Chapter 27 Hypotonic (Floppy) Infant

Floppy, or hypotonic, infant is a common scenario encountered in the clinical practice of child neurology. It can present significant challenges in terms of localization and is associated with an extensive differential diagnosis (Box 27.1). As with any clinical problem in neurology, attention to certain key aspects of the history and examination allows correct localization within the neuraxis and narrows the list of possible diagnoses. Further narrowing of the differential is achievable with selected testing based on the aforementioned findings. Understanding the anatomical and etiological aspects of hypotonia in infancy necessarily begins with an understanding of the concept of tone. Tone is the resistance of muscle to stretch. Categorization of tone differs among authors, but assessment is performed with the patient at rest and all parts of the body fully supported; examination involves tonic or phasic stretching of a muscle or the effect of gravity. Tone is an involuntary function and therefore separate and distinct from strength or power, which is the maximum force generated by voluntary contraction of a muscle. Function at every level of the neuraxis influences tone, and disease processes affecting any level of the neuraxis may reduce tone. Although a comprehensive review of conditions associated with hypotonia in infancy is beyond the scope of a single chapter, this chapter considers the basic approach to evaluating the floppy infant and considers several key disorders.

Box 27.1 Differential Diagnosis of the Floppy Infant

Approach to Diagnosis

History

Several features of the history may point to a specific diagnosis or category of diagnoses leading to hypotonia, or may permit distinguishing disorders present during fetal development from disorders acquired during the perinatal period. Thoroughly investigate a family history of disorders known to be associated with neonatal hypotonia, especially in the mother or in older siblings. Certain dominantly inherited genetic disorders (e.g., myotonic dystrophy) are associated with anticipation (earlier or more severe expression of a disease in successive generations). Such disorders may be milder and therefore undiagnosed in the mother. A maternal history of spontaneous abortion, fetal demise, or other offspring who died in infancy may also provide clues to possible diagnoses. A history of reduced fetal movement is a common feature of disorders associated with hypotonia, and may indicate a peripheral cause (Vasta et al., 2005). A history of maternal fever late in pregnancy suggests in utero infection, while a history of a long and difficult delivery followed by perinatal distress suggests hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy with or without accompanying myelopathy. Among the many potential causes of neonatal hypotonia, acquired perinatal injury is far more common than inherited disorders and is rarely overlooked. However, also consider the possibility of a motor unit disorder leading to perinatal distress and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Physical Examination

General Features of Hypotonia

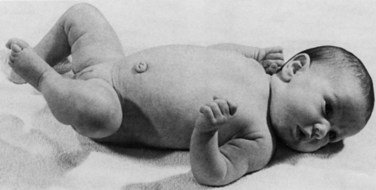

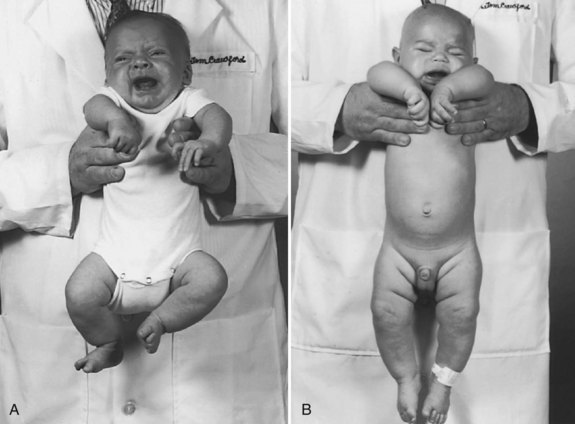

Assessing tone in an infant involves both observation of the patient at rest and application of certain examination maneuvers designed to evaluate both axial and appendicular musculature. Beginning with observation, a normal infant lying supine on an examination table will demonstrate flexion of the hips and knees so that the lower extremities are clear of the examination table, flexion of the upper extremities at the elbows, and internal rotation at the shoulders (Fig. 27.1). A hypotonic infant lies with the lower extremities in external rotation, the lateral aspects of the thighs and knees touching the examination table, and the upper extremities either extended down by the sides of the trunk or abducted with slight flexion at the elbows, also lying against the examination table. Evaluation of the traction response is done with the infant in supine position; the hands are grasped and the infant pulled toward a sitting position. A normal response includes flexion at the elbows, knees, and ankles, and movement of the head in line with the trunk after no more than a brief head lag. The head should then remain erect in the midline for at least a few seconds. An infant with axial hypotonia demonstrates excessive head lag with this maneuver (Fig. 27.2), and once upright, the head may continue to lag or may fall forward relatively quickly. Absence of flexion of the limbs may also be seen and indicates either appendicular hypotonia or weakness. The traction response is normally present after 33 weeks postconceptional age. Vertical suspension is performed by placing hands under the infant’s axillae and lifting the infant without grasping the thorax. A normal infant has enough power in the shoulder muscles to remain suspended without falling through, with the head upright in the midline and the hips and knees flexed (Fig. 27.3, A). In contrast, a hypotonic infant held in this manner slips through the examiner’s hands, often with the head falling forward and the legs extended at the knees (see Fig. 27.3, B). Infants with axial hypotonia related to brain injury may also demonstrate crossing, or scissoring, of the legs in this position, which is an early manifestation of appendicular hypertonia. In horizontal suspension, the infant is held prone with the abdomen and chest against the palm of the examiner’s hand. A normal infant maintains the head above horizontal with the limbs flexed, while a hypotonic infant drapes over the examiner’s hand with the head and limbs hanging limply. Other examination findings in hypotonic infants include various deformities of the cranium, face, limbs, and thorax. Infants with reduced tone may develop occipital flattening, or positional plagiocephaly, as the result of prolonged periods of lying supine and motionless.

Localization

The key features of disorders of cerebral function, particularly the cerebral cortex, are encephalopathy and seizures. Encephalopathy manifesting as decreased level of consciousness may be difficult to ascertain, given the large proportion of time normal infants spend sleeping. However, full-term or near-term infants with normal brain function spend at least some portion of the day awake with eyes open, particularly with feeding. Encephalopathy also manifests with excessive irritability or poor feeding, although the latter problem is rarely the sole feature of cerebral hemispheric dysfunction and may occur with disorders at more distal sites. Infants with centrally mediated hypotonia of many different etiologies frequently have relatively normal power despite a hypotonic appearance. Power may not be observable under normal circumstances because of a paucity of spontaneous movement, but it may be observable with application of a noxious stimulus such as a blood draw or placement of a peripheral intravenous catheter. Other indicators of central rather than peripheral dysfunction include fisting (trapping of the thumbs in closed hands), normal or brisk tendon reflexes, and normal or exaggerated primitive reflexes. Tendon reflexes should be tested with the infant’s head in the midline and the limbs symmetrically positioned; deviations from this technique often result in spuriously asymmetrical reflexes. Primitive reflexes are involuntary responses to certain stimuli that normally appear in late fetal development and are supplanted within the first few months of life by voluntary movements. Abnormalities of these reflexes include absent or asymmetrical responses, obligatory responses (persistence of the reflex with continued application of the stimulus), or persistence of the reflexes beyond the normal age range. Two of the most sensitive primitive reflexes are the Moro and asymmetrical tonic neck reflexes. The Moro reflex is a startle response present from 28 weeks after conception to 6 months postnatal age (Gingold et al., 1998). Quickly dropping the infant’s head below the level of the body while holding the infant supine with the head supported in one hand and the body supported in the other readily elicits this reflex. The normal response consists of initial abduction and extension of the arms with opening of the hands, followed quickly by adduction and flexion with closure of the hands. The tonic neck reflex is a vestibular response and is present from term until approximately 3 months of age. The response is elicited by rotating the head to one side while the infant is lying supine. The normal response is extension of the ipsilateral limbs while the contralateral limbs remain flexed. Central disorders resulting in hypotonia may also be associated with dysmorphism of the face or limbs, or malformations of other organs. Various defects in O-linked glycosylation of α-dystroglycan, a protein associated with the dystrophin glycoprotein complex that stabilizes the sarcolemma, result in structural defects of the brain, eye, and skeletal muscle.

Diagnostic Studies

Neuroimaging

Neuroimaging studies, in particular magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are most useful when suspecting structural abnormalities of the CNS. T1-weighted images most readily detect congenital malformations of the brain and spinal cord, while T2-weighted images and various T2-based sequences reveal abnormalities of white matter and show evidence of ischemic injury. Specialized techniques such as MR spectroscopy may show evidence of mitochondrial disease (Matthews et al., 1993) or disorders of cerebral creatine metabolism (Frahm et al., 1994). When performing neuroimaging studies that require sedation on hypotonic infants, give particular consideration to airway management and other safety issues.

Nerve Conduction Studies and Electromyography

Nerve conduction studies and EMG are the studies of choice in a suspected motor unit disorder when other available clinical information does not suggest a specific diagnosis. The two techniques are complementary and always performed together. They allow distinction between primary disorders of muscle and peripheral nerve disorders when the two are indistinguishable on clinical grounds. Repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) studies evaluate the integrity of the neuromuscular junction, abnormalities of which are not detectable with routine nerve conduction studies or EMG. The most commonly observed abnormality on low-rate (2-3 Hz) RNS studies of patients with various forms of myasthenia is a significant decrement, usually defined as 10% or greater, in the amplitude of the compound motor action potential (CMAP) between the first and fourth or fifth stimuli of a series. Single fiber EMG (SFEMG) is a highly specialized technique that evaluates the delay in depolarization between adjacent muscle fibers within a single motor unit, referred to as jitter. This modality is highly sensitive for neuromuscular junction abnormalities but has a low specificity and requires a cooperative patient. SFEMG with stimulation of the appropriate nerve has been described in pediatric patients (Tidwell and Pitt, 2007), but experience with this technique in infants is limited to a small number of centers. The utility of these neurophysiology studies is dependent on the skill and experience of the clinician performing the tests, as well as the precision of the question posed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree