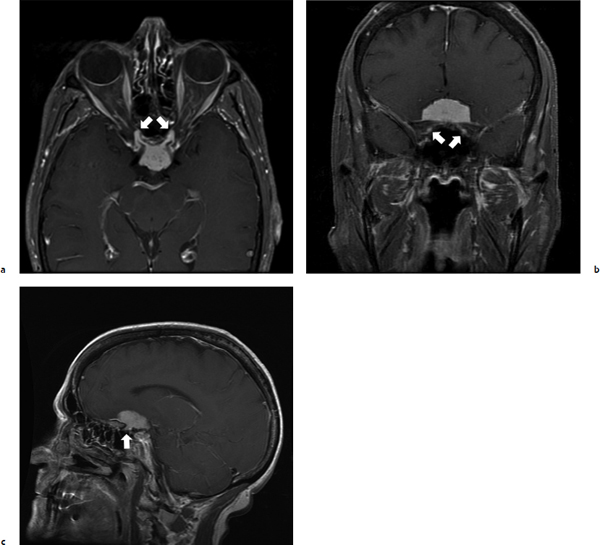

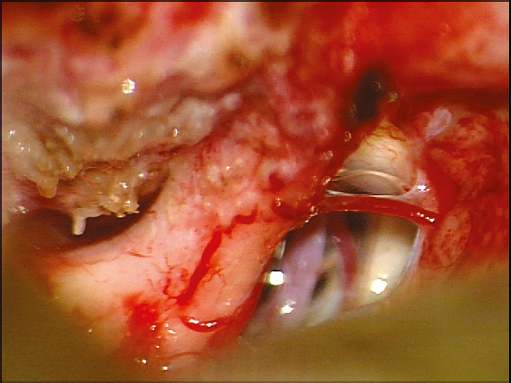

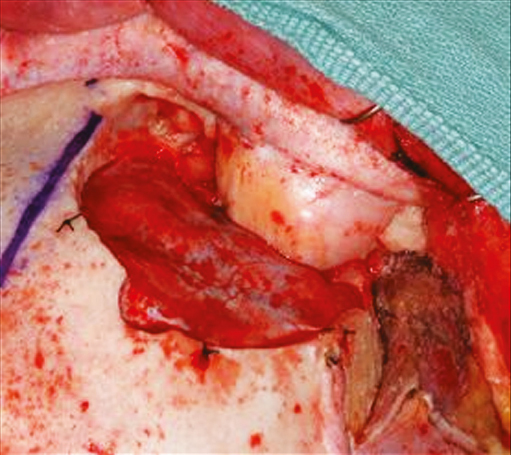

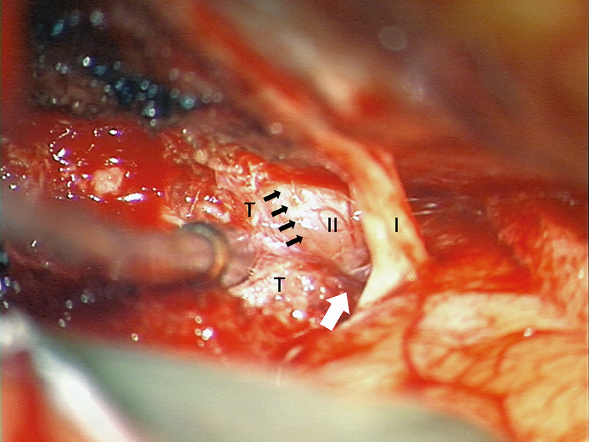

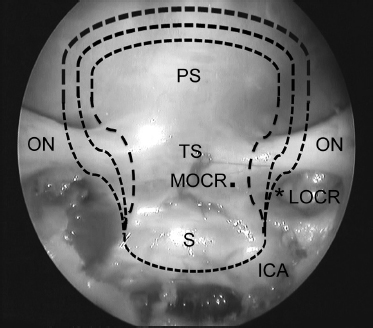

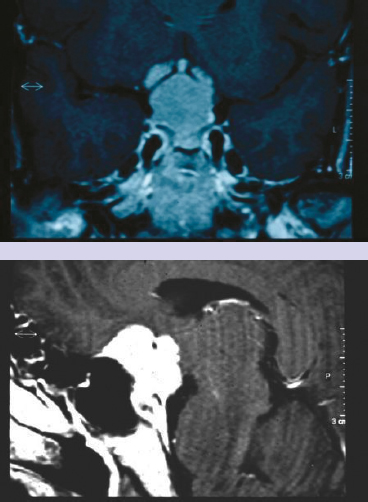

Chapter 1 Case A 45-year-old woman has visual acuity of 20/800 in the right eye, 20/40 in the left eye, and an incongruous visual field defect. Participants Microsurgical Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: Franco DeMonte Endoscopic Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: Paolo Cappabianca, Luigi Maria Cavallo, Felice Esposito, and Domenico Solari Moderator: Surgical Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: Endoscopic vs. Microscopic: William T. Couldwell Meningiomas of the tuberculum sella account for 4 to 10% of meningiomas, and they almost universally present with varying degrees of visual loss.1 These tumors arise from the tuberculum sellae, chiasmatic sulcus, limbus sphenoidale, and the diaphragma sellae, and usually displace the optic chiasm superiorly and posteriorly and the optic nerves laterally or anterolaterally and superiorly. They very commonly extend into one or both optic canals.2–4 Early diagnosis and advances in microsurgical technique have essentially eliminated mortality in recent microsurgical series, but even contemporary studies continue to report up to a 20% rate of visual deterioration after surgery.5–10 There recently has been a proliferation of reports describing the transsphenoidal resection of tuberculum sellae meningiomas, with both microsurgical and endoscopic techniques, although the patients included in these reports represent a highly selected subset of these tumors. Crucial to the patient’s visual outcome and the selection of the operative approach is the surgeon’s ability to recognize the high rate of optic canal extensions of tuberculum sellae meningiomas (Fig. 1.1). Such extensions have been identified in 75% of patients or more,2,4 and early optic canal decompression is an important factor in optimizing visual outcome.2,3,9,11 Similarly crucial to visual outcome is the preservation of the small vessels to the inferior surface of the optic nerves and chiasm. These vessels are part of the superior hypophyseal arterial complex that arises from the medial wall of the internal carotid artery bilaterally12,13 (Fig. 1.2). Fig. 1.1a–c Axial (a), coronal (b), and sagittal (c) T1-weighted postcontrast magnetic resonance imaging studies of a patient with a large tuberculum sella meningioma with bilateral extension into the optic canal (arrows). (Used with permission of the Department of Neurosurgery, the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.) Vascular encasement, especially of the anterior cerebral arteries (ACAs) and the anterior communicating artery, must be addressed through careful, precise arachnoidal microdissection to prevent perforator injury.1,12 Occasionally, contributions to the tumor’s blood supply may come from small branches of the anterior cerebral and anterior communicating complex. This supply needs to be interrupted but the parent vasculature preserved. The pituitary stalk is typically displaced posteriorly and is usually not difficult to dissect from the tumor. Liliequist’s membrane tends to remain intact; thus, separating the posterior portion of the tumor is usually relatively straightforward even in the presence of marked posterior displacement of the basilar artery.14 This patient is a 45-year-old woman with significantly compromised vision and vascular encasement of the ACA and anterior communicating artery complex by a relatively large tuberculum sellae meningioma (see images at the beginning of the chapter). She is best served by the complete microsurgical resection of the tumor. The approach selected must accomplish several goals: 1. Allow for the circumferential decompression of, and tumoral dissection from, the optic nerves. 2. Preserve the microvasculature of the optic nerves and chiasm. 3. Allow precise arachnoidal microdissection to free the encased ACA and anterior communicating artery complex. 4. Allow access to, and removal of, the tumor, the dura of origin, and any hyperostotic bone. 5. Preserve the pituitary stalk and endocrinologic function. 6. Allow for reliable dural repair and reconstruction to avoid leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Given the degree of visual compromise and the vascular encasement, I would choose a right-sided fronto-orbital approach (Fig. 1.3). In this approach, microdissection is used to separate the right olfactory tract from the inferior surface of the frontal lobe back to the olfactory trigone. The anterior falcine insertion is identified and used for midline orientation. Tumor devascularization begins in the midline, and careful tumor debulking is begun. The ipsilateral optic nerve is identified. Before manipulating the optic nerve, the surgeon removes the dura overlying the optic canal (typically involved with tumor), and the bony optic canal is widely opened with a high-speed drill and diamond bur or ultrasonic bone curette and constant irrigation. The falciform ligament and the dura of the optic canal are opened to decompress the optic nerve. Tumor is removed from around the ipsilateral optic nerve, and the right internal carotid artery is identified. Care must be taken to avoid injuring the ophthalmic artery. Precise arachnoidal microdissection is used to remove tumor from around the ACA and anterior communicating artery complex. The right optic nerve is followed to the chiasm, and the left optic nerve is subsequently identified. This nerve is then decompressed through opening of the bony and dural optic canal, and tumor is removed from around the left optic nerve. The final dural attachments are divided and the posterior margin of the tumor is dissected off the pituitary stalk and Liliequist’s membrane. All of the involved dura is resected and any hyperostotic bone is drilled away. Fig. 1.3 Intraoperative photograph of the right supraorbital craniotomy used to approach tuberculum sella meningiomas. (Used with permission of the Department of Neurosurgery, the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.) Dural reconstruction is done with an intradural graft sewed to the dura of the base where possible. Vascularized pericranium is readily available to augment the reconstruction and to separate the sinonasal cavity from the intracranial space. The optimal treatment for a patient with a meningioma of the tuberculum sella is the complete removal of the tumor, normalization of the patient’s vision, and freedom from surgical complications. Over the past decade, these outcomes have most commonly been achieved by using a transcranial route to access the tumor.1–5,8–19 More recently, anterior-based approaches through the sinonasal cavities have been proposed and increasingly used to achieve these same goals through what is perceived to be a less morbid alternative to craniotomy.20–31 The transcranial, microsurgical resection of a tuber-culum sellae meningioma, be it through subfrontal, interhemispheric, or pterional routes, has many advantages. It allows vascular control of the internal carotid artery, ACA, and middle cerebral artery; direct decompression and inspection of the optic canals, nerves, and chiasm; multiple local tissues (free and vascularized) for reconstruction; and a great degree of familiarity among neurosurgeons. Using these various transcranial routes, surgeons have reported gross total resection rates of 73 to 98%, with a mean rate of 90.5% (median 85%). The tumors described in these reports ranged from 0.5 to 8 cm but averaged 2.8 cm (median 2.7 cm).2–13,15–19 In contradistinction, a mean gross total resection rate of 76% has been reported when a transsphenoidal route is used, be it traditional or endoscopic (range 57 to 85%, median 83%), with tumors ranging from 1.2 to 3.7 cm (mean 2.2 cm, median 2.3 cm).20,23,24,27,28,30 Thus, it seems that a less complete extent of resection is achieved with transnasally based approaches despite a population of patients with smaller tumors on average (selected patients). Of primary concern when treating a patient with a tuberculum sellae meningioma is the patient’s visual outcome. Often the optic nerves and chiasm are markedly compressed, distorted, and thinned. Many surgeons believe that the optic canals should be opened and the optic nerve decompressed before direct dissection of the nerves and chiasm takes place. Mathiesen and Kihlström9 were able to achieve a 91% rate of visual improvement in their patients when proceeding in this manner. This figure can be compared with an overall mean rate of visual improvement of 59% reported in the microsurgical literature.2–11,13,15–19 Unfortunately, this same body of literature reveals that visual worsening remains a significant problem, with a mean rate of visual decline of 13%.2–11,13,15–19 Fig. 1.4 Intraoperative photograph during a right supraorbital approach to a tuberculum sella meningioma. The olfactory (I) and optic (II) nerves are labeled, as is the tumor (T). Note the nearly indiscernible plane between the tumor and the medial edge of the optic nerve (small black arrows). Also note the tumor extending superolateral to the optic nerve (white arrow). (Used with permission of the Department of Neurosurgery, the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center.) In the most typical arrangement, the optic nerves are elevated superiorly and laterally and the chiasm superiorly and posteriorly by the tumor. This pathological anatomy most favors an inferomedial approach for decompression as the approach least likely to require manipulation of the optic nerve or chiasm.21,23,29 This is likely the reason for the improved visual outcome reported in the literature for anteriorly based surgical approaches. Rates of visual improvement ranging from 71 to 100% have been reported (mean 85%), whereas visual deterioration has been reported in less than 5%.20,23,24,27,28,30 A drawback of this approach, however, is the inability to remove tumor extensions above or lateral to the optic nerves (Fig. 1.4). Another unfortunate by-product of this inferomedial exposure of the optic nerves and chiasm is the direct communication of the intradural space with the sinonasal cavity and the paucity of reconstructive options available to achieve a watertight closure, let alone a primary closure. Mean rates of CSF leaks of 30% have been reported, although meningitis does not seem to be common.20,23,24,27,28,30 The transcranial microsurgical literature reports mean CSF leak rates of 4%.2–11,13,15–19 Finally, there is also a greater chance of trauma to the pituitary gland and stalk with the transnasally based approaches. The literature reports an almost twofold increase in the incidence of diabetes insipidus (6.4% vs. 3.5%) after surgery.2–11,13,15–20,23–25,27,28,30 Although great strides have been made in the use of transnasal techniques to access the anterior cranial base and sellar region, many questions remain about the indications for their use in the treatment of a patient with a tuberculum sellae meningioma. According to findings reported in the literature to date, the transcranial routes have the advantages of applicability to tumors of any size, a better extent of resection, lower rates of endocrinopathy and spinal fluid leakage, and, with early decompression of the optic nerves, impressive rates of visual improvement. Currently, these approaches most closely meet the ideals of complete tumor removal, normalization of vision, and freedom from surgical complications in patients with a tuberculum sellae meningioma. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas account for 5 to 10% of all intracranial meningiomas. Such tumors often compress and sometimes encase neighboring neurovascular structures, namely the optic nerves and chiasm, the pituitary stalk, the hypothalamus, the third cranial nerve, and the internal carotid, anterior cerebral, and anterior communicating arteries. Hence, they have been historically managed through different and extensive transcranial approaches. During recent decades, however, with the contributions of microsurgery and especially the “keyhole surgery” concept, surgical techniques and the results of treatment have been significantly refined, with a tremendous improvement in terms of morbidity and mortality rates. More recently, the evolution of endoscopic techniques has progressively reduced the invasiveness of transcranial approaches and stimulated new interest in transsphenoidal surgery. Indeed, the panoramic view offered by the endoscope has improved the safety of the transsphenoidal approach,32–35 creating the possibility of passing through the nasal cavity to reach the brain and its neurovascular structures without parenchymal manipulation or retraction. Thus far, use of the endoscope has extended indications for such an approach, initially reserved for sellar or intra-suprasellar intradiaphragmatic lesions,33,34,36,37 to different “pure” supradiaphragmatic lesions, including tuberculum sellae meningiomas.20,23,24,27,29–31,38–41 This application had already been foreseen by Hardy42 in the 1970s. The visualizing tool for this kind of approach is the same as that used during standard transsphenoidal surgery: a rigid 0-degree endoscope 18 cm in length and 4 mm in diameter (Karl Storz Endoscopy, Tuttlingen, Germany). Notwithstanding the close proximity of the sellar, suprasellar, and tuber-culum-planum sphenoidal areas, the endoscopic endonasal approach requires some modifications from the standard approach traditionally adopted to access the sella. The endoscopic endonasal approach for the treatment of tuberculum sellae meningiomas should give surgeons the opportunity to proceed through the same surgical steps as those provided by the adoption of a classic bimanual microsurgical technique—devascularization, debulking, and dissection—that represent the backbone of meningioma surgery. Because the surgical corridor routinely used in the standard approach to the sellar area is not sufficient, a wider, bi-nostril surgical corridor, attained by removing some nasal structures, must be established to increase the working space and the maneuverability of instruments, according to the basic rules for the extended endoscopic approaches to the skull base standardized by Kassam and associates.43–45 Hence, the middle turbinate on one side (usually the right) and the posterior portion of the nasal septum are removed, and the middle turbinate in the other nostril is lateralized (sometimes even this turbinate can be removed). If needed, the superior turbinate and the posterior ethmoid air cells on both sides can be removed to increase the working space. Thereafter, a wider anterior sphenoidotomy is performed; all the septa inside the sphenoid sinus are removed, and every irregularity of the bone and mucosa is flattened to increase the maneuverability of the endoscope and surgical instruments while working above the sella. Once the posterior wall of the sphenoid sinus is completely exposed, a series of protuberances and depressions (according to the grade of pneumatization) becomes visible: the sellar floor at the center, the sphenoethmoid planum above it, and the clival indentation below; the bony prominences of the intracavernous carotid artery and the optic nerves laterally; and between them the opticocarotid recess molded by the pneumatization of the optic strut of the anterior clinoid process. In such a way, it is possible to create a corridor that allows the surgeon to perform bimanual dissection through both nostrils while a coworker holds the endoscope, dynamically moving it along the surgical corridor and switching between the close-up and panoramic views of the surgical field on demand. Once such a preliminary stage has been performed, additional bone is removed from the cranial base: the tuberculum sellae and the planum sphenoidale anteriorly, depending on the extension of the meningioma, up to the level of the posterior ethmoidal arteries and laterally up to both medial opticocarotid recesses. This aspect of such a bony depression, limited by the parasellar portion of both the intracavernous carotid arteries and the optic nerves, corresponds intracranially to the entrance of the optic canals.43 Bone removal at this level can be extended more laterally up to the medial border of the lateral opticocarotid recess, which corresponds intracranially to the optic strut of the anterior clinoid process, to expose the optic canals. Superiorly, the bone opening can be widened over the planum because the optic nerve diverges, so that the resulting craniectomy resembles a chef’s hat46,47 (Figs. 1.5, 1.6). The neuronavigator has proved to be quite useful in better defining the limits of bone removal. Unlike with craniopharyngiomas, in the endoscopic endonasal approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas, management of the superior intercavernous sinus is not so troublesome because the tumor itself often compresses and obliterates the sinus. At this point in the procedure, management of the lesion can begin. The fundamental steps of dissection and removal are tailored to each lesion, according to the standard principles of transcranial microsurgery. When approached from below, removal of a tuberculum sellae meningioma is preceded by coagulation of the dural attachment so that the tumor is devascularized early. Thereafter, the tumor is debulked safely and its capsule is finally dissected from the surrounding microvascular structures either with or without manipulation of the optic pathways. Fig. 1.5 Anatomic endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal view showing the “chef’s hat”–shaped bone and dural opening (dashed lines) to gain access to the suprasellar area. Such an opening can be tailored according to the lateral extension of the lesion. In the inferior portion, bone can be removed up to the medial border of the lateral opticocarotid recess, which corresponds intracranially to the optic strut of the anterior clinoid process so that even the optic canals can be exposed in their inferomedial aspects. The opening can be widened over the planum. ICA, internal carotid artery covered by the dura mater; LOCR, lateral opticocarotid recess; MOCR, medial opticocarotid recess; ON, optic nerve covered by the dura mater; PS, planum sphenoidale; S, sella; TS, tuberculum sellae; *, medial aspect of the lateral opticocarotid recess.

Surgical Removal of

Tuberculum Sellae Meningioma:

Endoscopic vs. Microscopic

Microsurgical Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas

Surgical Considerations

Treatment of the Controversial Patient

Discussion

Conclusion

Endoscopic Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas

From the Sellae to the Tuberculum

Lesion Management

Surgical Removal of Tuberculum Sellae Meningiomas: Endoscopic vs. Microscopic

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree