Parkinson-Plus Syndromes

Paul Greene

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson disease (PD) is the most common cause for a dopamine deficiency syndrome, but other causes for this syndrome had been identified from a small number of pathologic examinations since the early 20th century. It was not until the introduction of levodopa to treat PD in the late 1950s and early 1960s that clinicians began to identify patients who had dopamine deficiency signs but, unlike patients with PD, had minimal or no improvement with levodopa. Because multiple causes for levodopa-unresponsive dopamine deficiency states were soon identified, such patients were said to have parkinsonism or Parkinson-plus syndromes.

PROGRESSIVE SUPRANUCLEAR PALSY, MULTIPLE SYSTEM ATROPHY, CORTICOBASAL DEGENERATION

The three most common Parkinson-plus syndromes are progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), multiple system atrophy (MSA), and corticobasal degeneration (CBD).

HISTORY

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

In 1964, Steele, Richardson, and Olszewski reviewed autopsies of patients who had a syndrome of pseudobulbar palsy, supranuclear ocular palsy (chiefly affecting vertical gaze), axial rigidity and dystonia, early loss of postural reflexes, and dementia. They found a pattern of neuronal degeneration and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), chiefly affecting the pons and midbrain. This condition became known as the Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome or PSP. As more autopsies became available, it became clear that this characteristic pathology could also produce other patterns of initial symptoms in addition to the originally described disease now called Richardson syndrome. In progressive supranuclear palsy-parkinsonism (PSP-P), patients in the early stage of the disease resemble idiopathic PD. However, occasional patients with PSP pathology may also present with corticobasal syndrome (see the following text), progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA), akinesia with gait freezing, primarily ataxia, or even pure dementia.

Multiple System Atrophy

It was noticed as early as 1900 that some patients with parkinsonian signs had additional signs and symptoms referable to other brain systems: cerebellar dysfunction (called olivopontocerebellar atrophy or OPCA) or autonomic dysfunction (termed Shy-Drager syndrome or SDS). Another syndrome of rapidly progressive parkinsonism with neuronal loss and gliosis primarily in the putamen and substantia nigra but no Lewy bodies on autopsy was termed striatonigral degeneration (SND). It was eventually noticed that some patients had elements of all these syndromes, and that patients with one clinical syndrome might have pathology overlapping with the other syndromes. The term multiple system atrophy (MSA) was introduced to indicate that SND, SDS, and OPCA were all part of a single disease spectrum. The later identification of a common pathology (synuclein-containing glial cytoplasmic inclusions) confirmed the suspicion that these conditions represented one disease (Table 84.2). Some patients with MSA have upper motor neuron signs and one of the original SDS patients had lower motor signs as well. It is not clear how many patients with parkinsonism and motor neuron disease have the pathology of MSA, so that the current criteria for MSA do not include the parkinsonism-amyotrophy syndrome. Because most patients have some degree of autonomic dysfunction, the disease is now characterized according to the presenting motor dysfunction: MSA-P when parkinsonism dominates the picture and MSA-C when cerebellar dysfunction predominates.

Corticobasal Degeneration

Initially reported as corticodentatonigral degeneration with neuronal achromasia in 1967, this disorder was characterized clinically by a combination of levodopa-unresponsive parkinsonism with early loss of balance, severe unilateral limb dystonia, and almost any focal cortical deficit. The pathology was also characteristic: enlarged achromatic neurons in cortical areas (particularly parietal and frontal lobes) along with nigral and striatal neuronal degeneration without Lewy bodies. The syndrome, also called cortical-basal ganglionic degeneration in the past, is now usually called corticobasal degeneration (CBD). As with PSP, it is now recognized that this pathology can also present clinically in other ways: as a frontal behavioral-spatial syndrome, PNFA, a progressive supranuclear palsy-like syndrome (PSPS), and dementia without motor abnormalities. Because patients with the pathology of PSP may mimic CBD, the original clinical syndrome is now called corticobasal syndrome. The overlap in both pathology and clinical features between CBD and PSP has raised concerns that the two diagnoses may represent a spectrum of a single disease despite a small number of pathologic findings unique to each diagnosis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The reported prevalence of each syndrome varies dramatically. In part, this is because clinical studies tend to underestimate the prevalence, whereas autopsy studies tend to overestimate the prevalence (because unusual cases are more likely to come to autopsy). PSP is the most common, generally reported in clinical studies to have a prevalence of 1 to 20 per 100,000 (compared to 100 to 200 per 100,000 for PD). In a large autopsy study, of all patients diagnosed with parkinsonism, about 4% had a pathologic diagnosis of PSP, about 2% had MSA, and about 1% had CBD (compared with more than 60% with PD).

PATHOBIOLOGY

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

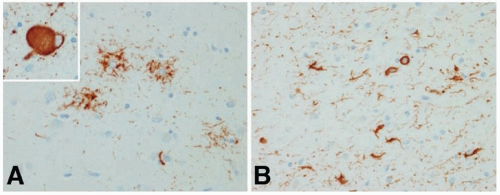

Atrophy of the dorsal midbrain, globus pallidus, and subthalamic nucleus; depigmentation of the substantia nigra; and mild dilatation of the third and fourth ventricles and aqueduct are seen on gross visual inspection of the postmortem brain in typical PSP. Light microscopy shows neuronal loss with gliosis, numerous NFTs, and neuropil threads in many subcortical structures, including the subthalamic nucleus, pallidum, substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, periaqueductal gray matter, superior colliculi, nucleus basalis, inferior olive, red nucleus, oculomotor nuclei, and cerebral cortex, especially the prefrontal and precentral areas. The NFTs appear as skeins of fine fibrils, often globose in shape in brain stem neurons. Ultrastructurally, they are composed of short, straight 12- to 15-nm tubules arranged in circling and interlacing bundles containing neurofilament proteins and the neurotubule-associated protein tau. In PSP, inclusion of exon 10 of tau creates a predominance of four repeated microtubule-binding domains, compared with a mixture of three and four repeated domains in Alzheimer disease. The typical astrocytic lesion in PSP is the tufted astrocyte, in contrast to the astrocytic lesion in CBD, the astrocytic plaque (see following text). Coiled bodies consisting of NFTs are found in astrocytes in both PSP and CBD (Fig. 84.1).

Multiple System Atrophy

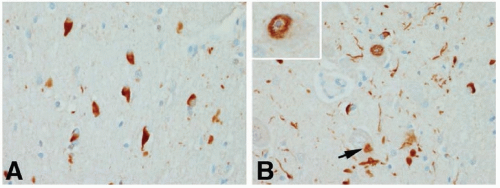

The full pathologic spectrum of MSA consists of neuronal loss and gliosis in the neostriatum, substantia nigra, globus pallidus, cerebellum, inferior olives, basis pontine nuclei, intermediolateral horn cells, corticospinal tracts, and, rarely, anterior horn cells. A characteristic pathologic feature is the presence of widespread glial cytoplasmic inclusions, particularly in oligodendroglia. These argyrophilic, α-synuclein-positive, perinuclear structures are primarily composed of straight microtubules containing ubiquitin and tau protein. In SND, nerve cell loss and gliosis are found predominantly in the substantia nigra and neostriatum. In SDS, the preganglionic sympathetic neurons in the intermediolateral horns are lost. In addition, other areas may be affected, particularly the substantia nigra (to produce parkinsonism), the cerebellum (to cause ataxia), and the striatum (to cause lack of response to levodopa). In OPCA, there is degeneration of the olives, pons, and cerebellum as well as neuronal loss in the striatum and substantia nigra. Less often, the anterior horn cells are involved (to cause amyotrophy) (Fig. 84.2).

Corticobasal Degeneration

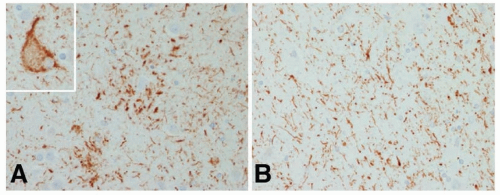

In CBD there is asymmetric atrophy usually most severe in the frontoparietal region with relative sparing of the occipital lobes. Swollen vacuolated neurons are found in the atrophic cortical areas and to a lesser degree in the affected subcortical regions. These swollen or ballooned neurons contain phosphorylated neurofilaments and sometimes tau and ubiquitin. There is neuronal loss and gliosis in affected cortex and in the globus pallidus, putamen, red nucleus, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, locus ceruleus, and to a lesser degree in the dentate nucleus. Remaining neurons in affected areas contain the globose tangles common in PSP, in this setting called corticobasal bodies. As in PSP, white matter is affected with a variety of abnormalities including tau-containing fibrils coiling around the nuclei of oligodendroglia (coiled bodies). The typical glial finding in CBD is not the tufted astrocyte common in PSP but tau-containing processes surrounding astrocytes called astrocytic plaques. As in PSP, 4-repeat tau predominates but the insoluble tau fragments in CBD have a different ultrastructure from the insoluble fragments of tau in PSP (Fig. 84.3).

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Patients with classical PSP or Richardson syndrome have an akinetic rigid Parkinson-like syndrome with early loss of postural reflexes, falls, and dementia and usually have a supranuclear palsy early in the course. Rest tremor, asymmetric onset, and improvement with levodopa are uncommon. Axial rigidity often exceeds limb rigidity, and the posture may be erect. Patients have facial dystonia with deep nasolabial folds and furrowed brow (Procerus sign), an appearance of surprise or concern. When the patient walks, the neck may be extended, the arms abducted at the shoulders and flexed

at the elbows. Dysphagia and dysarthria usually appear early and become severe. The voice is slurred and hoarse, and some patients become anarthric as the disease progresses. Gait “freezing” may be prominent, and transient arrest of motor activity interrupts walking, speaking, and/or other actions.

at the elbows. Dysphagia and dysarthria usually appear early and become severe. The voice is slurred and hoarse, and some patients become anarthric as the disease progresses. Gait “freezing” may be prominent, and transient arrest of motor activity interrupts walking, speaking, and/or other actions.

The first visual symptoms in Richardson syndrome are failure to maintain eye contact in social interactions and difficulty with tasks requiring downgaze, such as reading, eating, or descending stairs. Hesitation on voluntary downgaze is found on examination accompanied by loss of vertical opticokinetic nystagmus on downward movement of the target. Patients often complain of diplopia, blurred vision, or difficulty reading. Disturbances of eyelid motility are also common, including lid retraction (resulting in a staring expression), blepharospasm, and apraxia of eyelid opening or closing. Eyelid opening and closing apraxia (which are probably not true apraxia) are far more common in PSP than in any other extrapyramidal disorder. Fixation instability with coarse squarewave jerks and faulty suppression of the vestibulo-ocular reflex are common.

The cognitive impairment of PSP syndromes has been considered the archetype of subcortical dementia. The striking features are severe bradyphrenia (slowed thought), impaired verbal fluency, and difficulty with sequential actions or shifting from one task to another. Cognitive tests that depend on visual performance are especially affected. Apathy and disinhibition are common. Impulsiveness compounds postural instability and often leads to behavior that accentuates fall risk. Emotional incontinence is dominated by inappropriate weeping or, less frequently, laughing.

The course of PSP is aggressive; 3 to 4 years after onset, patients cannot walk without assistance and at a median of 5 years after onset, they are confined to bed and chair. They succumb to infection (from aspiration or pressure ulcers) or the sequelae of falls. The course varies according to the clinical syndrome, but Richardson syndrome has inexorable deterioration, culminating in death in 6 to 10 years in most cases.

In PSP-P, falls, dementia, and supranuclear palsy develop later and patients are more likely to have an asymmetric onset, rest tremor, and response to levodopa early in the course (although these usually do not persist). In some patients with PSP pathology, depending on the distribution of pathology, language difficulty may precede motor signs, presenting as a dysarthric, slow expressive aphasia (called primary progressive aphasia or progressive nonfluent aphasia). In a small number of patients, variation in pathology may produce other initial syndromes: freezing and balance difficulty without significant rigidity (akinesia with gait freezing), pure dementia without significant motor deficits, cerebellar syndrome, or corticobasal syndrome (see the following text) (Videos 84.1 and 84.2).

Multiple System Atrophy

The defining symptoms of SND are those of parkinsonism without tremor. Progression is usually rapid, and beneficial response to levodopa is absent or slight, presumably because striatal neurons containing dopamine receptors are usually lost. Dystonic reactions are common following low-dosage levodopa therapy. Orthostatic hypotension is a common presenting symptom of SDS syndrome (sometimes with labile blood pressure), but other dysautonomic symptoms are also troublesome, including impotence, urge incontinence, incomplete bladder emptying, and gastrointestinal (GI) motility disorders. Laryngeal stridor (often at night but sometimes during the day as well) strongly suggests SDS syndrome and can be life threatening. Other sleep symptoms include dysrhythmic breathing, sleep, and central apnea. OPCA is characterized by a mixture of parkinsonism and cerebellar syndrome, including gait ataxia, dysmetria, scanning speech, nystagmus, hypometric saccades, supranuclear upgaze impairment, and other cerebellar eye movement abnormalities. The least common presentation of MSA involves amyotrophy mimicking amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (often combined with parkinsonism). Some patients with pathologic MSA may have pure autonomic failure for many years before developing other symptoms (and some may have the pathology and eventually develop symptoms of Lewy body disease). Dementia in MSA is rarely severe. As noted earlier, combinations of these symptoms often occur. Most patients progress rapidly and are in a wheelchair by a median 6 to 7 years after onset, although patients with cerebellar deficit predominance seem to progress more slowly. As in other Parkinson-plus syndromes, patients die from pulmonary, urinary tract and pressure ulcer infections, and complications of falls. Unlike the other syndromes, patients with MSA are also at risk for cardiopulmonary arrest due to autonomic dysfunction.

Corticobasal Degeneration

The onset of CBD is insidious and typically unilateral, with focal cortical deficits, and often marked rigidity-dystonia in the involved arm and/or leg. Sustained postures leading to contractures are common. Bradykinesia is usually present but may be hard to detect in the dystonic limb or limbs. Cortical signs of apraxia, alien limb phenomenon, cortical sensory loss, cortical reflex myoclonus, and occasionally aphasia are usually dramatic. In addition to focal signs, global cortical dysfunction (dementia) is common. Speech is hesitant and dysarthric, gait is poor, and occasionally action tremor is evident. Falls usually occur shortly after onset of the disease. The disease usually spreads slowly to involve both sides of the body, and supranuclear gaze difficulties can occur late in the course. Patients with CBD pathology may present with several other syndromes. In the frontal behavioralspatial syndrome, patients present with some combination of executive dysfunction, behavioral change, and visuospatial deficits. CBD at the onset may also look like PSP, PNFA, or a dementia without characteristic motor or focal cortical features (Video 84.3).

DIAGNOSIS

There have now been consensus criteria for the diagnosis of each of these syndromes. They were developed primarily for clinical research but are commonly used for clinical diagnosis as well (Tables 84.1, 84.2, 84.3).

Levodopa-unresponsive parkinsonism with early involvement of gait and balance suggests a Parkinson-plus syndrome, most commonly PSP, MSA, or CBD. There are two challenges: (1) Can we identify patients with signs and symptoms of one disease but the pathology of another? (2) Can we identify patients who seem to have idiopathic PD early in the course but actually have one of these syndromes?

It is not possible to predict the underlying pathology 100% of the time. Supranuclear vertical ophthalmoplegia suggests Richardson disease. Vertical eye movements are usually affected first in PSP whereas they develop late in CBD and are usually horizontal in MSA. Significant cerebellar deficits are most common in MSA but are rarely present in PSP. Autonomic failure is a hallmark of MSA and is uncommon in PSP and CBD but can be prominent in diffuse Lewy body disease (DLBD). Significant cognitive impairment is common is PSP and CBD but uncommon in MSA. Focal cortical deficits are a defining feature of CBD but occur in a minority of patients with PSP. Visual hallucinations and dopa-dyskinesias are more likely to be present in PD than in PSP-P or the other syndromes. Vascular parkinsonism often meets criteria for a Parkinson-plus syndrome and can be mistaken for PSP if eye movements are involved. Vascular parkinsonism can only be present with significant magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormality, but white matter disease on MRI does not exclude PSP, MSA, or CBD. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)-parkinsonism can mimic any of these conditions, especially if the dementia lags behind the motor symptoms.

PSP or CBD may present as dementia without motor abnormalities or as levodopa-responsive parkinsonism without incompatible signs and there may be no clinical way to correctly identify the disease until it progresses. Any patient with symmetric parkinsonian signs or where the lower body is more affected than the upper body may eventually develop a Parkinson-plus syndrome but this is neither sensitive nor specific.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree