Fig. 10.1

Functioning somatostatinoma characterized by a trabecular architecture (a) and showing somatostatin (b) and calcitonin (c) immunoreactivity (H original magnification ×400; immunohistochemistry original magnification ×200)

Fig. 10.2

Nonfunctioning somatostatin-producing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with a trabecular structure (a) (H&E, original magnification ×400) and showing somatostatin immunoreactivity (b) (immunohistochemistry original magnification; ×400). (c) Example of a nonfunctioning somatostatin-producing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor positive for somatostatin (d) showing an acinar structure resembling that of duodenal somatostatin-producing neuroendocrine tumors (H&E and immunohistochemistry; original magnification ×400)

By special stains, tumor cells are uniformly non-argentaffin and show argyrophilia only with the Hellerstrom-Hellman technique which is selective for somatostatin-producing cells [8].

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells are strongly positive for synaptophysin and with varying degree of immunoreactivity for somatostatin [43] (Figs. 10.1 and 10.2). Immunolabeling for chromogranin A, however, may be negative [23]. More than half of the tumors additionally exhibit scattered cells with immunoreactivity for other peptides such as pancreatic polypeptide (PP), insulin, glucagon, gastrin, adrenocorticotropin, and calcitonin [23, 43, 47]. As in other types of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, the transcription factor islet 1 gene product (ISL1) is also expressed in somatostatin-producing tumors [48]. In the series of Garbrecht et al., tumors with a gangliocytic appearance typically showed immunohistochemical positivity for somatostatin, VIP, and PP [23].

By electron microscopy, tumor cells contain two distinct populations of intracytoplasmic membrane-bound neurosecretory granules (Fig. 10.3). The majority of the secretory granules are large (range of diameter 250–450 nm), round, and moderately electron dense, resembling those of normal D cells. The second subset consists of smaller granules (range of diameter 150–300 nm), with dense cores surrounded by a thin peripheral halo [43].

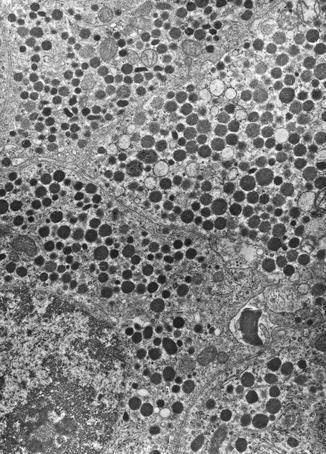

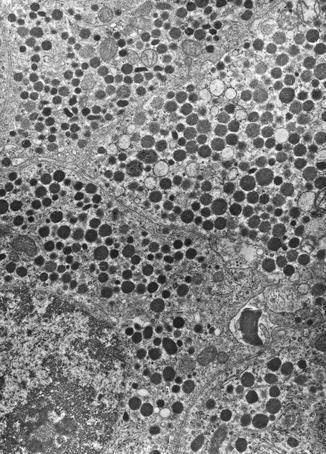

Fig. 10.3

Ultrastructural features of the functioning somatostatinoma showed in Fig. 10.1 containing numerous large, round, and moderately electron-dense membrane-bound secretory granules (original magnification ×10,000)

Because of the rarity of these tumors, there are only very few molecular data on somatostatinomas available in the literature. Recently, somatic and germline mutations in the HIF2A gene of patients with pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas associated with polycythemia, and in some of them also with somatostatinomas were described [49].

10.4 Clinical Diagnosis

The clinical features of the somatostatinoma syndrome include the classical triad of diabetes mellitus, gallstones, and steatorrhea [13, 25, 50]. Additional symptoms consist of hypochlorhydria, weight loss, and anemia [13, 16, 19, 22, 51].

The diagnosis of a “somatostatinoma” is confirmed by documentation of elevated plasma concentrations of somatostatin and the presence of the abovementioned somatostatinoma syndrome.

The normal plasma level of somatostatin is less than 100 pg/ml. Patients with a functioning somatostatinoma usually have very high levels of somatostatin. A mean of 15.5 ng/ml (range, 0.16–107 ng/ml) has been reported [52]. Mild elevations of somatostatin, however, may also occur in other endocrine disorders. The value of provocation tests, such as with tolbutamide, calcium, secretin, etc., has been debated but can be useful in some cases [53].

Tumor localization is usually accomplished by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a very sensitive method which may be combined with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) allowing preoperative diagnosis [54]. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS) using radiolabeled octreotide may also be useful in somatostatin-producing tumors [55] and may be helpful to identify clinically unsuspected extra-abdominal metastases. FDG-PET imaging has also been reported to be useful in detecting somatostatin-producing tumors, although its place in the diagnostic evaluation is uncertain [56].

10.5 Prognosis

The largest experience with these uncommon endocrine tumors estimates a 75.2 % 5-year overall survival, with 59.9 % of the patients with metastases and 100 % of the patients without metastases [7].

Acknowledgments

I thank Prof. S. La Rosa for providing the histological and EM pictures.

References

1.

3.

4.

Tomic S, Warner T (1996) Pancreatic somatostatin-secreting gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastases. Am J Gastroenterol 91(3):607–608PubMed

5.

Ghose RR, Gupta SK (1981) Oat cell carcinoma of bronchus presenting with somatostatinoma syndrome. Thorax 36(7):550–551PubMedCentralPubMedCrossRef

6.

7.

Soga J, Yakuwa Y (1999) Somatostatinoma/inhibitory syndrome: a statistical evaluation of 173 reported cases as compared to other pancreatic endocrinomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 18(1):13–22PubMed

8.

Dayal Y, Oberg K, Perren A, Komminoth P (2004) Somatostatinoma. In: DeLellis RA, Lloyd RV, Heitz PU, Eng C (eds) World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of endocrine organs. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 189–190

9.

10.

Luft R, Efendic S, Hokfelt T, Johansson O, Arimura A (1974) Immunohistochemical evidence for the localization of somatostatin–like immunoreactivity in a cell population of the pancreatic islets. Med Biol 52(6):428–430PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree