I. Dysplastic

II. Isthmic

A. Spondylolysis

B. Isthmus elongation

C. Acute fracture

III. Traumatic

IV. Degenerative

V. Pathologic

VI. Iatrogenic

According to their classification, the majority of slips belongs to the isthmic type in which an interruption (spondylolysis) or elongation of the pars interarticularis (isthmus) of the vertebral arch is present. The dysplastic spondylolisthesis develops due to congenital changes of the upper part of the sacrum and the vertebral arch of L5. Subluxation of the facet joints is always present in this form. True dysplastic spondylolisthesis is rare. Further types are traumatic spondylolisthesis in acute fractures, degenerative spondylolisthesis as a result of disc and facet joint degeneration in elderly people, and pathologic spondylolisthesis caused by infection or tumour destruction of parts of the vertebral arch [90, 149]. Iatrogenic spondylolisthesis may occur after excessive resection of posterior vertebral elements [149]. This classification has been criticised rightly for being inconsistent and mixing aetiologic (e.g. dysplastic) and anatomic (e.g. isthmic) terms. As its inventors already realised, the distinction between isthmic and dysplastic forms is not always possible. And no specific treatment guidelines are derived. To overcome these shortcomings recently improved classification systems have been proposed [71, 73].

The Marchetti-Bartolozzi classification (Table 24.2) has gained much popularity especially in North America [74]. It breaks spondylolisthesis down into two main aetiologic groups: developmental and acquired. For all developmental forms, the authors assume a more or less severe congenital dysplasia (i.e. weakness) in the posterior elements (“bony hook”) of the vertebra leading with time under physiologic loads to spondylolysis and/or spondylolisthesis. The developmental form is subdivided into high dysplastic and low dysplastic, each with spondylolysis or elongation of the pars. The acquired forms of spondylolisthesis are traumatic, post-surgery, pathologic and degenerative with their respective subgroups.

Table 24.2

Classification of spondylolisthesis

Developmental | Acquired |

|---|---|

High dysplastic | Traumatic |

With lysis | Acute fracture |

With elongation | Stress fracture |

Low dysplastic | Post-surgery |

With lysis | Direct surgery |

With elongation | Indirect surgery |

Pathologic | |

Local pathology | |

Systemic pathology | |

Degenerative | |

Primary | |

Secondary |

The classification proposed by Mac-Thiong and Labelle has its roots in the Marchetti-Bartolozzi classification. It was refined by adding criteria concerning the sagittal spino-pelvic balance and recommendations for operative treatment based on current practice [71].

A drawback of these newer classifications is that they are rather complex in view of daily clinical use. The distinction between different types is partly arbitrary and not always clear-cut. There are still “grey zones” [73], and the real benefit for clinical decision making is not obvious. The patient’s age, a very important factor, is neglected. And the treatment recommendations given for the different types of spondylolisthesis have not been verified yet prospectively in a sufficient number of patients.

Another new classification, designed especially for children and adolescents, was proposed by Herman and Pizzutillo [42]. It includes pre-spondylolytic stress reactions of the isthmus seen in single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It focuses on non-operative treatment. According to the inventors, its validation concerning treatment recommendations will take several years.

The degree of anterior translation as described by Meyerding is a commonly used classification system to describe the deformity and to assess for progression [80]. This classification divides the lower vertebral body into four parts to describe the percentage of slippage: grade I is <25 %, grade II is 26–50 %, grade III 51–75 % and grade IV 76–100 %. Grade V >100 % which is often used for spondyloptosis was not mentioned in Meyerding’s original publication.

In the author’s experience, for practical decision making at present, the essential factors are the degree of slip, the sagittal alignment (lordosis/kyphosis) at the level of the slip, patient’s age and symptoms. In this context, it is of secondary interest whether a slip is to classify, e.g. as dysplastic or not.

24.1.3 Natural History and Risk of Progression

The natural history of isthmic spondylolisthesis is benign in the majority of cases due to a tendency towards self-stabilisation of the affected segment [119, 141]. Despite that, isthmic spondylolisthesis is the most important cause of low-back pain and radiating leg pain in children and adolescents [62]. The average prognosis of the adult individual with isthmic spondylolisthesis concerning low-back problems and working ability does not differ from the rest of the population [7, 28, 38, 141]. There is no explanation yet why some people with spondylolysis or isthmic spondylolisthesis become symptomatic while the majority remains symptom free. As sources of pain the lytic defect itself, the intervertebral disc, the nerve roots and the ligaments are all possibilities [13, 83, 92, 114, 115, 145].

Spondylolysis may be present without vertebral slip. If the slipping occurs it happens mainly during the growth period and is usually mild [7, 123]. Participation in competitive sports does not seem to increase the risk for progression [87]. Risk factors for progression in young individuals are high degree of slip (>20 %) at admission and age before growth spurt [44, 123]. The trapezoid shape of the slipped vertebral body and rounding of the upper endplate of the sacrum in more severe slips are frequently interpreted as “dysplastic” changes and/or predictors of progression. They are, however, in most cases secondary changes. They express the severe slip; they do not predict it [7, 12, 27, 43, 61, 99, 123].

24.2 Clinical Presentation

24.2.1 Symptoms

Pre-school children are usually pain-free. In this young age group, the condition is mostly detected by chance or due to posture changes and/or gait abnormalities (see Sect. 24.4.4). In older children, the unset of the symptoms is often spontaneous. A history of sports activities is very common. Sometimes acute trauma is reported.

The leading symptom is low-back pain during physical activities as well as while standing and/or sitting for a longer period of time. The pain may radiate to the buttocks and to the posterior or lateral aspect of the thigh, seldom more distally to the lower leg, ankle or foot. In the severe slip (>50 %, Meyerding III and IV), gait disturbances, numbness, muscle weakness and symptoms of cauda equina compression may be present. There is, however, no direct relationship between severity of subjective symptoms and the amount of slip.

24.2.2 Physical Examination

In low-grade slips (Meyerding I and II), the patient’s gait and posture are usually normal unless radicular symptoms are present. The mobility of the lumbar spine is free or decreased due to muscle spasm and pain. Maximal extension may induce pain at the lumbosacral junction. There is local tenderness during palpation, and in many cases a step can be felt between the spinous processes at the level of the slip. Tightness of the ischiocrural muscles (hamstrings), typical for high-grade spondylolisthesis, is sometimes seen also in the symptomatic patients with a low-grade slip. Muscle strength, reflexes and skin sensation of the lower extremities are normal in the majority of patients.

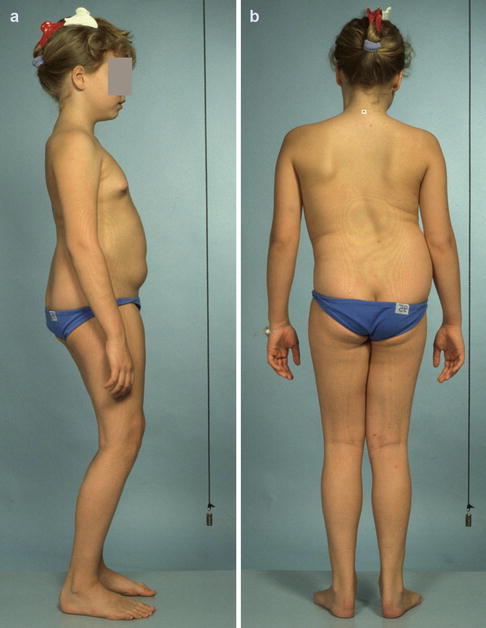

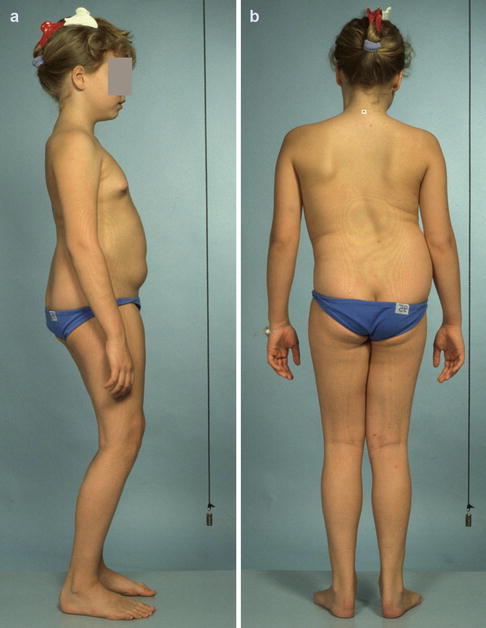

In a high-grade slip (Meyerding grades III–IV slips and spondyloptosis), the clinical picture is very variable despite the severe local malalignment of the spine seen in the radiograph. In many cases, the patient’s posture is disturbed in a typical way (Fig. 24.1): The sacrum is in vertical position due to retroversion of the pelvis. There is a short kyphosis at the lumbosacral junction and a compensatory hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine usually reaching up into the thoracic region [76]. The spine is scoliotic and often out of balance in the frontal as well as in the sagittal plane. The patient is unable to fully extend hips and knees during standing, and she/he walks with a typical pelvic waddle. In those patients the hamstrings are always extremely tight [100]. Signs of neural impairment (muscle weakness, disturbances of skin sensation, incontinence) may be present. Some patients look clinically normal and show, e.g. only some milder hamstring tightness. Astonishingly, even in severe slips objective neurologic findings are rare. Many patients are subjectively almost free of pain symptoms despite significant posture changes and hamstring tightness.

Fig. 24.1

(a) Typical clinical appearance of a symptomatic 11-year-old girl with high-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis. Vertical position of the sacrum due to retroversion of the pelvis, the patient is forced to stand with hips and knees flexed. (b) The spine is out of coronal balance, there is a secondary “sciatic” lumbar scoliosis

In some patients lumbar or thoracolumbar scoliosis is seen as a secondary phenomenon to spondylolisthesis. “Sciatic” forms (mainly in high-grade slips) are due to pain and muscle spasm and disappear usually after relieve of symptoms. Structural (“olisthetic”) curves caused by rotational displacement of the slipped vertebra have to be followed closely and lumbosacral fusion operation is indicated if progression occurs [121]. Thoracic scoliosis in a patient with lumbar spondylolisthesis is assessed as a separate entity and treated according to the guidelines for scoliosis management.

24.3 Imaging

24.3.1 Plain Radiographs

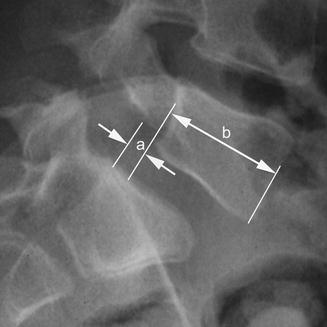

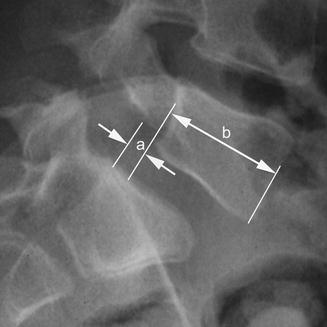

Plain radiographs (PA and lateral) of the lumbar spine in standing position focused on the lumbosacral junction should be obtained. The images show the alignment of the lumbar spine and the true amount of vertebral slip if any. In most cases the lateral projection will also reveal the spondylolysis (Fig. 24.2). The use of traditional oblique plain radiographs to verify a lysis not visible in the standing lateral view is obsolete. At the author’s institution, the slip is measured according to Laurent and Einola as the quotient between the sagittal slip and the sagittal length of the slipped vertebral body expressed in per cent (Fig. 24.3) [61]. This method allows for an exact measurement to detect and document also smaller changes especially if one thinks about follow-up radiographs to identify slip progression during growth. The sagittal lumbosacral alignment (lordosis/kyphosis) is assessed from the same radiograph and measured as the angle between the posterior border of the first sacral vertebral body and the anterior or posterior border of the fifth vertebral body (Fig. 24.4). Long-standing films of the whole spine in two planes are taken if the spine is clinically significantly out of balance and/or if scoliosis is present.

Fig. 24.2

Spondylolysis (arrow) and a low-grade L5 slip on a standing lateral radiograph

Fig. 24.3

Calculation of the percentage of vertebral slip according to Laurent and Einola [73]. Slip [%] = a/b × 100

Fig. 24.4

Measurement of lumbosacral kyphosis as the angle (k) between the posterior border of S1 and the posterior (or anterior) border of L5

24.3.2 Functional Radiographs

Flexion-extension radiographs have been traditionally used in order to detect possible “instability” in the olisthetic segment. They are not in use anymore as we could not see any value for decision making concerning the patient’s treatment. However, in high-grade slips with lumbosacral kyphosis, a lateral hyperextension radiograph in supine position is taken preoperatively (Fig. 24.5). It demonstrates the reducibility of the slipped vertebra to judge whether the disc space below the vertebra will be accessible during a planned anterior procedure without the need for instrumented reduction.

Fig. 24.5

(a) Patient positioning for the lateral supine hyperextension radiograph of the lumbosacral junction in high-grade slips. (b) Standing lateral radiograph shows significant lumbosacral kyphosis. (c) On the supine hyperextension radiograph of the same patient, a marked decrease of the kyphosis is visible

24.3.3 Computed Tomography (CT)

In most cases the lysis can be easily seen from the standing lateral radiograph. If in doubt, a CT image with the gantry tilted to obtain slices in the longitudinal direction of the isthmus should be taken. It is the most reliable imaging mode for demonstrating the spondylolysis (Fig. 24.6). CT is also very valuable to assess possible healing of the defect [5, 37].

Fig. 24.6

(a) Isthmus CT-image of a 10-year-old boy, “early-traumatic” spondylolysis. (b) Isthmus CT-image of an 11-year-old girl, “atrophic” spondylolysis. (c) Isthmus CT-image of an 14-year-old boy, “hypertrophic” spondylolysis

24.3.4 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Increasingly, MRI is used as a primary imaging mode for children with low-back pain. Especially in young athletes increased signal intensity is seen frequently in the area of the isthmus or the pedicles. This is interpreted as a stress reaction. Its importance and natural history are unclear so far. There are difficulties to distinguish these stress reactions from true spondylolysis in MRI. Prospective studies are needed to clarify this phenomenon.

In low-grade slips without neurologic signs, there is no rational indication for MR imaging. MRI is indicated in cases with neurologic symptoms, cauda equina syndrome, or if disc herniation is suspected. It is helpful to demonstrate the shape of the spinal canal, the intervertebral foramina, and possible compression of neural structures (Fig. 24.7).

Fig. 24.7

(a) Midsagittal lumbar MR image in high-grade spondylolisthesis. The central spinal canal is narrowed; the L5-S1 disc is severely damaged, (b, c) Right and left parasagittal lumbar MR images in high-grade spondylolisthesis. The L5 roots (arrow) are caught between the pedicle and the disc

MR also allows to assess the condition of the intervertebral discs at and adjacent to the olisthetic segment. The disc below the slipped vertebra is often pathologic already in young individuals regardless of whether they do have pain symptoms or not. Dehydration of the adjacent disc above the slipped vertebra is relatively common in symptomatic patients [114, 115]. As the clinical relevance of disc dehydration seen on MR images of young persons is unclear, MR is not of value for clinical decision making in spondylolisthesis in this respect [105].

Symptomatic disc herniation at the level of the slip is very rare in patients with isthmic spondylolisthesis [101].

24.3.5 Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT)

The SPECT technique is nowadays often used for evaluation of low-back pain especially in young athletes. It shows increased uptake in stress reactions, microfractures and fractures. It allows differentiating chronic spondylolysis (pseudarthrosis) from fresh, active lesions which theoretically should have a higher healing potential. However, its predictive value concerning healing of the spondylolysis has not been established yet [8, 19, 81, 133, 134].

24.4 Treatment

The benign natural history of the condition should always be kept in mind when weighing the necessity for treatment and the treatment options. The parents are usually very worried after learning that there is something “broken” in the lower back of their child. In every case, it is very important to explain the basically benign nature of the course to the patient and to the parents. In many cases symptoms resolve after several months without any special treatment. At the same time it should be made clear that the condition may not be ignored either. Follow-up for a certain period of time is necessary to act appropriately if significant progression occurs. The parents should also be informed that effective treatment is at hand if prolonged severe subjective symptoms are present or marked slip progression is seen.

The only case for immediate decision towards active intervention is a high-grade slip with lumbosacral kyphosis and/or a significant neurologic deficit.

24.4.1 Observation

Rapid growth and a slip of more than 20 % have been identified as risk factors for progression [43, 123]. Therefore, children before or during the growth spurt have to be checked at regular intervals until the rapid growth is over [146, 123]. Plain standing lateral radiographs of the lumbar spine are obtained every 6–12 months depending on the degree of slip at admission and the age of the patient. There is no need for restriction of physical activities during follow-up. At the end of the observation period, the patient and the parents should be assured that there are no restrictions in view of future sports activities or choice of occupation.

24.4.2 Non-operative Treatment

Symptomatic spondylolysis or low-grade spondylolisthesis is primarily typically treated non-operatively by decreasing the level of physical activities, strengthening of back and abdominal muscles, and sometimes a brace [6, 23, 72, 131]. Patients participating regularly in sports are advised to modify their training program to avoid pain-causing exercises. But there is no reason to stop all physical activities. According to the literature, the functional outcome after brace treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes is good or excellent in 80 % or more. Healing of the defect can be demonstrated radiologically in 16–57 % of involved patients. Unilateral defects seem to heal more often than bilateral defects as do defects at L4 in comparison to L5 defects. There is no correlation between healing and good clinical outcome. Neither the efficacy of bracing nor the predictive value of increased activity of the lysis in SPECT scans can be demonstrated definitely as there are no prospective comparative studies available [7, 30, 81, 109, 131, 133]. Klein et al. presented a meta-analysis of 15 observational studies (665 patients) on non-operative treatment for spondylolysis and Grade I spondylolisthesis [54]. They concluded that non-operative treatment is successful in 83.9 %, bracing has no influence on the result, and most of the defects do not heal.

24.4.3 Operative Treatment

The data on operative treatment of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in children (up to 12 years of age) are very sparse due to the fact that in the vast majority of reports children and adolescents are treated as one group. The impact of patients’ age at operation on the results is usually not analysed. No randomised trials comparing operative treatment to natural history are available thus far. In his retrospective long-term follow-up study, Seitsalo investigated 149 patients with low-grade slips after a mean follow-up of 13.3 years [119]. Seventy-two patients (mean age 13.8 years, mean slip 16.2 %) had conservative treatment or no treatment at all while 77 patients (mean age 14.6 years, mean slip 16.6 %) were treated by uninstrumented posterior or posterolateral fusion. At follow-up, 75 % of the conservatively treated patients and 87 % of the operatively treated patients were free of pain. None of the primarily conservatively treated patients had an operation at a later date. In the conservative group, 6 of 72 patients (8.3 %) patients and 4 of 77 (5.2 %) patients in the operative group reported decreased working ability. In a recent long-term cohort study, Jalanko et al. compared the results after fusion surgery between children operated on before onset of the pubertal growth spurt (females <12.5 years old, males <14.5 years old) and adolescents [47]. They could not find any differences of clinical importance in patients’ functional, radiographic and health-related quality of life outcomes between the two age groups, neither for low-grade nor for high-grade slips.

The indication for operation in children and adolescents depends on the amount of slip (high-grade or low-grade), the age of the patient (before, during or after the growth spurt), and the clinical signs and symptoms. Neurologic symptoms (cauda equina syndrome, peroneus paresis) are a clear indication for operation. However, those occur very rarely even in high-grade slips. The most common reason for operation in low-grade slips is pain not responding to non-operative measures. In children with a slip of 50 % or more, operation is recommended also to prevent further progression even if the patient has only minor symptoms or no symptoms at all. Operation should also be considered in a very young patient with a slip of over 20 % if progression occurs during follow-up.

The choice of the operative technique depends on the percentage of slip and/or lumbosacral kyphosis and on the personal experience and preferences of the surgeon. Table 24.3 represents the recommendations developed at the author’s institution. It can be used as a guideline for decision making. The listed numbers for slip percentages and degrees of lumbosacral kyphosis are not based on scientific evidence. They mark a smooth transition which cannot be defined with mathematical accuracy. The final decision is always made according to the individual situation of the patient taking into consideration patient’s stage of skeletal maturity, gender, individual anatomic features of the slip, ability to co-operate, patient’s and parents’ hopes and desires, and, last but not least, the surgeon’s personal experience.

Table 24.3

Management of isthmic spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents

Slip (%)a | Symptoms | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

0–25 | No | Follow-up during growth |

0–25 | Yes | Non-operative Operativeb Uninstrumented posterolateral fusion |

>25–50 | Yes/no | Consider post-lat fusion before growth spurt |

>50 L-s kyphosis <20° | Yes/no | Uninstrumented anterior fusion |

>50–90 L-s kyphosis >20° | Yes/noL-s kyphosis | Uninstrumented anterior/posterior fusion |

>90–100 (ptosis) | Yes/no | Partial reduction or resection + |

Instrumented anterior/posterior fusion |

24.4.3.1 Spondylolysis and Low-Grade Slip (≤50 %, Meyerding I and II)

Uninstrumented segmental posterolateral fusion in situ using autogenous bone from the posterior iliac crest is the method of choice for cases with a percentage of slip up to 50 % (Fig. 24.8). The operation is performed through the bilateral paraspinal muscle split approach as recommended by Wiltse [146, 147]. The segment above the slipped vertebra is usually not included into the fusion even if the disc shows signs of dehydration in MRI. The patient is mobilised 1–2 days after the operation wearing a soft brace for 3 months’ time. Sports activities are forbidden for 6–12 months depending on the radiologic development of the fusion. There are no restrictions of physical activities after solid bony healing. The method is very safe and effective. There are no specific complications. In this young age group it leads to bony fusion in 80–90 %. Subjective results and functional outcome are good or satisfactory in 82–96 % of the patients [62, 65, 116, 117, 126]. A recent long-term study in 107 children and adolescents with a mean age at operation of 15.9 years (range, 8.1–19.8) and a mean follow-up of 20 years has proven the lasting effectiveness and reliability of this method [58]. The mean Oswestry Disability Score [25] was 7.6 (range, 0–68) at last follow-up. It was in the normal range (0–20) in 100 out of 107 patients (93 %). Six (6 %) out of 107 patients had an Oswestry score of 20–40 (moderate disability); one patient had a score of 68 (crippled). Pseudarthrosis (17 % after posterolateral fusion) and adjacent disc degeneration on plain radiographs (12 %) did not correlate with poor outcome. The Scoliosis Research Society outcome instrument [35] yielded a mean of 94.0 points (range, 44–114 points) at follow-up [40]. Degenerative changes in MRI at follow-up did not have any significant influence on patients’ outcome [105].

Fig. 24.8

Uninstrumented posterolateral fusion for symptomatic low-grade slip in a 12-year-old male. (a) L5 spondylolysis at 8 years of age. (b) tanding lateral radiograph at 12 years of age. Then slip has progressed. The patient suffers from low-back pain and left leg pain. (c) On right parasagittal MR image, the right L5 nerve root (arrow) is free on MRI. (d) On left parasagittal MR image, compression of the left L5 nerve root (arrow). (e) Plain AP radiograph 4 years after posterolateral fusion without decompression. Note bilateral mature fusion mass (arrows). (f) Standing lateral radiograph 4 years postoperatively. Minimal progression of the kyphosis. The patient is free of symptoms

In low-grade slips, decompressive laminectomy is indicated in young patients only in rare cases with true impingement of neural structures. However, this has not been seen by the author in a low-grade slip during a period of over 30 years. Pseudoradicular symptoms (radiating pain to the posterior aspect of the thigh) and hamstring tightness resolve without laminectomy due to stabilisation of the segment by fusion. If decompression is performed during growth segmental fusion has to be added always to prevent subsequent progression of the slip [95].

The use of instrumentation has not been shown to give any advantages in low-grad slips in this age group. Nor is there any reason for reduction of low-grade slips. The author agrees fully with this statement published by Wiltse and Jackson in 1976 [146]. Internal fixation, with or without reduction, is connected with longer operation time, more severe muscle trauma, an increased risk of complications, and higher costs. It would probably increase the fusion rate. But the disadvantages mentioned above would not countervail this, as pseudarthrosis does not have a measurable negative effect on the outcome in this group of patients [58, 65, 119, 124].

In cases of spondylolysis without a slip or with a slip of less than 25 %, the direct repair of the isthmic defect is recommended by some authors reporting favourable results using different methods of internal fixation (screws, cerclage wire, butterfly plate, hook plate, pedicle screws and rods) [16, 33, 48, 51, 67, 86, 91]. Several authors reported favourable outcome especially in younger patients [14, 39, 46, 91]. There are no series published dealing exclusively with children. At the author’s institution Scott’s wiring technique with autologous bone grafting has been used [91]. For postoperative treatment a plastic TLSO was applied for 3–6 months. In a comparative study in children and adolescents, the results after mid-term and long-term follow-up were very good in the majority of cases, but not better than the results of uninstrumented segmental fusion. Thus, the benefit from saving the lytic-olisthetic motion segment could not be demonstrated so far [116, 117]. At present, the direct repair is used by the author only in cases of spondylolysis or minimal slips in the segments above L5.

24.4.3.2 High-Grade Slip (>50 %, Meyerding III and IV)

If the slip approaches 50 % the biomechanical situation changes profoundly with far reaching consequences for the sagittal alignment of the entire spine [66]. The physiologic lumbosacral lordosis decreases and, dependent of the amount of displacement, a kyphosis develops due to absence of anterior support for the slipping vertebra (Fig. 24.9). In the growing patient, this kyphotic deformity has a risk for progression in almost 100 %. Operation should be considered even in patients with minimal subjective symptoms or no symptoms at all [146]. There is no data showing that non-operative measures (exercises, bracing) or restriction of sports activities would stop the progression. One should not wait and see too long. Proceeding progression makes the necessary operation technically more difficult, increases the risk of complications, and leads possibly to an inferior result. It has, however, to be noted that in some cases even patients with high-grade slips or even spondyloptosis remain subjectively symptom-free. The author agrees with Bridwell that there is no “right way” to treat all high-grade slips [15]. But overtreatment for the sake of radiologic correction should be avoided. The methods applied should be assessed critically for their benefit for the patient in the long run in terms of clinical outcome and function.

Fig. 24.9

Radiographs demonstrating changes of lumbosacral alignment during slip progression. Standing lateral radiographs of a female patient at 6 years of age (a), 11 (b) and 16 (c) years show marked loss of the physiologic L5-S1 lordosis during slip progression. In another female patient, rapid deterioration of the sagittal alignment from 2° of lordosis (d) to 33° (e) of lumbosacral kyphosis within 18 months time

A considerable variety of methods for operative treatment of high-grade slips has been published: uninstrumented posterior or posterolateral fusion from L3 or L4 to S1 [34, 41, 45, 59, 65, 106, 122, 146], uninstrumented anterior interbody fusion [41, 102, 103, 136], uninstrumented combined fusion [57], uninstrumented posterolateral fusion L4-S1 and anterior fusion L5-S1 with cast immobilisation after preoperative gradual conservative reduction [59, 138], uninstrumented posterolateral fusion L3 or L4 to S1 with postoperative cast reduction [17], anterior reduction with anterior screw fixation and interbody fusion, posterior pedicle screw reduction with or without decompression and posterior or combined fusion using bone graft or cages [24, 77, 84, 88, 102, 103, 108, 110] or the Bohlman technique utilising a transsacral fibular strut graft [10, 36, 128], or a special titanium cage [2, 127], and anterior and posterior reduction with decompression, and double-plating [139].

According to Bradford, the goals of treatment for high-grade spondylolisthesis are to prevent progression, to relieve pain, to improve function and to reverse the neurologic deficit if there is any [13]. These goals can be achieved in the vast majority of cases safely by in situ fusion which wrongly is of bad repute. The reason for the negative attitude of many surgeons towards in situ fusion seems to be that many of them have seen symptomatic adult patients with a high-grade slip up to spondyloptosis who had a posterior or posterolateral “in situ” fusion of a more or less severe slip as teenagers. Usually, in the early years after the primary operation, they were symptom free. But with time, posture deteriorated and symptoms reappeared, sometimes they became even worse than before the operation. When analysing the radiographs, one sees that slow progression of the slip and the kyphosis happened over the years despite a solid-looking fusion mass. Retrospectively, one can say that although in situ fusion was attempted it was not achieved. Several of such cases with slow progression after posterior or posterolateral so-called in situ fusion L4 to S1are are shown in the very instructive papers by Taillard and Burkus et al. [17, 134]. The cause for the failure is misunderstanding of the biomechanics of a high-grade slip which in fact is a progressive kyphosis. Anterior bony support is insufficient or missing totally. The disc below the significantly slipped vertebra is always severely damaged. The disk will degenerate further and atrophy due to loss of functional motion after fusion. This all together induces increasing flexion moments on the posterior fusion mass which will bend and elongate. It must be stressed here that in the author’s language successful in situ fusion does mean that a solid bony fusion is achieved and even after long-term follow-up the position of the fused vertebra is not significantly worse than before the operation.

Biomechanically, the most reasonable procedure to stop the progression of a kyphotic deformity is to provide anterior support. This is the rationale for anterior fusion. At the author’s institution, uninstrumented anterior interbody fusion in situ without decompression is the method of choice for high-grade slips with no ore minimal (up to 10–20°) lumbosacral kyphosis (Fig. 24.10). The operation is performed through a transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approach using two to three autogenous tricortical iliac crest grafts. Uninstrumented combined anterior and posterolateral fusion in situ without decompression is preferred for slips with greater lumbosacral kyphosis (more than 20°). Combined fusion has been shown to be more effective in preventing the postoperative progression of the lumbosacral kyphosis, i.e. to achieve a true and lasting in situ fusion without late deterioration [41, 106]. Using this technique there is no need to include more than the olisthetic segment into the fusion. After anterior or combined procedures the patient is mobilised at the second or third postoperative day wearing a plastic TLSO for 3–6 months. Hamstring tightness disappears and spinal balance is regained within a few weeks although no decompression has been performed (Figs. 24.11, 24.12, and 24.13). The clinical short- and mid-term results of anterior and combined fusion in the severe slip are comparable to the results of posterior or posterolateral fusion [49, 59, 64, 122, 125, 136]. In a recent long-term follow-up study (67 patients, slip 50–100 %, mean age at operation 14.4 years, range 8.9–19.6, follow-up of 10.7–26 years.), the outcome after three different uninstrumented in situ fusion techniques (posterolateral, anterior, combined) without decompression was compared. At final follow-up, 14 % in the posterolateral and in the anterior fusion group reported low-back pain at rest often or very often, but none in the circumferential fusion group. The mean Oswestry index was 9.7 (0–62), 8.1 (0–32) and 2.3 (0–14) respectively, indicating combined fusion being slightly but not significantly superior. Radiographs showed some progression of the mean lumbosacral kyphosis during follow-up in the posterolateral and in the anterior only fusion group. No progression of the lumbosacral kyphosis was detected after combined fusion [106]. A comparison of the three groups using the Scoliosis Research Society questionnaire yielded the same kind of results with a slightly better outcome in the circumferential fusion group [40, 57]. It has, however to be noted that those patients are still in their thirties. And no data is available showing what happens when they reach midlife and seniority.

Fig. 24.10

Uninstrumented anterior in situ fusion without decompression for high-grade slip in an 11-year-old boy. Preoperative photographs (a–c) show typical posture changes. (a) The spine is slightly out of balance to the right. The spine appears to be lordotic. (b) he lordosis of the thoracolumbar spine is clearly seen. Note pelvic retroversion and positive sagittal balance. (c) C) Forward bending is restricted due to hamstring tightness preventing anterior rotation of the pelvis. (d) D) Eleven years postoperatively, the patient is free of symptoms. The spine is balanced in the coronal plane. (e) The sagittal profile is normal. (f) Full forward bending is possible. Hamstring tightness has resolved. (g) G) Preoperative standing lateral radiograph showing L5 slip of 66 % and a lumbosacral kyphosis of 18°. (h) At follow-up 11 years postoperatively, standing lateral radiograph shows solid anterior fusion. No progression of the deformity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree