Frontotemporal Dementia

Edward D. Huey

Stephanie Cosentino

INTRODUCTION

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is the most common clinical presentation of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). Two main FTD phenotypes are seen. One form is primarily a disorder of behavior and executive function (bvFTD), and the second, less frequent form is primarily a disorder of language, termed primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and defined by predominant language impairment for at least 2 years. Classifications of PPA include nonfluent/agrammatic (naPPA), semantic variant (svPPA), and logopenic variant (lvPPA). Combinations of behavioral and language symptoms that do not fit clearly into defined clinical subtypes reflect overlapping distributions of neuropathology in prefrontal and anterior temporal regions and can be present at disease onset but typically become more frequent with advancing disease severity.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Overall, FTD is the fourth most common dementia (behind Alzheimer disease [AD], vascular dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies), affecting 1% to 16% of all people with dementia; FTD is the most common cause of dementia prior to age 60 years and approaches the prevalence of AD prior to age 65 years. Approximately 60% of cases occur in individuals aged 45 to 64 years. Although we do not yet have definitive epidemiologic studies, the estimated point prevalence of FTD within this age range, based on studies primarily including Caucasians in North America and Europe, is 15 to 22/100,000. Most studies implicate an equal distribution by gender.

PATHOBIOLOGY

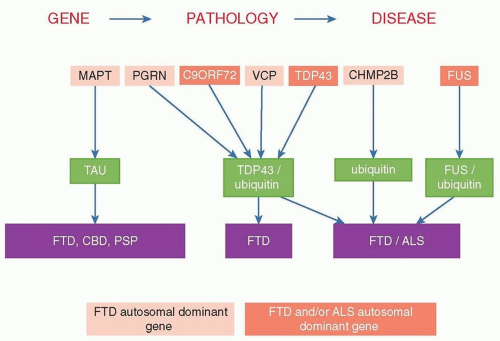

At autopsy, gross frontal and temporal lobe atrophy is usually evident, with histopathology revealing neuronal loss and gliosis affecting superficial cortical lamina of these same cortical regions, along with absence of the typical pathologic findings of AD. FTLD encompasses several different pathologies, including neuronal inclusions containing TAR DNA binding protein (TDP-43), tau isoforms, and fused in sarcoma (FUS) protein. Some patients have evidence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). As demonstrated in Figure 51.1, several gene mutations associated with FTD result in specific neuropathologies and sometimes specific clinical presentations. Therefore, for some patients, the clinician can infer the neuropathology based on some (e.g., FTD-ALS), but not other (e.g., behavioral variant FTD), clinical presentations.

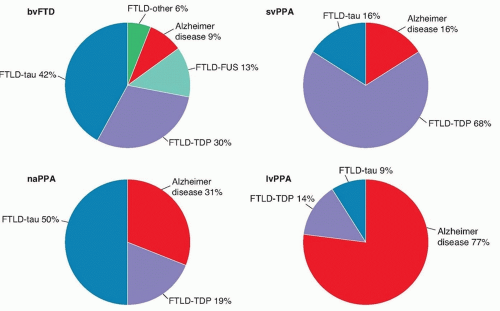

Only fewer than half of all FTD patients will demonstrate prominent tau aggregates, whereas approximately half will stain for ubiquitin, a nonspecific marker of cell death, although the breakdown of pathologies across subtypes differs (Fig. 51.2). A major FTLD subtype associated with tau aggregates is Pick disease. First described by Alois Alzheimer, Pick disease is characterized by argyrophilic cytoplasmic tau inclusions (Pick bodies) and swollen neurons (Pick cells). Ubiquitin-positive cases of FTLD were recently discovered to be characterized by inclusions composed

of aggregates of TDP-43 and more rarely FUS. The clinical presentation of FTD-ALS is associated with TDP-43 positive FTLD (see Fig. 51.1).

of aggregates of TDP-43 and more rarely FUS. The clinical presentation of FTD-ALS is associated with TDP-43 positive FTLD (see Fig. 51.1).

GENETICS

An estimated 40% of cases of FTLD are familial, but only 10% follow a clear autosomal dominant pattern. Mutations in three genes account for the great majority of cases of FTD with an identified genetic cause (see Fig. 51.1). The most common genetic cause of both FTD and ALS appears to be the recently identified hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 on chromosome 9. This expansion accounts for approximately 34% of familial ALS, 6% of sporadic ALS, 26% of familial FTD (with or without ALS), and 5% of sporadic FTD. The discovery of C9ORF72 links FTD and ALS with several other neurologic disorders involving repeat expansions including Huntington disease, fragile X syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, and some of the spinocerebellar ataxias. The phenotype associated with C9ORF72 expansions can be FTD, ALS, or combined FTD-ALS.

The two other known major genetic causes of FTD are mutations in the MAPT (tau) and GRN genes. Tau binds to microtubules, and it exists in isoforms of three and four microtubule-binding domains generated by alternate splicing of exon 10. Deposition of three-repeat tau is associated with Pick disease, whereas four-repeat tau is associated with CBD and PSP. GRN is an oncogene that codes for the protein granulin, which is a growth factor involved in wound healing. Reduced levels of granulin are associated with FTD, but elevated levels of granulin are associated with certain tumors including teratomas and breast, esophageal, and liver cancers. This is similar to another FTD/oncogene, FUS. Rare other genetic causes of FTD include mutations in valosin-containing protein, TDP-43, and CHMP2B. Clinical genetic testing can be considered with the guidance of a genetic counselor. Until recently, it was generally thought that an FTD patient should have a first-degree relative with FTD or a related illness to be offered clinical genetic testing. However, genetic testing of cases of FTD-ALS without a family history for C9ORF72 should be considered. Clinical presentation and pathology in family members can guide genetic testing and whether to test only for known mutations or to sequence the gene.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

BEHAVIORAL VARIANT

The ventral prefrontal cortex is usually involved in bvFTD and appears to play an important role in social cognition and behavior. Alteration in personality and behavior, reflecting impaired judgment of social norms, is a hallmark feature of bvFTD. Patients display a loss of social graces, generally characterized by decreased empathy, diminished reactions to emotional events, excessive familiarity with strangers or acquaintances, inappropriate jocularity, and a general lack of self-consciousness. Distractibility, impulsivity, and apathy are also components of bvFTD. Such symptoms may be subtle at onset. The apathetic and amotivational aspect of bvFTD may initially be mistaken for depressed mood; however, it is relatively rare for patients with bvFTD to endorse feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Patients may also present with stereotyped behaviors, involving movement, language, or more complex behaviors. Increased appetite and hyperphagia, particularly for

sweets, and hyperorality can also occur. Patients with bvFTD frequently demonstrate reduced awareness of or lack of concern for their symptoms.

sweets, and hyperorality can also occur. Patients with bvFTD frequently demonstrate reduced awareness of or lack of concern for their symptoms.

PRIMARY PROGRESSIVE APHASIA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree