TABLE 58.1 International League Against Epilepsy Classification of Epileptic Seizures | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

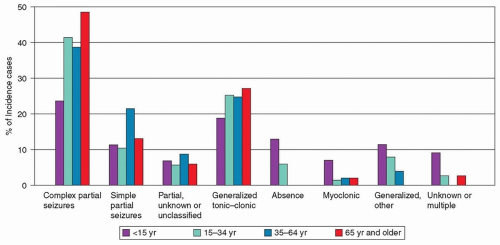

and evolving; clinical expression is determined as much by the sequence of spread of electrical discharge within the brain as by the area where the ictal discharge originates. Variations in the seizure pattern exhibited by an individual imply variability in the extent and pattern of spread of the electrical discharge. Both generalized and partial seizures are further divided into subtypes. For partial seizures, the most important subdivision is based on consciousness, which is preserved in simple partial seizures or lost in complex partial seizures. Simple partial seizures may evolve into complex partial seizures, and either simple or complex partial seizures may evolve into secondarily generalized seizures. In adults, most generalized seizures have a focal onset whether or not this is apparent clinically. For generalized seizures, subdivisions are based mainly on the presence or absence and character of ictal motor manifestations.

The patient may be amnesic after the seizure, with no memory of early events.

Consciousness may be impaired so quickly or the seizure may generalize so rapidly that early distinguishing features are blurred or lost.

The seizure may originate in a brain region that is not associated with an obvious behavioral function. Thus, the seizure becomes clinically evident only when the discharge spreads beyond the ictal-onset zone or becomes generalized.

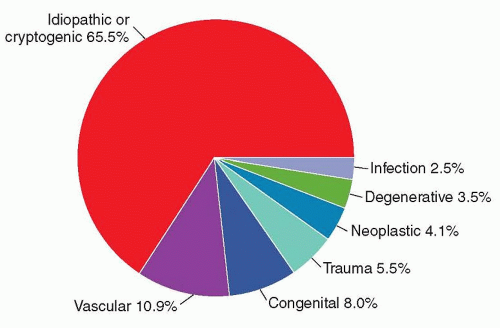

or specific etiologic information. This classification is useful for some reasonably well-defined syndromes, such as infantile spasms or benign partial childhood epilepsy with central-midtemporal spikes, especially because of the prognostic and treatment implications of these disorders. On the other hand, few epilepsies imply a specific disease or defect. A further drawback to the ILAE classification is that the same epileptic syndrome (e.g., infantile spasms or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome) may be “symptomatic” of a specific disease (e.g., tuberous sclerosis), considered “cryptogenic” on the basis of nonspecific imaging abnormalities, or categorized as “idiopathic.” Another biologic incongruity is the excessive detail in which some syndromes are identified, with specific entities culled from what are more likely simply different biologic expressions of the same abnormality (e.g., childhood and juvenile forms of absence epilepsy). As a result, a new classification of epilepsy syndromes has been proposed and is presently under discussion (Engel, 2006).

TABLE 58.2 Modified Classification of Epileptic Syndromes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Brief seizures that begin and end abruptly with little, if any, postictal period

A tendency for seizures to cluster and to occur at night

Prominent, but often bizarre, motor manifestations, such as asynchronous thrashing or flailing of arms and legs; pedaling leg movements; pelvic thrusting; and loud, sometimes obscene, vocalizations, all of which may suggest psychogenic seizures (Video 58.4)

Minimal abnormality on scalp EEG recordings

A history of status epilepticus

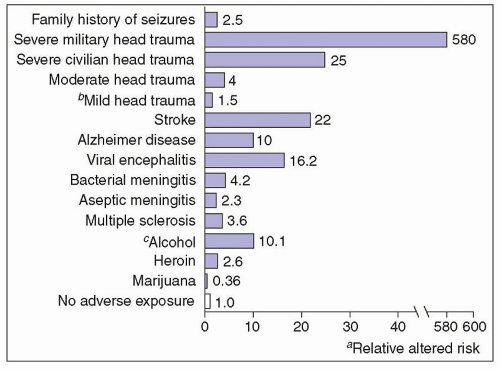

levels in another. Head injuries are classified as severe if they result in brain contusion, intracerebral or intracranial hematoma, unconsciousness, or amnesia for more than 24 hours or in persistent neurologic abnormalities, such as aphasia, hemiparesis, or dementia. Mild head injury (brief loss of consciousness, no skull fracture, no focal neurologic signs, no contusion or hematoma) does not increase the risk of seizures significantly above general population rates.

TABLE 58.3 Predictors of Intractable Epilepsy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

may be uninformed about, or may not recall, early childhood events, such as perinatal encephalopathy, febrile seizures, brain infections, head injuries, or intermittent absence seizures. Age at seizure onset and course of the seizure disorder should be clarified because these features differ in the various epilepsy syndromes.

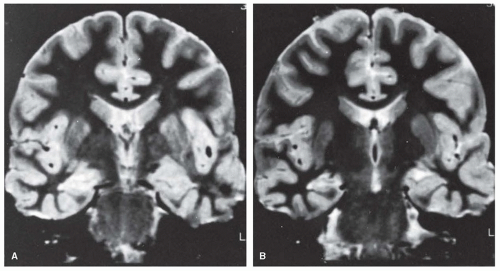

positron emission tomography (PET) scans can add valuable localizing information, especially when the MRI scan is negative. Singlephoton emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans are also used, although resolution is less than either MRI or PET. Subtraction ictal SPECT co-registered with MRI (SISCOM) is also helpful in localizing the epileptogenic brain region in some cases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree