INTRODUCTION

During much of the 20th century, it was assumed that most dementia of the elderly was vascular in origin, an assumption challenged during the last few decades after the recognition and importance of Alzheimer-type pathologic changes. Nevertheless, with wider use of modern sophisticated neuroimaging techniques and accumulation of more knowledge on cerebral microinfarcts, interest in the role of vascular disease on cognitive decline reemerged and the clinical importance of vascular lesions in cognitive performance has been a new focus of attention lately.

Brain injury caused by stroke can undoubtedly contribute to dementia and intellectual impairment. Vascular dementia is a progressive cognitive dysfunction caused by stroke, often ischemic, but also hemorrhagic cerebrovascular disease as well as ischemic white matter disease or sequelae of hypotension or hypoxia.

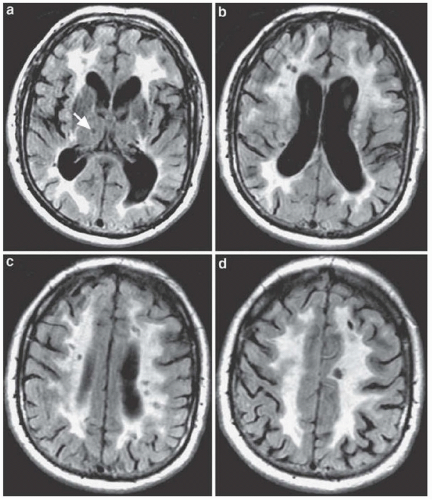

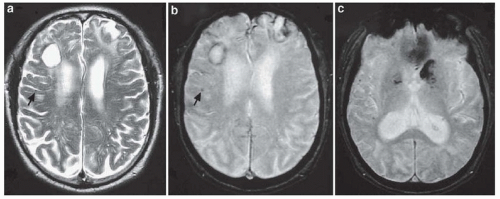

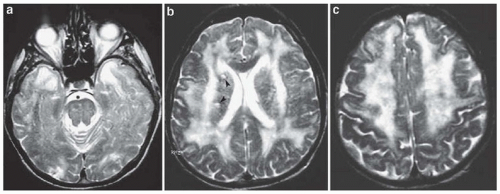

Diagnosis of vascular dementia has been controversial, and its definition has been unsettled despite numerous attempts at clarification. Unlike other neurodegenerative dementias, there are no specific pathologic criteria. Cerebrovascular disease is itself a heterogeneous disorder, with a variety of pathophysiologic mechanisms and clinical manifestations, and correspondingly, vascular dementia manifests also as a heterogeneous syndrome. Vascular dementia can result from a variety of mechanisms (

Table 53.1 and

Figs. 53.1,

53.2,

53.3).

There are many criteria for the clinical diagnosis of “vascular dementia,” some not adequately validated, many inconsistently applied and in general lacking satisfactorily high sensitivity and specificity. In terms of terminology, the concept of “vascular cognitive impairment” has been also recently proposed; a more general term referring to “cognitive impairment that is caused by or associated with vascular factors” and includes severity stages corresponding to either dementia or mild cognitive impairment.

Overall, as a practical rule, a diagnosis of vascular dementia requires (1) clinically (symptoms/signs) and radiologically ascertained strokes (see

Figs. 53.1,

53.2,

53.3), (2) dementia, and (3) a clear temporal relationship between stroke(s) and dementia.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

As many as 15% to 20% of patients with acute ischemic stroke older than age 60 years have dementia at the time of the stroke,

and 5% per year become demented thereafter. On a clinical basis, vascular dementia has been long considered as the second (after Alzheimer disease) or even the third (after Alzheimer and dementia with Lewy bodies) most frequent cause of dementia. Considering pathologic series data and related clinical-pathologic correlations makes the issue quite more complex.

Although the vast majority of elderly demented patients have Alzheimer-type pathologic changes (70% to 80%), approximately half of them have coexisting cerebrovascular infarctions too, whereas only about 30% have “pure” Alzheimer only pathology. Therefore, the majority of demented subjects have mixed Alzheimer and vascular pathologic changes. Adding to the argument of higher contribution rates of vascular dementia is the fact that most pathologic studies consider only larger infarcts, whereas microinfarcts (if time and resources permit their identification) are extremely common and diffuse in the brain. Finally, many white matter abnormalities visualized on brain magnetic resonance imaging are often undetectable by

standard neuropathologic examinations performed on autopsy, suggesting limited sensitivity of neuropathology for detection of cerebrovascular damage.

On the counterargument, the clinical salience of such microinfarcts on cognitive function has not been convincingly demonstrated. Additionally, dementia due to infarcts solely without significant pathologic contributions of the Alzheimer or Lewy body type (i.e., pure vascular dementia) is strikingly uncommon with estimated rates between 2% and 10% of dementias (not more than 5% of dementias in the United States).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access