Elizabeth Bundock MD, PhD.

Written in conjunction with

In addition to the widely infiltrating tumors discussed in Chapter 6, several other neoplasms either elaborate glial processes or arise from cells having a glial ontogeny. Smears exquisitely reveal glial architecture and hence provide either diagnostic or useful information about these tumors. Two low-grade gliomas that have only a limited capacity to infiltrate brain are pilocytic astrocytomas (PA) and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA). Both gliomas create a glial matrix, put glial tentacles into adjacent brain, and can infiltrate the leptomeninges. Ependyma line the ventricles as epithelial cells but also extend glial processes to nearby vessels. Tumors derived from these cells manifest their dual epithelial and glial properties. Although the choroid plexus is purely epithelial, it derives from an invagination of ependymal cells that accompany leptomeninges and vessels into the ventricular system. This chapter discusses the smears of these low-grade, glial-derived tumors.

Pilocytic Astrocytoma

Pilocytic astrocytomas afflict a wide age range of patients but most commonly present in children and adolescents. These slowly growing tumors, although considered grade I neoplasms, may originate in regions where complete resection is difficult. Patients develop progressive ataxia (cerebellum), seizures (temporal lobe), and other focal neurologic deficits (brainstem or spinal cord).

About half of the pilocytic astrocytomas develop in the posterior fossa, where they create cerebellar dysfunction or hydrocephalus. Within the cerebellum, they grow in the vermis or hemispheres. The tumors typically have a solid mass of cells associated with one or several cysts. Vessels within the solid mass lack a blood–brain barrier and hence enhance strongly after administration of gadolinium (Figure 7-1). The cystic components lack vessels, do not enhance, and show T2-hyperintensity signal characteristics of free water. Brainstem pilocytic astrocytomas grow as exophytic masses off its vital structures. Remaining tumors occur in the cerebral hemispheres, optic pathway (optic nerve, chiasm, floor of third ventricle), and spinal cord. In adults, pilocytic astrocytomas tend to be supratentorial.

With the unaided eye or at low magnification, smears reveal the glial ontogeny of these tumors. The dense, fibrillary parts of this biphasic tumor shear out in jagged, interconnected clumps, reminiscent of pulling apart cotton (Figure 7-2). As increasing forces break down the tumor across the slide, the clumps fragment into cells. It is the edges of the clumps or the more isolated cells that are most informative.

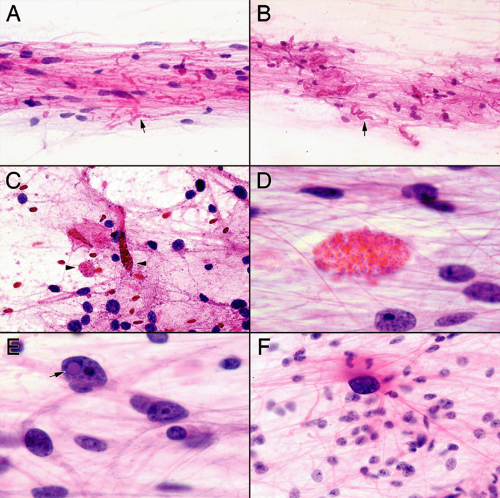

Low magnification reveals the fibrillary nature of these tumors (Figure 7-3). Like the hackles standing up on the back of an alert dog, from the edges of the thicker clumps radiate fine fibrillary processes. The cellularity of the clumps and their thinner radiating processes indicates a neoplasm rather than a reactive process. Fine capillaries and some thickened vessels may be present (Figure 7-3, A and C). Finding massively thickened vessels with piled-up tumor cells should suggest a high-grade glioma rather than a pilocytic astrocytoma. Like other astrocytic tumors, cellular bridges built of glial processes interconnect the clumps of cells (Figure 7-3B). Samples from microcystic areas of the tumor show a basophilic hue among the fine processes. Thinner zones in the smear best reveal the fine astroglial properties of this tumor.

Intermediate microscopic powers provide the best diagnostic clues in a pilocytic astrocytoma smear. At the edges of the clusters and in thinner or more dispersed regions of the slide, long, hairlike, or “piloid” processes

radiate long distances from many tumor cells (Figure 7-4). It is these slender, bipolar, and stellate cells that are most characteristic of this tumor. These distinctly differ from the shorter, stubbier, more irregular processes of the infiltrating gliomas. By themselves, these bipolar cells are indistinguishable from certain reactive astrocytes; it is the nearly monomorphic population of such cells that implicates a pilocytic astrocytoma. Like most intrinsic brain

tumors, complete cellular uniformity is the exception rather than the rule. These tumors may have plump rather than slender cells. Some multinucleation or pleomorphism is common. However, the overall population of tumor nuclei tends to be low grade and monotonous. Intermediate powers also reveal looser, basophilic, more myxoid areas and denser regions filled with Rosenthal fibers. Neuropathologists breathe a sigh of relief after finding Rosenthal fibers, because these structures commonly accompany this tumor. The catchy term pleases the neurosurgeon seeking straightforward answers. These condensations of alphaB-crystalin and glial fibrillary acidic protein jump out of the smear as brightly eosinophilic, slightly refringent structures among glial strands. Although not diagnostic of a pilocytic astrocytoma, they add comfort in the proper settings.

radiate long distances from many tumor cells (Figure 7-4). It is these slender, bipolar, and stellate cells that are most characteristic of this tumor. These distinctly differ from the shorter, stubbier, more irregular processes of the infiltrating gliomas. By themselves, these bipolar cells are indistinguishable from certain reactive astrocytes; it is the nearly monomorphic population of such cells that implicates a pilocytic astrocytoma. Like most intrinsic brain

tumors, complete cellular uniformity is the exception rather than the rule. These tumors may have plump rather than slender cells. Some multinucleation or pleomorphism is common. However, the overall population of tumor nuclei tends to be low grade and monotonous. Intermediate powers also reveal looser, basophilic, more myxoid areas and denser regions filled with Rosenthal fibers. Neuropathologists breathe a sigh of relief after finding Rosenthal fibers, because these structures commonly accompany this tumor. The catchy term pleases the neurosurgeon seeking straightforward answers. These condensations of alphaB-crystalin and glial fibrillary acidic protein jump out of the smear as brightly eosinophilic, slightly refringent structures among glial strands. Although not diagnostic of a pilocytic astrocytoma, they add comfort in the proper settings.

No single microscopic feature in either the smear or in permanent sections is pathognomonic for a pilocytic astrocytoma. The diagnosis of this neoplasm requires combining several or multiple distinct features. High-power views of their smears (Figure 7-5) demonstrate piloid cells having relatively monotonous, slightly elongated nuclei with long, exceedingly thin and delicate processes. However, many of the tumor cells have either multiple processes or lack any associated fibers. Like flies on a spider web, bland nuclei often appear stuck onto the fine but dense glial network. In denser regions, where the smear has sheared the tissue less, nuclei tend to be more oval-to-round, rather than elongated. Although many astroglial fibers radiate directly off the nuclei, others will arise from a distinct, eccentric mass of eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Ancillary features (Figure 7-6) of Rosenthal fibers, occasional granular bodies, and a few pleomorphic cells reinforce a diagnosis of pilocytic astrocytoma. Granular bodies, like Rosenthal fibers, are not specific to this tumor, although they significantly support the diagnosis. The tinctorial properties of these bodies are similar to Rosenthal fibers: eosinophilic and slightly refringent. Structurally, a multitude of red vacuoles or granules pack their cytoplasm. Some of these bloated cells might survive the smear, although many likely succumb to its shearing forces. If you see them on the smear, use them, but do not waste time looking for them in the frozen section room.

Permanent sections of pilocytic astrocytomas recapitulate many of the features presented by the intraopera-tive smears (Figure 7-7). At low power, a classic tumor displays a biphasic histology of dense and loose areas. Dense zones contain more glial fibers, fusiform cells, and perhaps scattered Rosenthal fibers. These regions match the more cohesive zones on the smear and furnish dense, cellular islands interconnected by glial bridges. The loose areas have a lighter glial matrix and cells with rounded nuclei. Artefactual perinuclear halos might suggest an oligodendroglioma; however, purge this diagnosis from the cerebellum, brainstem, or spinal cord because oligodendroglioma is overwhelmingly a supratentorial tumor. Smears easily resolve the dilemma because low-grade oligodendroglioma nuclei usually swim in only a light matrix, whereas pilocytic astrocytomas typically elaborate a strong glial matrix. Loose areas often contain microcysts and a slight myxoid matrix. Myxoid material with its more relaxed matrix displays well in a smear. The tumor often shows subarachnoid growth, which is an architectural topology not demonstrable in smears. Rosenthal fibers, eosinophilic granular bodies, multinucleated cells (“pennies-on-a-plate”), and occasional pleomorphic cells can be present in both the permanent section and the smear.

Difficulties in diagnosis during an intraoperative consultation arise when a tumor only has a subset of features. A tumor with a piloid background and some pleomorphic or multinucleated cells, but without Rosenthal fibers or eosinophilic granular bodies, could suggest an infiltrating high-grade glioma. Although extra architectural features in a frozen section might assist the smear, its usual artifacts of poor nuclear detail, ice crystals confused for microcysts, and limited sampling often add little additional information. When in doubt, add the frozen section to the smear but without a doubt, do the smear and sample widely: it will augment your intraoperative and final diagnosis.

Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma

Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) is an uncommon low-grade glioma that develops most frequently in children and adolescents. Patients often have a long history of seizures. It is typically a superficial, supratentorial tumor, with a predilection for the temporal lobes.

The classic radiographic appearance is a cystic mass with a prominently enhancing mural nodule adjacent to the cortex (Figure 7-8), although solid, well-circumscribed masses are also common. Like other slowly growing glial neoplasms, the tumor frequently involves the leptomeninges. Their ability to remodel the skull’s inner table reflects their slow growth. These indolent tumors do not involve dura and bone; such involvement should prompt consideration of a mesenchymal neoplasm.

The diagnosis of PXA during intraoperative consultation is particularly challenging because many of its cytologic and histologic features resemble a high-grade

glioma. The prognosis of PXA is, however, significantly better than most of the infiltrating gliomas. Knowledge of the patient’s age, clinical history, and radiographic appearance of the tumor are essential for making the correct diagnosis.

glioma. The prognosis of PXA is, however, significantly better than most of the infiltrating gliomas. Knowledge of the patient’s age, clinical history, and radiographic appearance of the tumor are essential for making the correct diagnosis.

PXAs typically invoke a significant desmoplastic response at the surface of the brain. Chronic inflammatory cells cuff vessels and percolate through the tumor. Especially at the surface, the tumor induces some fibrosis and lays down reticulin scaffolding. This reticulin-glial-fibrotic

matrix makes the tissue somewhat more difficult to smear (Figure 7-9). Occasionally, large clumps contain shifting streams of spindled cells, reflecting areas of fascicular growth. Such samples only reluctantly relinquish a few isolated cells. Deeper aspects of the tumor invoke less desmoplasia, so a good biopsy with adequate sampling should release some informative cells.

matrix makes the tissue somewhat more difficult to smear (Figure 7-9). Occasionally, large clumps contain shifting streams of spindled cells, reflecting areas of fascicular growth. Such samples only reluctantly relinquish a few isolated cells. Deeper aspects of the tumor invoke less desmoplasia, so a good biopsy with adequate sampling should release some informative cells.

Intermediate magnifications better demonstrate this tumor’s astroglial origin (Figure 7-10). Various fine and

thicker processes protrude out from the clumps of cells, leaving a somewhat ragged border. Glial bridges span cellular clusters. However, these features are common to most astrocytic neoplasms and do not specifically suggest a PXA. The characteristic feature of this tumor, which should aid in its diagnosis, is its large, bizarre, pleomorphic cells. When present, these stand out of the smear, even at low magnifications. However, pleomorphic cells also frequently accompany the much more common glioblastoma. Unless an astrocytic tumor has a characteristic PXA radiology or an unusual clinical presentation, finding such pleomorphic cells in an astrocytoma will strongly and only occasionally incorrectly suggest a high-grade glioma.

thicker processes protrude out from the clumps of cells, leaving a somewhat ragged border. Glial bridges span cellular clusters. However, these features are common to most astrocytic neoplasms and do not specifically suggest a PXA. The characteristic feature of this tumor, which should aid in its diagnosis, is its large, bizarre, pleomorphic cells. When present, these stand out of the smear, even at low magnifications. However, pleomorphic cells also frequently accompany the much more common glioblastoma. Unless an astrocytic tumor has a characteristic PXA radiology or an unusual clinical presentation, finding such pleomorphic cells in an astrocytoma will strongly and only occasionally incorrectly suggest a high-grade glioma.

Although a cursory high-power look at such a tumor would suggest a glioblastoma, a careful examination of the smear should reveal some discordant features (Figure 7-11). Our eyes tend to focus on the obvious. Certainly glance at the monstrous cells on the smear. However, focus on the main tumor cell population. These will usually be much more monomorphic and rounded than the occasional bizarre cell. High-grade gliomas typically produce thickened, irregular processes and a coarse matrix, whereas the matrix of a PXA is often reminiscent of a pilocytic astrocytoma. In the smear, delicate or fine processes, piloid cells, inflammation, occasional eosinophilic granular bodies, and Rosenthal fibers should all challenge the diagnosis of a high-grade neoplasm (Figure 7-11B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree