonia of the trunk, axial myopathy, and parkinsonism. The disorder is characterized by forward flexion of the trunk present in the standing position, increasing during walking, and abating in the supine position (Lenoir et al, 2010) Patients with involuntary movement syndromes, in particular dystonia musculorum deformans, frequently get diagnosed as having a psychogenic disorder in the early stages of their illness. Astasia–abasia has also been related to normal pressure hydrocephalus. Status cataplecticus (“limp man syndrome” due to narcolepsy has been mistaken for a psychogenic disorder (Simon et al, 2004). See the gait essay at the end of Chapter 8.

F. Techniques and observations that separate psychogenic paresis or paralysis of trunk and limbs from organic paralysis

1. Demeanor of the Pt: The Pt’s demeanor during testing of strength often provides a clue to psychogenic weakness. Usually the Pt with psychogenic paralysis makes a great show of effort to move the afflicted part, but to no avail. Thus, the Pt may grimace, grunt, or squirm, and show obvious strain, but the part does not move. It is a dramatic performance meant to communicate sincerity of effort, rather than a simple attempt to move the part, as in organic paralysis. The patient with somatic symptom disorder with partial paralysis usually moves the part very slowly. Often the Ex can see and feel that the putatively weak muscles in such a movement in fact contract very strongly. Thus, in grip testing, the Pt often co-contracts the flexors and extensors very strongly, demonstrating intact innervation, which the Ex can see and palpate. Because the Pt contracts all muscles isometrically, the Pt’s fingers only encircle the Ex’s fingers very lightly, not actually closing tightly on them. When the Ex tugs against a muscle to test strength, the Pt may offer considerable resistance and then yield suddenly, or may show a series of jactitating, cogwheel-like releases. Objective recording of strength by myometry shows different patterns of contractions in psychogenic weakness, normal individuals, and organically paralyzed Pts (van der Ploeg and Oosterhuis, 1991).

2. Distribution of psychogenic paralysis: Although the psychogenic paralysis may follow monoplegic, hemiplegic, or paraplegic distributions, it seldom affects individual muscles or groups of muscles innervated by one peripheral nerve or root. The limbs do not assume organic postures, as in organic hemiplegia, and the overall lack of signs, particularly the normal reflexes, establishes the psychogenic nature of the paralysis.

3. Eliciting inadvertent or automatic movements (synkinesias) of the paralyzed parts in psychogenic motor disorders

a. Sleep: Several inadvertent or synkinetic movements establish the integrity of the putatively paralyzed part. The Pt with psychogenic monoplegia, hemiplegia, or paraplegia moves the parts in the normal manner during sleep. When dressing the Pt may inadvertently reach out with the affected part or use it automatically for postural support. This is a key principle: The Ex finds some way to activate the putatively paralyzed muscles inadvertently or synkinetically.

b. Monrad-Krohn cough test for arm monoparesis (1922): To identify psychogenic paralysis of the arm, the Ex stands behind the Pt and grasps the two latissimus dorsi muscles between the thumb and fingers of the right and left hands. The Ex asks the Pt to cough forcefully. Both latissimus dorsi muscles synkinetically contract strongly, thus establishing the integrity of the motor pathway through the brachial plexus.

c. Double-crossed-arm pull test for psychogenic arm monoparesis

i. When required to use both sides simultaneously and unexpectedly, the psychogenic Pt will generally inadvertently contract the putatively weak side along with the normal side.

ii. Start with the Pt upright and the forearms crossed and flexed (Fig. 14-1). If the Pt’s arm is completely paralyzed, hold it in place.

iii. While holding the Pt’s forearms as shown in Fig. 14-1, say: “When I say now, try to pull back strongly away from me, and I will hold you in place.” Then say now after a brief pause. Usually, the Pt braces the paretic and nonparetic arms when pulling back.

FIGURE 14-1. The double-crossed-arm pull test for psychogenic paresis of one arm. The examiner’s hands grip the patient’s forearms. See text for instructions.

d. Make-a-fist test for psychogenic wrist drop

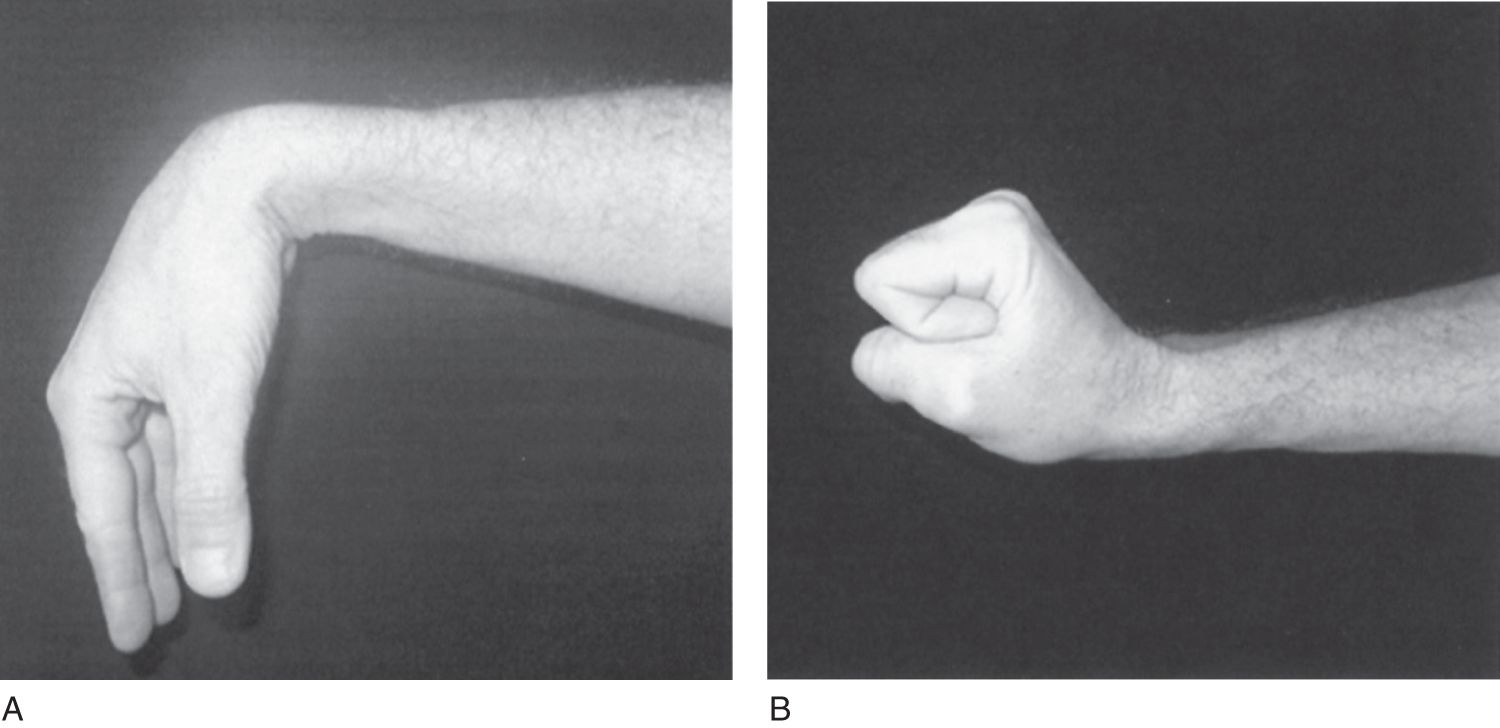

i. To distinguish a psychogenic wrist drop from a radial nerve palsy, ask the Pt to extend the arm out straight. The putatively paralyzed wrist hangs limply (Fig. 14-2A).

ii. Instruct the Pt to suddenly make a strong fist when you say now.

iii. If intact, the putatively paralyzed wrist extensors automatically cock the hand up into the “anatomic position” when the Pt makes a fist (Fig. 14-2B). Try this test yourself. In a true radial palsy, the wrist does not cock up.

iv. As a refinement of the test, ask the Pt to grip a screwdriver or rod strongly or to grip the rod strongly with both hands simultaneously.

FIGURE 14-2. Make-a-fist-test for psychogenic wrist drop. (A) With the forearm extended, the patient has an apparent wrist drop. (B) When the patient makes a fist, the wrist automatically dorsiflexes, proving that the extensor muscles are intact.

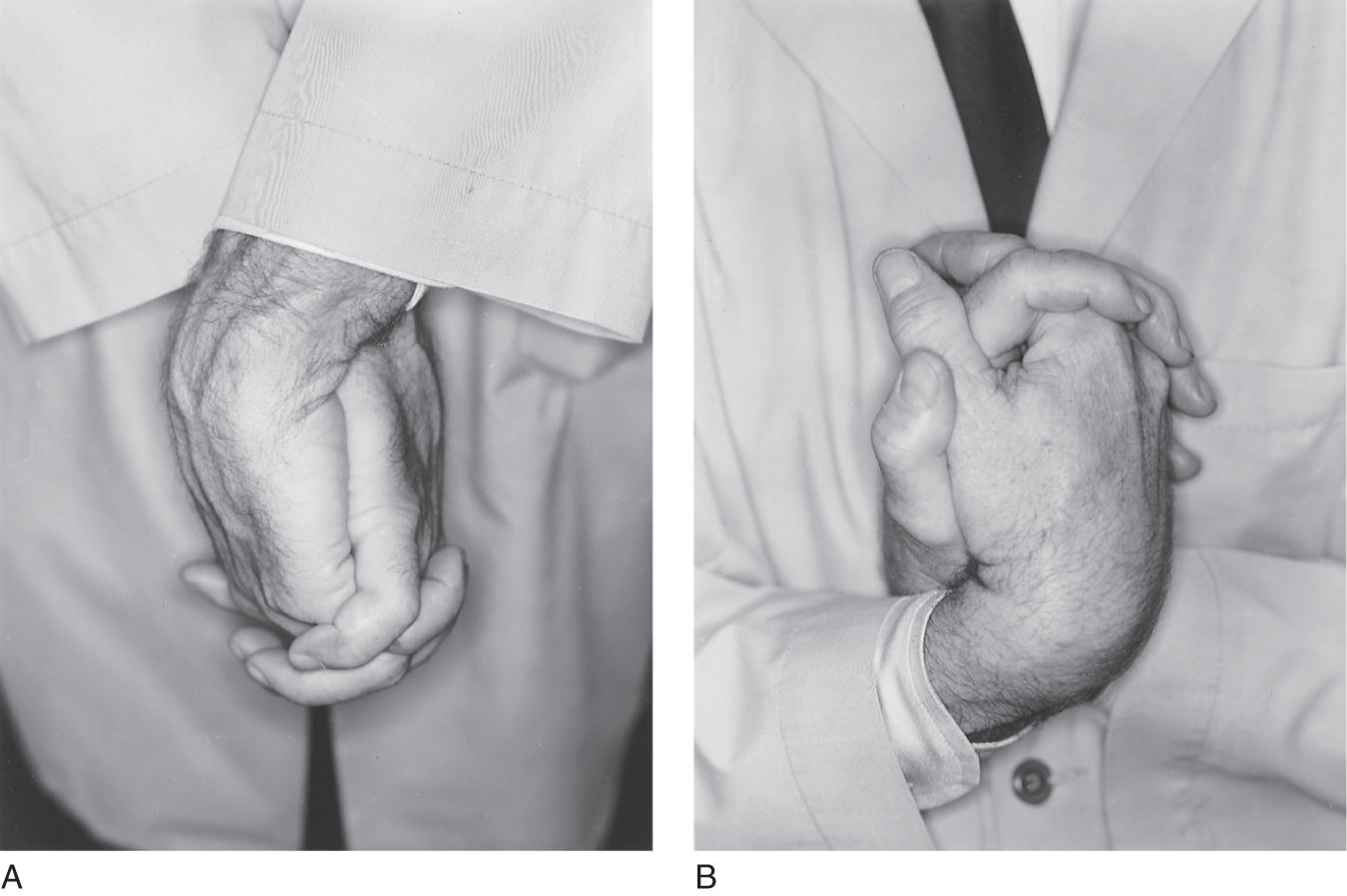

e. Reversed hands test for arm monoparesis

i. To identify psychogenic hand paralysis, the Ex has the Pt reverse and invert the hands (Figs. 14-3A and 14-3B).

ii. Then ask the Pt to look at the fingers. The Ex then points to but does not touch a finger and asks the Pt to move that finger. Usually, the Pt moves the finger of the hand opposite to the one pointed to by the Ex. Try this test on a partner. After a few trials, the subject learns to respond accurately. Thus, the test serves best during the first trials. The test also works for psychogenic anesthesia. With the Pt’s eyes closed, the Ex actually touches the finger of one hand or the other. The Pt usually moves the finger of the putatively anesthetic hand.

FIGURE 14-3. Inverted-hands test for psychogenic loss of sensation or motor function. (A) Clasp fingers as shown, with hands crossed and palms together. (B) Invert the hands. The final posture in B reverses right for left. See text for further Instruction.

f. Backward displacement test for psychogenic foot drop

i. To distinguish a psychogenic foot drop from a peroneal nerve palsy, ask the Pt to stand with the eyes closed.

ii. Place one hand flat on the Pt’s sternum and suddenly displace the Pt backward, using the other hand on the Pt’s back to prevent a fall.

iii. The Ex will see the dorsiflexor tendons of the feet spring into action as the Pt automatically reacts to the displacement.

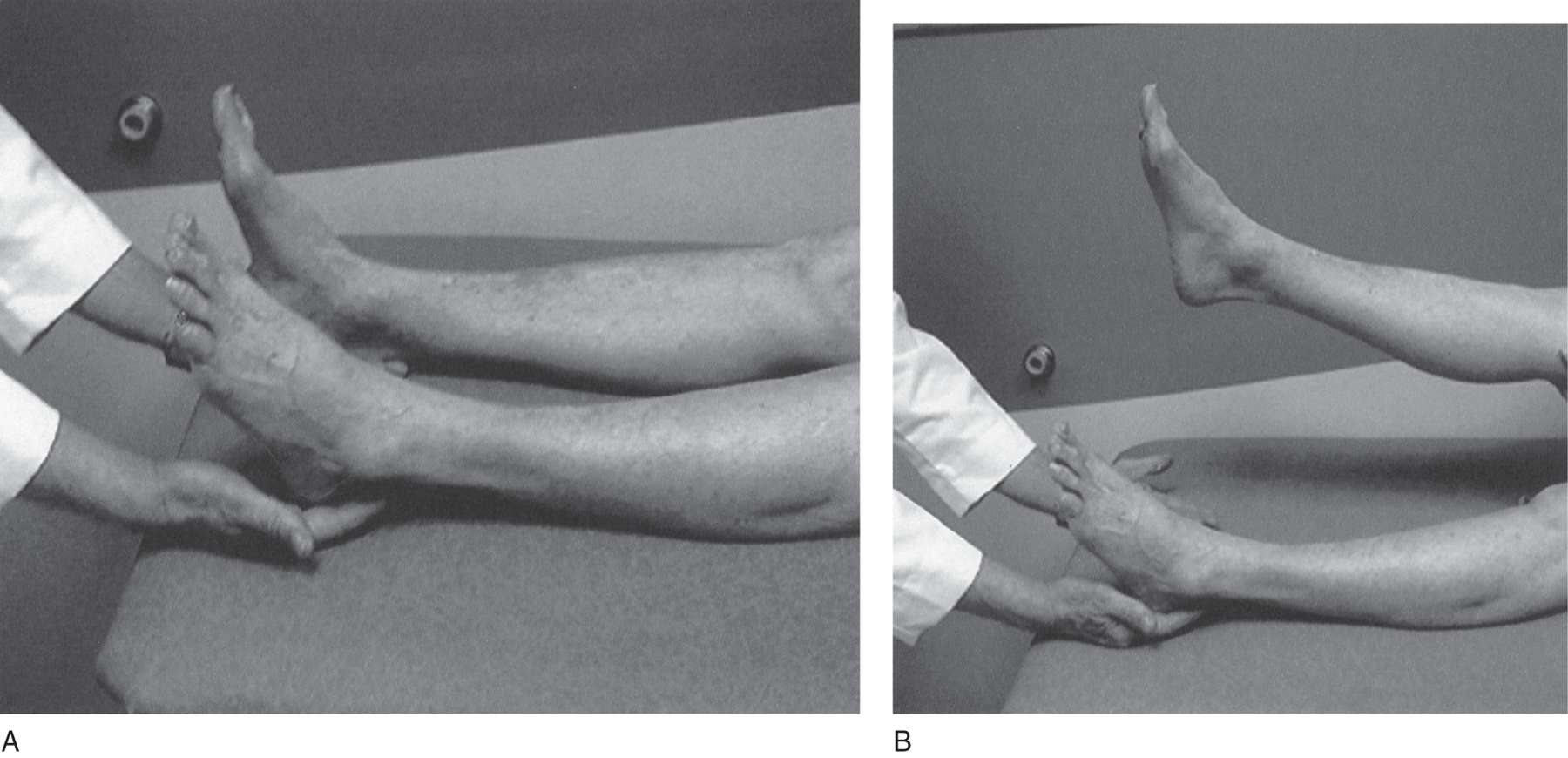

g. Hoover test for psychogenic leg monoparesis

i. With the Pt recumbent, stand at the foot of the examination table with one palm under each of the Pt’s heels (Fig. 14-4A).

ii. Ask the Pt to press down with the putatively paretic leg. The heel will not press down on the Ex’s palm.

iii. Ask the Pt to lift the normal leg up briskly in one motion. The paretic leg will press down against the Ex’s palm as an automatic, synkinetic counteraction that the Ex can feel and see (Fig. 14-4B; Stone et al, 2002).

iv. Ask the Pt to press down with both heels. Usually the Pt with psychogenic paralysis presses down with both heels, whereas the Pt with organic paralysis does not.

v. As a refinement of this test, place one hand under the paralyzed limb, press down on the knee of the sound limb, and instruct the Pt to lift it as strongly as possible. The putatively paralyzed limb will synkinetically press down.

FIGURE 14-4. Hoover leg-elevation test for psychogenic paralysis of one leg. The examiner places a hand under each of the patient’s heels. Then the examiner asks the patient to forcefully raise the normal leg. The patient will inadvertently push down with the putatively paralyzed leg.

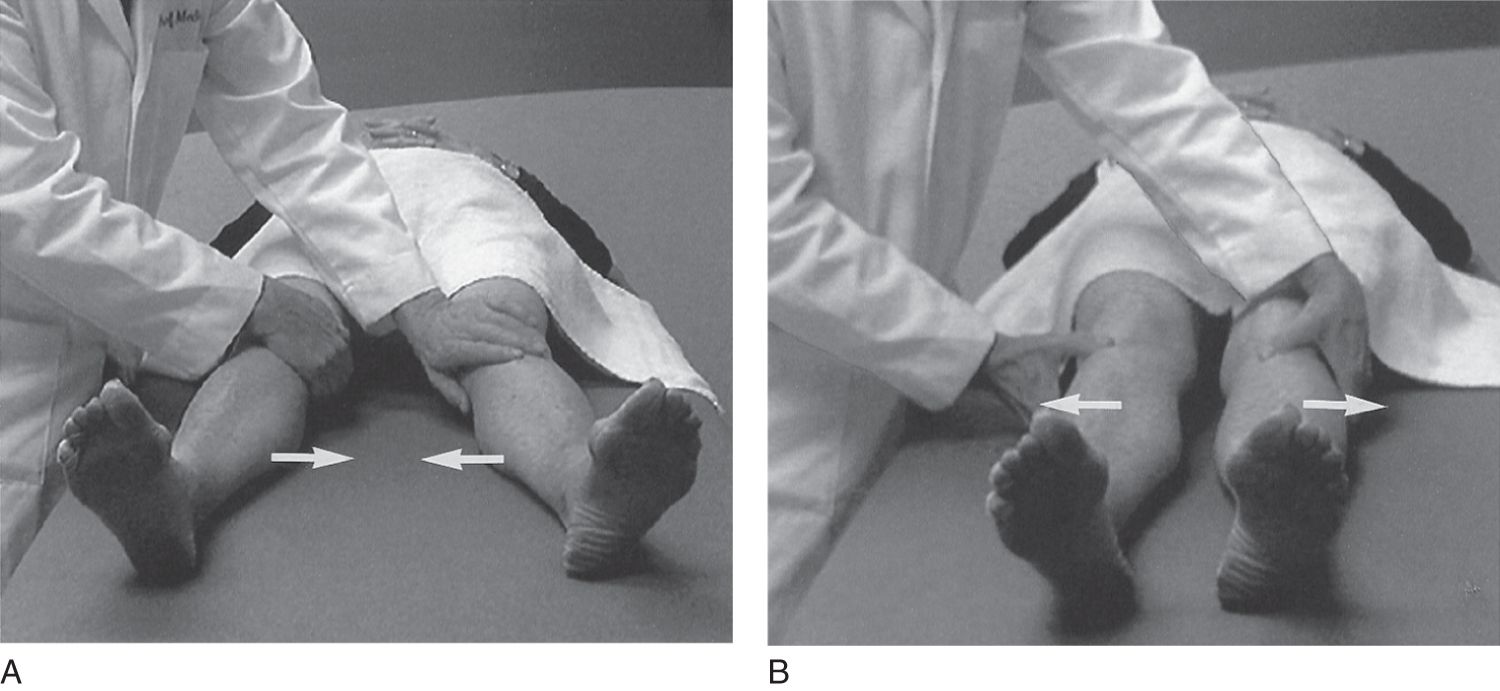

h. Raimiste leg adduction–abduction synkinesis for psychogenic leg monoparesis

i. The same principle of inadvertent synkinetic bracing of the putatively paralyzed part applies in testing adduction and abduction of the legs.

ii. With the Pt recumbent, place your hands on the Pt’s knees and ask the Pt to squeeze the legs together strongly as you hold your hands in place, in opposition to the Pt’s action (Fig. 14-5A).

iii. The Pt usually braces the putatively paralyzed limb in automatic opposition to the action of the intact limb.

iv. Similarly, ask the Pt to press the legs apart strongly against your manual resistance. The putatively paralyzed limb usually will abduct in automatic opposition (Fig. 14-5B).

FIGURE 14-5. Raimiste leg-adduction and -abduction test for psychogenic leg paresis. (A) The patient tries to adduct, that is, squeeze both legs strongly together (arrows) against the examiner’s manual opposition. (B) The patient tries to abduct, that is, separate both legs strongly (arrows) against the examiner’s manual opposition. In each case, the patient synkinetically braces the putatively paretic leg.

4. Review of formal tests to produce synkinetic movements of putatively paralyzed muscles in Pts with psychogenic weakness

a. Describe the Monrad-Krohn cough test for psychogenic brachial plexus/arm paralysis. _________

b. Name the muscle tested in the foregoing test _________

c. Test for psychogenic arm monoparesis (double pull test).

_________

d. Test for psychogenic wrist drop.

_________

e. What major nerve, when interrupted, causes a wrist drop? _________

f. Test for psychogenic foot drop._________

g. What major nerve, when interrupted, causes a foot drop?

_________

h. Test for psychogenic leg monoparesis (Hoover test). _________

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree