CURRENT DEFINITION OF STEREOTYPY

Stereotypies are complex movement disorders commonly defined as “involuntary or unvoluntary [defined as a response to or as a result of an inner stimulus]… coordinated, patterned, repetitive, rhythmic, purposeless but seemingly purposeful or ritualistic movement, posture, or utterance” (1) that is at the expense of other voluntary behavior or movements, despite a normal level of consciousness. They can also interfere with learning (2). The most common examples include repeated head nodding, body rocking, head banging, hand flapping or waving, repetitive finger movements, picking at the skin, lip smacking or pursing, chewing movements, pacing, grunting, or humming (Table 22.1).

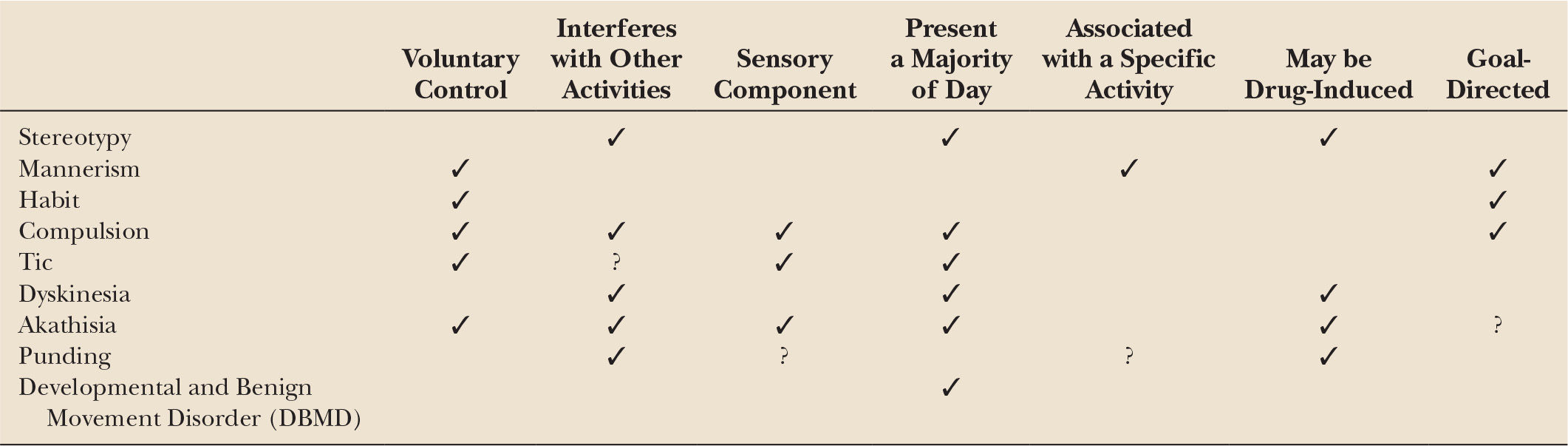

While helpful, this definition makes the differentiation of stereotypies from other motor phenomenology such as tics, dyskinesias, and compulsions very difficult (Table 22.2). At times, stereotypies can be difficult to distinguish from perseveration, although some use the term “perseveration” to refer to the mental aspect of these activities (3). Ridley and colleagues suggested that perseveration should refer to repetitive actions, but the term “stereotypy” should be used when referring to “excessive” repetitive actions (3). In addition to motor or phonic classifications, stereotypies can also be classified according to complexity (simple, complex) or the predominant region of involvement (for example; orobuccolingual, truncal, hand, leg). The movements may also be defined based on the setting in which they occur, or according to the underlying diagnosis. For example, drumming of the fingers may be considered a habit of a “normal person” but may be considered a compulsion, stereotypy, or tic in someone with schizophrenia, mental retardation, obsessive–compulsive disorders (OCDs), or Tourette’s syndrome (4). Nonetheless, the term “stereotypy” is generally reserved as a descriptor rather than an etiologic identifier. The lack of well-defined terminology has resulted in an ineffective classification of movements adding to the complexity of this topic. Better characterization and taxonomy can lead to better clinical utility, better recognition, and more appropriately directed therapies. More recently, Edwards and colleagues have suggested the following definition: “a non–goal-directed movement pattern that is repeated continuously for a period of time in the same form and on multiple occasions, and which is typically distractible” (5).

| Common Stereotypies |

• Head: Nodding, shaking, banging, posturing

• Mouth/face: Lip movements, tongue movements, grimacing, biting, smiling/frowning, bruxism, spitting

• Vocalizations: Snorting, blowing, hissing, screaming, whistling, grunting

• Upper extremities: Finger movements, arm flapping, hand rubbing, touching other parts of body, hair twirling or pulling, self-hugging

• Trunk: Rocking, swaying, pelvic thrusting, twisting

• Lower extremities: Jumping, squatting, sitting/arising, walking in back and forth or in circles/patterns

• Other: Self-injurious behavior, opening/closing doors

| Terms Often Used Interchangeably with Stereotypy |

Repetitive movements

Dyskinesias

Akathisia

Compulsions

Tics

Complex motor tics

Mannerisms

Compulsions

Restlessness

Punding

The new ICD-10 criteria (6) list “Stereotypic movement disorders (F98.4)” under “Other behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence,” and define it as follows:

“Voluntary, repetitive, stereotyped, nonfunctional (and often rhythmic) movements that do not form part of any recognized psychiatric or neurological condition. When such movements occur as symptoms of some other disorder, only the overall disorder should be recorded. The movements that are of a non self-injurious variety include: body-rocking, head-rocking, hair-plucking, hair-twisting, finger-flicking mannerisms, and hand-flapping. Stereotyped self-injurious behaviour includes repetitive head-banging, face-slapping, eye-poking, and biting of hands, lips or other body parts. All the stereotyped movement disorders occur most frequently in association with mental retardation (when this is the case, both should be recorded). If eye-poking occurs in a child with visual impairment, both should be coded: eye-poking under this category and the visual condition under the appropriate somatic disorder code.”

This defines stereotypy as a primary diagnosis and excludes other diagnoses such as abnormal involuntary movements, movement disorders of organic origin, nail-biting, nose-picking, stereotypies that are part of a broader psychiatric condition such as schizophrenia, thumb sucking, tic disorders, and trichotillomania.

PHYSIOLOGIC OR PRIMARY FORMS OF STEREOTYPY

Physiologic forms of stereotypies generally occur as part of normal development; they follow a typical course and largely disappear over time (5). Many stereotyped behaviors are defined as normal or abnormal based on the frequency of the movements, the situation in which they occur, and the degree to which they interfere with normal functioning, as well as the presence or absence of any other underlying pathology. Among normal children, approximately 20% demonstrate some form of stereotypy, typically before the age of three (7). The movements typically last seconds to minutes and can occur frequently throughout the day or during specific situations such as periods of stress, excitement, boredom, or fatigue. In younger individuals, this may include thumb or hand sucking, head or body rocking, or arm flapping. In older children, this may include finger or toe tapping, hair twirling, or bouncing or adducting–abducting the legs. Generally, these are not indicative of any underlying or impending pathology, although there are some reports that a significant percentage of normally developing children with such motor stereotypies will continue to exhibit some form of the activity several years later (8). One review of 40 normally developing children, aged 9 months to 17 years, with complex upper extremity stereotypies demonstrated that movements will nearly always be suppressed on cue. Additionally, a quarter of these children met criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and a fifth had a learning disability (9). In otherwise normal individuals, many of these repetitive movements are under conscious control (and thus not involuntary), do not interfere with normal function, and thus are not considered pathologic.

PATHOLOGIC FORMS OF STEREOTYPY (Table 22.3)

Stereotypies are often seen as features of a variety of disorders, most commonly mental retardation, autism spectrum disorders, psychoses, and in those who are congenitally blind or deaf. One study reports that as many as 34% of institutionalized nonambulatory persons with mental retardation exhibited at least one type of stereotypy (10).

| Etiologies of Stereotypy |

PHYSIOLOGIC

Primary

• No history of developmental delay, psychiatric disorder, or other secondary cause

Secondary

• Developmental delay/mental retardation

• Autism/autism spectrum disorders (including Rett’s syndrome)

• Basal ganglia lesions

• Obsessive–compulsive disorder

• Postinfectious disorders

• Paraneoplastic diseases

• Psychiatric diseases

• Schizophrenia

• Drug-induced movement disorders

• Tardive dyskinesia

• Akathisia

• Sensory deprivation or confinement

• Psychogenic disorders

• Neurodegenerative disorders

• Wilson’s disease

• Lesch–Nyhan

• Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation (NBIA)

• FTD

• Neuroacanthocytosis

Autism spectrum disorders, a subset of pervasive developmental disorders, encompass a wide variety of developmental disabilities that are characterized by poor social skills and attachment difficulties as well as impaired communication, cognition, and interaction with the world around them (11). Typically, motor development is thought to be normal, although many studies show impaired fine and gross motor skills (12,13) in addition to the presence of stereotypies. Common stereotypies seen include “facial grimacing, staring at flickering light, waving objects in front of the eyes, producing repetitive sounds, arm flapping, rhythmic body rocking, repetitive touching, feeling and smelling objects, jumping, walking on toes, and unusual hand and body postures” (14). There are several subtypes of autism, including Asperger’s, fragile X syndrome, and Rett’s syndrome. Asperger’s is one of the most common types of autism, often considered a milder variant, and is characterized by social isolation and difficulties with nonverbal communication but relatively preserved cognitive and language development. Fragile X syndrome, the most common cause of mental retardation in boys, causes intellectual disability, specific physical characteristics, and a variety of behavioral and learning difficulties. Self-rubbing, body movements (i.e., rocking, spinning), repetitive hand movements, and manipulating objects are typical manifestations (15,16). Rett’s syndrome is a disorder limited almost exclusively to females. Normal development is seen until the age of 6 to 18 months at which time a regression of language and motor skills is observed as well as stereotypic hand movements such as hand wringing or washing, clapping, and body rocking. Other movement disorders such as parkinsonism and dystonia may also occur.

Lesch–Nyhan syndrome is an X-linked disorder caused by abnormal purine metabolism. Patients exhibit severe mental retardation, dystonia, and stereotyped self-injurious behavior such as biting their lips, arms, or fingers, or scratching until blood is drawn often requiring restraints or extreme measures to reduce the risk of serious injury, including pulling teeth (17).

Sensory deprivation, including congenital blindness and/or deafness, is another common instigator of stereotypic behaviors. In those with visual impairment, the “oculodigital sign” (eye rubbing or poking) is common. This is thought to represent self-stimulatory behavior that produces pressure phosphenes (flashes of light induced by pressure, movement, or sound, not light). It is commonly described in children with very poor vision, such as in those with Leber’s congenital amaurosis (18). Other common movements include rocking, as seen in several well-known musicians. In those with hearing impairment, rocking is also often seen, but there is less incidence of self-injurious behavior (19).

Numerous stereotypic behaviors have been described in schizophrenics, most commonly in the catatonic subtype. Catatonia is typically associated with akinesia, abnormal, prolonged postures, and mutism (20). In the absence of these, patients may also exhibit other stereotypic behaviors, including position shifting, touching objects, repetitive movements of the mouth or jaw or fingers, and verbalizations (4).

DIFFERENTIATING STEREOTYPIES FROM OTHER REPETITIVE MOVEMENTS (Table 22.4)

Differentiating a stereotypy from other movement disorders can be difficult as the patient, especially if younger, is often unable to describe what they are feeling or doing. Listed below and in Table 22.5 are several differential diagnoses to consider when evaluating repetitive movements.

MANNERISMS

Mannerisms are also described in a variety of ways but typically involve peculiar or idiosyncratic gestures or embellished movements, in otherwise normal individuals, that are part of some other goal-directed behavior. Such movements include those that a baseball player may exhibit while awaiting a pitch, such as touching the helmet brim, tapping the bat on the ground, or drawing a figure in the dirt, or those that a basketball player might do prior to a free throw, such as touching the face, dribbling a set number of times, or spinning the ball in a specific manner. These are generally accepted as “normal variants,” are typically unique to the individual, are under conscious control, and are often less complex and briefer than stereotypies.

HABITS

Habits are “repetitive, coordinated movements that are commonly seen in otherwise normal individuals, particularly during times of anxiety, self-consciousness, boredom, or fatigue” (4). They can include a wide variety or movements, including eye rubbing, ear pulling, nail-biting/picking, finger sucking, hair twirling, cracking finger joints, manipulation of clothing or jewelry, and foot tapping. These same actions may be considered compulsion or tics depending upon the setting in which they occur and the sensory or mental drive behind them.

| Differential Diagnosis of Stereotypic Movements |

Mannerism/motor habit

Motor tics

Tardive dyskinesia

Restless leg syndrome

Ictal automatisms

Self-stimulation

Repetitive behaviors secondary to other psychiatric conditions

Repetitive behaviors secondary to other medical conditions (i.e., cerebellar disorders, third ventricular masses, nystagmus, spasmus nutans)

Akathisia

COMPULSIONS

Compulsions or compulsive behaviors are persistent, repetitive behaviors, under conscious control, that are often performed to reduce internal feelings or obsessions that a person wishes to control. They are most often seen as part of OCD or obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders (OCSD), which are due to “cognitive intrusions” and “sensory intrusions,” respectively (21). They can include ritualistic behavior and repetitious behaviors such as checking door locks and hand washing.

MOTOR TICS

Motor tics are sudden, repetitive, brief, stereotyped movements that can be divided into simple and complex subtypes. Simple tics are brief movements, such as eye blinking, head turning, or grimacing that occur alone or in trains. Complex tics are more elaborate sequences of movements such as trains of grouped actions, head nodding, or abnormal postures. They may or may not be associated with vocalizations. They often occur in the setting of Tourette’s syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree