Fig. 14.1

Serotonin-producing PanNETs show different architectural features including trabecular (a) or acinar (b) patterns of growths, and some cases can present marked stromal fibrosis (c). Although serotonin-producing PanNETs are generally well differentiated, some cases can show poorly differentiated morphology including cell atypia with focal necrosis (d)

Tumors arising within the main pancreatic duct were reported as well differentiated and small ranging from 5 to 15 mm in size. They resulted in a localized stricture or stenosis of the duct, which, in turn, determined an upstream dilatation of the ducts associated with chronic obstructive pancreatitis [41, 43–46].

McCall and coworkers have reported that serotonin-producing PanNETs were more frequently associated with fibrosis than other PanNET types [45]. It is worth noting that serotonin-producing NETs arising in the small intestine produce several growth factors that stimulate fibroblast proliferation and function, resulting in marked stromal fibrosis [53–56]. However, it has been recently demonstrated that, conversely to ileal serotonin-producing NETs, serotonin-producing PanNETs do not express acidic fibroblast growth factor (aFGF) and express connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) at a low level [42]. These are well-known growth factors involved in tumor fibrosis development, and these findings suggest that stromal fibrosis observed in several serotonin-producing PanNETs may be due to different factors that have to be identified.

Most of reported serotonin-producing pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms were morphologically well differentiated, so they have to be considered as neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) according to the 2010 WHO classification [57]. However, since mitotic count and Ki67 index were not reported in several cases, the tumor grade of all published cases is not known. Among the 36 reported PanNETs for which the proliferative assessment was available, 25 (69.4 %) were G1 (grade 1) showing less than 2 mitoses × 10 HPF and less than 3 % of Ki67 proliferative index [42–46].

Immunohistochemical analyses have demonstrated that serotonin-producing PanNETs express general neuroendocrine markers, serotonin, and somatostatin receptor 2A (Fig. 14.2), while they generally lack the expression of pancreatic hormones (insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide) and gastrin. Interestingly, additional immunohistochemical investigations demonstrated that serotonin-producing PanNETs show a different immunophenotype with respect to intestinal serotonin-producing NETs. These differences include the lack of substance P and aFGF immunoreactivity; the lack of S100-positive sustentacular cells; the low expression of CDX2, prostate acid phosphatase, CTGF, and vesicular monoamine transporter 1 (VMAT1); and a strong expression of VMAT2 [42, 45]. These different immunohistochemical features suggest that serotonin-producing PanNETs are different from their intestinal counterparts, and this has also been demonstrated at the ultrastructural level. Indeed, tumor cells show ultrastructural features resembling those of the so-called “gastric-type” EC cells which differ from “intestinal-type” EC cells (Fig. 14.3) [42].

Fig. 14.2

Serotonin-producing PanNETs are strongly and diffusely positive for serotonin (a), vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2, b), and somatostatin receptor 2A (c)

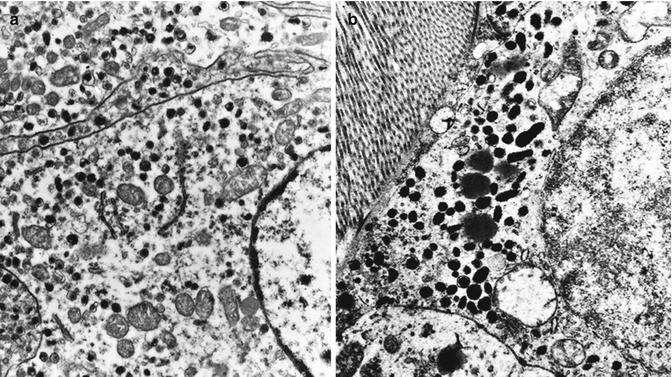

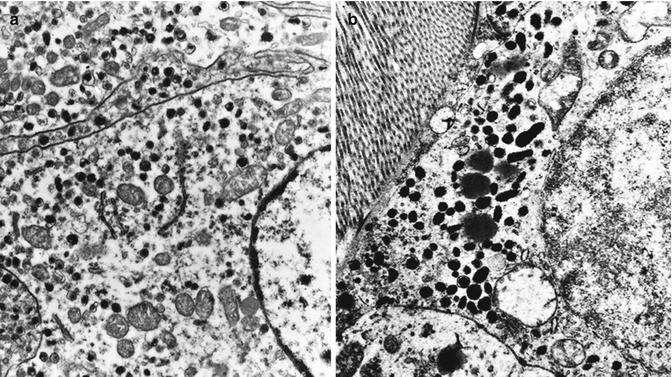

Fig. 14.3

At the ultrastructural examination, serotonin-producing PanNETs are well granulated and show small (mean size of 170 × 120 nm) pleomorphic round-ovoid secretory granules (a). EC cells of ileal neoplasms are very densely granulated showing larger (mean size of 380 × 140 nm) pleomorphic rodlike or biconcave secretory granules (b) (original magnification ×10,000)

Despite the various differences described above, a similar cytogenetic pattern of chromosome 18 has been demonstrated in both serotonin-producing pancreatic and ileal NETs [42]. Chromosome 18 deletions have been frequently found in ileal NETs and have also been described, although less frequently, in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms [58–60]. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis and progression of serotonin-producing PanNETs are largely unknown, this finding suggests that there is at least a common molecular alteration between pancreatic and ileal serotonin-producing NETs.

14.5 Prognosis

The overall survival of patients with serotonin-producing PanNETs is shown in Fig. 14.4a. The survival analysis of all cases reported in the medical literature shows that 60.5 % and 50.8 % of patients were alive 5 and 10 years after diagnosis, respectively. Patients with nonfunctioning neoplasms show a statistically significant better survival rate (p, 0.0029) than patients with functioning tumors associated with the carcinoid syndrome (Fig. 14.4b). In particular, 79.1 % and 69.3 % of patients with nonfunctioning serotonin-producing PanNETs were alive at 5 and 10 years after the diagnosis, respectively, showing a survival rate similar to patients with nonfunctioning neoplasms which accounts for 80 % at 5 years and 67 % at 10 years after diagnosis [50]. 34.9 % of patients with functioning serotonin-producing PanNETs were alive 5 years after diagnosis as compared to 35 % of patients with functioning ACTH-secreting PanNETs [61], 97 % with insulinomas [62], 72 % with gastrinomas [63], and 75.2 % with somatostatinomas [64]. 17.4 % of patients with functioning serotonin-producing PanNETs were alive 10 years after diagnosis as compared to 16.2 % of patients with ACTH-secreting PanNETs [61], 86 % with insulinomas [62], and 59 % with gastrinomas [63].

Fig. 14.4

(a) Overall survival of patients with serotonin-producing PanNETs. (b) Patients with nonfunctioning neoplasms (black line) show a statistically significant better survival rate (p, 0.0029) than patients with functioning tumors (dotted line) associated with the carcinoid syndrome

From these prognostic evaluations, it appears that nonfunctioning serotonin-producing PanNETs have a survival rate similar to that of nonfunctioning PanNETs, while functioning serotonin-producing PanNETs are aggressive neoplasms with a survival rate similar to that of other aggressive functioning neuroendocrine pancreatic neoplasms like ACTH-secreting PanNETs associated with Cushing’s syndrome.

References

1.

Oberdorfer S (1907) Karzinoid tumoren des dünndarms. Frankfurt Z Pathol 1:426–429

2.

Solcia E, Klöppel G, Sobin LH (eds) (2000) Histological typing of endocrine tumours. WHO International Histological Classification of Tumours, 2nd ed. Springer, Berlin

3.

DeLellis RA (2001) The neuroendocrine system and its tumors: an overview. Am J Clin Pathol 115(suppl):S5–S16PubMed

4.

Chetty R (2008) Requiem for the term “carcinoid tumour” in the gastrointestinal tract? Can J Gastroenterol 22:357–358PubMedCentralPubMed

5.

Osamura RY, Oberg K, Speel EJM et al (2004) Serotonin-secreting tumours. In: DeLellis RA, Lloyd RV, Heitz PU, Eng C (eds) World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of tumours of endocrine organs. IARC Press, Lyon, p 198

6.

7.

van Der Sluys Veer J, Choufoer JC, Querido A et al (1964) Metastasising islet-cell tumour of the pancreas associated with hypoglycaemia and carcinoid syndrome. Lancet 1:1416–1419CrossRef

8.

Gloor VF, Pletscher A, Hardmeier T (1965) Metastasierendes inselzelladenom des pancreas mit 5-hydroxytryptamin und insulinproduktion. Schwaiz Med Wonchenschr 94:1476–1480

9.

11.

Appleyard TN, Losowsky MS (1970) A pancreatic tumour with carcinoid syndrome and hypoglycaemia. Postgrad Med J 46:159–162PubMedCentralPubMedCrossRef

12.

Persaud V, Walrond ER, Jamaica K (1971) Carcinoid tumor and cystadenoma of the pancreas. Arch Pathol 92:28–30PubMed

13.

14.

Patchefsky AS, Gordon G, Harrer W et al (1974) Carcinoid tumor of the pancreas. Ultrastructural observations of a lymph node metastasis and comparison with bronchial carcinoid. Cancer 33:1349–1354PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree