General Aspects

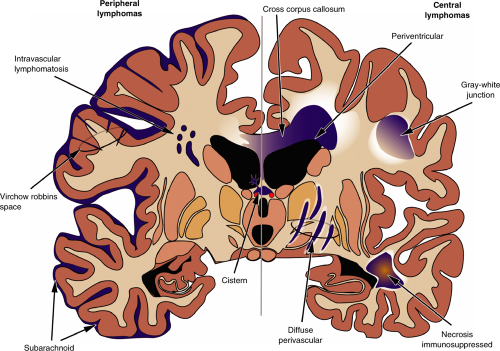

Two distinct categories of lymphoma affect the central nervous system: those that arise in the periphery and those that remain confined to the brain or spinal cord. Several types of peripheral lymphomas impinge on the brain, including high- and low-grade tumors as well as both T-cell and B-cell derived neoplasms. However, these lymphomas develop outside the brain, topologically exterior to the pial surface. They usually remain confined to the subarachnoid space, including the Virchow-Robbins space, unless the pial surface itself is injured. Brain invasion remains limited. A rare subset of lymphoma proliferates mainly within vascular spaces (intravascular lymphomatosis) but does not infiltrate the brain. In contrast, lymphomas that replicate predominantly within the brain compartment (primary central nervous system lymphoma [PCNSL]), beneath the pial surface, have the capacity to infiltrate into the surrounding parenchyma. Although they retain a perivascular predilection, they also invade brain tissue. These tumor cells express the enzymatic and structural machinery necessary to break down and travel within the brain’s extracellular matrix.

Primary brain lymphomas are more homogeneous than their peripheral counterparts: they are all high-grade and all derived from B-cells. In addition, instead of growing on the outside of the brain, they more frequently originate in the white matter or near the ventricular system (Table 9-1, Figure 9-1). Two populations of patients develop primary central nervous system lymphomas: the elderly and the immunocompromised. The latter group includes patients with AIDS and individuals with iatrogenically compromised immune systems, such as transplant patients.

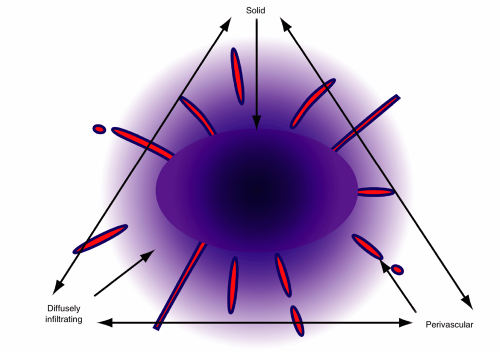

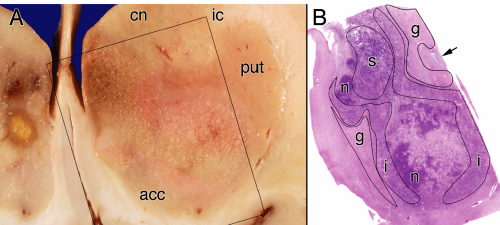

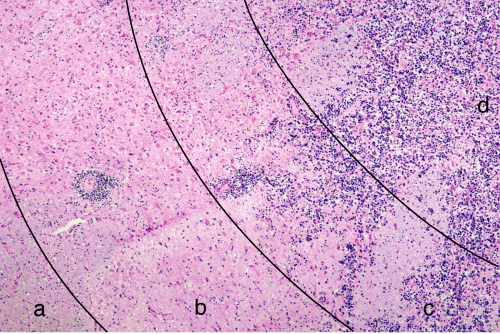

Central lymphomas grow in several patterns, including as a solid mass, as a widely infiltrating tumor, and in a predominantly perivascular pattern (Figure 9-2). Although one feature predominates in some tumors, most primary lymphomas show some combination of features (e.g., solid center, infiltrating edge). In a typical case, a tumor can have a central area seemingly solidly packed with tumor, an edge where tumor cells and some reactive lymphocytes infiltrate surrounding brain, a penumbra of reactive T-lymphocytes and astrocytes, and a border of gliosis (Figures 9-3 and 9-4). Nearly all PCNSLs contain a significant percentage of small, reactive T-lymphocytes. In some biopsies, these are a dominant feature, which occasionally leads to a misdiagnosis of a T-cell lymphoma. If small B-cells are present, they only represent a minor population of reactive cells. In normal reactive brain processes, T-cells predominate. When a primary lymphoma is inadvertently pretreated with steroids prior to biopsy, these T-cells may be the only remaining lymphocytic population. Chronic inflammatory mediators often injure myelin. When combined with the inevitable gliosis, the combination of small T-cells and the loss of myelin in a steroid-treated tumor become indistinguishable from demyelination.

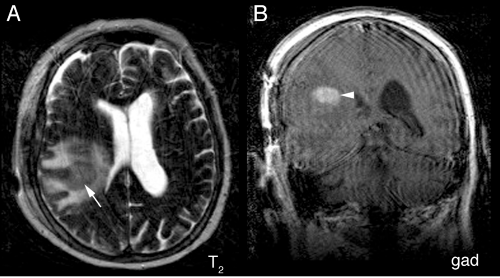

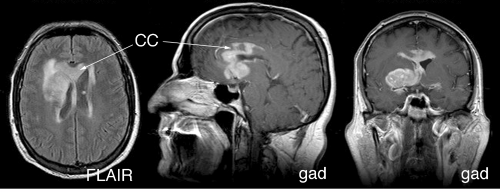

Neuroimaging supplies key information to the intraoperative pathologist: primary lymphomas are intrinsic, infiltrate brain, have a predilection for the periventricular region, and can be multifocal. Because the tumors lie beneath the pia, radiology will show them to be “intraaxial.” A central enhancing component usually represents the solid portion of the tumor, whereas an extended T2-bright rim results from either tumor infiltration or the surrounding edema it invokes. Solidly packed tumor, in which the dense cellularity displaces water, shows a decreased T2 signal centrally but an increase in their penumbra (Figure 9-5). Like primary gliomas and unlike metastases or most other tumors, primary lymphomas can travel along white matter tracts and cross the corpus callosum (Figures 9-6 and 9-7). They often present in two disparate regions of the brain, which is a feature they share with metastases and

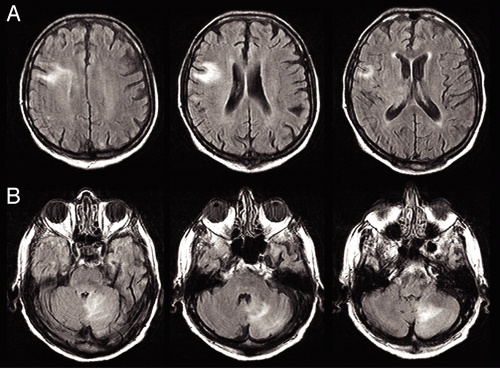

occasional gliomas. Unlike lymphomas, multiple metastases remain discrete with sharp borders of enhancement. Unlike most gliomas, which in older patients usually avoid the infratentorial nervous system, primary lymphomas diffusely infiltrate cerebral, cerebellar, and other white matter, including the spinal cord (Figure 9-8).

occasional gliomas. Unlike lymphomas, multiple metastases remain discrete with sharp borders of enhancement. Unlike most gliomas, which in older patients usually avoid the infratentorial nervous system, primary lymphomas diffusely infiltrate cerebral, cerebellar, and other white matter, including the spinal cord (Figure 9-8).

|

In some central lymphomas that have a perivascular predilection, the tumor fails to produce a central mass and may present more diffusely. Neuroimaging can demonstrate several separate areas of tumor (Figure 9-9).

Peripheral lymphomas and other hematopoietic tumors that secondarily affect the brain remain largely outside the pia. These most often affect the subarachnoid space (meningeal lymphomatosis), including the Virchow-Robbins region around vessels as they dive into brain. Although their growth is predominantly exterior to parenchyma, they can appear to invade brain by traveling deep into and expanding sulci, producing extensive brain edema that obscures the tumor-brain interface, and inducing necrosis of their tissue host.

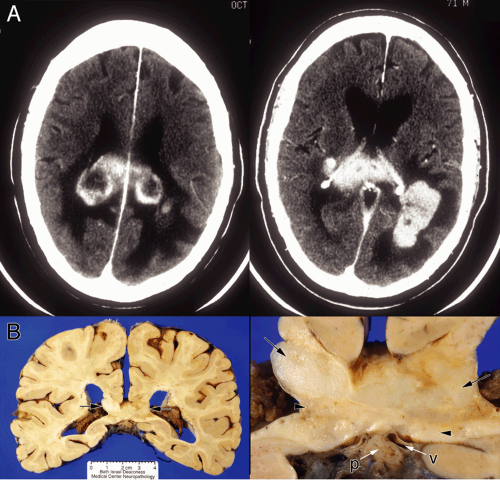

During development, the neural tube kinks at several locations and cellular proliferation balloons out masses of tissue in key spots. As the hemispheres greatly expand and fold backward, they envelop the previous dorsal surface of the brain, including the pineal and deep cerebral veins. The junction where these new hemispheric surfaces bury the old surface becomes the location where the choroid plexus forms. For this reason, some tumors of the meninges, including meningiomas and invading peripheral lymphomas, can occur along these junctions and in the choroid plexus (Figure 9-10).

Primary Lymphomas

An intraoperative smear provides key and unique information about a lymphoma. Several features distinguish these tumors (Figure 9-11):

Lymphomas are discohesive.

Lymphoma cells may be enmeshed in a glial network.

All lymphomas have a perivascular predilection, although extensive growth can efface this feature.

Although individually pleomorphic, the spectrum of intercellular variability remains smaller than in other high-grade nervous system tumors.

Primary brain lymphomas have high-grade nuclei with one or several nucleoli and scant cytoplasm.

FIGURE 9-8. Multicentric primary nervous system lymphoma FLAIR MRI. This tumor presented in two disparate locations, in the right frontal lobe and left cerebellum. A. FLAIR signal lies in the subcortical white matter, in the region of the cortical end-arteries. The cortex itself remains curiously spared. B. FLAIR signal extends from the fourth ventricle at the superior cerebellar peduncle (left) to the cerebellar gyral surfaces (middle). Individual folia stand out in this image, indicating probable subarachnoid tumor. The tumor has also diffusely infiltrated the deep cerebellar white matter (right). This diffuse pattern of multicentric growth can only be produced by one of two tumors: a primary lymphoma or a glioma. Given the presence of tumor in both cerebellar and cortical white matter, in an elderly patient, the diagnosis would most likely be a lymphoma. For the histology of this case, see Figure 9-16. |

By their very nature, cells from primary nervous system lymphomas do not adhere to each other; this structural feature is key when examining a smear. In the center of a solid mass of lymphoma, the cells spread out evenly during the smear preparation, which gives a smooth gradient of cells (Figure 9-12A

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree