Tumors of the Pituitary Gland

John Ausiello

Pamela U. Freda

Jeffrey N. Bruce

INTRODUCTION

Pituitary tumors are a common medical problem often found incidentally on routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These tumors are overwhelmingly benign but may cause symptoms due to mass effect, compression of the optic chiasm, excess hormonal secretion, or hypopituitarism. As such, the diagnosis and management of these tumors involves the coordinated efforts of neurosurgeons, endocrinologist, and ophthalmologists.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The true prevalence of pituitary adenomas is difficult to ascertain because most are asymptomatic; autopsy estimates of prevalence range from 1.7% to 24%. No sexual predilection exists, but the tumors are most common in adults, peaking in the third and fourth decades. Children and adolescents account for approximately 10% of cases. Pituitary tumors are not hereditary except for rare families with multiple endocrine neoplasia I (MEN-I), an autosomal dominant condition manifested by a high incidence of pituitary adenomas and tumors of other endocrine glands.

PATHOBIOLOGY

Pituitary tumors can be classified in four ways: by size, endocrine function, clinical findings, or histology. The first two remain the most common, as the majority of tumors are histologically benign and the clinical findings usually reflect the size or endocrinologic function of the tumor. With regard to size, microadenomas are less than 1 cm in diameter and macroadenomas are greater than 1 cm. Typically, when microadenomas cause symptoms, it is due to excess hormone secretion, whereas with macroadenomas, it is via compression of normal glandular or neural structures. Macroadenomas may invade the dura or bone and may infiltrate surrounding structures such as the cavernous sinus, cranial nerves, blood vessels, sphenoid bone, and sinus or brain. These locally invasive pituitary adenomas are nearly always histologically benign. In some studies, but not all, the proliferation index correlates with growth velocity and recurrence. However, their invasive character may be independent of their growth rate.

A second manner by which tumors can be classified is by the presence (or absence) of endocrine function, dividing tumors into secreting or nonsecreting tumors. Secreting tumors are less common and produce one or more anterior pituitary hormones, including prolactin (the most common secreting tumor), growth hormone (GH), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (causing Cushing disease), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), or luteinizing hormone (LH). Mixed secretory tumors account for 10% of adenomas; interestingly, these adenomas still have a monoclonal origin. Secretion of more than one hormone has implications for medical therapy, as all excess hormone secretion must be treated. Null cells, or nonsecreting adenomas, demonstrate no clinical or immunohistochemical evidence of hormone secretion.

In general, adenomas grow more slowly in older patients than younger patients. Pituitary carcinomas are rare but highly invasive, rapidly growing, and anaplastic. Unequivocal diagnosis relies on the presence of distant metastases, as certain histologic findings including pleomorphism and mitotic figures may be seen in benign adenomas.

The posterior pituitary, which contains the terminal processes of hypothalamic neurons and supporting glial cells, is a rare site of neoplasia. Infundibulomas are rare tumors of the neurohypophysis; they are variants of pilocytic astrocytomas. Granular cell tumors (e.g., myoblastomas or choristomas), also rare tumors of the neurohypophysis, are of uncertain origin.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

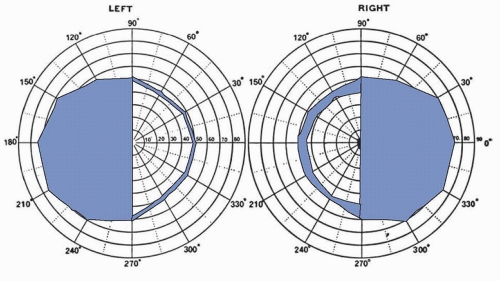

Clinical manifestations arise either from endocrine dysfunction or mass effect with invasion or compression of surrounding neural and vascular structures. The manifestations and management of hormonally active tumors are discussed in Chapter 117. Here, discussion is primarily limited to nonsecretory tumors, most of which are macroadenomas by the time they come to clinical attention. Macroadenomas may present with panhypopituitarism if the normal pituitary gland is destroyed. Headaches result from stretching of the diaphragma sellae and adjacent dural structures that transmit sensation through the first branch of the trigeminal nerve. Visual field abnormalities are caused by compression of the crossing fibers in the optic chiasm, first affecting the superior temporal quadrants and then the inferior temporal quadrants, leading to a bitemporal hemianopia. Further expansion compromises the noncrossing fibers and affects the lower nasal quadrants and finally the upper nasal quadrants (Fig. 100.1).

Visual loss may be accompanied by optic disc pallor and loss of central visual acuity although papilledema is rare. Patients usually complain of blurring or dimming of vision but often are unaware of peripheral visual loss. Formal visual field testing is important because some tumors affect only the macular fibers, causing central hemianopic scotomas that may be missed on routine screening. Bitemporal hemianopia is most common, but any pattern of visual loss is possible, including unilateral or homonymous hemianopia.

Lateral extension of the tumor with compression or invasion of the cavernous sinus may compromise third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerve functions, manifesting as diplopia. The third cranial nerve is most commonly affected. Numbness may occur in the V1 or V2 distribution. Overall, however, cranial nerve dysfunction is not a common feature of adenomas and may be more suggestive of other neoplasms of the cavernous sinus.

Adenomas can become quite large before causing symptoms. Suprasellar extension may compress the foramen of Monro, causing hydrocephalus and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Hypothalamic dysfunction could lead to diabetes insipidus but this condition is relatively rare. If diabetes insipidus is present, it is more suggestive of inflammation or possible tumor invasion of the pituitary stalk. Extensive subfrontal extension with compression of both

frontal lobes may cause personality changes or dementia. There may be seizures or motor and sensory dysfunction. Erosion of the skull base is a risk factor for the development of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea.

frontal lobes may cause personality changes or dementia. There may be seizures or motor and sensory dysfunction. Erosion of the skull base is a risk factor for the development of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea.

FIGURE 100.1 Pituitary macroadenoma. Bitemporal hemianopia; visual acuity OD (right eye) 15/200, OS (left eye) 15/30. The blind half-fields are black. (Courtesy of Dr. Max Chamlin.) |

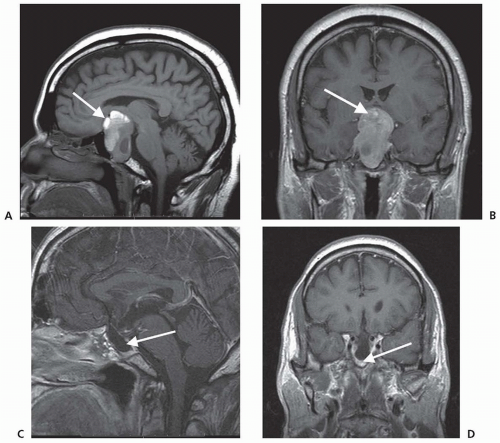

In about 5% of pituitary tumors, the first symptoms are those of pituitary apoplexy caused by hemorrhage or infarction of the adenoma. Symptoms include sudden onset of severe headache, oculomotor palsies, nausea, vomiting, altered mental state, diplopia, and rapidly progressive visual loss. Apoplexy is diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) or MRI and occasionally is an indication for emergency surgery (Fig. 100.2). Histologically, the adenoma shows massive necrosis and hemorrhage. Apoplexy is almost always caused

by a pituitary tumor, but it has been reported in other conditions, such as lymphocytic hypophysitis. Pituitary adenomas may enlarge during pregnancy, causing acute symptoms or even apoplexy.

by a pituitary tumor, but it has been reported in other conditions, such as lymphocytic hypophysitis. Pituitary adenomas may enlarge during pregnancy, causing acute symptoms or even apoplexy.

DIAGNOSIS

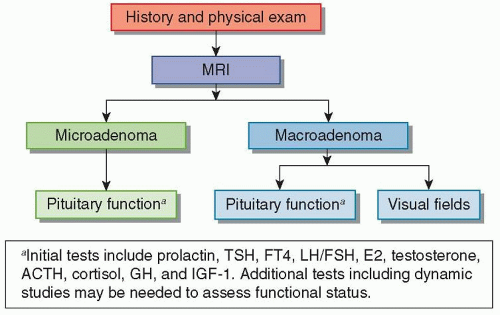

An algorithm for the initial assessment of a pituitary mass is shown in Figure 100.3.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

MRI is the best way to evaluate pituitary pathology because soft tissue is seen clearly without interference from the bony surroundings of the sella. MRI also produces images in any plane, which helps define the relationship of the tumor to the surrounding structures. Vascular structures such as the adjacent carotid artery are easily visualized by signal void. Normally, the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland has the same signal as white matter on T1-weighted imaging. With gadolinium, the normal gland enhances homogeneously. Small punctate areas of heterogeneity may be the result of local variations in vascularity, microcyst formation, or granularity within the gland. The posterior lobe shows increased signal on T1-weighted images, probably representing neurosecretory granules in the antidiuretic hormone (ADH)-containing axons.

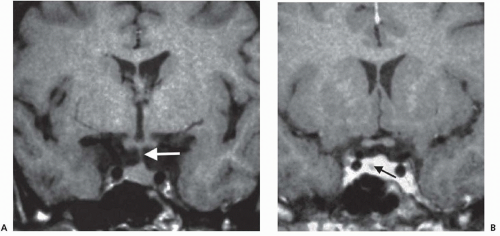

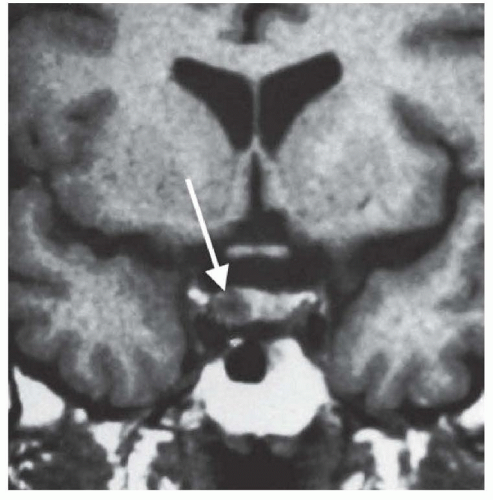

Microadenomas are sometimes difficult to see directly on MRI but may be inferred by glandular asymmetry, focal sellar erosion, asymmetric convexity of the upper margin of the gland, or displacement of the infundibulum (Fig. 100.4).

The normal gland usually shows more enhancement than a microadenoma (Fig. 100.5). In the presence of a macroadenoma, the normal gland may not be visualized and the bright signal of the posterior lobe may be absent. Areas of increased signal on the T1-weighted image may stem from hemorrhage; areas of low signal may represent cystic degeneration. MRI alone is usually sufficient, but CT may show the bony anatomy in better detail. MRI typically excludes an aneurysm, but magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or an angiogram is indicated if aneurysm is a serious diagnostic concern.

ACTH-secreting tumors may be too small to visualize on MRI. Diagnosis is suggested by the clinical features of Cushing disease, elevated 24-hour urinary free-cortisol levels, loss of ACTH suppression by high-dose as opposed to low-dose glucocorticoids, and elevated ACTH levels. However, the specific differentiation of an ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor from ectopic sources of ACTH may require measurement of ACTH peripherally and in each inferior petrosal sinus which drains the pituitary gland.

ENDOCRINE EVALUATION

Complete endocrine evaluation is necessary for all patients with pituitary tumors, not only to establish the diagnosis of a secreting adenoma but also to determine the presence of hypopituitarism (Tables 100.1 and 100.2), which may result from compression of the normal pituitary gland.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree