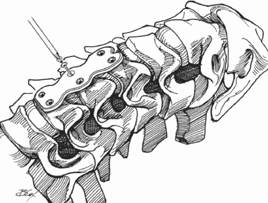

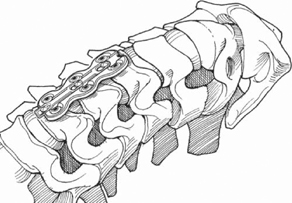

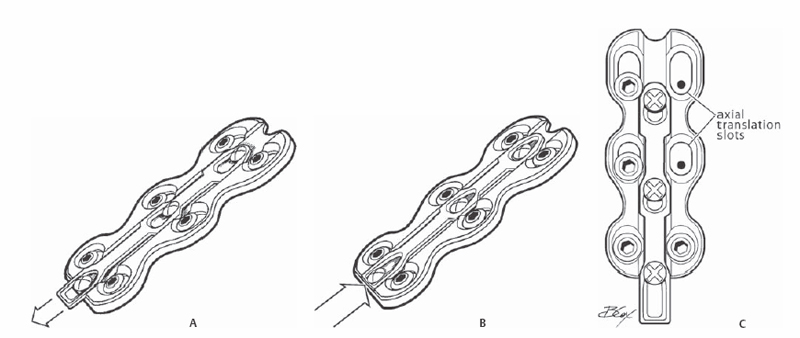

23 Wade K. Jensen and Paul A. Anderson Anterior cervical plating provides stabilization of the cervical spine after arthrodesis. Theoretical advantages of plate fixation include improved initial stability, decreased complications from bone graft dislocation, end-plate fracture, and late kyphotic collapse. Whether anterior cervical plates result in higher fusion success is controversial, although recent reports confirm the efficacy of one- and two-level fusions. Modern plates have the capacity of screw capture, thereby preventing loosening, and require only unilateral screw purchase. Plate systems can be static or dynamic. Static plates have a rigid connection between screw and plate and do not allow motion during healing. Dynamic plates allow change in plate position to accommodate changes in the interbody graft that occurs following implantation. During healing of interbody cervical fusions graft, resorption of 1 to 2 mm per interspace occurs. Theoretically, plates may unload the graft or shield it from stress, and may lead to nonunion or plate failure. This is seen more commonly in longer fusion. Cervical spine plates are classified as follows: (1) unrestricted backout, and (2) constrained (static) and semiconstrained plates that include two subclasses of (a) rotational and (b) translational. Unrestricted backout plates are of historical note. These were nonlocked, required bicortical screw purchase, and were associated with screw backout. They are therefore not currently recommended. The constrained or static plates are locked screw interface that allow unicortical fixation without screw backout (Fig. 23.1). Dynamic or semiconstrained plates have been developed that allow axial settling to accommodate a potential biologic or mechanical shortening of the anterior strut graft (Fig. 23.2). Rotational plates allow rotation or toggle at the plate-screw interface. The translational plates offer locked bone-screw interfaces with the ability to translate along the long axis to accommodate shortening (Fig. 23.3). Several mechanisms are available including plates that have oval holes allowing translation through the holes, whereas others have screws fixed to the plate and translation occurs by plate shortening. Fig. 23.1 Placement of a statically locked plate. Fig. 23.2 Placement of a dynamic plate, allowing translation. Fig. 23.3(A-C) Examples of translation along the long axis to accommodate shortening. Anterior cervical plates are load-sharing devices that require a graft or other interbody device. Cadaveric biomechanical load transmissions through the graft were found to be higher with a dynamic (68–80%) versus static plate (53–57%). This was accentuated when the graft was undersized (dynamic 50–57% versus static 17%). Therefore, one may hypothesize that a dynamic plate will lead to high union rates when the graft is appropriately loaded. The lack of load sharing over time in static plates may lead to hardware fatigue or loosening. Still unknown, however, is the critical amount of load sharing to allow bony union. What is known is that strain rates of less than 5 to 6% lead to union, and strain rates of >10% lead to nonunion. Thus, plate fixation must limit strain and optimize load sharing to allow healing. Anterior cervical plates result in high fusion rates, prevent graft collapse, and maintain spinal alignment. A low rate of hardware-related complications should occur. Anterior cervical plate fixation has a wide range of indications. It is used to stabilize unstable conditions from trauma or other destructive lesions such as tumors. Its most common use is following decompression for degenerative conditions. It is thought to result in higher fusion success for two- and three-level cases. Its use following single-level fusion is controversial. Although evidence of efficacy in fusion success is conflicting, several investigations have demonstrated that plating for single-level cases results in a lower incidence of graft complication and maintains lordosis to a greater degree than do nonplated cases. Anterior plates can be used after both diskectomy and corpectomy. Adequate evidence is not available to determine the role of dynamic versus static plates. Longer constructs such as three- or four-level fusions appear to have a high failure rate with static plates, with the usual failure mechanism being screw loosening at the caudal end and graft dislodgment or intussusception. In these cases, if an anterior plate is used, the authors recommend a translation plate. Static plates have a relative contraindication for use in long multilevel reconstructions secondary to early failure. Dynamic plating has been shown biomechanically to be weaker in trauma patients with significant posterior involvement. A recent study suggests that dynamic plates were stable until the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) was sacrificed, which then resulted in significantly more range of motion (ROM) in flexion and extension, and more axial ROM. Clinically it is unknown if this is an important effect. In a randomized study of patients with combined anterior and posterior injury, anterior static plates resulted in similar outcomes compared with posterior cervical plates. The efficacy of translational plates in these patients is unknown. Anterior plates should be used with caution in patients with osteoporosis, renal osteodystrophy, or severe kyphotic deformities, or in patients in a highly unstable condition with total ligamentous destruction, severe comminution, or missing posterior elements. If patients have osteoporosis or rheumatoid arthritis that compromises fixation, one may consider either supplemental posterior fixations or more rigid immobilization postoperatively with close radiographic follow-up. Anterior diskectomy and fusion is performed with the patient in the supine position on a standard table. The head is held with a horseshoe head holder, with the neck slightly extended. A shoulder roll can be placed either transversely or longitudinally, based on surgeon preference, to aid in neck extension. Three-inch cloth tape is used to lower the patient’s shoulders bilaterally. The endotracheal tube should be taped on the right side of the mouth. Verify that once positioned, the patient is symmetric before sterile preparation and draping. In trauma patients, reduction should be performed prior to plating. Plates should be placed in the midline and have screws as close to the fused disk space as possible. Lateral placement can result in vertebral artery injury or intraforaminal screw placement. The plate should lie as flush as possible on the spine. This often requires machining of the osteophytes or bony prominences. Plate length should be chosen to keep the plate 5 mm or more away from the adjacent level to avoid adjacent level ossification. Screws orientation should be parallel to the end plates to avoid crossing an unfused disk. To keep the plate oriented to the midline, the plate should be firmly held in place. If the surgeon is not sure of the position, an anteroposterior radiograph should be obtained. Most systems have temporary fixation pins that can maintain orientation while drilling and screw placement. If the patient is small, particularly small Asian women, sometimes even the smallest screws in the set are too long, so shorter screws need to be available. To avoid iatrogenic spinal cord injury, make sure that when drilling any pilot hole to check the length of the drill bit protruding from the drill guide. Dysphagia is a common complication after anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion (ACDF) with plate fixation. A recent study has shown that to minimize dysphagia, osteophytes should be removed that would prevent the plate from sitting flat against bone. Low-profile plates have been shown to minimize dysphagia postoperatively. Once decompression is completed and the graft is properly placed, then plate placement is performed. Good carpentry of the graft-host interface is paramount for stability. The anterior osteophytes are burred down to allow a flat surface for the plate to sit. The plate size should be carefully chosen so the screws are placed adjacent to the end plates nearest the diskectomy/corpectomy. Lower profile plates have a lower incidence of dysphagia and should be used if possible. Screw length can be gauged from the vertebral body depth determined when the graft was fashioned, commonly 14 mm. Verify that the drill protruding from the drill guide is 14 mm prior to drilling to avoid catastrophic complications. If placing bicortical screws, use fluoroscopy to verify drilling and screw placement. Hold the plate in the midline while drilling so the plate does not shift. Eccentric plate placement can result in vertebral artery injury or screw placement that is intraforaminal. Lastly, obtain intraoperative radiographs to verify position of the plate prior to closure. Immobilization is controversial and depends on the injury, procedure performed, and fixation obtained intraoperatively. If screws have poor purchase, larger diameter or longer screws can be placed. Another option is bicortical screw placement. Alternatively, posterior fixation can augment the anterior plate. If hardware is loose or screws are seen to be backing out, early revision is recommended.

Anterior Cervical Plating: Static and Dynamic

Description

Key Principles

Expectations

Indications

Contraindications

Special Considerations

Special Instructions, Position, and Anesthesia

Tips, Pearls, and Lessons Learned

Difficulties Encountered

Key Procedural Steps

Bailout, Rescue, Salvage Procedures

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree