Chapter 11 Agnosias

Visual Agnosias

Cortical Visual Disturbances

Patients with bilateral occipital lobe damage may have complete “cortical” blindness. Some patients with cortical blindness are unaware that they cannot see, and some even confabulate visual descriptions or blame their poor vision on dim lighting or not having their glasses (Anton syndrome, originally described in 1899). Patients with Anton syndrome may describe objects they “see” in the room around them but walk immediately into the wall. The phenomena of this syndrome suggest that the thinking and speaking areas of the brain are not consciously aware of the lack of input from visual centers. Anton syndrome can still be thought of as a perceptual deficit rather than a visual agnosia, but one in which there is unawareness or neglect of the sensory deficit. Such visual unawareness is also frequently seen with hemianopic visual field defects (e.g., in patients with R hemisphere strokes), and it even has a correlate in normal people; we are not conscious of a visual field defect behind our heads, yet we know to turn when we hear a noise from behind. In contrast to Anton syndrome, some cortically blind patients actually have preserved ability to react to visual stimuli, despite the lack of any conscious visual perception, a phenomenon termed blindsight or inverse Anton syndrome (Ro and Rafal, 2006). Blindsight may be considered an agnosic deficit, because the patient fails to recognize what he or she sees. Residual vision is usually absent in blindness caused by disorders of the eyes, optic nerves, or optic tracts. Patients with cortical vision loss may react to more elementary visual stimuli such as brightness, size, and movement, whereas they cannot perceive finer attributes such as shape, color, and depth. Subjects sometimes look toward objects they cannot consciously see. One study reported a woman with postanoxic cortical blindness who could catch a ball without awareness of seeing it. Blindsight may be mediated by subcortical connections such as those from the optic tracts to the midbrain.

Lesions causing cortical blindness may also be accompanied by visual hallucinations. Irritative lesions of the visual cortex produce unformed hallucinations of lines or spots, whereas those of the temporal lobes produce formed visual images. Visual hallucinations in blindness are referred to as Bonnet syndrome (Teunisse et al., 1996). Although Bonnet originally described this phenomenon in his grandfather, who had ocular blindness, complex visual hallucinations occur more typically with cortical visual loss (Manford and Andermann, 1998). Visual hallucinations can occur during recovery from cortical blindness; positron emission tomography (PET) has shown metabolic activation in the parieto-occipital cortex associated with hallucinations, suggesting hyperexcitability of the recovering visual cortex (Wunderlich et al., 2000).

In practice, we diagnose cortical blindness by the absence of ocular pathology, the preservation of the pupillary light reflexes, and the presence of associated neurological symptoms and signs. In addition to blindness, patients with bilateral posterior hemisphere lesions are often confused, agitated, and have short-term memory loss. Amnesia is especially common in patients with bilateral strokes within the posterior cerebral artery territory, which involves not only the occipital lobe but also the hippocampi and related structures of the medial temporal region. Cortical blindness occurs as a transient phenomenon after traumatic brain injury, in migraine, in epileptic seizures, and as a complication of iodinated contrast procedures such as arteriography. Cortical blindness can develop in the setting of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (Wunderlich et al., 2000), meningitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, dementing conditions such as the Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, or the posterior cortical atrophy syndrome described in Alzheimer disease and other dementias (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006).

Balint Syndrome and Simultanagnosia

In 1909, Balint described a syndrome in which patients act blind, yet can describe small details of objects in central vision (Rizzo and Vecera, 2002). The disorder is usually associated with bilateral hemisphere lesions, often involving the parietal and frontal lobes. Balint syndrome involves a triad of deficits: (1) psychic paralysis of gaze, also called ocular motor apraxia, or difficulty directing the eyes away from central fixation; (2) optic ataxia, or incoordination of extremity movement under visual control (with normal coordination under proprioceptive control; and (3) impaired visual attention. These deficits result in the perception of only small details of a visual scene, with loss of the ability to scan and perceive the “big picture.” Patients with Balint syndrome literally cannot see the forest for the trees. Some but not all patients have bilateral visual field deficits. In bedside neurological examination, helpful tests include asking the patient to interpret a complex drawing or photograph, such as the “Cookie Theft” picture from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Partial deficits related to Balint syndrome have also been described, including isolated optic ataxia, or impaired visually guided reaching toward an object. Optic ataxia likely results from disruption of the transmission of visual information for visual direction of motor acts from the occipital cortex to the premotor areas. This function involves portions of the dorsal occipital and parietal areas as part of the “dorsal visual stream” (Himmelbach et al., 2009). A second partial Balint syndrome deficit is simultanagnosia, or loss of ability to perceive more than one item at a time, first described by Wolpert in 1924. The patient sees details of pictures, but not the whole. Many such patients have left occipital lesions and associated pure alexia without agraphia; these patients can often read “letter-by-letter,” or one letter at a time, but they cannot recognize a word at a glance (see Chapter 12). Robertson and colleagues (1997) emphasized deficient spatial organization as a contributing factor to the perceptual difficulties of a patient with Balint syndrome secondary to bilateral parieto-occipital strokes. Balint syndrome has also been reported in patients with posterior cortical atrophy and related neurodegenerative conditions involving the posterior parts of both hemispheres (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006; McMonagle et al., 2006).

Visual Object Agnosia

Visual object agnosia is the quintessential visual agnosia: the patient fails to recognize objects by sight, with preserved ability to recognize them through touch or hearing in the absence of impaired primary visual perception or dementia (Biran and Coslett, 2003). In 1890, Lissauer distinguished two subtypes of visual object agnosia: apperceptive visual object agnosia, referring to the synthesis of elementary perceptual elements into a unified image, and associative visual object agnosia, in which the meaning of a perceived stimulus is appreciated by recall of previous visual experiences.

Apperceptive Visual Agnosia

The first type, apperceptive visual agnosia, is difficult to separate from impaired perception or partial cortical blindness. Patients with apperceptive visual agnosia can pick out features of an object correctly (e.g., lines, angles, colors, movement), but they fail to appreciate the whole object (Grossman et al., 1997).Warrington and Rudge (1995) pointed to the right parietal cortex for its importance in visual processing of objects, and they found this area critical to apperceptive visual agnosia. A patient described by Luria misnamed eyeglasses as a bicycle, pointing to the two circles and a crossbar. Another study considered apperceptive visual agnosia related to bilateral occipital lesions a “pseudoagnosic syndrome” associated with visual processing defects, as compared to true visual agnosias, in which the right parietal cortex is deficient in identifying and recognizing visual objects. Recent evidence of the functions of specific cortical areas has included the specialization of the medial occipital cortex for appreciation of color and texture, whereas the lateral occipital cortex is more involved with shape perception. Deficits in these specific visual functions can be seen in patients with visual object agnosia (Cavina-Pratesi et al., 2010). On the other hand, a patient reported by Karnath et al. (2009) had visual form agnosia with bilateral medial occipitotemporal lesions.

Another way of analyzing apperceptive visual agnosia is by the focusing of visual attention. Theiss and DeBleser in 1992 distinguished two features of visual attention: a wide-angle attentional lens that sees the figure generally but perceives only gross features (the forest), and a narrow-angle spotlight that focuses on the fine visual details (the trees). They described a patient with a faulty wide-angle attentional beam; she could identify small objects within a drawing but missed what the drawing represented. Fink and colleagues (1996), in PET studies of visual perception in normal subjects, found that right hemisphere sites, particularly the lingual gyrus, activated during global processing of figures, whereas left hemisphere sites, particularly the left inferior occipital cortex, activated during more local processing. The ability of patients with apperceptive visual agnosia to perceive fine details but not the whole picture (missing the forest for the trees) is closely related to Balint syndrome and simultanagnosia.

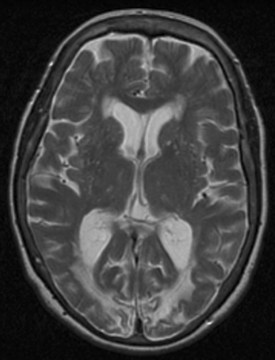

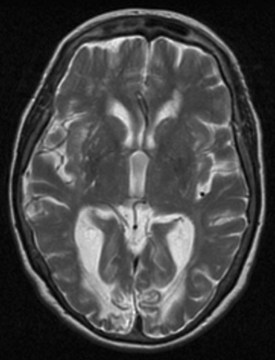

As with most cortical visual syndromes, apperceptive visual agnosia usually occurs in patients with bilateral occipital lesions. It may represent a stage in recovery from complete cortical blindness. Deficits in recognition of visual objects may be especially apparent with recognition of degraded images, such as drawings rather than actual objects. Apperceptive visual agnosia can also be part of dementing syndromes (Kirshner and Lavin, 2006; McMonagle et al., 2006) (Fig. 11.1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree