Concussion

James M. Noble

John F. Crary

INTRODUCTION

Concussion is a mild traumatic brain injury that has been recognized for centuries as an entity in accidents, battle, and sport. The visibility of higher profile cases of recurrent concussion in contact sports and growing concern of the potentially long-term impact of concussion, particularly among potentially vulnerable youth with developing brains, have brought concussion to the fore in recent years and perhaps rightfully so. In reflection of increasing concern, awareness, and research in the field, this chapter is the first version to appear into this established textbook.

DEFINITION

Concussion is a mild traumatic brain injury defined by a typically transient appearance of neurologic signs and symptoms, including headache, dizziness, imbalance, tiredness and fatigue, light and sound sensitivity, concentration difficulties, and memory impairment (often described as a brain “fog”), sleep disturbance, or mood disorder, following either a direct or indirect rapid movement in the brain causing extreme rotational or translational brain acceleration or deceleration injury. Loss of consciousness at the time of impact is not required to make a diagnosis of concussion. Additional symptoms of the time of impact may include transient visual disturbances or spontaneous visual hallucinations, commonly described to “seeing stars.”

Concussion can occur by any traumatic etiology including falls from a sufficient height, motor vehicle accidents, nonpenetrating blast injuries in the field of combat, domestic violence, or other physical traumatic events. Sport-related concussion (SRC) is defined as a concussion that occurs coincidentally during the play of a contact sport with a high risk of concussion (i.e., American football, soccer [European football], hockey, lacrosse, basketball, wrestling, and rugby, among others) or during combat sports, which are distinguished by having the specific goal of inducing a concussion in the opponent (boxing, mixed martial arts, and related sports). Regardless of the etiology of concussion, the symptoms are largely indistinguishable but may have differing psychosocial factors associated with recovery.

In contrast to other more advanced forms of traumatic brain injury, concussion lacks defining neuroradiologic features such as hemorrhage or other obvious abnormalities on conventional neuroimaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although several fluid-based biomarkers and electroencephalogram approaches are currently under study, none is presently used in part of standard of care practice. High-field MRI sequences including diffusion tensor imaging and functional MRI (fMRI), among others, hold promise in establishing the diagnosis of concussion or perhaps even subconcussive injuries in serially monitored individuals but these too are not part of current standard of care practice. Given substantial differences in these MRI sequences between individuals, the comparison of an individual against normative values has substantial limitations and thus currently limits the use of diffusion tensor imaging and fMRI principally to research rather than clinical practice.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The lifetime incidence of single and repeat concussion is not well known but is thought to occur in several million individuals annually in the United States alone. The epidemiology follows a trimodal pattern over lifetime with peaks in the first few months of life, followed by adolescence, and followed by a third peak in the elderly. Contributions to concussion etiology among the very young and very old likely principally relate to accidental falls, whereas concussions in adolescents may relate to risk-taking behaviors involving driving, exposure to violence, as well as exposure to increasingly competitive athletics. The annual incidence of SRC is at least 300,000 in the United States alone, although this is likely an underestimate given poor recognition by affected players. The epidemiology of recurrent concussion is not well described but is thought to happen in a small proportion of players previously affected by SRC.

PATHOBIOLOGY

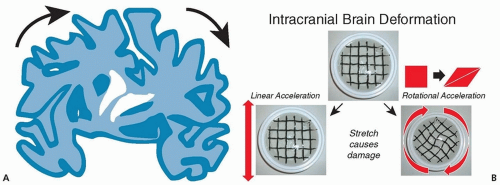

Given that concussion patients generally have no evidence of structural brain injury using conventional neuroimaging with MRI or CT, concussion has historically been considered a physiologic alteration, but this has become a matter of some debate. Concussion may reflect substantial physiologic disturbance with significant microstructural axonal disruption, which remains difficult to detect but nonetheless occurs. These injuries may be widespread or alternatively relatively focal but involving pathways with major widespread clinical implications. Experimental models suggest metabolic changes including elevated tissue lactate, which peaks over the course of several days followed by gradual recovery of cerebral blood flow within the affected tissues, with most demonstrable changes resolving by 7 to 10 days. In response to rotational or translational shear physical stress, animal histopathologic models of concussion demonstrate disruption of the viscoelastic properties of axons with rare disruption or lysis of axons themselves (Fig. 45.1).

When considering an individual experiencing a single concussion, injury thresholds required to cause concussion are not well understood but are thought to occur following at least 60 g of

linear acceleration or at least 2,000 to 4,000 rad/s2 rotational acceleration; these forces are seldom if ever experienced in the course of normal daily life outside of recognized physically traumatic events experienced by the affected individuals. At present, risks for concussion occurrence, severity, and recurrence are not well understood but suggest prior traumatic brain injury raises the risk of subsequent concussion. The highly variable nature of concussion expression and recovery raises the possibility of an unrecognized gene-environment risk profile.

linear acceleration or at least 2,000 to 4,000 rad/s2 rotational acceleration; these forces are seldom if ever experienced in the course of normal daily life outside of recognized physically traumatic events experienced by the affected individuals. At present, risks for concussion occurrence, severity, and recurrence are not well understood but suggest prior traumatic brain injury raises the risk of subsequent concussion. The highly variable nature of concussion expression and recovery raises the possibility of an unrecognized gene-environment risk profile.

DIAGNOSIS

All 50 states of the United States mandate that every individual having experienced a possible or suspected SRC must be evaluated by a licensed practitioner prior to returning to play. In contrast to SRC, in which players in conjunction with team coaches and athletic trainers bring the diagnosis to attention, concussion experienced in other contexts such as motor vehicle accidents or other causes of trauma are often diagnosed at the time that the individual is brought to attention for other matters related to bodily trauma. Although many concussion screening rubrics have been proposed, fundamentally, the diagnosis is based on a clinician’s suspicion that concussion has occurred based on neurologic symptoms, which should be typically without significant focal neurologic findings on examination. Any localizing or lateralizing signs or symptoms should prompt a clinician to consider neuroimaging, such as CT if the patient is suspected of having urgently declining neurologic condition or MRI if the patient is being assessed in a nonurgent setting or experiencing unexpectedly prolonged recovery of signs or symptoms following injury.

A number of devices and tools have been suggested to comprise concussion monitoring strategies, including questionnaires, complemented by a range of tests from simple reaction time to automated neuropsychological testing to more formal/conventional neuropsychological testing.

With the exception of formal neuropsychological testing, which has a significant disadvantage as a screening tool given its cost and time required, most if not all, other tests in this field were developed as a tool to assist in sideline assessments by nonmedical staff, with the intention of screening to limit the risk of prematurely returning a player to contact sport. However, they must be interpreted with substantial caution because they cannot supplant formal neurologic evaluation, which may capture subtleties not otherwise recognized on these screening assessments. Current consensus guidelines advocate the use of a standardized screening assessment, such as the Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool (third version) in the context of game play, but the validity of this and other screening tools in clinical contexts remain uncertain, and a comprehensive neurologic assessment should be pursued whenever concussion is suspected. Moreover, some screening assessments are considered normal within a relatively large range of values, are prone to retest bias, and may have limited generalizability beyond a relatively small reference population. Finally, most tests used in serial concussion monitoring programs are susceptible to “gaming” or “sandbagging” by a player eager to return to play, with baseline assessments purposefully performed poorly such that postconcussion assessments may not substantially differ.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree