Hemifacial Spasm

Paul Greene

INTRODUCTION

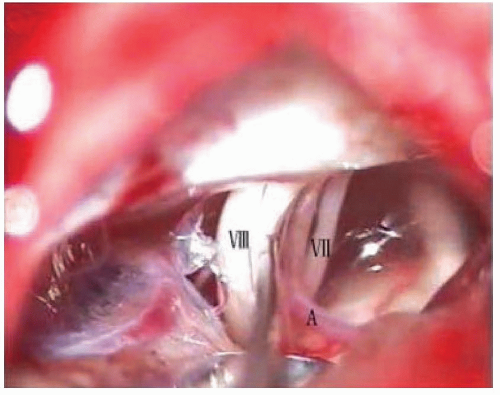

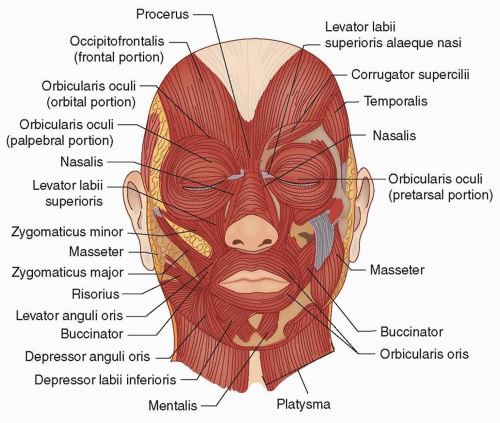

In hemifacial spasm (HFS) there are involuntary contractions on one side of the face in muscles innervated by the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) (Figs. 77.1 and 77.2). According to Digre and Corbett, the condition was first described in 1875 by Schultze but was first separated from other forms of facial twitching by Gowers in 1888. HFS is rare in this country. The age-adjusted incidence was 0.78 per 100,000 per year in Olmsted County, Minnesota, only 3% of the incidence of Bell palsy.

PHENOMENOLOGY

The contractions in HFS usually start as individual muscle twitches in the eyelids. Over time, twitches spread to other facial nerve-innervated muscles including the frontalis, paranasal muscles, zygomaticus major, perioral muscles, platysma, and occasionally, the periauricular muscles. Trains of twitches may develop and, when severe, there may be periods of sustained muscle contraction causing complete eye closure. Pain in HFS is very rare, usually from patients with concurrent involvement of the trigeminal nerve producing tic douloureux (the combination is called tic convulsive).

Contractions in HFS diminish, but do not disappear, during sleep and patients often report worsening with stress. This is surprising for what is usually presumed to be a peripheral nerve disease (see the following discussion). HFS usually progresses slowly if at all but may produce facial weakness in patients with long duration of disease. About 1% of reported cases of HFS are bilateral (with twitching that is asynchronous from side to side). The majority of cases of HFS are sporadic, although there are occasional reports of familial cases (Video 77.1).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are few other diseases that produce twitches, trains of twitches, and occasionally, episodes of sustained muscle contraction (Table 77.1). Facial dystonia is usually more sustained and bilateral and muscle contractions are not usually synchronous. The rippling movements of facial myokymia are often unilateral but are slow and asynchronous. Motor tics in the face may be unilateral and rapid, but there is usually a warning sensation before the movements and the movements are usually suppressible, at least briefly. Synkinesis after Bell palsy or other cause produces synchronous contractions but only during blinking or voluntary movement. However, some patients develop HFS in addition to a synkinesis after nerve injury. Epilepsia partialis continua does mimic the movements of HFS precisely but usually involves the masseters (cranial nerve VII) and is rarely limited to the face.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of HFS is thought to be compression of the facial nerve where it exits the brain stem (the root exit zone), usually by an aberrant artery, such as the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, posterior inferior cerebellar artery, or internal auditory artery, or a normal vein. Irritation of the nerve at this site is felt to generate spontaneous electrical activity, causing muscle contractions, and “cross-talk” or simultaneous activation of axons going to different parts of the face. However, other causes of compression at the root exit zone besides normal arteries rarely occur, such as draining veins of arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), aneurysms, tumors, or plaques of multiple sclerosis in the central myelin at the root

exit zone of the facial nerve. For this reason, all patients with HFS should have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with attention to the posterior fossa. If compression by aberrant arteries is the most common cause for HFS, it would be reasonable that arterial hypertension causing ectatic vessels might be a risk factor for HFS. Older studies suggested this, but recent carefully controlled studies failed to find such an association.

exit zone of the facial nerve. For this reason, all patients with HFS should have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with attention to the posterior fossa. If compression by aberrant arteries is the most common cause for HFS, it would be reasonable that arterial hypertension causing ectatic vessels might be a risk factor for HFS. Older studies suggested this, but recent carefully controlled studies failed to find such an association.

Occasionally, HFS has been seen after Bell palsy, bony overgrowth as in Paget disease pinching the stylomastoid foramen, and other peripheral lesions of the facial nerve. This has led to speculation that facial nerve compression induces a change in the facial nucleus, which is necessary for HFS to occur. The likelihood of such a facial nucleus change would increase as the site of compression gets closer to the nucleus. This alternative hypothesis is strengthened by the small number of cases of HFS associated with central lesions at the site of the facial nerve nucleus. In addition, there is evidence in HFS suggesting hyperexcitability of the facial nerve nucleus, including enhancement of F waves and other findings.

TABLE 77.1 Differrentiial Diagnosis of Hemifacial Spasm

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|