Fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) is a noninflammatory, nonatherosclerotic arteriopathy of medium-sized vessels of unknown cause. Although it can affect any vascular bed, the renal and cervicocranial carotid and vertebral arteries are most commonly involved.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cervicocranial FMD is a rare condition, with one autopsy study citing an overall prevalence of 0.02%. Rates for renovascular FMD are higher, with prevalence estimates of up to 4% shown in several studies. In confirmed FMD cases, renal involvement is generally seen in up to 65% of cases, with cerebrovascular involvement in 25% to 30% of cases. In a series of 1,100 FMD patients, women were twice as frequently affected as men with Caucasians disproportionately affected. The mean age of diagnosis in patients with cerebrovascular involvement is 50 years, older than for renovascular involvement. Approximately 10% of cases are felt to be familial. Diagnosis is frequently delayed, with up to 9 years elapsing from initial symptoms to diagnosis.

PATHOBIOLOGY

There are three types of FMD, characterized by arterial layer of involvement: intimal fibroplasia, medial dysplasia, and adventitial fibroplasia. Intimal fibroplasia occurs in up to 10% of cases and results from accumulation of abnormal subendothelial mesenchymal cells, which project into the vessel lumen. This commonly results in areas of smooth, focal stenosis or long tubular stenosis. Adventitial fibroplasia, where the fibrous adventitia is replaced by collagen, is very rare.

Medial dysplasia is the most common, with three distinct subtypes recognized: medial fibroplasia, perimedial fibroplasia, and medial hyperplasia. Medial fibroplasia is the most common and accounts for up to 80% of cases.

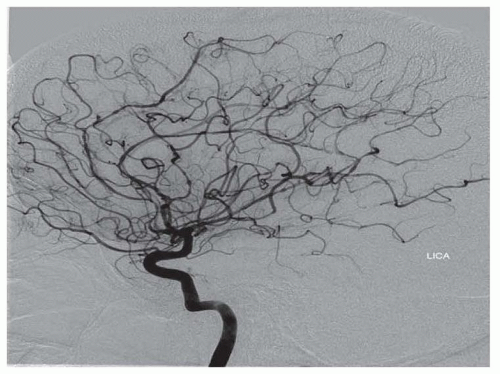

The main histologic hallmark is disruption of smooth muscle cells, which are replaced by fibroblasts and collagen. There is frequently secondary disruption of the internal elastic lamina, which may lead to aneurysm formation. The alternating areas of medial disruption give rise to the commonly seen “string of beads” radiographic appearance, where areas of stenosis are admixed with dilated areas that are of larger caliber than the original vessel. Perimedial fibroplasia results from abnormal collagen deposition between the media and adventitia, leading to areas of stenosis with preserved internal elastic lamina. Radiographic appearance may be similar to medial fibroplasia, but the “beads” are of smaller diameter than the original vessel.

Although the etiology is unknown, FMD is associated with a variety of diseases including alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, Marfan syndrome, and Alport syndrome. Given the female preponderance, hormonal links have been posited, although evidence is lacking. Ischemia at the level of the vasa vasorum has been suggested as a possible underlying factor, although this remains unproven.

CLINICAL FEATURES

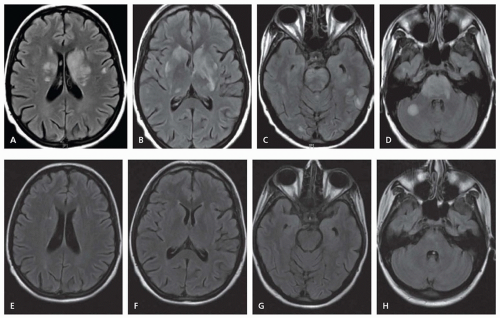

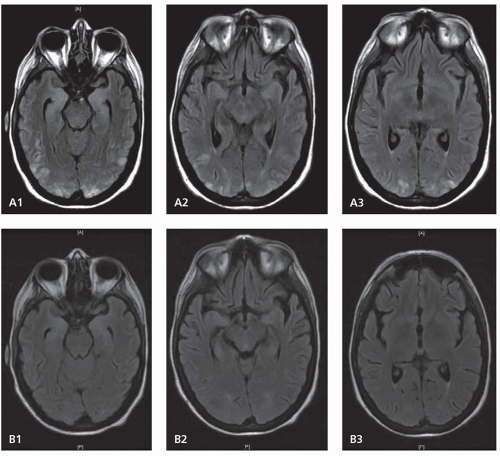

Cervicocranial FMD is frequently an incidental finding and rates of neurologic symptoms vary. Neurologic complications mainly arise due to ischemic or hemorrhagic symptoms that result from stenosis, thrombosis, dissection, or aneurysmal formation. Carotid-cavernous fistulas have also been described. Severe stenosis can cause distal hypoperfusion. Thrombotic occlusion of a stenotic vessel or distal embolism can lead to hemispheric ischemic symptoms. SAH can result from intracranial aneurysm rupture. Spontaneous cervical dissection can also occur, and headache, dizziness, carotidynia, pulsatile tinnitus, and Horner syndrome are all symptoms commonly seen with cervicocranial FMD. Dissection may be more common in Asian populations.