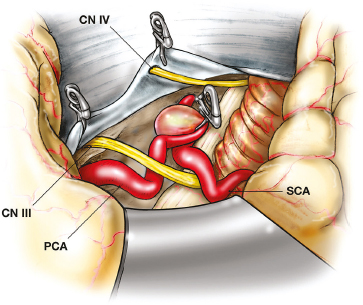

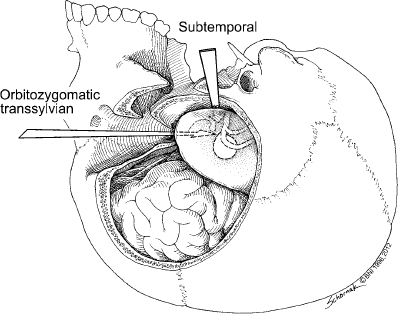

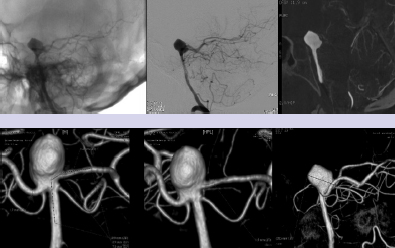

Chapter 15 Case A 40-year-old woman who smokes cigarettes and has hypertension presents with subarachnoid hemorrhage of Hunt and Hess grade I and Fisher grade I. The imaging studies include digital subtraction angiography and three-dimensional reconstruction. Participants Treatment of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms: Endovascular Treatment with Stent and Coil: Bernard R. Bendok, Salah G. Aoun, and Tarek Y. el Ahmadieh Microsurgical Clipping of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms: Juha Hernesniemi and Miikka Korja Moderators: Treatment of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Apex Aneurysms: Shakeel A. Chowdhry and Peter Nakaji Basilar apex aneurysms pose unique challenges and technical issues from both the endovascular and surgical perspectives. Microsurgically these lesions can be difficult to treat, but not all basilar apex aneurysms pose the same degree of microsurgical difficulty. From an endovascular perspective, the dome-to-neck ratio, the absolute dome and neck sizes, and the relationship of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) to the neck can all affect the acute and delayed risks and outcomes. The location of basilar tip aneurysms puts these lesions at a hemodynamic disadvantage vis-à-vis a recurrence risk because of the impact of blood flow on the behavior of the aneurysmal fundus and blood pulsations on the stability of the coil complex. Many factors can alter the therapeutic recommendations and risk–benefit analysis, including the aneurysm’s neck and dome dimensions, the dome’s projection, the PCA anatomy, the relationship of the neck to the posterior clinoid process, and the patient’s age and comorbidities. In this interesting and challenging case, the dome of the aneurysm appears to be approximately 15 mm and the neck is likely greater than 6 mm depending on how it is measured. The PCAs are offset, with the left PCA being slightly higher in the craniocaudal dimension. The neck is approximately at the level of the posterior clinoid process, and the tilt of the dome is straight up. From a surgical perspective, the key determinant of risk is the anatomy of the perforators and the ability of the surgeon to preserve their patency without injury. From an endovascular perspective, the key determinant of risk in this case is the wide neck, which increases the likelihood of compromising the left PCA, coil herniation, incomplete aneurysm occlusion, and thromboembolic complications. The risk of recanalization is significant in this aneurysm given its size, and a stent may help attenuate this risk. Although early aneurysm repair has become the norm for most ruptured intracranial aneurysms, delayed treatment can be considered in select patients with highly complex lesions. An attempt should be made to treat this aneurysm, but difficulties encountered along the way may favor a delay in therapy. From an endovascular perspective, there are six therapeutic options we would consider for this aneurysm and patient: 1. Coiling without an assist device 2. Balloon-assisted coiling with an attempt at complete occlusion 3. Stent-assisted coiling 4. Flow diversion 5. Coiling after partial clipping 6. Partial balloon-assisted coiling followed by delayed stent coiling Advances in microsurgical techniques, neuroanesthesia, and cranial-base approaches have improved microsurgical outcomes over the past two decades. An extended lateral transsylvian approach from the right would be our choice for this aneurysm. A zygomatic osteotomy with drilling of the posterior clinoid process may add additional welcome millimeters to the exposure. An extended subtemporal approach could be an alternative. Clipping has the advantage of being associated with a minimal risk of recurrence if complete or near-complete occlusion is achieved. Additional benefits include less exposure to radiation when compared with endovascular approaches and less need for follow-up imaging. For a good outcome to be achieved, however, the precious perforators that emanate from the proximal P1s and occasionally the neck behind the aneurysm must be preserved. This simply cannot be compromised. If the aneurysm cannot be completely occluded during surgery, the neck can be narrowed with a clip followed immediately by aneurysm coiling. Hybrid surgical suites may allow for more efficient execution of this strategy. The main advantage of the endovascular approach is the decreased risk of perforator injury. The endovascular options for this aneurysm are listed above, and their success depends on a thoughtful analysis of these options and execution of the chosen option with the least risk possible. Unlike for open surgery, a philosophy of staging should be considered if the total risk is acceptably low and, ideally, lower than a single-stage approach. Although coiling this aneurysm without an assist device may be potentially feasible with modern three-dimensional coils, we would be concerned about the significant risk of herniation of the coil loops into the parent vessels with the potential for thromboembolic complications. This approach would not be our first choice for this patient, although an attempt to see how the first coil behaves is not unreasonable. We would recommend having a balloon ready in the parent arteries. Balloon-assisted coiling allows for the potentially increased protection of the parent arteries during the coiling procedure and provides support for the coil complex until it is sufficiently stable to remain inside the aneurysm with a minimal risk of protrusion into the parent arteries. It also has the advantage of not requiring antiplatelet therapy after the coiling procedure, and has thus gained popularity for the treatment of ruptured wide-necked aneurysms. Additional potential benefits of using a balloon include a greater packing density and the prompt ability to address intraprocedural rupture. These would be welcome advantages in this challenging case. However, the rate of thrombus formation and thromboembolic complications may be high during balloon-assisted coiling procedures, especially with wide-necked compared with narrow-necked aneurysms. Certainly, if the coiling is going well, complete occlusion can be aimed for, but this could have the disadvantage of increasing thromboembolic risks from prolonged procedure time and the lack of preprocedural antiplatelet agents, which are generally avoided in the acute period of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stent-assisted coiling would certainly simplify the coiling of this aneurysm from a technical standpoint, and we would guess that it could be done with one stent from the left PCA to the basilar artery (Fig. 15.1). Y-stenting and waffle cone techniques would not be our first choice because of the added but likely unnecessary complexity. Our concern regarding this strategy stems from the now well-established body of literature that has shown increased morbidity and mortality with this approach because of the need for dual antiplatelet agents in the acute period of subarachnoid hemorrhage. External ventricular drain-related hemorrhages appear more likely and more morbid when dual antiplatelet agents are on board. The use of dual anti-platelet agents also complicates other potential procedures, such as tracheostomies and the placement of gastrostomy tubes. Certainly, there are scenarios in which there are no other good options and this increased risk becomes acceptable. On the surface, that does not appear to be the case here. The use of flow diverters in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage has not yet been well evaluated. Risks include those related to the acute administration of antiplatelet therapy in an acute subarachnoid hemorrhage setting and those linked to the fact that the aneurysmal fundus is left unobliterated and may not thrombose with the concurrent platelet deactivation. The inability to easily reaccess the dome adds a layer of concern that is problematic. Additional concerns include the potential for thromboembolic complications and parent-artery occlusion up to 2 years after placement of a stent. This has been noted days to weeks after the discontinuation of antiplatelet treatment. Considering the specific circumstances of this case, this may not be an optimal approach to treat the patient’s aneurysm. Moreover, at the time of this writing, this patient’s aneurysm would not meet the strict guidelines of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regarding the use of the currently available flow diverter. In our practice and hands, this strategy would be low on the list of options for this patient. On rare occasions, the findings at surgery can limit the surgeon’s ability to close the neck of an aneurysm completely. The perforator anatomy and neck calcifications are the main determinants of this potential scenario. The good news is that even a partial reduction in the neck size in this case could potentially simplify the endovascular approach. Ideally, partial clipping should protect the higher P1. Coiling should be done immediately to prevent rehemorrhage. A hybrid operating room with immediate access to biplane angiography before the craniotomy is even closed would be ideal for this rare but potentially safe and effective scenario. Clearly, this approach is not without its own set of risks. The use of intravascular catheters without full anticoagulation may predispose to thromboembolic complications. Partial balloon-assisted coiling followed by delayed stent coiling may be an excellent strategy here and the one we would favor. The key issue is determining what degree of partial coiling is enough to prevent rerupture in the ensuing several weeks until more definitive therapy is instituted. In our opinion, if the upper two thirds of the dome are well packed, with loose coiling in the lower third, the patient should be protected in the short term (Fig. 15.2) unless the rupture site is near the neck (which is very rare and is usually seen in the form of a suspicious daughter sac at the neck). This approach has the advantage of minimizing thromboembolic complications and limiting the procedure time. Placing only a few coils in the dome with significant residual interstitial filling, on the other hand, is not likely to be sufficient to prevent rehemorrhage. The use of antiplatelet agents becomes much safer after the acute period of subarachnoid hemorrhage (arbitrarily defined as 2 to 3 weeks after the initial hemorrhage). The end of the acute period implies that hydrocephalus, gastrostomy tube, and tracheostomy issues are dealt with to minimize the risk from dural antiplatelet therapy, which is needed for stenting. Stenting has the potential advantages of narrowing the neck, protecting the parent arteries, and increasing the packing density (Fig. 15.3). Our group has demonstrated an increased packing density, increased coil loop density at the neck, and better angiographic outcomes in an in-vitro model. Some studies suggest lower recanalization rates when stents are used. Whether the risk is increased by adding a stent remains controversial, and we would argue that the risk may actually be reduced by using a stent in this case. Given the clinical presentation of the patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage and her young age, surgical clipping of the aneurysm as a means of providing a definitive cure might be considered as a first-line treatment, with potential perforator injury being the most significant potential risk. Endovascular treatment can be a safe and effective alternative, with thromboembolic complications and recurrence being the two most significant risks. The large size of this aneurysm and the wide neck with potential risk to the left P1 would not make this aneurysm an “equipoise case” in randomized trials of clip versus coil. In fact, viewing this case through the prism of “clip versus coil” may hinder the appreciation of creative solutions, which may be hybrid, staged, or both. The treating team must appreciate that managing this aneurysm carries significant risks, and that this risk should be put in compassionate perspective for the patient and her family. The question is which strategy offers the lowest possible risk profile with the greatest chance for both short-term and long-term success. In our opinion, complex aneurysms such as this should ideally be managed at centers with high levels of expertise in cerebrovascular cranial-base microsurgery as well as neurointerventional surgery. From an interventional perspective, the option we favor for this aneurysm is initial coiling with balloon assistance if feasible. Coiling at least two thirds of the dome should be the initial goal, with further coiling and stent assistance after the acute subarachnoid hemorrhage period has passed. If the initial endovascular approach proves difficult and the risk seems to outweigh the benefit, then a microsurgical approach should be embraced. Fig. 15.2 Balloon remodeling with dense packing of the upper two thirds of the aneurysm and lower density packing of the lower third. The authors express gratitude to Miss Nour Aoun for her excellent illustrations. If only we could have back again many of those who were lost or badly hurt, for a second chance in the operative room with what we have learned. —C.G. Drake, S.J. Peerless, and J.A. Hernesniemi, 1996 This aneurysm is a medium- to large-sized (around 15 mm in diameter) basilar bifurcation aneurysm projecting upward. The patient is young with a long life expectancy, and we would try to persuade her to stop smoking. To have the most permanent long-term result, we would suggest open microsurgery as the best option for perfect occlusion of this deadly sac. For more than 10 years, computed tomography (CT) angiography has served us as the most satisfactory diagnostic workup for cerebral aneurysms, because it shows clearly the anatomic relationship between the aneurysm and the skull base. As far as we can assess the digital subtraction angiography images of the case, the base of the aneurysm appears to be at the level of the posterior clinoid process (see the figures presented with the case), but a good three-dimensional CT angiography image would give more information. The best projection for open microsurgery would be the forward projection of the sac, but this is the rarest type. Because the base of the aneurysm is at the level of the posterior clinoid process and there are no other anterior circulation aneurysms, our approach is subtemporal (Fig. 15.4). The transsylvian route is mostly used in patients with basilar tip aneurysms with a high location, especially when the aneurysm is approximately 1 cm or more above the posterior clinoid process. The patient is placed in the park-bench position, and the brain is slackened by an experienced neuroanesthesiologist, with simultaneous lumbar drainage of 50 to 100 mL of cerebrospinal fluid. The lumbar drain is always introduced by the operating neurosurgeon, as it gives a feeling of safety, comfort, and success for the surgery. Fig. 15.4 The subtemporal approach requires slight retraction of the temporal lobe. The oculomotor nerve, which always lies between the P1 segment and the superior cerebellar artery (SCA), serves as a highway to the basilar bifurcation. The tentorial flap can be fixed with, for example, small Aesculap clips. CN, cranial nerve; PCA, posterior cerebral artery. Since the first successful subtemporal approach to a basilar bifurcation aneurysm by Olivecrona in Sweden in 1954, two basic surgical approaches have been widely used to attack basilar tip aneurysms: the subtemporal (since 1959 and mastered by Drake) and the transsylvian (frontotemporal or pterional described by Yasargil in 1976). Subsequently, numerous innovative microsurgical approaches have been tested for their value in the treatment. Both of these approaches are complex, and they destroy, more or less, some parts of the cranial base. Some surgeons prefer the transsylvian approach because of its familiarity (it is used for anterior aneurysms) and because it possibly entails less retraction of the temporal lobe and causes fewer third nerve palsies. In our series and the series from London, Ontario, however, the subtemporal approach has been used in more than four fifths of patients with small and large basilar tip aneurysms. Patients with additional anterior circulation aneurysms in the middle cerebral or anterior communicating arteries should undergo the pterional approach, but internal carotid aneurysms can often be ligated through the subtemporal route rather easily. There is no doubt that many aneurysms arising from the basilar tip can be approached through most of the described, and often complex, operative techniques. The surgeon’s preference or experience determines the choice of the safest technique. For a notable number of patients, however, only one approach can lead to accurate and safe clipping of the aneurysm. A scrutiny of the 895 basilar bifurcation aneurysms operated on mainly at the teaching hospitals of the University of Western Ontario in London, Canada, between 1959 and 1992 showed that 137 were giant (25 mm or more) and were omitted from the analysis for obvious reasons. Incomplete radiological data or endovascular surgery excluded 63 more cases. Of those remaining, 440 patients with small (< 12 mm ie. ½ inch) and 255 patients with large (12–25 mm ie. ½ inch) basilar bifurcation aneurysms were analyzed. Of these, 95 patients underwent the transsylvian approach and 600 the subtemporal approach. The position of the basilar bifurcation and aneurysmal neck was assessed as follows: 1. Above the posterior clinoid process (more than 3 mm above the level of the posterior clinoid process) 2. At the posterior clinoid process (more than 3 mm above or below the level of the posterior clinoid process) 3. Below the posterior clinoid process (more than 3 mm below the level of the posterior clinoid process). Most often, the right-sided subtemporal approach is used. If the projection or complexity of the aneurysm favors the left-sided approach, or a patient has a left oculomotor palsy, left-sided blindness or right hemiparesis, the approach under the dominant temporal lobe is preferred. Additional aneurysms in the anterior circulation have an important impact on the choice of operative side, and more than one fourth of patients eventually have a left-sided craniotomy. However, left-sided carotid aneurysms are often left for a second operation or conservative management. In our experience, the left-sided transsylvian route is slightly more uncomfortable than the right transsylvian approach for the right-handed surgeon. Nowhere are the perforators more numerous or critical than at the basilar artery bifurcation. Most perforators can be dissected free with a tiny dissector after temporary occlusion or trapping of the basilar artery. The perforators in backward-projecting aneurysms can often be separated more easily than expected from the neck when the sub-temporal approach is used. In these cases, a forward sac-tilting maneuver opens a clear space between the neck and the perforating branches. In spite of the complex perforator anatomy, most of these patients fare well. The transsylvian approach does not allow the same visualization behind the aneurysm, and the results of this approach were the poorest of all in the London, Ontario, series. The outcome of surgery is best in patients with an aneurysm located above the posterior clinoid process, whatever the projection of the aneurysm and for both approaches. In the London, Ontario, series, the best results were seen in patients with forward-projecting aneurysms above the posterior clinoid process, and the worst for the same projection but below the posterior clinoid process. The worst combination of anatomic features was a very low location and forward projection. These aneurysms warrant the greatest respect among all basilar bifurcation aneurysms; the number of intraoperative aneurysm ruptures and inadvertent major vessel occlusions was highest in this subgroup. The transsylvian approach is inappropriate for most of these low-lying lesions, for it is difficult, if not impossible, to see the lesion without removing the dorsum sellae. The higher rate of low-lying lesions (32%) in the series of Drake and Peerless may be the result of a referral bias. In these series, the posterior clinoid process was never removed but instead avoided by selecting the proper approach. The complex anatomy of bilobular aneurysms is often best exposed from the lateral side, and the good results achieved in these rare aneurysms stem from the use of the subtemporal approach and two aneurysm clips, one for each lobe (necessary in four of 14 aneurysms in the series). The higher the aneurysm lies above the dorsum sellae, the greater the retraction of the mesial temporal parahippocampal region must be during the subtemporal approach. If the neck of the sac reaches the apex of the interpeduncular space, the neck and perforators are more likely hidden by the mammillary bodies and peduncle. These rare cases with a very high bifurcation (< 1%) are preferentially approached after the sylvian fissure is split, and the surgeon eventually works above the carotid bifurcation or uses the lamina terminalis or interforniceal approach. The neck of an aneurysm is completely obliterated when the clip blades fall across the neck parallel to the posterior cerebral arteries, and then there is less risk of kinking the bifurcation; this is true particularly for aneurysms with large necks. This ideal placement is more readily achieved through the subtemporal approach. Clips placed perpendicular to this crotch often leave tags of the neck in front and behind (“dog ears”), as the sides of the neck are approximated and the bifurcation crimped. “Dog ears” of the residual neck may grow into new aneurysms. Many recent series report that the transsylvian approach results in fewer third nerve palsies. In general, resolution of the third cranial nerve palsy is excellent even when complete paralysis exists postoperatively. After a few weeks or months, recovery is complete in practically all patients in whom no paresis exists preoperatively. When the basilar bifurcation aneurysm has been clipped through the pterional approach between the optic nerve and carotid artery, the likelihood of a postoperative oculomotor palsy is almost nonexistent. The use of very high magnification in operating on these aneurysms has markedly reduced the incidence of immediate oculomotor palsies. In patients with unilateral carotid stenosis or occlusion, the subtemporal approach should be preferred. As in the transsylvian approach, carotid compression can cause complications and a carotid injury is a well-known complication. Admittedly, it is easier in acute and early aneurysm surgery to obtain space through a small subfrontal gap to open the lamina terminalis than to obtain room in the sub-temporal approach. This can be facilitated by a ventricular tap and spinal drainage. Proximal control is easier in the subtemporal route than in the pterional one. A “half-and-half” combination of the two approaches is useful when the transsylvian exposure does not allow visualization of the back of the neck of larger aneurysms, or when the neck has a more horizontal takeoff posteriorly. A mobile temporal pole may be readily displaced backward, but it is not wise to divide large temporal-sphenoidal veins, for severe temporal edema or hemorrhage may occur. Without these veins, the half-and-half approach is the ideal one, for it combines the good features while minimizing the drawbacks of both. If tethered by the veins, the pole may be elevated to allow dissection on either side of the third nerve behind the neck to clear the perforators. Then the clip may be applied from various angles with all vessels in view. By deeply respecting the work and achievements of two great neurosurgeons, C.G. Drake and S.J. Peerless (personal communication), we finish this comment by citing their lifetime, never-to-be-repeated experience: Nearly all (99%) of nongiant basilar bifurcation aneurysms can be visualized subtemporally regardless of their size, height, direction or multilocularity. The inner third of the tent can be divided smoothly for very low necks and placement of a temporary basilar artery clip. There is no necessity to remove the posterior clinoid process or inner petrous apex. In fact, we do not understand the benefits of an extensive removal of an obstacle when you can evade it. Exactly, one of the great advantages of [the] subtemporal approach is its simplicity without extensive removal of [the] base of [the] skull. Replacement of the small bone flap gives excellent cosmetic results. Finally, control of forceful hemorrhage from inadvertent rupture of the aneurysm is far easier through the subtemporal rather than a transsylvian exposure. These advantages have outweighed the minor risks associated with temporal lobe retraction and the reported, more frequent, temporary third nerve paresis. The transsylvian exposure is suitable in 56% of basilar bifurcation aneurysms in our case series. It is most appropriate for single aneurysms with small necks lying in an ideal position near the level of the dorsum sellae and pointing upward. It is necessary for those rare, very highly located, single aneurysms, and more frequently for treating additional aneurysms of the anterior circulation in one sitting. Much of the merit of an approach is a matter of surgical experience. It is well known that there are different levels of manual skills. We always attempted to make these operations simpler, faster, and to preserve normal anatomy by avoiding resection of brain or sacrifice of veins. In most instances, the subtemporal route has served our patients well. It is our experience and belief that the difference in endovascular and exovascular routes is that nature has created a simple route for endovascular surgery, whereas an artificial route has to be created to the base of the aneurysm in microneurosurgery. It is also our belief that a perfect clip at the base of the aneurysm more likely creates a permanent occlusion of the aneurysm than is possible with endovascular means. Quite frankly, if open cerebrovascular microsurgery is to survive, we have to be both good and efficient. Because of the rarity of these hidden and complex aneurysms, many cerebrovascular neurosurgeons, instead of improving their operative skills, stopped placing the perfect clip at the base of these posterior circulation aneurysms and handed these patients over to their endovascular colleagues. Further, in many centers, endovascular treatment has completely replaced open microsurgery for posterior circulation aneurysms, and even for anterior circulation aneurysms. Many neurosurgeons send patients to endovascular treatment, not to more experienced cerebrovascular surgeons, for many reasons, not the least of which is pressure from their surroundings. Much of the merit of any approach is a matter of surgical experience. We always attempt to make these operations simpler and faster, and to preserve normal anatomy by avoiding the destruction of the cranial base, brain, or veins. One of our secret weapons is good neuroanesthesia and avoiding brain compression. In this way, we still occlude the main part (> 80%) of posterior circulation aneurysms through open microsurgical means. The basilar bifurcation and its perforators are unforgiving for operative complications, but it did not prevent Drake and Peerless, and their students, from achieving excellent results in patients with these aneurysms. The authors were presented with the challenging case of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in a young patient secondary to a ruptured basilar apex aneurysm. The lesion has a favorable Hunt and Hess grade at the time of the patient’s admission, and imaging reveals a superiorly projecting aneurysm of moderate size (15 mm) with a wide neck. Bendok and associates and Hernesniemi and Korja present eloquent arguments for endovascular and open surgical treatment, respectively. Before the 1990s, open surgery was the only treatment option for this lesion. With the significant risk of rebleeding and the associated morbidity and mortality of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage from ruptured basilar apex aneurysms, neurosurgeons were driven to improve surgical techniques. Led by pioneers such as Charles Drake, approaches and techniques were devised to treat even very daunting lesions in this region. Even so, posterior circulation aneurysms, particularly those emanating from the basilar artery, are still associated with the highest surgical morbidity. The advent of endovascular therapy offered an alternative and exciting treatment option. Since the initial FDA approval in 1995, endovascular outcomes have steadily improved commensurate with rapid advances in the development and refinement of interventional tools and embolic material. Recent studies, including the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial and the Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial, have found decreased morbidity with the endovascular treatment of ruptured posterior circulation aneurysms compared with open microneurosurgery. As Bendok and colleagues note, the assessment of procedural risk (endovascular versus microsurgical) requires an evaluation of different aspects of the aneurysm’s morphology and anatomy. For any given aneurysm, the anticipated benefits and associated risks in the hands of the treating physician must be carefully weighed in selecting the appropriate treatment. Here, we discuss the microneurosurgical and endovascular treatment options, and conclude with our recommendation for this patient. Microneurosurgical treatment involves direct visualization to occlude the neck of the aneurysm. As Bendok and colleagues note, microneurosurgery has also undergone advances in the past several decades. Refined microneurosurgical technique, improvements in neuroanesthesia, and multimodality neurophysiological monitoring have contributed to improved surgical outcomes. Furthermore, despite ongoing improvements in endovascular therapy, long- term durability remains superior with surgical clipping. The key parameters to consider, arguably in decreasing order of importance, are the direction of the aneurysm’s dome, the anatomic relationship to the posterior clinoid process, and the width of the aneurysmal neck. The orientation of the dome of the aneurysm is a critical aspect in the decision to operate on a basilar apex aneurysm. Aneurysms that point anteriorly or superiorly may allow for better visualization of the posteriorly projecting perforating arteries arising from the proximal posterior cerebral arteries and the basilar artery, thereby facilitating dissection and subsequent clip placement. Posteriorly projecting aneurysms may obstruct the visualization of some of these critical perforating arteries, thereby increasing the risk of inadvertent perforator occlusion. The base of the aneurysm is situated at the level of the posterior clinoid process, and satisfactory exposure of the basilar artery for temporary occlusion will likely necessitate removal of the posterior clinoid when approaching the aneurysm through an orbitozygomatic approach. Although cranial-base cerebrovascular surgeons routinely remove the posterior clinoid process, it does increase the risk of surgical morbidity, and this risk should be factored into the decision. On the other hand, particularly high basilar bifurcations situated well above the posterior clinoid process can be difficult to reach and may sway the pendulum toward endovascular therapy if the anatomy is otherwise amenable. Finally, the width of the neck, although often discussed in the decision-making process for endovascular therapy, does have an impact on open surgical treatment as well. Indeed, narrow-necked aneurysms lend themselves toward both endovascular and open surgery. A wider neck means a longer distance to clear of perforators and to occlude with the surgical clip, which is made even more difficult by the small surgical corridors afforded by the approaches to this region. Fig. 15.5 The orbitozygomatic transsylvian approach provides a greater range of access to basilar apex aneurysms than afforded by the subtemporal approach, although the latter provides better access to the posterior aspect of the aneurysm’s dome where the perforators are the hardest to visualize. (Courtesy of Barrow Neurological Institute.)

Treatment of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms

Treatment of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms: Endovascular Treatment with Stent and Coil

Case Discussion

Microsurgical Clipping

Endovascular Treatment

Coiling Without an Assist Device

Balloon-Assisted Coiling with an Attempt at Complete Occlusion

Stent-Assisted Coiling

Flow Diversion

Coiling after Partial Clipping

Partial Balloon-Assisted Coiling Followed by Delayed Stent Coiling

Conclusion

Acknowledgment

Microsurgical Clipping of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms

Our Approach

Merits of the Subtemporal Approach

Discussion

Moderators

Treatment of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms

Surgical Occlusion

Treatment of Ruptured Wide-Neck Basilar Aneurysms

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree