Chapter 12B Language and Speech Disorders

Motor Speech Disorders: Dysarthria and Apraxia of Speech

Motor Speech Disorders: Overview

Motor speech disorders are syndromes of abnormal articulation, the motor production of speech, without abnormalities of language. A patient with a motor speech disorder can produce normal expressive language in writing and can comprehend both spoken and written language. If a listener transcribes the speech of a patient with a motor speech disorder into print or type and then reads it, the text should sound normal. Motor speech disorders include dysarthrias, disorders of speech articulation, and apraxia of speech, a motor programming disorder for speech, as well as four rarer syndromes: aphemia, the foreign accent syndrome, acquired stuttering, and the opercular syndrome. Duffy (1995), in an analysis of speech and language disorders at the Mayo Clinic, reported that 46.3% of the patients had dysarthria, 27.1% aphasia, 4.6% apraxia of speech, 9% other speech disorders (such as stuttering), and 13% other cognitive or linguistic disorders.

Dysarthrias

Dysarthrias involve the abnormal articulation of sounds or phonemes. The pathogenic mechanism in dysarthria is abnormal neuromuscular activation of the speech muscles, affecting the speed, strength, timing, range, or accuracy of movements involving speech (Duffy, 1995). The most consistent finding in dysarthria is the distortion of consonant sounds. Speech disorders can be mechanical, as in patients with physical disorders of the pharynx and larynx, but dysarthrias are neurogenic, related to dysfunction of the central nervous system, nerves, neuromuscular junction, or muscle, with a contribution of sensory deficits in some cases. Dysarthria can affect not only articulation but also phonation, breathing, and prosody (emotional tone) of speech. Total loss of ability to articulate is called anarthria.

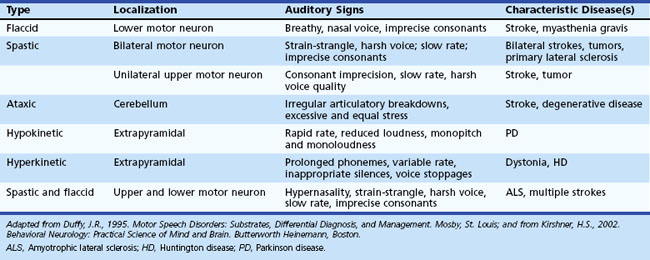

The Mayo Clinic classification of dysarthria (Duffy, 1995), widely used in the United States, includes six categories: (1) flaccid, (2) spastic and “unilateral upper motor neuron,” (3) ataxic, (4) hypokinetic, (5) hyperkinetic, and (6) mixed dysarthria. These types of dysarthria are summarized in Table 12B.1.

A milder variant of spastic dysarthria, unilateral upper motor neuron (UUMN) dysarthria, is associated with unilateral upper motor neuron lesions, such as strokes (Duffy, 1995). This type of dysarthria has similar features to spastic dysarthria, but UUMN dysarthria is less severe. Unilateral upper motor neuron dysarthria is one of the most common types of dysarthria, since it occurs in patients with unilateral strokes. In a study by Urban and colleagues (2006), left hemisphere strokes were more likely than right hemisphere strokes to be associated with dysarthria.

Ataxic dysarthria, associated with cerebellar disorders, is characterized by one of two patterns: irregular breakdowns of speech with explosions of syllables interrupted by pauses, or a slow cadence of speech with excessively equal stress on every syllable. The second pattern of ataxic dysarthria is referred to as scanning speech. A patient with ataxic dysarthria, attempting to repeat the phoneme /p/ as rapidly as possible, for example, produces either an irregular rhythm, resembling popcorn popping, or a very slow rhythm. Causes of ataxic dysarthria include cerebellar strokes, tumors, multiple sclerosis, and cerebellar and spinocerebellar degenerations. A recent report localized ataxic dysarthria to the upper cerebellar loci of the quadrangularis and simplex lobules by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Ogawa et al., 2010).

Hypokinetic dysarthria, the typical speech pattern in Parkinson disease (PD), is notable for decreased and monotonous loudness and pitch, rapid rate, and occasional consonant errors. In a study of brain activation by positron emission tomography (PET) methodology, Liotti and colleagues (2003) described premotor and supplementary motor area activation in patients with PD and untreated hypokinetic dysarthria, but not in normal subjects. After completion of a voice treatment protocol, these premotor and motor activations diminished, whereas right-sided basal ganglia activations increased.

The management of dysarthria includes speech therapy techniques to strengthen muscles, train more precise articulations, slow the rate of speech to increase intelligibility, or teach the patient to stress specific phonemes. Devices such as pacing boards to slow articulation, palatal lifts to reduce hypernasality, amplifiers to increase voice volume, communication boards for subjects to point to pictures, and augmentative communication devices and computer techniques can be used when the patient is unable to communicate in speech. Visual cues may help dysarthric speakers become more intelligible (Hustad and Garcia, 2005). Surgical procedures such as a pharyngeal flap to reduce hypernasality or vocal fold Teflon injection or transposition surgery to increase loudness may help the patient speak more intelligibly. Treatment of PD can improve dysarthria in terms of both speech therapy and pharmacological treatments (DeLetter et al., 2005; Pinto et al., 2004; Trail et al., 2005), but surgical or deep brain stimulation procedures occasionally result in worsened intelligibility (Farrell et al., 2005; Guehl et al., 2006). In general, few randomized trials have examined the efficacy of speech therapy techniques for dysarthria (Sellars et al., 2005). A more detailed discussion of dysarthria can be found in Kirshner (2002).