and Colin L. W. Driscoll2

(1)

Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

(2)

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Mayo Medical School, Rochester, MN, USA

Postauricular Approach to the Infratemporal Fossa

Concept

Classically, this approach traverses the mastoid to reach the jugular foramen (termed a Fisch type A). It can be extended to reach the internal carotid artery, clivus, upper parapharyngeal space, and nasopharynx (Fisch types B, C, and D).

There are several different options for handling the facial nerve. These include

Leaving the nerve in place covered in a thin sleeve of bone (the fallopian bridge technique)

Rerouting the nerve in the lower half of the vertical segment just over the bulb (micro rerouting)

Rerouting the entire vertical segment from the second genu (short rerouting)

Rerouting the horizontal and vertical segments (long rerouting)

While the fallopian bridge technique causes no change in facial function, rerouting can create facial paralysis. The degree of facial paresis increases as more of the nerve is rerouted. With a long rerouting, complete facial paralysis in the immediate postoperative period should be expected. This will usually partially recover to reach a House–Brackmann grade III-IV functional level.

The postauricular infratemporal fossa approach can be tailored to provide as much exposure as needed to remove the tumor. These additional steps include

Removal of the ear canal with closure of the meatus

Translabyrinthine/transcochlear removal of the otic capsule

Decompression of carotid artery

Division of the GSPN followed by complete facial nerve rerouting (from the internal auditory canal to the stylomastoid foramen)

If the tumor extends through the dura of the jugular foramen, the procedure can be extended into a transjugular craniotomy. In this case, the sigmoid sinus is resected and the posterior fossa dura opened.

Conditions treated

Glomus jugulare

Jugular foramen schwannoma

Jugular foramen meningioma

Other tumors involving the jugular foramen and lateral skull base

Risks

Hearing loss

Facial nerve injury

Palsy of CN IX, X, XI, or XII

Injury to the internal carotid artery

Cerebral venous infarction or intracranial hypertension

Benefits

There is excellent exposure of the entire course of the sigmoid sinus, jugular bulb, and internal jugular vein.

Exposure of the internal carotid artery at skull base and into the petrous temporal bone.

CN VII, IX, X, XI, and XII can be traced all the way from the skull out into the face and neck.

1.

Diagram of the venous outflow of the brain. Note the multiple intra- and extracranial anastomostic pathways between the cavernous sinus and the jugular vein.

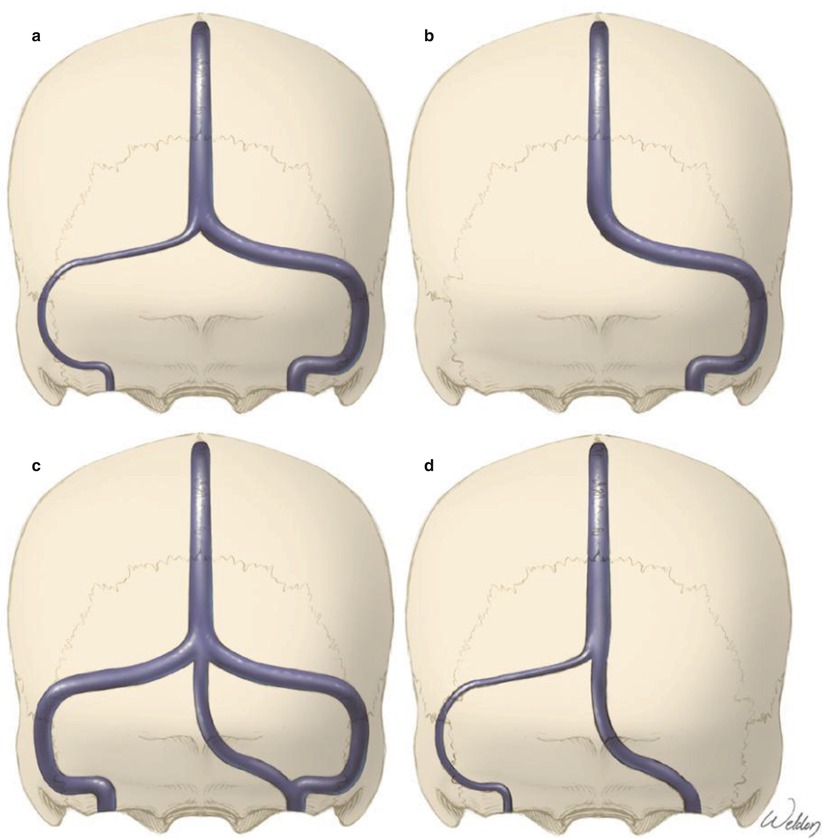

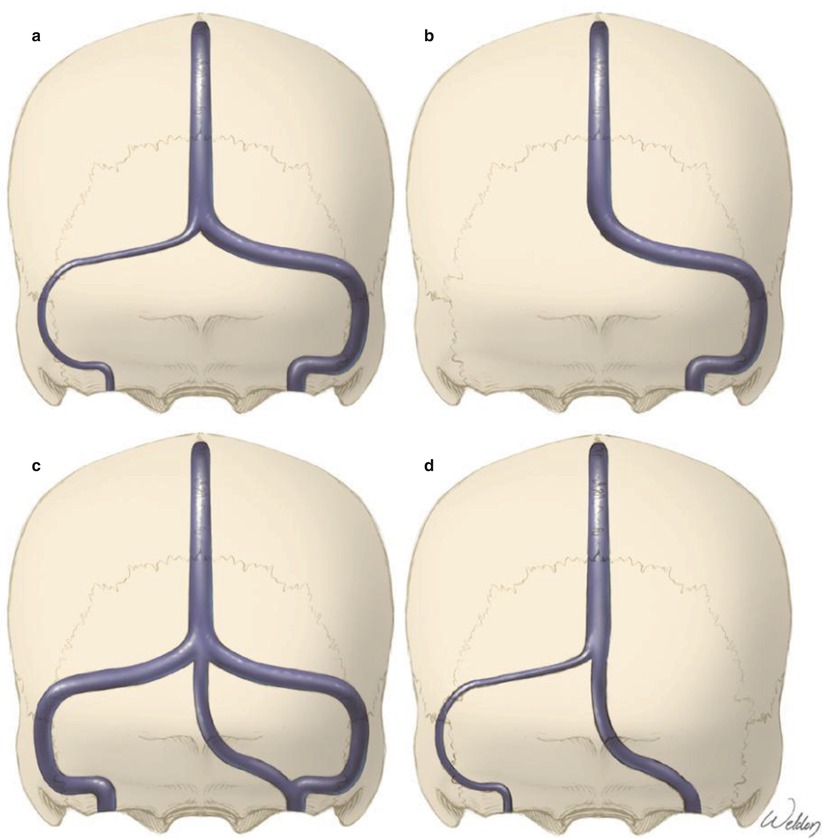

2.

There are also many congenital variants in the anatomy of the sigmoid sinus. (A) Most common is that one side is dominant. (B) Rarely, one side may be absent (C, D). Other anatomic variations are also occasionally found. Surgical planning should take this into consideration. For example, one would not want to resect a sigmoid sinus unless the sigmoid sinus on the other side is present and large enough to be able to handle the additional blood flow.

In otolaryngology residency training and in the clinical practice of general otolaryngology, little attention is paid to preservation of venous structures because of the robust collateral flow throughout the head and neck. It is even possible to remove both jugular veins with a relatively low risk of complications due to inadequate venous drainage. This is clearly a different environment than what we face within the skull base and intracranially. Cerebral venous infarction can be devastating, and even transient increased intracranial pressure can result in a CSF leak, pseudomeningocele, or need for a shunting procedure. It is critical to carefully assess venous flow prior to intervention. We often obtain an angiogram during the evaluation (assess tumor vascularity, status of carotid) and treatment (embolization) of these tumors, and this provides an opportunity to assess venous drainage. This is complementary to the MR venogram or CT angiogram. We may alter our surgical approach or aggressiveness of tumor removal based on venous drainage patterns. In vestibular schwannoma surgery, we will avoid a translabyrinthine approach when compromise of the sigmoid sinus could be catastrophic. Even without injury, the sinus can occlude after a translabyrinthine approach. Some tumors involving the jugular foramen that have partially or completely compressed the sigmoid sinus or jugular bulb/vein can be removed with preservation of the vein so even in cases with no flow through the vein, we may attempt to preserve the vein.

3.

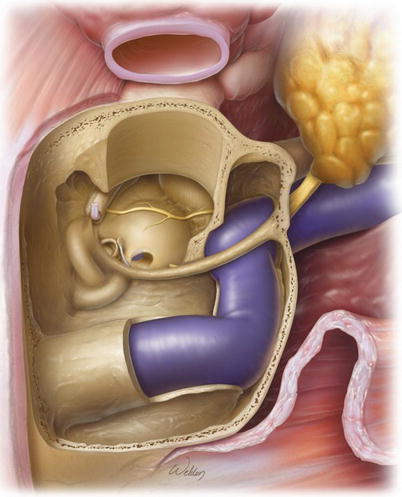

The postauricular approach involves resecting much of the bone within the dotted lines in order to expose the jugular bulb.

4.

The incision should be carried down onto the neck to allow for exposure and control of the jugular vein and carotid artery. When planning to open dura, it is possible that CSF may leak down into the neck postoperatively and form a pseudomeningocele. Therefore, it is best to limit the dissection in the neck to minimize the potential space for fluid to collect.

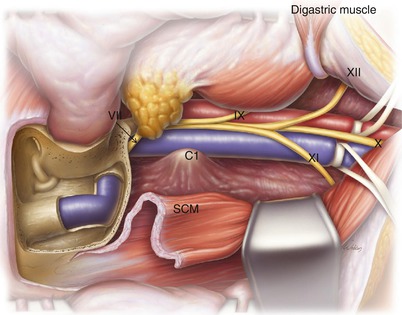

5.

The soft tissues are reflected off the mastoid and the parotid gland identified. Dissection is carried along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the digastric muscle identified. Deep and inferior to the digastric, the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein are identified. Rubber slings are wrapped circumferentially around the vessels with the ends held together with a hemostat. The slings should be kept loose so as not to compress the vessels. However in an emergency (i.e., rupture of the vessel), the slings can be pulled tight to control the bleeding. The vessel loops can also be placed around the artery and vein without circumferential looping. This still permits the surgeon a way to quickly pull up and clamp the vessel if needed. While perhaps not as secure as circumferential looping, there is less risk of traction on the loop causing inadvertent tightening around the vessel during the procedure.

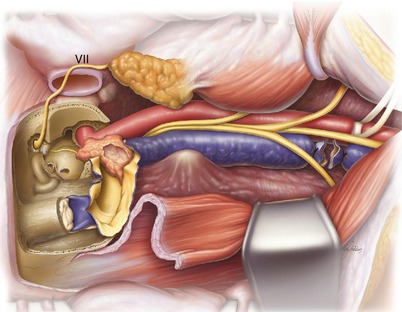

6.

A standard mastoidectomy has been performed and the ear canal wall preserved. The bone covering the inferior half of the sigmoid sinus has been removed (see the translabyrinthine approach for details on this technique). The facial nerve is identified at the second genu and followed down to the stylomastoid foramen. The main trunk of the extracranial facial nerve is identified but does not need to be dissected out to the pes anserinus.

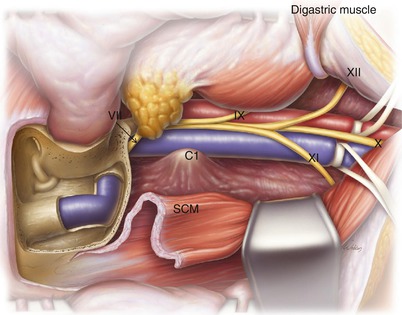

The key point of this entire operation is to expose the tissues inferior to the sigmoid sinus. This is performed by first releasing the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) from its attachment to the mastoid process, retracting it posteriorly and then drilling away the entire mastoid tip. Next, the digastric muscle is divided near its attachment to the skull base and retracted anteriorly. The bone inferior to the sigmoid sinus (the area of the digastric muscle attachment) is drilled away. Sometimes, a condylar emissary vein is found draining into the sigmoid sinus. This should be divided and occluded at this stage as it will decrease bleeding later during tumor removal in the jugular bulb region.

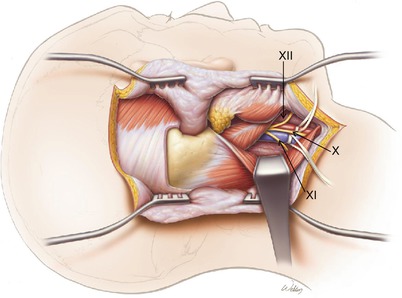

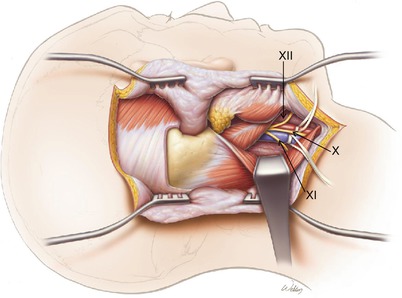

Removing these muscles and the bone that they attach to permits the great vessels to then be followed up to the skull base. CN IX, X, XI, and XII should all be identified during this dissection. The vertebral artery lies within the fascia along the posterior surface of the transverse process of C1; there is no need to enter this area.

7.

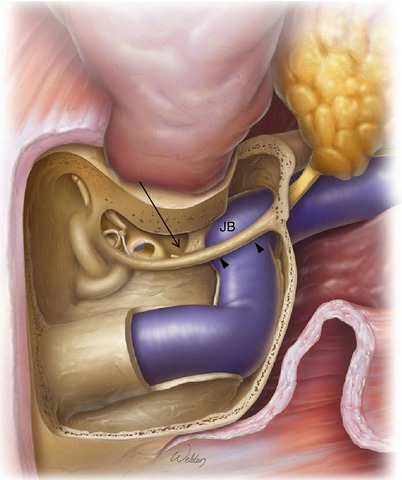

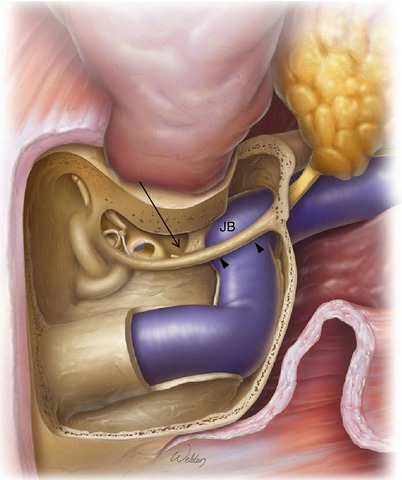

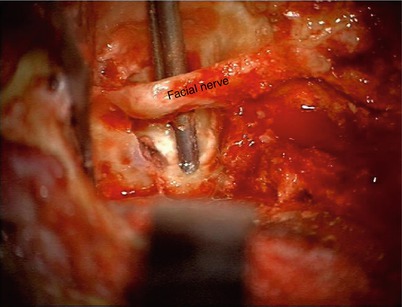

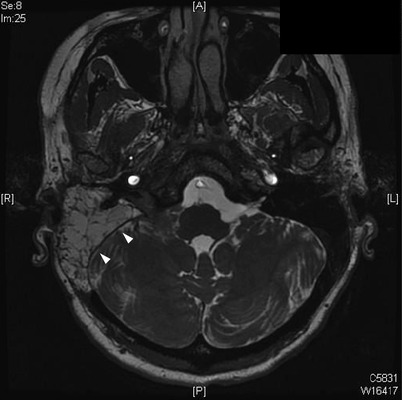

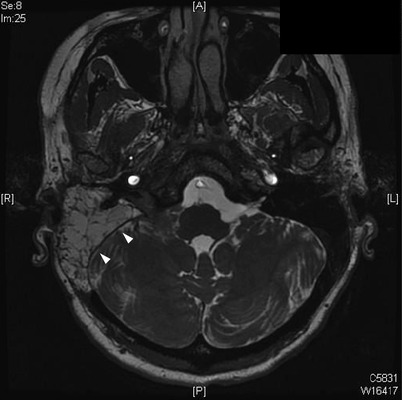

In this example, a canal wall up procedure with the fallopian bridge technique is shown. A facial recess approach is performed and then extended inferiorly. Dividing the chorda tympani nerve should be done sharply rather than with the drill to prevent traction injury to the facial nerve. Note that the ossicular chain should be left intact to maintain hearing with this approach.

The facial nerve is skeletonized circumferentially (arrowheads) to expose the jugular bulb (JB), which lies medial to it. However, a thin layer of bone should be left around the nerve to prevent injury. During this drilling process, the hypotympanum is widely opened (arrow). This permits removal of tumor that may have grown superiorly from the jugular foramen to enter the middle ear.

8.

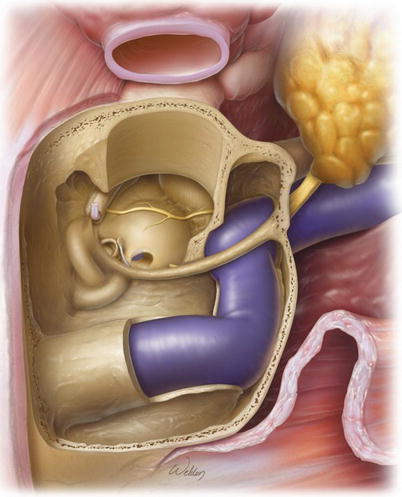

Alternatively, a canal wall down procedure can be performed as shown in this example. The ear canal is transected at the bony cartilaginous junction and most of the ear canal drilled away. Only the anterior canal wall is left intact. In order to remove the tympanic membrane, the incudostapedial joint is separated and the incus removed. Cutting the tensor tympani tendon then permits removal of the entire tympanic membrane and malleus. All ear canal skin is carefully removed using a round knife. Finally, the anterior ear canal bone is drilled smooth to verify that all epithelial remnants within it have been removed. Closure of this wound involves plugging the Eustachian tube, closing off the ear canal, and filling the defect with a fat graft (see the section on temporal bone resection in Chap. 8 for details). In this example, the fallopian bridge technique is still used. Alternatively, rerouting of the facial nerve may be performed to more completely expose the jugular bulb. To do this, the bone overlying the nerve should be carefully removed and the nerve elevated out of the fallopian canal (see Chap. 9 for details).

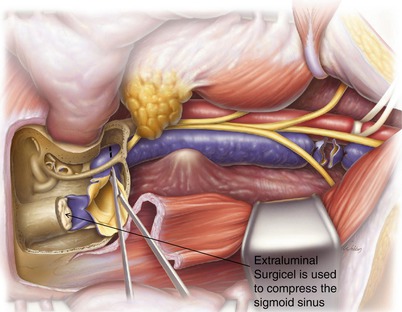

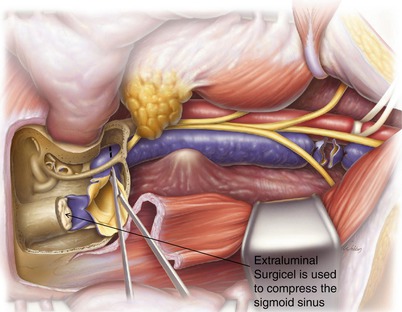

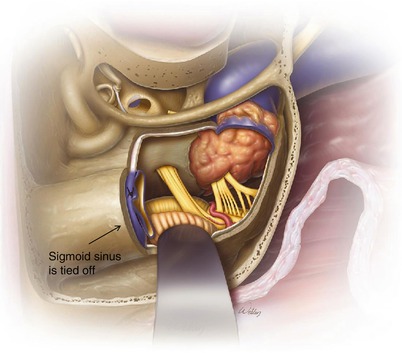

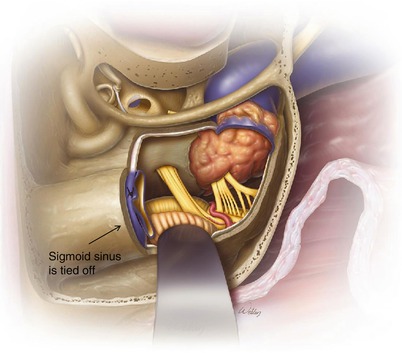

9.

Venous flow through the sigmoid sinus is blocked by extraluminal packing of Surgicel between the bone and the lateral sinus wall. Next, the internal jugular vein is divided and ligated in the neck.

The sinus can then be opened with a scissors to expose the jugular bulb. If there is a large tumor within the jugular bulb, bleeding is usually minimal at this stage. If there is only a small tumor or it is not fully occluding the bulb, bleeding from the condylar emissary vein and the inferior petrosal sinus can be significant. This bleeding can be partially controlled with Surgicel, cottonoid pledgets, and pressure. However, there is no way to completely stop this bleeding without full exposure of the bulb, removal of all tumor within it, and then packing of the bulb with Surgicel to occlude the inferior petrosal sinus collaterals and the condylar emissary vein. Care should be taken to not pack too tightly and risk injury to the underlying lower cranial nerves.

An alternative to extraluminal compression of the vein is to use a 6-0 nylon suture to sew across the vein tacking the anterior wall of the sinus to the posterior wall. While theoretically this can be done without opening the dura, it is significantly easier to do with opening of the dura. However, we would only do this if we were already planning to open the dura for tumor removal. The benefit of this method is that when opening the dura across the sigmoid sinus, it can be tough to get adequate pressure from extraluminal surgical packing. Also, it allows us to block the vein more distally, which may decrease the risk of occluding the superior petrosal sinus or vein of Labbé.

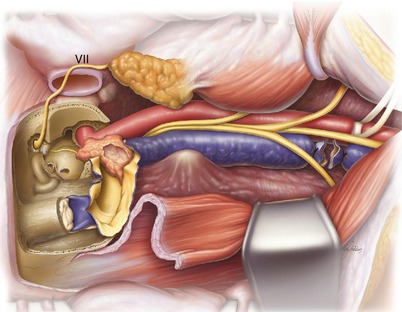

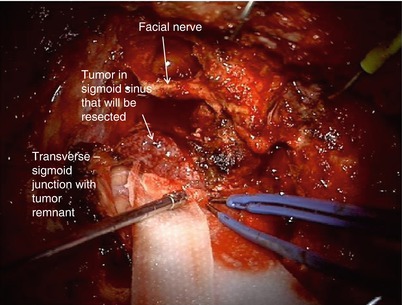

10.

In this example, a canal wall down technique has been used together with long rerouting of the facial nerve. The internal carotid artery has been exposed to the petrous temporal bone, and tumor within the opened jugular bulb is visible. The tumor is adjacent to the genu of the internal carotid artery. This tumor can now be carefully microdissected off the carotid artery and removed from the jugular bulb. There are often small branches emanating from the carotid artery at the genu, and this portion of the artery seems particularly vulnerable to injury. It is sometimes wise to leave a small amount of adherent tumor in this area.

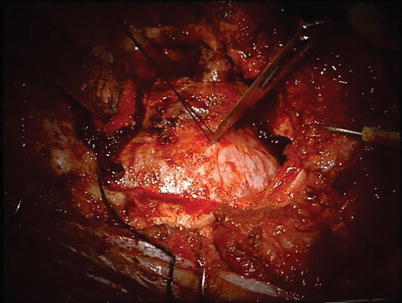

11.

If the tumor extends into the intradural space, a transjugular craniotomy can be performed. Rather than simply compressing the sigmoid sinus, it can be suture ligated and the dura across the sigmoid opened. This allows resection of intra- and extradural tumor. Watertight closure of the dura is needed if the canal wall up approach is used as shown here in order to prevent cerebrospinal fluid leak into the middle ear and down the Eustachian tube. Typically, we use an artificial dural patch, a dura sealant, and then pack off the mastoid with a fat graft. A lumbar subarachnoid drain is often beneficial as well for larger dural defects.

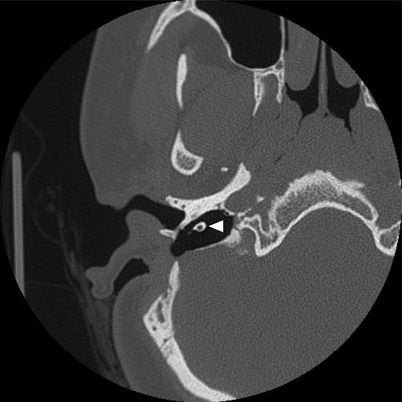

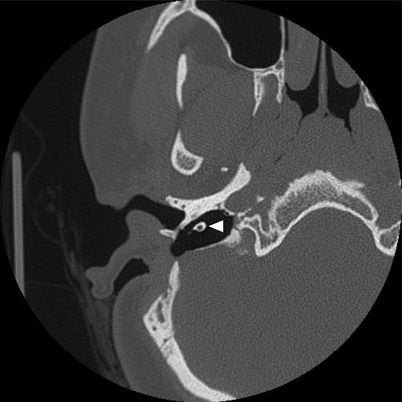

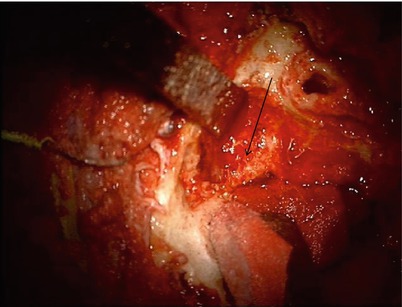

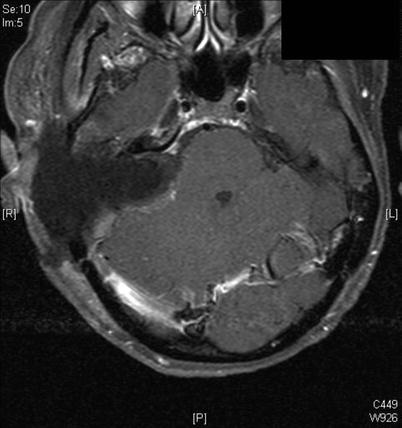

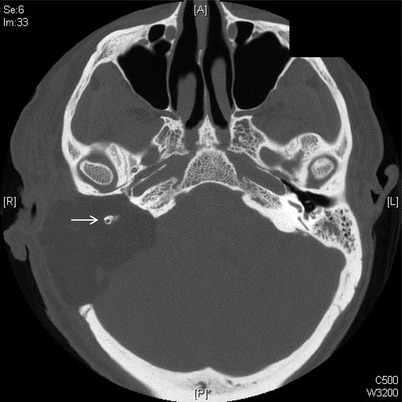

12.

Case 1. Axial CT of a cholesteatoma involving the jugular bulb. On exam, the squamous epithelium was visible within the hypotympanic region (arrow).

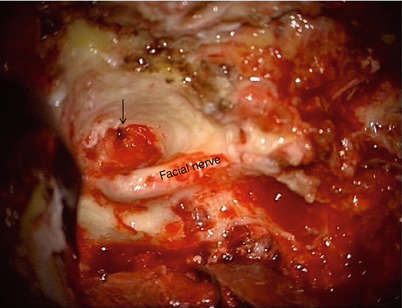

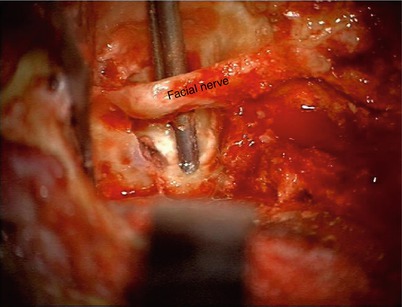

13.

A fallopian bridge technique was used to access the cholesteatoma and dissect it off the jugular bulb. The vertical segment of the facial nerve with a thin layer of bone seems to be floating in midair (arrowhead).

14.

More superiorly, a standard canal wall up with facial recess approach was performed. Ossicular chain reconstruction with a PORP was performed.

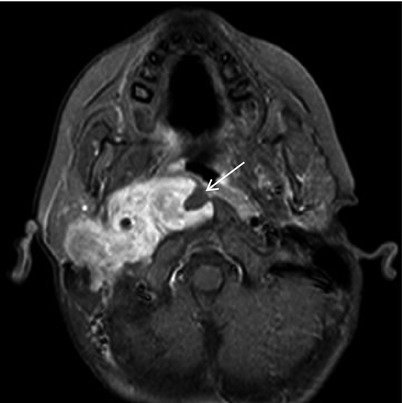

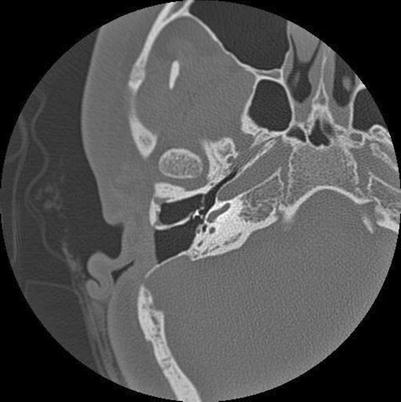

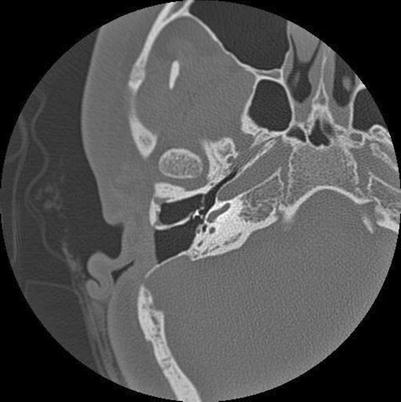

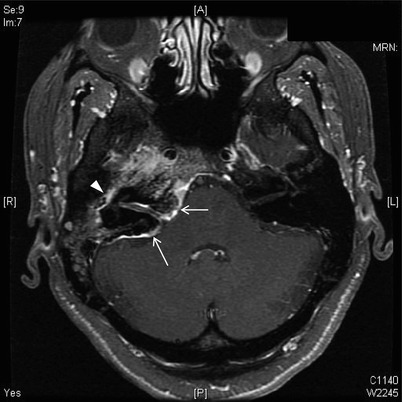

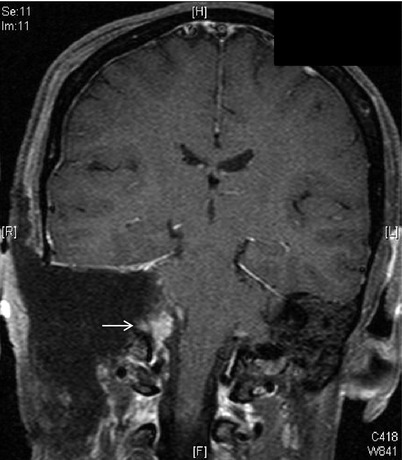

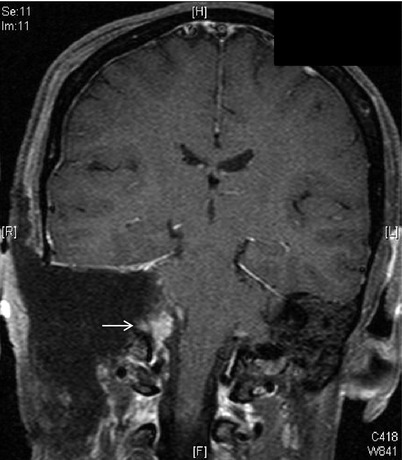

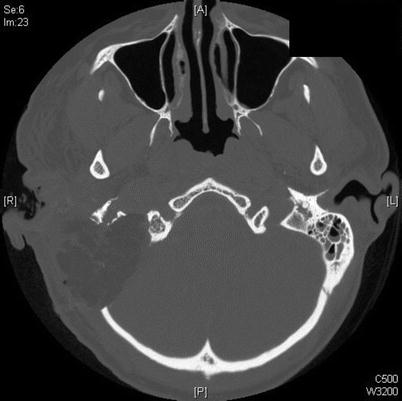

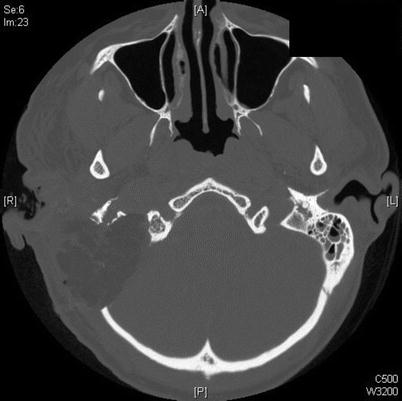

15.

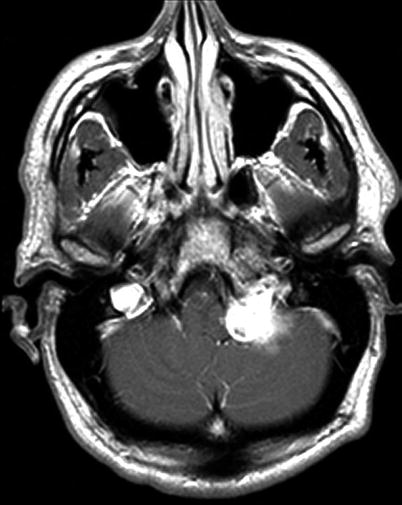

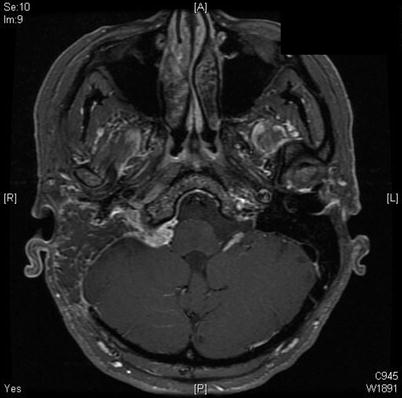

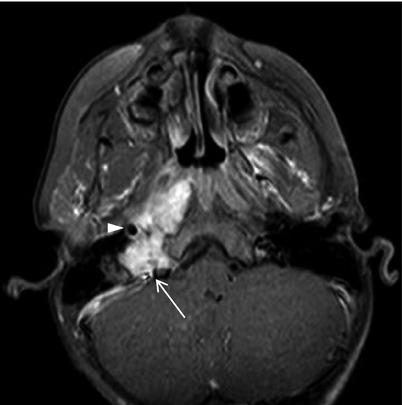

Case 2. Axial T1 MRI with gadolinium demonstrated a left posterior fossa schwannoma.

16.

A more inferior cut revealed that the tumor entered the jugular foramen. Thus, the tumor originated from CN IX, X, or XI. Exam demonstrated weakness of the left vocal cord consistent with a schwannoma of CN X.

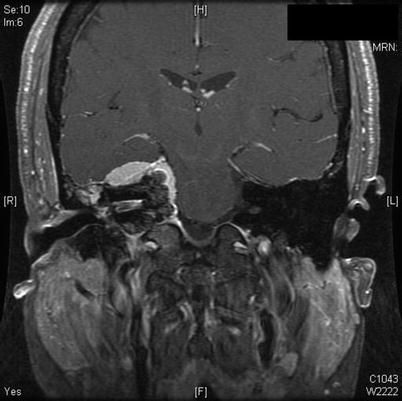

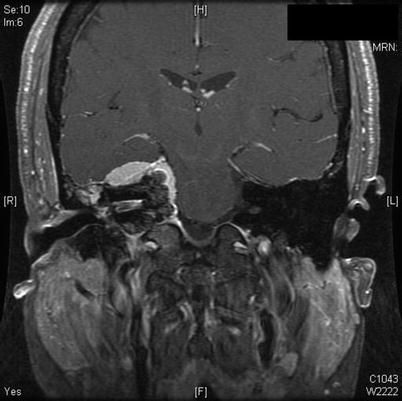

17.

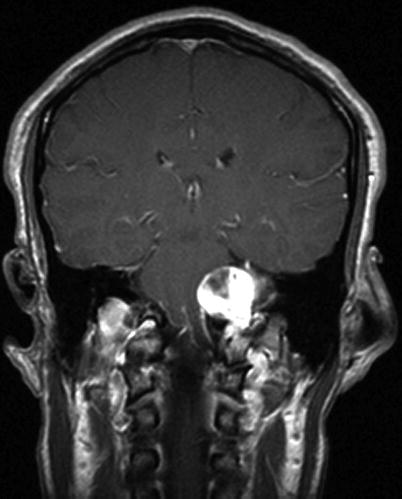

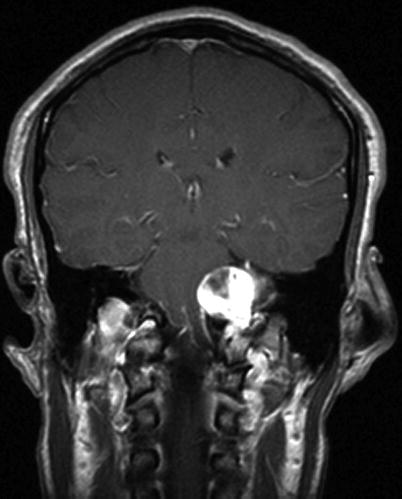

The coronal MRI clearly demonstrated how the schwanomma entered the jugular foramen. Because the tumor was primarily intradural with only minimal skull base bone involvement, a retrosigmoid approach was used as opposed to a formal postauricular infratemporal fossa approach.

18.

Postoperative T1 MRI with fat saturation demonstrates a near-total resection of the tumor. A small stub of tumor (arrow) was left in the jugular foramen to preserve the function of CN IX and XI. If we had wanted to remove this remnant, we could have drilled away the posterior lip of bone covering the jugular foramen. However, this would undoubtedly have affected function of these lower cranial nerves.

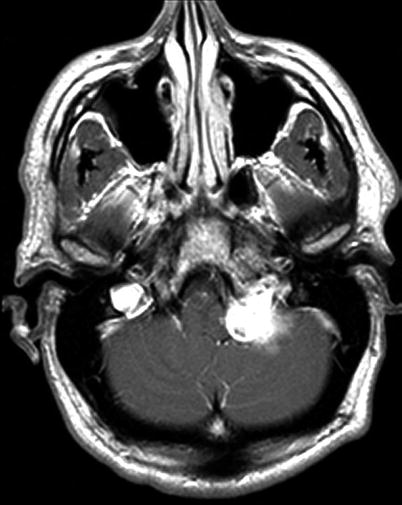

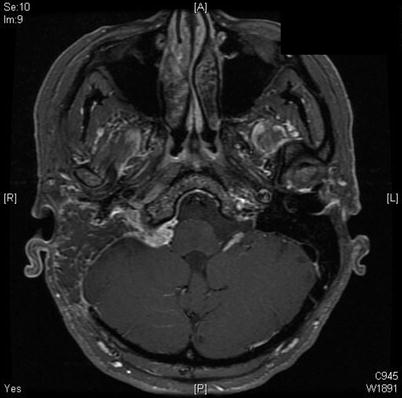

19.

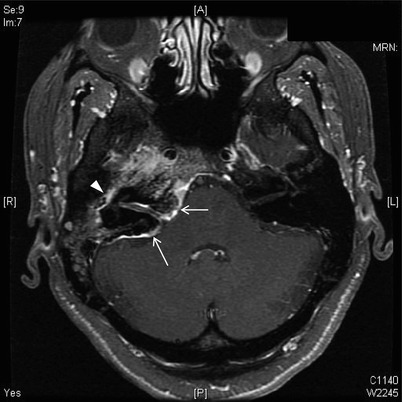

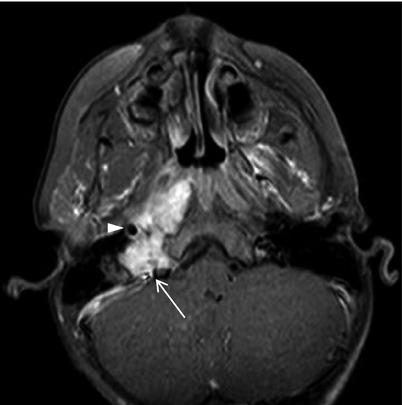

Case 3. A skull base meningioma that involved the temporal bone, otic capsule, and jugular foramen. There were hyperostotic changes to the posterior face of the temporal bone (arrows), and the internal auditory canal was narrowed. The dura enhanced from the sigmoid sinus all the way across the clivus. The enhancement lateral to the internal auditory canal was meningioma that infiltrated into the middle ear (arrowhead) and was visible on otoscopy in clinic as a white mass behind the tympanic membrane.

20.

Coronal T1 MRI of the same patient. The middle fossa dura was also involved.

21.

A pink mass was visible behind the right tympanic membrane in the posterior portion of the middle ear cavity. There was no serviceable hearing in the ear, thus a combined transjugular/transcochlear procedure was performed for access to the primary areas of tumor involvement: the middle fossa dura, the posterior fossa dura, the middle ear, the internal auditory canal, and the petrous apex. CN VII, IX, X, XI, and XII all had normal function. Therefore, we planned a subtotal resection with the goal of sparing their function while debulking the majority of the tumor.

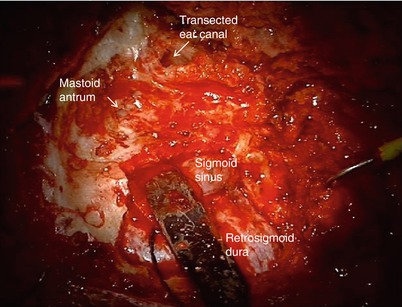

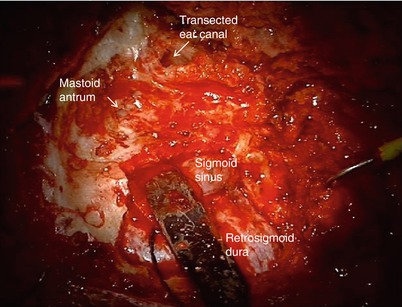

22.

The ear canal was transected and a standard mastoidectomy performed. The retrosigmoid dura was exposed and the malleable retractor placed on the sigmoid sinus.

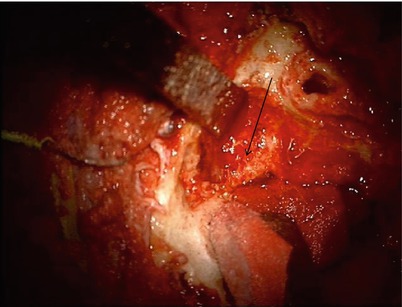

23.

Another retractor was placed on the middle fossa dura. The otic capsule bone of the semicircular canals (arrow) can be seen to be irregular and invaded with tumor.

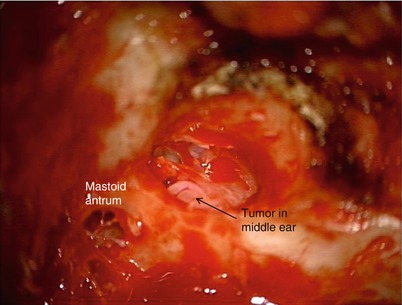

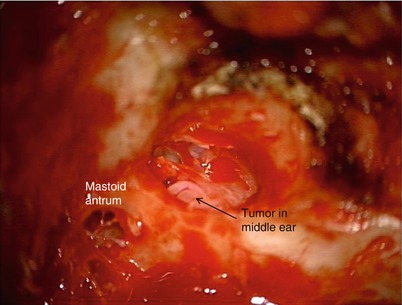

24.

Looking through the ear canal with the tympanic membrane removed, the tumor within the middle ear can be seen.

25.

The canal wall was removed and all the ossicles resected. A labyrinthectomy was performed and the facial nerve skeletonized around the second genu, leaving a thin bony fallopian canal intact. Note that all the skin of the ear canal has been removed. The Eustachian tube is visible (arrow).

26.

The promontory was then drilled, and tumor can be seen within the cochlea (arrow).

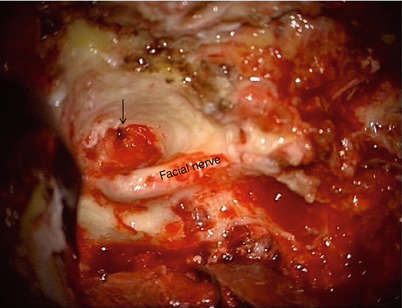

27.

After removal of the cochlea, the facial nerve fallopian bridge can be appreciated.

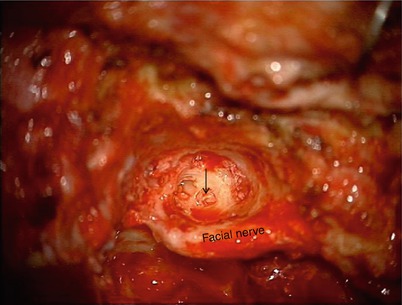

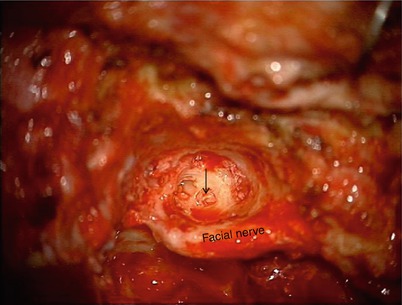

28.

The suction is visible around the facial nerve, demonstrating 360° skeletonization of the fallopian canal.

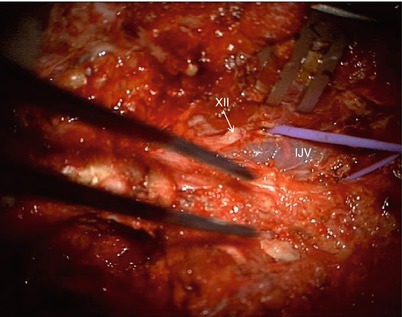

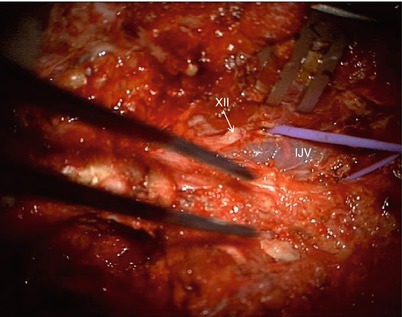

29.

The internal jugular vein (IJV) was identified in the neck and retracted with a rubber sling.

30.

A small stitch was placed through the outer leaflet of the retrosigmoid dura to use for retraction.

31.

The dura was lifted up with the suture to prevent injury to the cerebellum when opening the dura with an 11 blade scalpel. Once an initial opening was made, scissors were used to enlarge the opening.

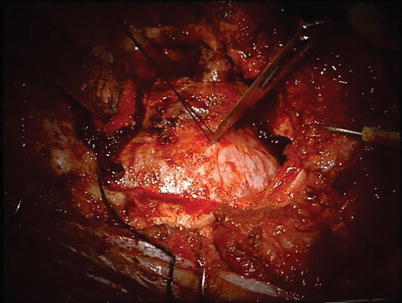

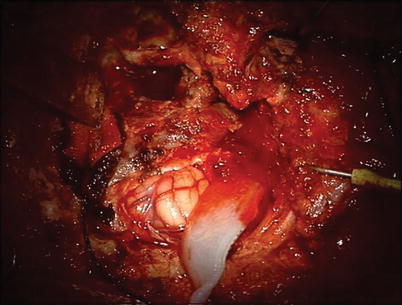

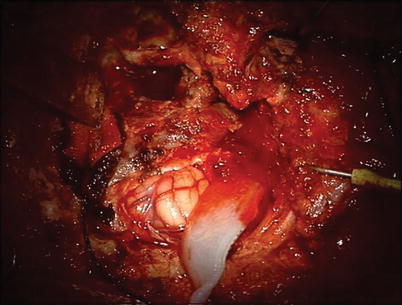

32.

The cerebellum was exposed, and a moist Telfa strip is placed on it for protection.

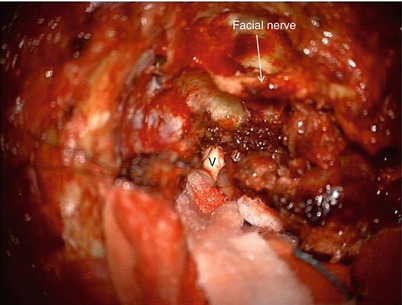

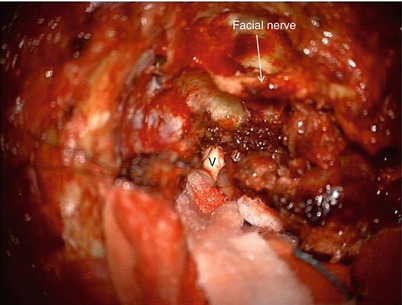

33.

More Telfa strips were placed on the cerebellum to help with retraction. The meningioma involved the sigmoid sinus and presigmoid dura. We did not need to tie the proximal sigmoid sinus because it was involved with tumor all the way to the junction of the transverse sinus and sigmoid sinus.

Since we did not plan a complete tumor resection, we elected to leave a little tumor in the sigmoid-transverse sinus junction. The benefit of this was that we did not need to work in this region and risk damaging the vein of Labbé. Complete tumor removal is not always achievable, and strategic decisions must be made regarding where tumor is left behind by assessing the potential morbidity of additional tumor removal versus the long-term risk of leaving residual tumor in this area. Should a small tumor remnant grow, it should be easily treated with stereotactic radiosurgery or possibly even external beam radiation.

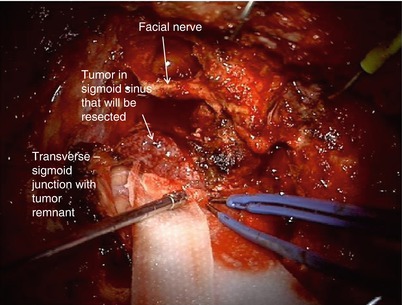

34.

In this view, the superior portion tumor was removed, while the tumor around the jugular foramen remained. CN V can be seen.

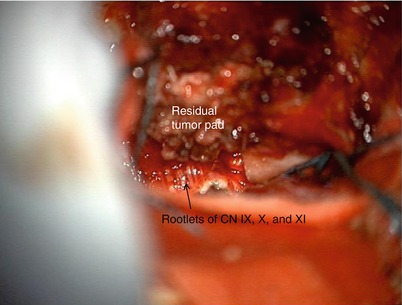

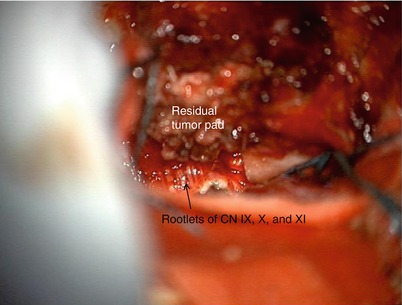

35.

Nerve rootlets of CN IX, X, and XI entered the jugular foramen, and the tumor remnant was reduced in size so as to not cause brain compression. We elected to leave this pad of tumor to spare cranial nerve function.

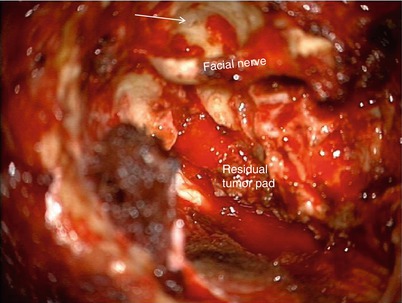

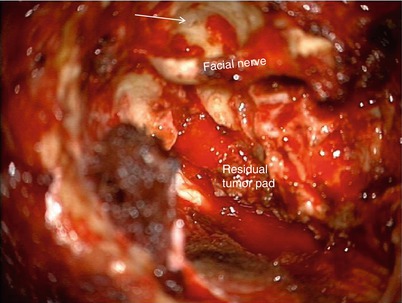

36.

The view at the conclusion of tumor resection. The pad of well-cauterized tumor remnant was visible at the jugular foramen. The ear canal was closed, the Eustachian tube was plugged (arrow), and a fat graft was placed into the cavity.

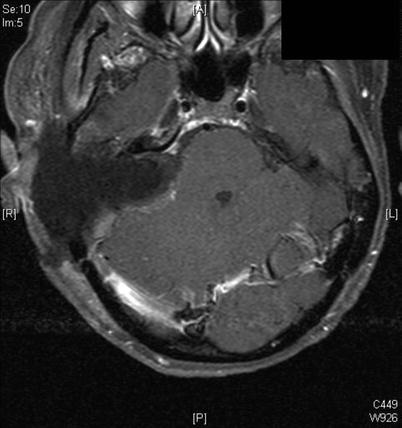

37.

Immediate postoperative axial MRI demonstrated that a complete temporal bone resection with resection of the jugular bulb was performed. The pad of residual tumor was visible (arrow).

38.

A more superior cut.

39.

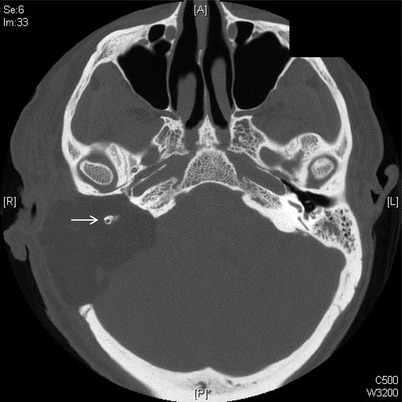

Coronal view demonstrated the tumor remnant (arrow) in the jugular foramen.

40.

Axial CT demonstrated the extent of bone removal and the fallopian bridge encompassing the vertical portion of the facial nerve (arrow).

41.

A lower cut demonstrated resection of the jugular bulb.

42.

Three months postoperatively, the fat graft was scarred in, and the tumor remnant remained unchanged.

43.

Axial T2 view demonstrated the fat graft and new dura that formed between it and the cerebellum (arrowheads).

44.

Case 4. Axial MRI with gadolinium of a child with recurrent neuroblastoma of the skull base and infratemporal fossa. She had failed chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Note that the tumor involved the left jugular foramen (arrow) and the internal carotid artery (arrowhead).

45.

A more inferior image demonstrates that the tumor encompassed the internal carotid artery and partially enveloped the prevertebral musculature (arrow).