30 Endoscopic Transnasal Craniectomy: Approaches to the Clivus and Posterior Fossa

Aldo Cassol Stamm, Shirley S.N. Pignatari, Eduardo Vellutini, Diego Hermann, and Daniel Timperley

Introduction

Introduction

Before the endoscopic era, the management of lesions in these regions required extensive craniotomies resulting in significant morbidity to patients.1,2 However, even with several endoscopic proposed approaches, effective and safe treatment of lesions involving these regions is still a challenge.3–7 The problems of infection, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, difficulty controlling intradural bleeding, lack of experience, and appropriate surgical instruments still exist.8 The combination of a team approach, with neurosurgery, otolaryngology, intensive care, anesthesiology, pathology, endocrinology, and paramedical staff, including specialist nursing, good patient selection, a thorough understanding of the anatomy, and appropriate expertise and equipment, facilitates extending the transnasal craniectomy approach to the clivus and posterior fossa.9

Indications and Advantages

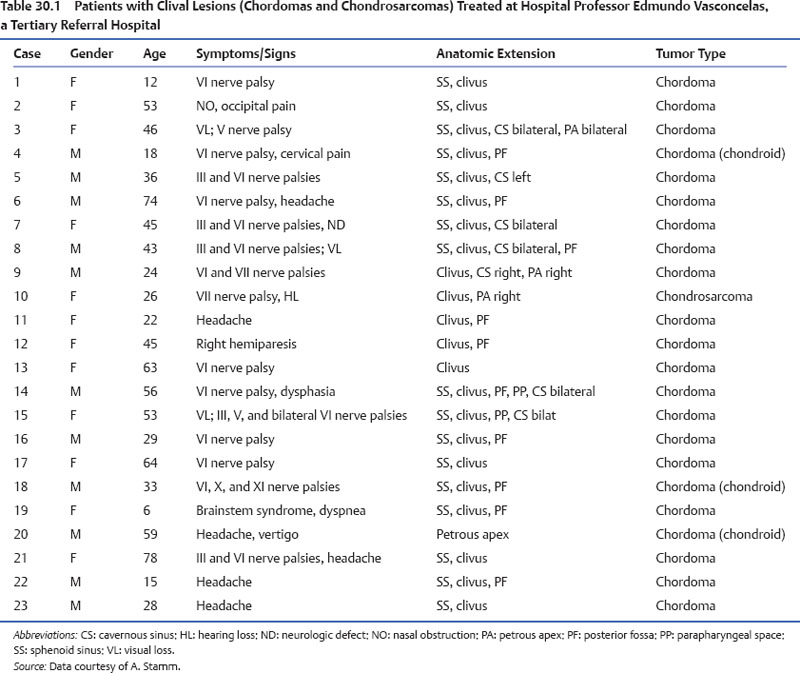

The endoscopic transnasal craniectomy approach to the posterior cranial fossa is used for lesions involving the clivus or retroclival region. The most common lesions for which this approach is indicated are clival chordomas and chondrosarcomas, followed by cholesterol granulomas and mucoceles (Table 30.1).

The advantages of this approach include the ability to avoid any cerebral retraction and to decrease the incidence of injury to the lower cranial nerves. In addition, the approach is direct, and does not require any external incisions.

Contraindications

Contraindications include patient comorbidities that might preclude them from prolonged general anesthesia; unfavorable anatomy, such as small sphenoid sinus or diminished space between the internal carotid arteries, which makes drilling the clival bone more difficult and risky; lack of multidisciplinary team cooperation and interaction; and lack of specialized equipment/instruments.

Diagnostic Workup

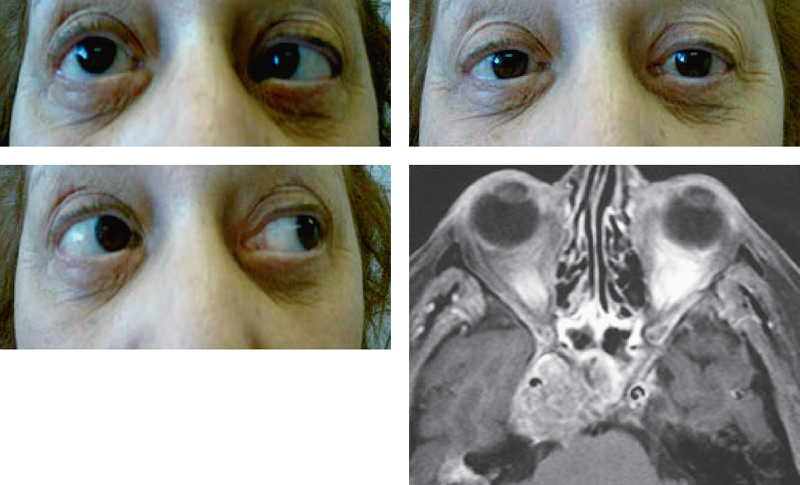

The physical examination includes neurologic assessment with a special focus on cranial nerve function. Endoscopic assessment of the nasal cavity is recommended to visualize any nasal lesions and document septal integrity, deviations, and other anatomical findings. An ophthalmologic examination is suggested if the optic nerve or orbital integrity is compromised, including a visual field examination (Fig. 30.1).

Imaging

Coronal, axial, and parasagittal computed tomography (CT) images of the paranasal sinuses and skull base are essential in the preoperative assessment for surgery. It is also necessary to evaluate the size of the sphenoid sinus, the position of the internal carotid artery, especially its paraclival portion, and the thickness of the clivus in the sagittal plane.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important to demonstrate the morphology of the soft tissues. Additionally, MRI should be evaluated for involvement of the carotid artery, vertebrobasilar system, and dural sinuses (Fig. 30.2).

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or CT angiography (CTA) can also be helpful to look at the relationship between the basilar and internal carotid arteries and the pathology. Particular attention should be given to the cavernous sinus, the inferior end of the superior intercavernous sinuses, and the basilar venous plexus.

Angiography can also be important to verify the functional integrity of the circle of Willis and the extent of any carotid artery compromise, and to differentiate an aneurysm from a tumor (Fig. 30.3).

Surgery

Instrumentation

Adequate instrumentation is paramount for the endoscopic approach to the clivus and posterior fossa. The necessary equipment includes high-quality endoscopes (0- and 45-degree); video equipment (camera and monitor); long endoscopic bipolar forceps, preferably suction bipolar; long and delicate drills; long dissection instruments; and hemostatic materials. In conjunction with Karl Storz Endoscopy (Flanders, NJ), the authors developed a 5-mm, wide-angle, 0-degree endoscope for these procedures to increase the field of view and illumination (Figs. 30.4 and 30.5).

Fig. 30.1 Example of sixth nerve examination. Note the palsy of the right abducens nerve. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrates tumor involving the right cavernous sinus.