and Robert E. Schmidt2

(1)

Sunnybrook and St Michael’s Hospitals, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

(2)

Division of Neuropathology Department of Pathology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA

10.1 Sarcoidosis

10.1.1 Clinical Manifestations

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease characterized by formation of noncaseating granulomata in many tissues and organs with a predilection for African Americans, Europeans, and, especially, Swedes. Neurological symptoms occur in about 5 % of patients (Delaney 1977) and may be the only manifestation of disease (Chapelon et al. 1990). Any part of the nervous system may be involved, but the single most common clinical feature is a peripheral seventh cranial nerve palsy, seen in about a third of patients with neurosarcoidosis (Delaney 1977; Chapelon et al. 1990; Oksanen 1986). Non-cranial neuropathy occurs in 15–40 % of patients (Delaney 1977; Chapelon et al. 1990; Oksanen 1986) and may exist in the absence of any other symptoms, neurological or systemic (Chapelon et al. 1990). Subclinical neuropathy is even more common (Challenor et al. 1984). Although the older literature emphasizes mononeuritis multiplex, a relatively mild chronic progressive distal polyneuropathy is more common (Chapelon et al. 1990; Zuniga et al. 1991) and was the syndrome seen in nearly every pathologically verified case to date, even those with vascular changes (vide infra). Mononeuropathy may occur (Chapelon et al. 1990), and a Guillain–Barré-like picture has been very rarely reported in association with sarcoidosis (Chapelon et al. 1990; Oksanen 1986; Miller et al. 1989) (Case 10.1). Electrophysiological testing is usually most consistent with axonal neuropathy, either distal symmetrical or multifocal (Challenor et al. 1984; Zuniga et al. 1991), but slowed conduction suggesting demyelination has been reported (Chapelon et al. 1990; Galassi et al. 1984). CSF examination may show increased protein, pleocytosis, or low glucose.

10.1.2 Pathology

10.1.2.1 Role of Nerve Biopsy

Peripheral nerve pathology in sarcoidosis has only rarely been reported, as most often the systemic diagnosis is already known, or diagnosis is obtained from another tissue in a patient with polyneuropathy. Thus, it is impossible to determine the sensitivity of nerve biopsy for the diagnosis. In one autopsy study that explored several peripheral nerves, there were only sparse inflammatory infiltrates without granulomata despite marked axonal loss (Zuniga et al. 1991). In one case we have examined, an initial nerve biopsy was diagnostic, but at autopsy 5 years later, no disease was found in any of the five peripheral nerves studied, even though the disease was disseminated in other tissues. Muscle biopsy may be positive in as many as 50 % of patients without clinical evidence of muscle disease (Stern et al. 1985). Thus, if nerve biopsy is being considered, a muscle specimen should be taken as well since tuberculoid leprosy, often in the differential diagnosis, does not involve the muscle. The discussion below is based on review of 11 adequately described cases in the literature (Brochet et al. 1988; Ide et al. 1984; Gainsborough et al. 1991; Galassi et al. 1984; Krendel and Costigan 1992; Nemni et al. 1981; Oh 1980; Vital et al. 1982; Yakane et al. 1986) and personal experience with two cases (vide infra). Krendel and Costigan (1994) also described a case with granulomatous perineuritis, cutaneous anergy, and abnormal lung diffusing capacity that very likely had sarcoidosis.

10.1.2.2 Light Microscopy

The sarcoid granuloma is a compact mass of epithelioid cells derived from macrophages which reflect the development of secretory and bactericidal capability and loss of some phagocytic capability. With time, fibroblasts appear and perilesional fibrosis develops. The number of lymphocytes surrounding the granuloma varies from moderate (Fig. 10.1a, b) to none (“naked” granuloma) (Fig. 10.2). T-cell lymphocytes may be markedly increased in areas of active granulomatous disease, with an increased ratio of T-helper cells to T-suppressor cells (Said 2013). A Th1-type T-cell response with secretion of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, and IL-12 is thought to favor the granulomatous response at sites of disease activity (Kataria and Holter 1997). Infrequently plasma cells and eosinophils are seen in the periphery. A cytological evolution from macrophages to epithelioid cells can be seen, and epithelioid cells may fuse into multinucleate giant cells (Soler and Bassett 1976). However, the latter are only rarely seen in the peripheral nerve. Caseation is not present.

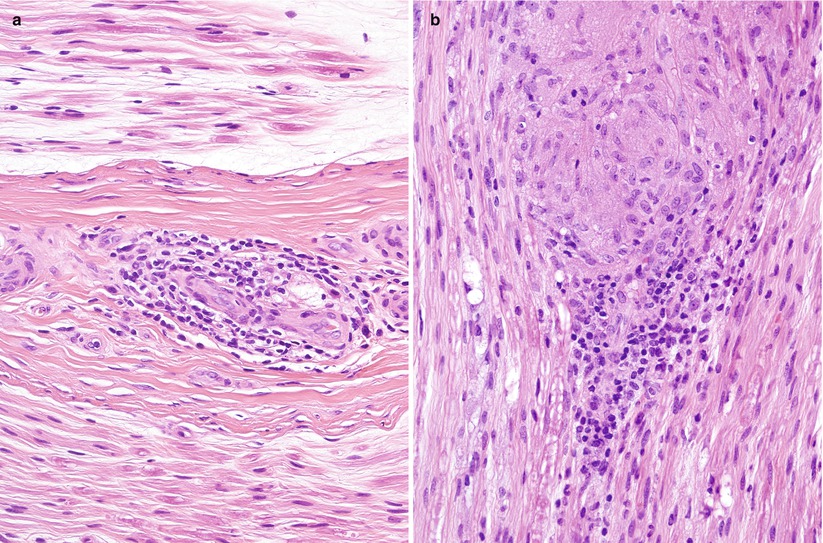

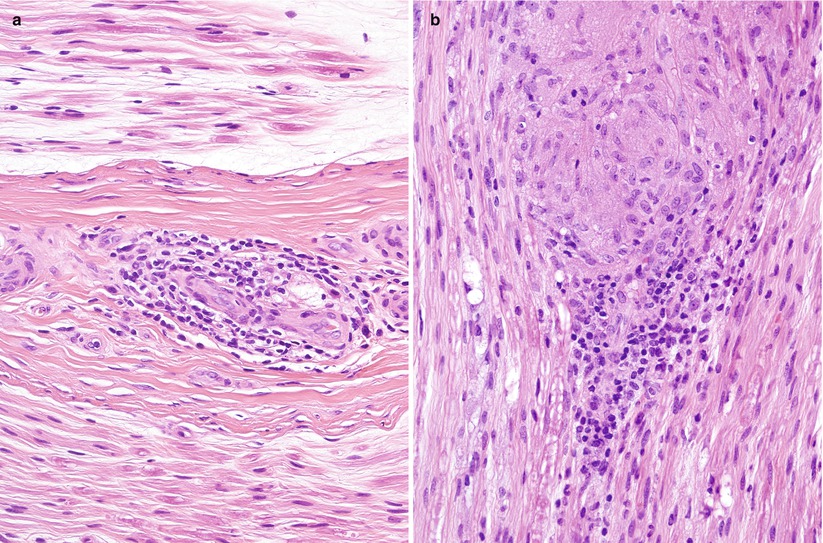

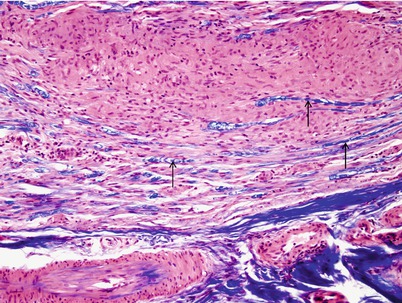

Fig. 10.1

Sarcoidosis: Sural nerve shows nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic collars (a) and organized epithelioid cell granuloma (b) (paraffin, H&E, 400×)

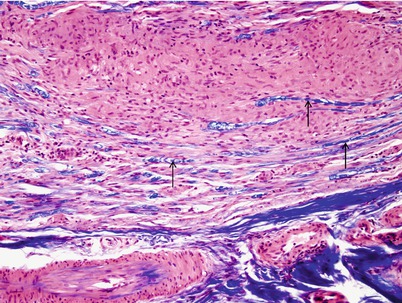

Fig. 10.2

Sarcoidosis: A typical “naked” granuloma is seen in the perivascular space of the epineurium. Multinucleated giant cells are not common in neural sarcoidosis (paraffin, H&E, 400×)

Granulomata may be found in the endoneurium or epineurium (Figs. 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, and 10.4). Vascular involvement ranges from complete sparing (Nemni et al. 1981) through periangiitis (Galassi et al. 1984; Ide et al. 1984; Yakane et al. 1986) to true vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis and luminal occlusion (Vital et al. 1982; Said et al. 2002). Lymphocytic cuffing can be present in the absence of granulomata (Fig. 10.1a). Infiltration of the perineurium by epithelioid histiocytes (Fig. 10.4a) may be so prominent as to be reminiscent of leprosy or idiopathic perineuritis (Brochet et al. 1988; Krendel and Costigan 1994; Oh 1980).

Fig. 10.3

Sarcoidosis: Note displaced MF-stained blue with LFB–H&E (arrows) adjacent to an epithelioid cell granuloma (paraffin, 400×)

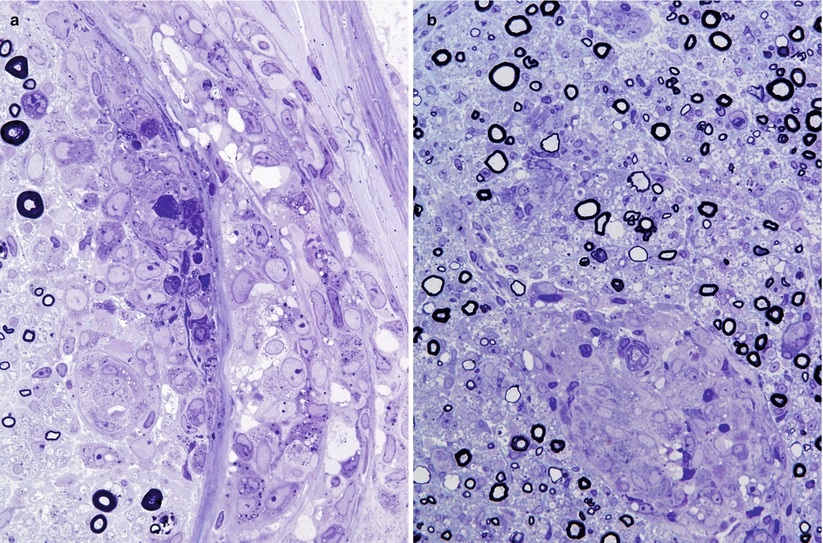

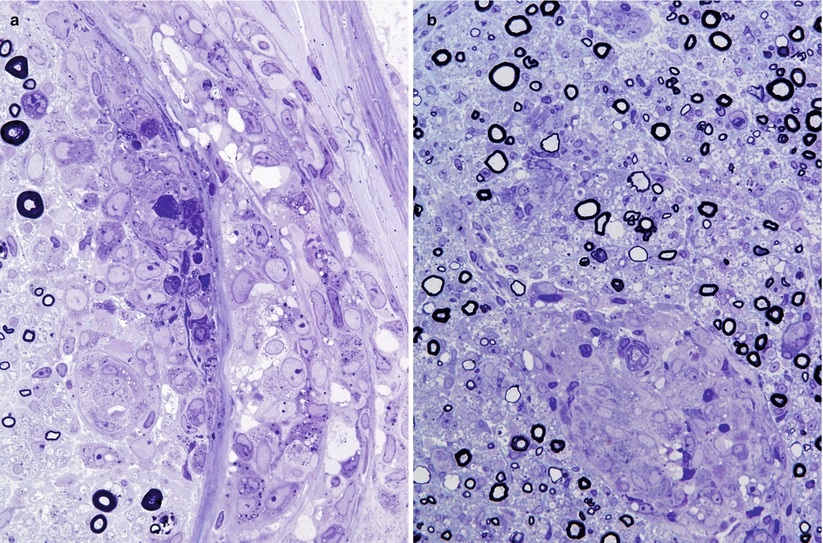

Fig. 10.4

Sarcoidosis: Focal lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltrate in the perineurium (a) may accompany endoneurial epithelioid cell granulomata (b). Many of the MFs surrounding the granuloma have attenuated myelin sheaths (1 μ thick toluidine-stained plastic sections, a, b: 600×)

Axonal loss of variable severity predominates and may be multifocal or diffuse or very active or chronic. Regenerating clusters may be seen. Unmyelinated fibers can be relatively spared. Segmental demyelination and remyelination may occur, and in our material this seemed to be most prominent immediately adjacent to the endoneurial granulomata (Fig. 10.5). Some teased fiber studies have demonstrated a pattern consistent with primary demyelination (Nemni et al. 1981), but others showed only axonal damage (Oh 1980) or secondary demyelination (Gainsborough et al. 1991).

Fig. 10.5

Sarcoidosis: Nerve fibers adjacent to granuloma show accumulation of neurofilaments (arrowhead) and segmental demyelination (arrow) (4,160×)

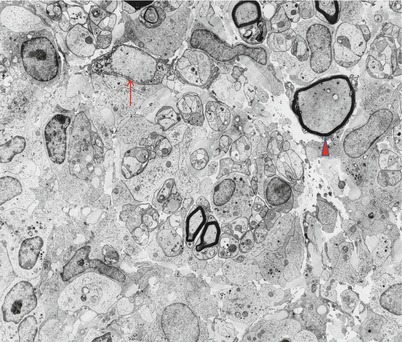

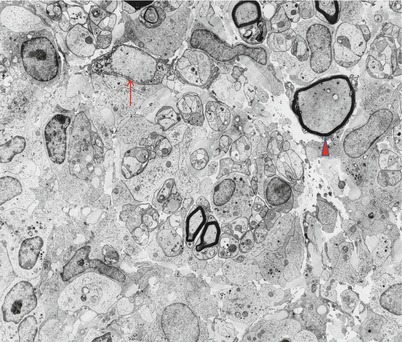

10.1.2.3 Electron Microscopy

Epithelioid histiocytes are large elongated cells with long processes that interdigitate with those of adjacent cells (Fig. 10.5). Boundaries between adjacent cells may become indistinct. Nuclei are irregular and convoluted and display prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm contains numerous mitochondria, active Golgi complexes, and accumulations of RER. Small single membrane-bound vesicles can be abundant, sometimes containing an ill-defined granular material. Non-epithelioid macrophages are distinguished by the presence of lysosomes and relatively few long cellular processes. Nerve fibers in the vicinity of granulomata may appear distorted (Gainsborough et al. 1991), and in one of our cases, axons immediately adjacent to the granuloma showed filamentous accumulations and swelling, reminiscent of “giant axonal” change (Fig. 10.5).

10.1.3 Pathogenesis

The lesion in sarcoid neuropathy is predominantly axonal. Because some biopsies have demonstrated marked distortion of nerve fibers by endoneurial granulomata, with no evidence of vascular damage or ischemia, a role for local peri-inflammatory injury has been postulated. Indeed, histiocytes secrete cytotoxic substances that might have local effects (Said and Hontebeyrie-Joskowicz 1992; Selmaj and Raine 1988). Precisely, such a pattern was observed in our material, with axonal swelling and filament accumulations seen only immediately adjacent to the granulomata. In such a manner, multiple random small endoneurial lesions might summate to produce a distally predominant polyneuropathy (Waxman et al. 1976). Conversely, those authors who have observed vascular lesions (Ide et al. 1984; Oh 1980; Vital et al. 1982) favor an ischemic pathogenesis, which would fit the mononeuritis multiplex pattern sometimes seen in sarcoidosis. The involvement of nerve roots and dorsal root ganglia must also be considered (Camp and Grierson 1962; James and Sharma 1967; Manz 1983).

No histology is available for the rare reports of a Guillain–Barré-like syndrome in association with sarcoidosis (Oksanen 1986; Miller et al. 1989). Some of the cases reported as GBS were clinically atypical (Strickland and Moser 1967). This may be a chance association (Miller et al. 1989), despite Oksanen’s observation (1986) that GBS developed coincident with activation of systemic sarcoidosis in two patients. Case 10.1 reported below initially presented as GBS, but the subsequent clinical course was not typical of the syndrome.

10.1.4 Differential Diagnosis

Sarcoidosis is not a diagnosis that can be made on peripheral nerve biopsy alone, because the disease is defined as “a multisystem granulomatous disorder of unknown etiology…supported by histological evidence of widespread non-caseating epithelioid cell granulomas in more than one organ…” (James et al. 1976). Even so, the presence of granulomata in a nerve biopsy almost always indicates a systemic disease, the exception being primary neuritic leprosy. Interestingly, in Case 10.1 described below, no evidence of sarcoidosis was found, and most reported cases of peripheral nerve sarcoidosis have had normal chest X-rays and minimal evidence of a systemic disease (Krendel and Costigan 1994). As no organisms are likely to be demonstrable in tuberculoid lesions of leprosy, clinical information becomes essential. In idiopathic perineuritis (vide infra), inflammation and epithelioid cell infiltration are largely confined to the perineurium, but the distinction from sarcoidosis may be difficult (Krendel and Costigan 1994).

Infiltration and even destruction of vessels by epithelioid cells may occur in sarcoidosis. This picture can also be seen in Wegener granulomatosis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, Churg–Strauss angiitis, polyarteritis nodosa, and giant cell arteritis. Angiocentric neurolymphomatosis should also be considered. The cytology and immunophenotype of the infiltrating cells will assist in the identification of the various entities. Eosinophils are not reliable indicators of the likelihood of Churg–Strauss angiitis.

Case 10.1

A 65-year-old woman had been experiencing GI upset with nausea and abdominal pain for 3 months preceding neurological presentation. Numerous investigations including endoscopy revealed no cause. Following onset with symmetrical paresthesias, the patient progressed over about 2–3 weeks to symmetrical moderate bilateral leg weakness and mild distal leg sensory loss to all modalities. There was no significant history of toxic exposure or travel. Reflexes were diminished and ankle jerks absent. Nerve conduction studies demonstrated a symmetrical axonal polyneuropathy, with minimal fibrillation in distal muscles. CSF examination was normal. The only abnormalities on further investigation were an ESR of 39 (Westergren) and ANA of 1:320. Renal, liver, and thyroid indices were normal. CBC, immunoelectrophoresis, serum calcium, serum ACE, porphyria screen, chest X-ray, pulmonary function tests, and abdominal ultrasound were normal. Nerve biopsy was performed 2 months after the onset of symptoms (Figs. 10.1, 10.2, and 10.3).

Following nerve biopsy, prednisone was initiated but was not tolerated by the patient. The severity of the patient’s illness remained unchanged. Prednisone was initiated again 6 months after onset, and over the subsequent year, there was gradual improvement with complete resolution of weakness and most sensory signs. Painful paresthesias became the major management issue. At several months since cessation of steroid therapy, there was no worsening (clinical material courtesy of Dr. C. Zahn).

10.2 Idiopathic Perineuritis

10.2.1 Clinical Manifestations

Idiopathic perineuritis was described in 1972 (Asbury et al. 1972) and remains an uncommon entity (Bourque et al. 1985; Matthews and Squier 1988; Logigian et al. 1993; Simmons et al. 1992; Younger and Quan 1994). Patients present with prominent sensory findings, including paresthesias, pain, and hypersensitivity to touch over affected nerves. Reports have emphasized the sensory involvement, but motor abnormalities are usually present. The condition evolves over weeks to months and may mimic mononeuritis multiplex (Logigian et al. 1993; Simmons et al. 1992), distal sensorimotor neuropathy (Bourque et al. 1985) (Case 10.2), or CIDP (Chad et al. 1986) both clinically and electrophysiologically. By definition, no identifiable disease is present, although nonspecific systemic symptoms may be seen. Improvement with steroid use or plasmapheresis has been reported anecdotally (Bourque et al. 1985; Logigian et al. 1993; Simmons et al. 1992).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree