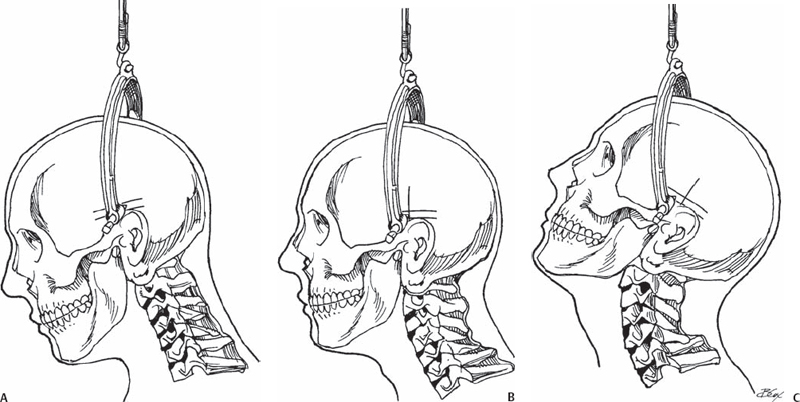

73 Gianluca Vadalà, Alexander R. Vaccaro, and Joon Yung Lee The graduated weighted reduction technique is commonly used for both traumatic and nontraumatic fractures and dislocation of the cervical spine. When performed under close supervision of an experienced surgeon, this is a safe and reliable method to achieve anatomic realignment. The anatomic abnormality is identified through use of various imaging modalities. Frequently, a lateral cervical spine x-ray is the quickest and most helpful screening modality to identify cervical malalignment. If a unilateral or bilateral facet dislocation of the cervical spine is identified, weighted-reduction techniques can be used to efficiently realign the spinal column and provide temporary stabilization. Computed tomography (CT) is also useful in identifying anatomic abnormalities in those cases where plain radiographs are inadequate or unrevealing. In the setting of a traumatic cervical dislocation, obtaining a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study prior to reduction is controversial. Some advocate obtaining MRI to confirm the presence or absence of a herniated disk at the site of dislocation to prevent further spinal cord damage during the reduction method. Others argue that as long as the patient is awake and alert, weighted reduction can be performed safely. If a herniated disk is identified anterior to the spinal cord prior to reduction, many surgeons proceed with an anterior decompression and stabilization procedure without performing a presurgical closed reduction. Once the type of displacement is identified, the axis of traction needs to be determined. Frequently, in cases of unilateral or bilateral facet dislocations, the traction should be applied in the axis of flexion. It is not unusual to apply 30 to 45 degrees of flexion moment on the head through traction to begin the process of realigning the spine. In cases of displaced odontoid fractures, bi-vector traction is often useful to obtain an efficient reduction. This technique combines both a longitudinal and flexion vector force to obtain a satisfactory realignment. In patients with basilar invagination in the setting of rheumatoid arthritis, longitudinal low-weight traction (10 to 20 lb) often suffices. Particular care must be taken in extension-type injuries. Frequently, injuries with extension mechanism are extremely unstable, and even a small degree of weight may result in excessive interspace distraction. In general, only a gentle graded flexion vector is used in extension-type injuries, or patients may be reduced in a halo vest with manual halo ring flexion. The goal of the weighted traction reduction is to restore and maintain normal spinal alignment of the displaced cervical spine, providing temporary stabilization and indirect decompression of the spinal cord. This potentially allows for improved neurologic recovery and prevention of further neurologic injury. Traction is often a temporary measure, until more definitive management (usually surgical stabilization) is performed. The most common indications for closed traction reduction of the cervical spine are unilateral or bilateral dislocated facets. In these settings, higher weights on the order of 30 to 120 lb are frequently required to obtain a reduction. Lower weight traction (10 to 30 lb) is often used in the setting of displaced odontoid fractures, traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis, rotatory atlantoaxial subluxation, basilar invagination, and cranial settling. Traction may also be used efficiently in other nontraumatic cervical spine conditions that result in instability or deformity such as tumor, infections, rheumatoid arthritis, and late posttraumatic kyphotic deformity or instability. Longitudinal traction in extension distraction injuries, and in patients who are not alert and cannot participate in their neurologic examination. Physicians involved in the treatment of cervical spine injuries must be aware of the possibility of multiple noncontiguous levels of spinal injury before attempting reduction of any cervical fracture or dislocation. Following a successful or failed closed reduction and prior to an open reduction or in situ fusion procedure, MRI evaluation for the presence of a disk herniation or other space-occupying lesion should be done to determine the type of necessary surgical approach. Cranial tongs, head-halters, or halo rings can be used to hold weights for traction. We prefer the use of stainless-steel Gardner-Wells cranial tongs. The others have weight restrictions that are far less than what is sometimes necessary to achieve satisfactory reduction. The position of the placement of the cranial tongs is crucial (Fig. 73.1). The pins are applied below the equator of the skull, approximately 1 cm superior of the pinna of the outer ear. Direct axial traction is applied with the tongs placed longitudinally in line with the external auditory meatus. Placement of the tongs more anteriorly or posteriorly applies an extension or flexion moment to the cervical spine, respectively.

Closed Cervical Traction Reduction Techniques

Description

Key Principles

Expectations

Indications

Contraindications

Special Considerations

Key Procedural Steps

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree